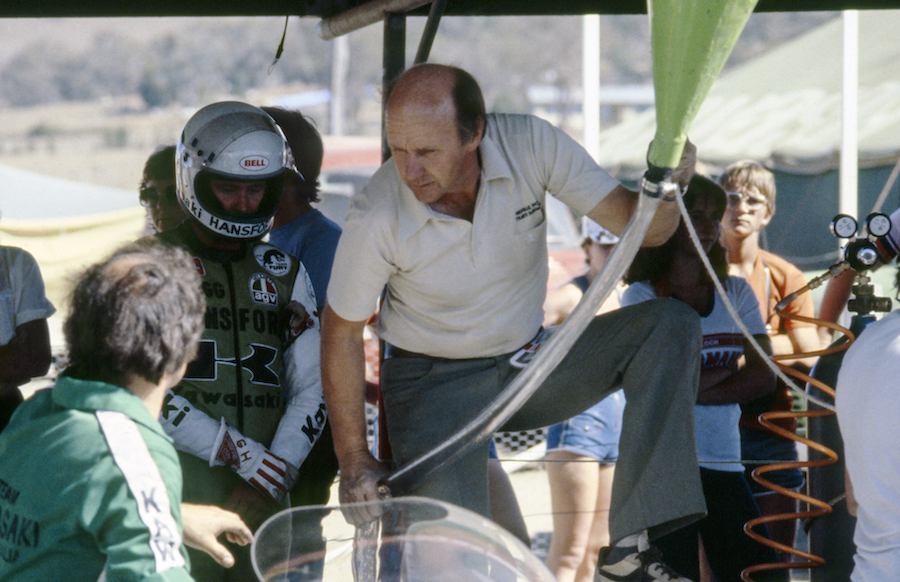

At the end of an Easter weekend, three riders share a joke (right) while friends and family look on. This photograph, taken after the Unlimited Australian Grand Prix at Bathurst in 1974, sums up all that was great about Mount Panorama. It’s also a snapshot of the moment when motorcycle racing changed forever in Australia, as a new international professionalism swept the sport.

The man in the green Kawasaki leathers is Ron Toombs. Aged 40 and known as the Master of Mount Panorama, he had won more than 15 GP titles on Australia’s most challenging circuit. Five years later he would die there in a crash that rocked Australian motorcycling to its core.

On the left in the red leathers is Warren Willing, and the other youngster, at far right, with the long blond hair and yellow leathers is Gregg Hansford.

Toombs had battled all weekend with Willing and Hansford, who were barely half his age and had only been racing for a couple of years. In their last race of the weekend, Willing had narrowly beaten Hansford to the line, with Toombs third. As well as being a spectacular race, it was a generational change in the sport locally.

Willing has a Chesterfield sash around his shoulders and a fat cheque for $1000 from the cigarette sponsor coming his way. That would cover nearly a third of the cost of his Yamaha TZ700.

But are the two young guns lording their victory over the old master? No way. There is a reverence here you seldom see on the podium these days.

Look into the background of this image and you see a crowd sharing a special moment in the golden sunlight of a late afternoon autumn day with the famous Mountain behind them.

Most circuits lose their soul when the racing ends, but Bathurst was never like that. There was a unique bond between riders and spectators in a classic Aussie bush setting.

Mount Panorama was at its peak from the mid-1970s to the early 80s. Its annual Easter races were a pilgrimage for older riders and a rite of passage for youngsters. It was the same for the fans. You hadn’t lived unless you made at least one trip there on your motorcycle, with all your camping gear lashed to the pillion seat.

High on the Mountain, you’d set up a base for the four days with your mates. The chilly nights were usually followed by an early morning fog that settled in the valleys below. The campers were therefore above the clouds, which made for a slightly surreal experience.

As the fog was burnt off by the sun, the sound of racing engines brought bleary-eyed campers to the wire fences just above the track.

The sheer pace was breathtaking. The bikes and sidecars seemed to do impossible speeds just metres below the spectators.

Not only that, they were heading for a series of blind corners that got tighter and tighter, close to the edge, eventually funnelling the pack out onto Conrod Straight.

This was the fastest circuit in Australia and, being part road and part dedicated racetrack, a unique challenge to the riders.

To recapture the spirit of these times we bring you some snapshots of the 70s at Mount Panorama. Next issue we go deep into the 80s.

Prototype or Production?

One of Bathurst’s greatest mysteries came about from the epic victory by an injured Ken Blake in the 1975 Unlimited Production race.

