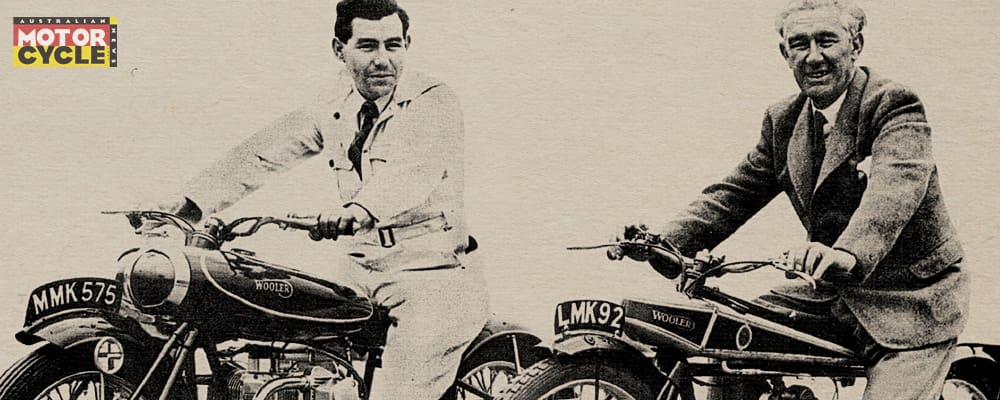

This is the story of Dallas Rankine and Dick Huurdeman and would become known as the Duke of Wellington.

Wellington, New Zealand’s capital city, has always been a “Funkytown”, to quote late-Seventies US disco act Lipps Inc.

Crowded around an ocean bay with steep, forested hills as a backdrop creates an edgy setting for this mini-city of 400,000. For well over 100 years, Wellington has inspired generations of free thinkers and has always punched above its weight, whether in the arts, technology or business.

Modernist short-story writer and poet Katherine Mansfield was born there, as was Hollywood blockbuster film director Peter Jackson. William Pickering, a pioneering space rocket scientist who headed the California Jet Propulsion Laboratory for 22 years until 1976, started life there.

More recently, Sam Morgan showed typical Wellingtonian business acumen. As a struggling student he founded Trade Me, New Zealand’s largest online auction house, later selling it for $NZ700m.

Wellington has also staked its place on the world motorcycle map. In the 1970s the Hiscock brothers, Dave and Neville, launched their international careers through Wellington Motorcycle Centre. One of New Zealand’s most successful dealerships, it was a powerhouse of production racing success.

In the 1980s Robert Holden became the next Wellington generation to start a career with WMC. Holden’s international career has been well documented. What hasn’t been widely reported was his enduring relationship with racer-tuner Dallas Rankine and his small team of Wellington-based innovators.

It culminated in a project that used those local free-thinking elements of technology and artistic design, along with the business skills to finance it all. Begun in the early 1980s, this crazy adventure ended in a funky home-brewed Ducati special being raced at Daytona and in Europe in the early 1990s.

Dallas Rankine’s hopeless addiction to Ducatis started as an engineering student who scrabbled together the money to buy a Ducati 750 GT. Then came a Sport, followed by a 1975 750SS square case. He started club racing on the Ducati, eventually ending up riding in the 1978 Castrol 6 Hour at Manfield, north of Wellington.

A year later, Rankine totally immersed himself in motorcycling, taking over British Motorcycles and Spares in Wellington. This was the time when British motorcycles were on the way out but Rankine could see an opportunity to cater for an upcoming niche market.

“In the lull between British bikes being ‘current’, their demise and then the resurgence of the classic movement I bought out dealers around the world wanting to rid themselves of the old stock,” he says.

Many containers were brought in and Rankine began a highly successful worldwide mail-order parts business. However this wasn’t his life focus.

“My passion has always been with Ducati,” he says. “The bike business financed the racing.”

By the early 1980s Rankine was racing a Harris-framed Kawasaki in the Open class and his old Ducati 750 in Production. Everything changed when he bought a Harris TT2 replica rolling chassis from UK Ducati dealer Steve Wynne in 1983.

