Greg Pretty sits inside the concrete wall at Bathurst’s GTX Bend, sipping reflectively on a steel tin of Carlton Draught while he fiddles with the ring-pull clip (photo at right). Moments earlier he had been on target to claim second place in the 500GP on the Yamaha-Pitmans TZ500. But as Pretty started the last lap his fuel tank ran dry.

After he had dismounted and pushed the bike behind the newly constructed barrier, a local sitting with a few mates at the top of a driveway ran down and handed him the beer.

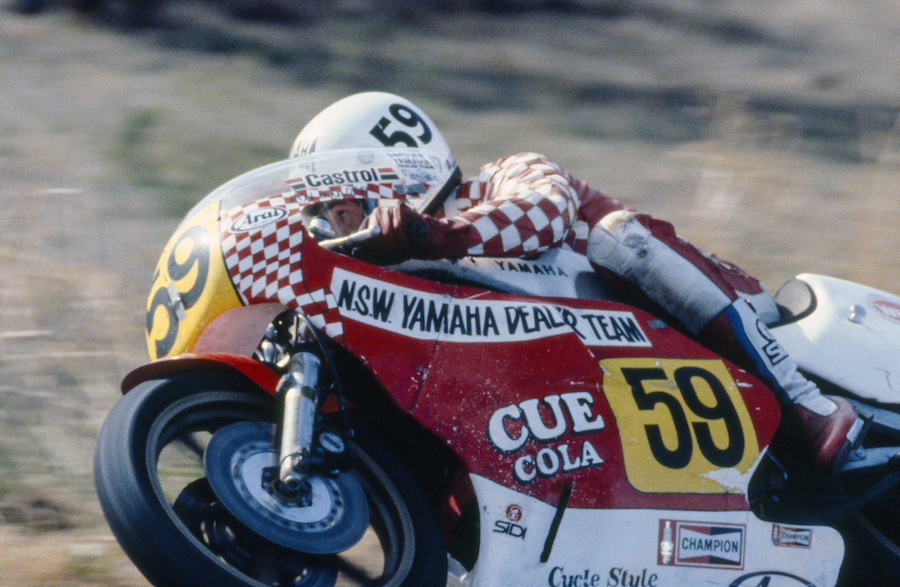

This photograph, taken by Phil Aynsley in 1981, sums up a golden age of motorcycling. It shows the connection fans had with riders at Bathurst, a bond similar to that experienced today between Isle of Man TT racers and spectators.

For decades Bathurst was the most spectacular motorcycle weekend in Australia. Fans fed off the raw emotion of the racing and the hedonistic bonding that campfires, the consumption of cheap alcohol and a shared experience of riding to the event could concoct.

Pretty was one of Australia’s rock’n’roll racers of the period. Off the track, his impish good looks and sense of humour gave him more than a touch of Bon Scott rock-god invincibility. On the track he was often unbeatable.

This was a time when youngsters could make a living doing what they loved. And for Pretty that was racing motorcycles, driving fast cars and generally living the dream. He had been the Aussie sensation of 1979, winning the Australian Unlimited (1300cc) Road Racing Championship, along with the $13,500 Swann Series. The next year he flew to the UK with fellow South Australian Jeremy Burgess. While Pretty struggled as a privateer and returned home, Burgess went on to forge a career as a GP kingmaker crew chief.

Back at Bathurst in 1981, Pretty had plenty to prove. Had the ‘gap year’ in the UK blunted his talent? Did he still have the fire in the belly necessary to conquer The Mountain? It was a typical Bathurst script that brought out the fans in huge numbers.

At Pretty’s disposal was his old crew chief Mal Pitman, a Yamaha TZ500, a TZ750, and a secret weapon – an XS1100 converted to chain drive. Two months earlier Pretty had taken this XS1100 to victory in the Coca-Cola 800 at Oran Park. Although it was Australia’s richest road race, it was merely a sideshow to the main event at Bathurst.

Pretty started the weekend with determination and skill. He won the 60km Unlimited GP by seven seconds on the TZ750 and then the glamour Arai 500 Endurance race by a lap on the XS1100.