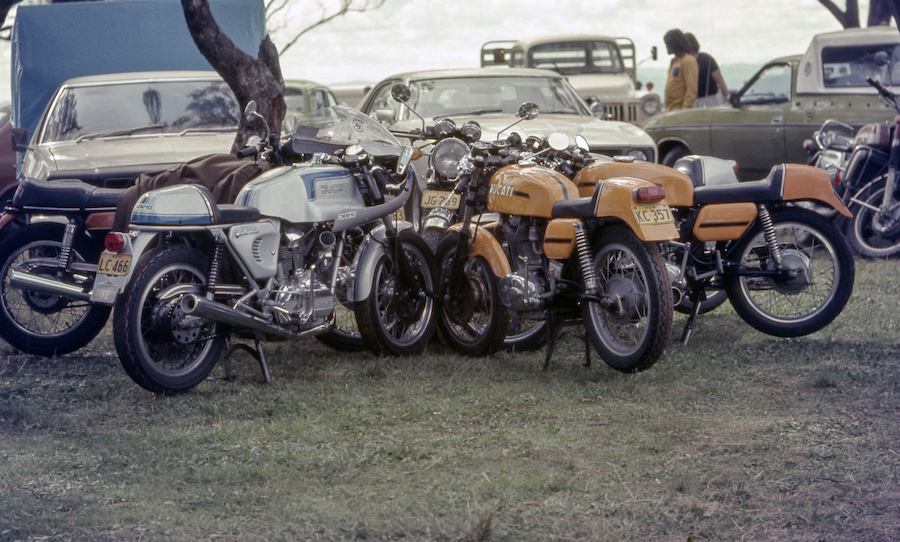

The ‘round-case’ 864cc Ducati 900SS he was entered to ride at Bathurst was originally intended to be raced at the Castrol Six Hour in October 1974. This means it would have been built in mid-1974. And here the controversy starts because production of the square-case 860GT, from which the 900SS soon evolved, only started in September that year.

Ducati officially launched the 900SS, with square rather than round cases, in August 1975, long after Easter’s Bathurst races – though Ducati had been racing 864cc versions of the round-case 750cc in endurance events since May 1973.

It seems that Blake’s Ducati was a pre-production version of the new 900SS, and the Bathurst controversy centred on its ability to beat the powerhouse Kawasaki Z1 900s on what was considered a horsepower track.

Last away, Blake had 20 laps to get back into contention. One thing in his favour was that he could go the distance without refuelling, unlike the thirsty Z1s.

In typical ‘Snakey Blake’ style, he applied himself to the job, grinding out lap after lap at near record pace to win by the length of Conrod Straight. The victory was a world first for the Ducati 900SS.

As Blake rode into the pits, officials were waiting to take the bike off him. But they knew nothing about ‘round case’ and ‘square case’ Ducatis, they were simply looking at the potential that the motor was massively oversized…

Ducati’s Bologna headquarters eventually verified it was a genuine factory bike and not a hotrod bitsa, but doubts continued to linger in some people’s minds.

Factories fork out for fame

With Australian road racing in its prime by the mid-70s, Bathurst became an important testing ground for the Japanese factories and their top riders.

The 1976 event saw works rider Masahiro Wada bolster Team Kawasaki while Yamaha sent out Ikujiro Takai on the latest TZ750. Willing set the first 100mph average on his Kel Carruthers-prepped TZ750, but the internationals were soon on record-breaking pace as well. Takai won the main event, the 30-lap Unlimited GP, from Willing and Wada. A day earlier he also won the Unlimited International, running three laps above the magic 100mph mark, with a top speed of 300km/h.

Takai won again in 1977 and the following year the Yamaha line-up included Hideo Kanaya, American Wes Cooley and GP great Mike Hailwood.

One of a few riders supplied with special long-distance fuel tanks, Kanaya made it a three-peat for Yamaha in the Unlimited GP while Willing did the same in the Unlimited International.

The introduction of the long-distance Arai 500 race in 1979 turned the focus from two-strokes to endurance/Superbike-spec four-strokes. The inaugural three-hour classic was won by Tony Hatton on a works-spec Honda RSC996 after fancied frontrunner American Reg Pridmore crashed his Kawasaki Superbike.

As well as heralding a new decade, 1980 saw the Arai 500 reach its true potential in only its second year. Here was a glamour race that fans, now riding the new wave of Japanese multi-cylinder roadburners, could really relate to.

Among the 45 teams entered, Honda had several RSC racers, now boosted to 1062cc, and other exotica included a Yoshimura-spec Suzuki and NCR Ducati. Centre of attention was the Kawasaki Z1000SR ridden by Gregg Hansford and Jim Budd. It was the first year the factory endurance bike had been seen in Australia, and the Z1000SR had led but failed to finish a month earlier at Oran Park’s Coca Cola 800, missing out on the $10,000 first prize.

The same amount of prize money was spread across the whole Arai 500 podium at Bathurst and fans expected a purpose-built endurance racer to win. But in an indication of how fast and reliable the big roadbikes had become, the podium was filled with riders from the Improved Touring and Production classes.

Michael Cole was outright winner on his Improved Touring class Honda CB900 with Garry Thomas second and Alan Hales third on their Production class 1100cc Suzukis. Like the Isle of Man TT races, it took more than just the latest technology to win on the Mountain.