Rankine would soon strike up friendships that would shape his life and one of the most important was mechanical engineer Dick Huurdeman. A great lateral thinker, his early 1960s 350cc Manx special was just one example of his problem-solving abilities. Nicknamed Bucephalus (after Alexander the Great’s warhorse), undoing just a few nuts and bolts removed the frame and forks from the engine for quick mechanical repairs between races. Its single-spine frame held the oil and was built several years before the Egli design came on the market.

Huurdeman and Rankine started a long journey with that TT2 that involved methanol, nitro-methane and engine capacities ranging from 600cc to 940cc.

“While Dick and I both came up with the ideas, it was Dick who did all the dirty work,” says Rankine.

Built to take on the two-strokes in the F2 class, the TT2 had some of the best components available. The Honda RC30 front fork and Koni rear monoshock had been modified by UK suspension expert Maxton, and had Spondon adjustable yokes. Brembo Goldline brakes were matched with Marchesini magnesium wheels.

With a dry weight of just 125kg and power ranging from 80hp to 114hp (the 940cc version running on a nitro-methanol mix) the TT2 needed a top rider.

Rankine soon found one: Paul Pavletich. A professional racer who would go on to win every class of racing in New Zealand that he entered in a stellar career, Pavletich gave Rankine’s TT2 project credibility.

New Zealand’s new Formula Two class pitted GP-type 250cc two-strokes against Supersport-type 600cc four-strokes. Pav’s string of victories against tough competition inspired the team to greater efforts.

Continual experiments with the engine eventually led to a 940cc version running a 37 percent nitro-fuel mix, allowed under NZ racing rules at the time. This turned it into an Open class winner, gathering up several NZ TT championships and a reputation as the bike to beat in the country’s popular street-racing series. It would finally be retired in 1995, with more than 200 race wins.

As the years progressed, greater efforts were required to stay in front in the F2 class, so things started to get really funky in 1986.

The Duke of Wellington

“Luke Taylor, my business partner but based in the UK, had a lot of contacts,” says Rankine.

“He introduced me to ex-pat UK frame-builder Steve Roberts.”

Based just a couple of hours north of Wellington, Roberts had already gained prominence for his advanced designs of the Formula One Suzukis being raced in Europe by Dave Hiscock.

He soon came on board Rankine and Huurdeman’s next project, which would get the nickname the Duke of Wellington. With weight-saving and handling performance the goal, Roberts designed and constructed a gas-welded alloy twin-spar frame that contained the fuel, with a header tank above to increase capacity.

The front fork was a Forcelle Italia with Spondon adjustable yokes and the rear a Maxton-modified Koni F1 shock, mounted in a cradle underneath the frame. This kept the shock cool and allowed access for easy adjustment of the rising-rate suspension.

Fully assembled and with oil but no fuel, the compact racer weighed just 122kg, an amazing effort considering Ducati’s own factory TT2 racer weighed 130kg completely dry.

Detail of the Duke of Wellington’s fuel injection system

Detail of the Duke of Wellington’s fuel injection system

The engine was based on a current-model Ducati 750cc F1 two-valver, downsized and converted to four valves. It used the larger engine’s 88mm bores but the team made its own 49mm short-stroked and lightened crankshaft. This brought engine capacity down to the 600cc class limit. And running on methanol allowed a 14:1 compression ratio.

Don O’Connor, the NZ Ducati importer who would get heavily involved with Rankine over the next 10 years, and machinist Graeme Sutton helped with some of the specialist engineering.

“Wellington is a small city but with international air and sea ports, and associated specialist maintenance workshops, including a foundry, we had local resources to call on for a complicated project like this,” says Rankine.

UK-based Taylor liaised with Godden Racing, which supplied a pair of modified four-valve speedway heads. Huurdeman’s powers of lateral thinking were stretched to the limit to work out how to fit valve-spring heads with internal cam drive to an engine designed for desmodromic valve operation with the cam drive on the side.