The Arai victory, over 81 laps, hadn’t been easy. Pretty had had to nurse his worn rear tyre over the final stages and was lucky that his main challenger, Rob Phillis, had been delayed when a rag got caught in his rear wheel during a fuel stop.

The 500GP race was the feature event of the final day but its 120km race distance caused fuel concerns for both Pretty and fellow TZ500 rider Ron Boulden. Boulden dominated on his Warren Willing-tuned TZ500, while Pretty was running a strong second when the fuel ran out less than 5km from home.

And so he sat on the sidelines, nursing his beer and a few regrets. It’s a poignant moment, made even more so by the fact that we know now this weekend at Bathurst was the last big high of Pretty’s career. He was signed by Honda for 1982 but couldn’t recreate the genius sparked by his relationship with Mal Pitman.

After the race finished the winners headed off around the circuit in the London Trading Company’s Ford Falcon ute to soak up the applause of the crowd. In another moment that sums up the camaraderie of Bathurst racers, they stopped to pick up Pretty. The big yellow ute continued and fans could see the winners at close range, including the man who did everything possible to get on the podium but ran out of luck on the last lap.

Mac attack

Easter 1982: Big crowds, big bikes. The gruelling Arai 500, now in its fourth year, was the showcase and ultimate test of the latest and greatest Japanese four-cylinder roadbikes. As well as an engine having to survive three hours at full throttle, a rider had to hope the tyres and suspension could cope with the constant pounding of Bathurst’s unique mountain course.

A few years earlier 900cc had been considered a lot of motorcycle muscle. But by the early 80s production bikes were being raced in capacities up to 1300cc. The Arai 500 had an 1100cc limit for 1982, so there was a fair bit of last-minute activity to get bikes entered at the right capacity.

Several ‘prototypes’ with one-off frames had been entered in previous years, but had yet to win. What won this event was factory reliability, not experimental technology.

That all changed when Kiwi Rodger Freeth finally broke through to win on Ken McIntosh’s Suzuki four-stroke special. Freeth’s Suzuki was down on power and top speed compared to the frontrunners. It had finished the New Zealand season in 1200cc form, and to get it back to 1100cc the high-compression Yoshimura pistons were replaced by stock GSX1100 items, while milder cams were installed for reliability.

As the race neared, pundits had their money on the Mick Hone Katana 1100cc superbikes of Rob Phillis and Mick Cole. Despite appearing to handle much better than the Katanas, the Team Honda CB1100RCs of Andrew Johnson and Greg Pretty had been disappointingly slow. And no one was counting out John Pace on the Peter Molloy-built 1100cc Suzuki.

An indication of how the top teams had detuned to last the distance was the fact that the Production sub-class wasn’t that far behind the front-runners in lap times. Some big names in this class were Peter Byers, Neil Chivas, Roger Heyes, Rod Cox and Neville Hiscock.

Freeth spent the first half-hour shadowing the leading bunch of Phillis, Pace and Cole. Then, on lap 15, he picked off Cole and slowly reeled in Pace before closing in on Phillis. He was giving up at least 10km/h to Phillis down Conrod Straight, but the superior handling of the compact McIntosh Suzuki came into its own over the top of the mountain.

Then Phillis starting experiencing front brake and tyre issues. Freeth eventually finished some two laps ahead of Byers, with Wayne Clarke another lap further back. Finally, a ‘prototype’ had won the Arai 500.

Freeth then finished second in 1984 and he won it again in 1985 on a single-shock version of the McIntosh chassis. By this time almost 30 roadgoing replicas had been produced. Eventually 50 Bathurst Replicas were sold, many through Mick Hone’s Melbourne Suzuki dealership.

Twin peaks

Bathurst mirrored major motorcycle trends throughout the ’70s and ’80s. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the number of Ducati specials that raced on the Mountain in the mid-’80s.

Battle of the Twins was becoming a worldwide alternative class to the racing establishment, even running as a support event to the Daytona 200 in the US. Australian tuners joined the fray and a squadron of Ducati TT racers turned up to Bathurst in 1984. Among them were Ron Young, Ian Gowanloch and his right-hand wrench Arthur Davis with riders Chris Oldfield and Pete Muir. Other riders on TT2 Ducatis included Graeme Morris and Lindsay McKay.