How Bathurst started

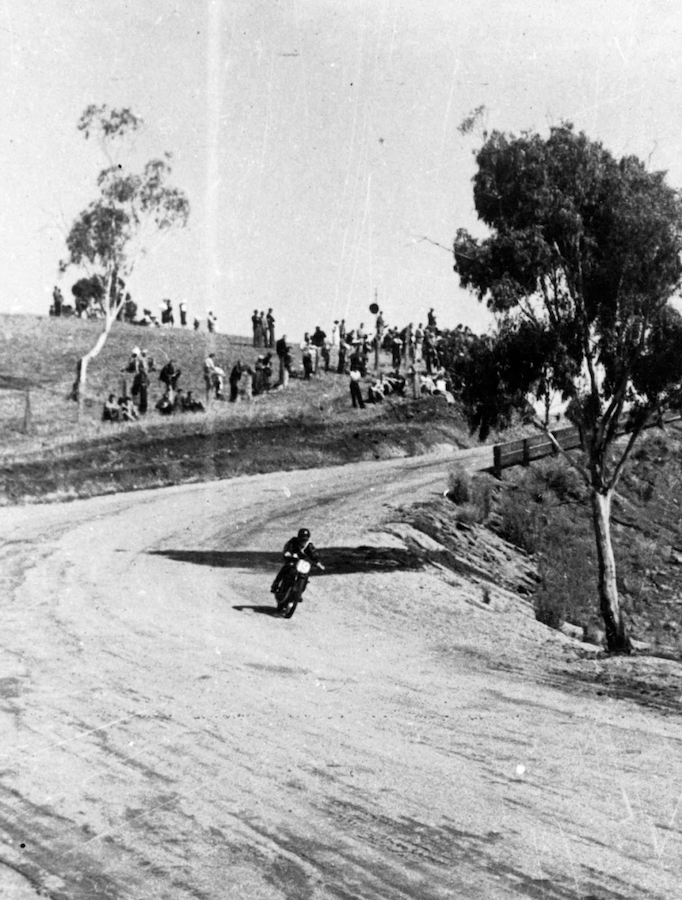

With its twists and turns and lack of run-off, it’s hard to believe the Mount Panorama circuit was actually built for motorcycle racing, not cars.

The circuit only received government finance after local officials said its main purpose was as a scenic drive for tourists. Of course, it was always meant to be a racetrack.

The first event was a combined meeting in 1938 that included the Australian Motorcycle TT and the Australian Grand Prix for cars.

The track was praised by visiting Isle of Man TT racer hero Stanley Woods, the Marc Márquez of the 1930s, who described it as world class.

The Mountain hosted Australia’s most important motorcycle races decade after decade, right up until Phillip Island was reactivated for a World Championship Grand Prix in 1989.

Before that, though, Mick Doohan (far right)proved in 1988 that the unique circuit at Bathurst could still change a young rider’s life. His win in the final 1000cc Australian Grand Prix there was a stepping stone to the world 500cc championship the following year, and ultimately five world titles.

Eye candy

All through the years, Bathurst has attracted some of the world’s most exotic motorcycles, including production models, racers and prototypes, plus some amazing specials.

Suzuki’s radical rotary RE5 was used as an official marshal’s bike in 1975. It had only just gone on sale in Australia and, at nearly $2000 with unproven technology, its appearance at Bathurst was a clever PR ploy.

One of the attractions for Bathurst spectators was the chance to see the latest racebikes from the world’s biggest manufacturers.

Ron Boulden stunned the paddock in 1980 when Yamaha’s new TZ500G was air-freighted out from Japan. And the production version of Kenny Roberts’ 1979 world title-winning two-stroke walked away with the Australian 500GP, giving the new model its first win.

Any coverage of Bathurst in the 70s wouldn’t be complete without mentioning Vaughan Coburn’s TZ fairings. Automotive artist Alan Puckett had been pushing the boundaries with ever more risqué paintjobs, but it wasn’t so much the nakedness as the positioning of the Playboy Vargas-type maiden in relation to the rider that aroused most interest…

Danger and death

Riders were always close to the edge at Bathurst, as illustrated by the two photos you see here.

The one on the right shows Len Willing, Warren’s younger brother, almost brushing the Armco on his TZ750, while in the main shot Gary Coleman is flat on the tank as his TZ750 lofts the front wheel passing the drive-in theatre on Conrod Straight. Until recently, Coleman was a key member of Valentino Rossi’s MotoGP team.

There were many crashes at Bathurst but surprisingly few deaths considering how little run-off the circuit had. However, four fatalities in four years sparked a review of track safety: Ross Barelli crashed his RG500 Suzuki fatally in 1976; Ron Toombs, in a much heralded return to the circuit, died in 1979; and Ian Dick and Rob Moorhouse died in separate crashes a year later.

By Hamish Cooper