The solution was a set of bespoke camshafts that did away with the desmodromics but allowed the original Ducati cam-drive system to work. Rather than use carburetors, the team adapted an American Hilborn mechanical fuel injection system. Originally designed for drag racing at full throttle, the system needed a lot of modification with a fuel pump driven off the rear camshaft. When you twisted the throttle, engine revs rose, spinning up the fuel injection delivery rate.

Ignition was a lightweight, battery-powered and total-loss electronic Interspan unit, as used in speedway racing.

“We ended up with a very over square engine,” says Rankine. “It would rev to over 14,000rpm.”

It also idled at 4000rpm!

Proof of the design was an immediate 85hp at 12,500rpm, indicating a lot of potential from the tiny 600cc capacity. However, its Achilles Heel was the camshaft drive, which broke after only short engine runs.

“Drive to the cams was changed from chain to belt and back to chains,” says Rankine, giving an indication of the effort put into problem solving.

The Duke of Wellington never faced the starter’s flag but Rankine began sorting it in several track test days. Much of the bike was experimental, with a lot of the detailing not complete.

“The initial reason for the build was to keep the air-cooled Pantah-based bike competitive with the increasingly faster opposition,” says Rankine. “Meanwhile, despite my fears, the two-valve Pantah engine did remain at the pointy end of the field.”

The team managed to coax more power from the ageing two-valver, while handling was greatly improved by adapting Roberts’ underslung rear suspension system.

“While there was plenty of potential in the alloy four-valver the incentive to develop it further diminished when Ducati announced the 851 Superbike,” says Rankine.

By now, Robert Holden had joined Pavletich in Rankine’s small team. The introduction had come through Don O’Connor, who had brought Australian Bob Brown’s rapid TT2-based Pantah to New Zealand for Holden and racer-journalist Alan Cathcart to campaign at selected meetings.

“This started a long-term racing relationship with Robert, Don, Luke Taylor in the UK and myself,” says Rankine.

“Robert would race for us here in NZ, then for Luke in the UK in our off season.”

Brown, Rankine and O’Connor joined forces to acquire one of the first 851 homologation Superbikes for Holden to race in WorldSBK and other events with Brown as crew chief.

It was a disaster.

“The bike wasn’t particularly fast and not very reliable,” says Rankine.

Holden was entered at Australia’s Oran Park round but didn’t front the starter after countless issues, mainly revolving around reliability and setting up the electronic fuel injection.

Just a few days later the season final at Manfeild in New Zealand proved just as embarrassing.

“Our first effort ended with a DNS and Robert only got about 200 meters in the second leg before it was all over,” says Rankine.

The more Rankine and Huurdeman looked at the 851 the less they liked it.

“As well as the engine management issues we thought it didn’t handle well and was too heavy,” says Rankine.

However, there was potential in the water-cooled, DOHC engine. Perhaps a factory engine could be installed in the Duke of Wellington’s alloy frame.

“We thought we could shoe-horn this into the alloy frame and have a very light bike,” says Rankine. “We had to buy another complete 851 from the factory as we couldn’t get just an engine.”

Faster, much faster, but also fragile…

Up at Roberts’ workshop the team found the 851 engine wouldn’t fit as the water-cooled DOHC heads were physically much larger than the SOHC air-cooled Godden heads.

So Roberts built a similar twin spar frame, this time in thin-gauge mild steel so modifications could be done as the bike was developed.

“In effect the alloy-framed Godden-head four-valve Duke of Wellington morphed into the steel frame with the new 851 engine,” says Rankine.

Now totally stripped, the original Duke of Wellington’s frame spent the next 30 years hanging up in the rafters of Roberts’ workshop.

“We brought over the mechanical fuel injection system from the alloy four-valver along with a lot of the running gear to build the bike that became known as Fast & Fragile.”

It was fast because it weighed 150kg, some 25kg lighter than an original 851, and the engine eventually produced 155hp at 11,000rpm (on methanol), compared to the 109hp of a first-year 851-888 (on petrol).

Shorter and more compact than a standard 851, the chassis featured Honda RC30 fork, mag wheels and Brembo brakes with a Lockheed adjustable master cylinder.