These little machines had earned the reputation of being the equivalent of a four-stroke GP bike. Their sound and performance excited fans but frustrated the main players on factory machinery.

Bob Brown and rider Kevin Magee took the TT2 racer to a new level with an F1 750cc Ducati that was eventually bored and stroked to 851cc. Magee was running fifth in the 1985 Arai 500 until the bolts sheared on his rear sprocket.

The following year two ultimate versions of the air-cooled Ducati racer appeared: the Montjuich and the DB1 Bimota. Ducati importer Frasers had enough clout with the factory to give the Montjuich an unheralded world debut at the Sydney Motorcycle Show. Then the pre-production prototype stamped with the number 001 was raced at Bathurst by seasoned campaigner Pete Byers.

Meanwhile, Gowanloch and Oldfield were developing a potent version of Bimota’s DB1. With help from tuner Pete Smith, it was eventually bored and stroked from 750cc to 985cc where it made 100bhp (75kW). It soon became a crowd favourite, but getting it to hold together for the length of the Arai 500 was a challenge.

Eye candy

Through the years Bathurst has attracted some of the world’s most exotic motorcycles, both race and prototypes, and some amazing specials.

Perhaps the best example of lateral thinking was Greg Pretty’s chain-drive XS1100. Tuner Mal Pitman realised the shaft spline on the engine’s right-angle drive unit would fit a countershaft sprocket from a TZ750. He used TZ wheels and sprockets, and made up a swingarm to suit. The engine also received a race kit from Yamaha, another indication of how close some Australian retailers were to their manufacturers.

Also memorable was John Pace’s exotic Kawasaki-powered Moriwaki, which ran a nylon drive sprocket in 1981, and the MV Agusta that William McCulloch raced at Bathurst in 1982.

In 1983 Andrew Johnson took Honda’s V3 Grand Prix RS500 to a new lap record. Later that year Freddie Spencer would win a world title on an RS500. Mal Campbell took over RS500 duties for the 1986 meeting.

Kevin Magee won the Arai 500 in 1986 in only his second year of competition on the Mountain. His Yamaha FZ750 had a factory race kit fitted. Also in 1986, Michael Dowson won the 250cc-350cc double on GP-spec Yamahas.

Andre Bosman and Dave Kellett then made a clean sweep in the 1987 Sidecar races on their immaculate outfit.

And after a six-year absence the bikes returned to Bathurst in 2000. Kevin Curtain won all his six races on Yamaha’s R1.

Bad Bathurst

Bathurst’s popularity for motorcyclists waned in the mid-’80s after years of riots.

In response to big clashes on the Mountain in 1981, police brought in the newly formed Tactical Response Group the following year. Sadly, the situation didn’t improve. There was the annual confrontation and dozens of police and fans were injured, with more than 100 bikers arrested.

As well, draconian police monitoring of the crowd, which could involve several policemen confronting a solitary rider entering the campground, dulled spectator enthusiasm.

A study undertaken later by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research found that centralising police operations in a compound on top of the mountain had ‘institutionalised’ the violence. In other words, the compound had the effect of creating a battleground. Add in alcohol, hot weather and no entertainment other than ‘police baiting’ and a powder keg was lit.

The police responded with baton charges and a request for water cannons. One news report described the annual scene at the track as “like a medieval fair”. Typically, more than 1000 race fans would lay siege to the compound for hours, hurling rocks, bottles and petrol-soaked toilet rolls.

More heavy-handed police action and a booze ban in 1986 resulted in fewer than 10,000 people attending the races that year.

Crash course

The scene at the top of this page wouldn’t happen today: A trackside worker in jeans runs towards David Sinclair, who has crashed his TZ750 at the exit to BP Cutting at the 1982 meeting.

And the scene below wouldn’t happen today either: In 1981 Roger Heyes crashed on top of the Mountain and is tended to by officials while a fellow racer, Kiwi Neville Hiscock, runs to the scene to help.

Sidecar history

Margaret Halliday made history at Bathurst in 1984 when she became the first woman to win an Australian Grand Prix, partnering Doug Chivas to victory in the Sidecar GP.