It was fragile because Ducati crankcases of that time were like eggshells.

“We probably went through 20 sets of cases,” says Rankine. “At one stage they were stacked up to the ceiling!”

The cause of this angst was the monster engine.

“We immediately fitted the factory 888 cylinders and a 906 Paso crank so pushed out the capacity to 940cc,” says Rankine. “Then we made our own cylinders with a 99mm bore and our own 64mm crank to get a capacity of 985cc. This was many years before the factory got near this size.”

Anticipating crankcase breakages Rankine and Huurdeman reverted to a system they had used on Ducati’s air-cooled Pantah engine. They removed the alternator, cut off the end of the crankshaft and made a replacement outer cover-plate to strengthen the most stressed side of the crankcases.

“This modification, along with careful relieving of the stress points, took two days alone,” says Rankine.

Another issue was the quality of replacement crankcases.

“Each time we ordered a new set of cases from the factory, they were different, either in the material, the surface finish or the webbing,” says Rankine, explaining how the factory was chasing reliability issues themselves.

Other tweaks included making their own cylinder studs, as the factory originals would stretch, and extending the swingarm pivot through the crankcases to secure it to the frame with an extra support bearing on the drive side.

The Hilborn fuel injection was tricky to set up but the team was more familiar with this than the unknown standard Ducati electronic version. The fuel pump was belt-driven off the end of the crankshaft where the starter motor usually sat.

The first version was finished in a bold red paint scheme just in time for Pavletich to start NZ’s 1989-90 F1 summer series. Despite all the headaches of a season-long development while actually racing, Pav ended second in the championship to Yamaha’s Simon Crafar.

The yardstick of performance for Fast & Fragile came in a support race for the 1989 World Superbike finale at Manfield. In an open practice session, Pavletich lined up Aaron Slight’s WSBK Kawasaki Superbike as they entered the fastest part of the circuit.

“Our bike passed the Kawasaki like it was chained to a post,” Rankine recalls.

It sure was fast, but the fragile nature of the project hobbled any attempt at a race victory as the sky-high compression kept blowing head gaskets. Back in the workshop the problem was fixed by fitting cooper rings in machined grooves.

As the new World Superbike Championship was finding its feet, Battle of the Twins, Pro Twins and BEARS racing was booming worldwide.

It was inevitable that Rankine and Co would want to get involved, after all their main rival in NZ’s BEARS racing was John Britten’s wonder bike from Christchurch. Fast & Fragile had many classic confrontations with both the precursor Britten and the first V1100, the big-bore version of Britten’s final V-twin.

Over three seasons, Pavletich and Holden alternated riding duties and Fast & Fragile finished second, third and fifth in the NZ F1 championship, then won the 1992 F1 TT title, one of the country’s most prestigious series.

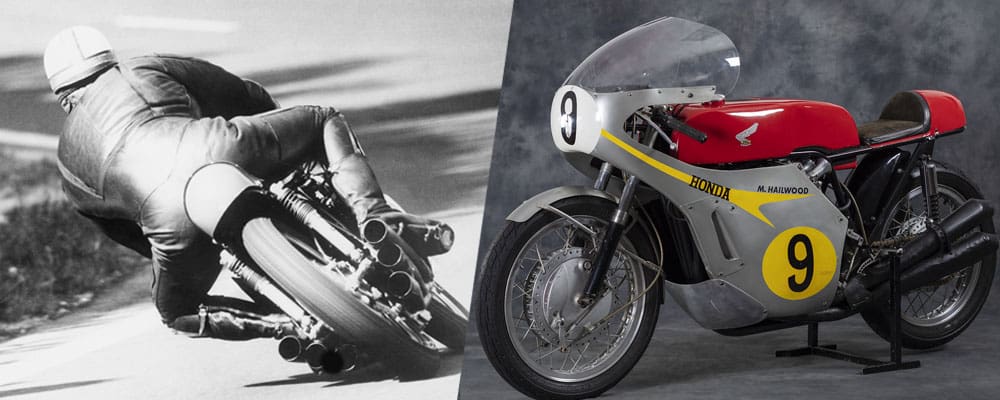

Plastic Fantastic and the aluminium racers Steve Roberts built in the early 1980s

Plastic Fantastic and the aluminium racers Steve Roberts built in the early 1980s

TAKING ON THE WORLD

In the northern summer of 1991, Huurdeman took the bike to Europe and the UK for Holden to race under the banner of Southern Cross Racing.

It had several wins and garnered huge attention, giving Rankine the confidence to take it to the ultimate test: the early 1992 Pro Twins event on Daytona’s high-speed oval. The twins race was almost as big a deal as the Daytona 200, with top American Superbike racers entered.

“We figured we just had to be there,” says Rankine, “but we were rather naive with our preparation, running a new big-bore engine converted to petrol.”

This was the year John Britten’s all-new V1100 arrived with Andrew Stroud on board and was set for an easy win when the battery went flat. And while the Britten got most of the attention, Fast & Fragile, now painted a bold blue colour, had plenty of enthusiastic fans looking it over.

Several factory-spec Ducati Corsas were entered and Rankine knew that by now they were as light and powerful as his bike, with a new reputation for reliability. This struck home when their untried engine seized in practice and they had to slot in a less-powerful spare. Even so, Holden hit a top speed of 256km/h, just 10km/h slower than the Britten, which had a much larger engine.

Holden ended the race in fifth after the Britten expired. Ahead of him were four Ducati 888s and behind a flock of highly-tuned frontrunners from previous years.

Robert Holden leads Jason McEwen’s Britten at Manfeild in 1992

Robert Holden leads Jason McEwen’s Britten at Manfeild in 1992

We underestimated the prolonged high speeds on the banking,” says Rankine.

“Perhaps with another year under our belt we could’ve done better.”

This was the high point and swansong of the remarkable Fast & Fragile, created from the remains of the Duke of Wellington project.

“We retired the bike in late 1992,” says Rankine. “Further power improvements meant more frequent crankcase and crankshaft breakages.

“We were very much ‘nuts and bolts’ with our modifications. We would try something, either to get more power or better reliability then, if it didn’t work, try something else. It was ongoing development as we fixed each problem as it arose.

“Of course, eventually Ducati got far more horsepower and far better reliability than we could have ever dreamed of.”

The final chapter

Rankine’s relationship with Holden continued on a different level.

“Don O’Connor brought out Steve Wynne and his Ducati Corsa for Robert to race in the 93/94/95 domestic seasons,” says Rankine. “Robert raced for Steve in the English summer season.

“We also had two Supermonos; the first one Robert finished second in the TT in ’94 on. He carried on to win the ’95 TT. Then he qualified top of the leaderboard in the Singles, Superbike and Superstock for the ’96 TT, before losing his life in the last practice session.”

His death ended Wynne’s and Rankine’s involvement in motorcycle racing.

Approached to comment for this article, Steve Wynne, now retired to New Zealand, said: “My three favourite riders, out of many I sponsored over 30 years, were Hailwood, Haslam and Holden; three Hs. Not in any particular order, or for any particular success, but because we were all doing it for fun and the love of the sport. Over those 30 years I never had a fatality or even a serious injury. I retired the same moment Robert died.

“Losing a friend just wasn’t fun, or racing.”

The death had the same effect on Rankine. He sold his business, which now exists as British Spares based in the South Island, and is semi-retired on an avocado orchard.

Holden on Fast & Fragile in 1996, just a few months before he was killed at the IoM TT

Holden on Fast & Fragile in 1996, just a few months before he was killed at the IoM TT

“Robert was not only a remarkable rider but also a good friend,” says Rankine. “His positive attitude and humour abounded, even in times of adversity.”

Huurdeman kept up his passion for motorcycles. In 2005 he rode his 1955 Norton 600cc side-valve single from China to Holland for his younger sister’s 70th birthday. He died in 2015, aged 82.

However, one man keeps racing today. At the age of 61, Paul Pavletich competes in the historic F1 class, adding more trophies to the cabinet in his man cave.

“He’s one of those guys who the older he gets the more powerful bike he races,” says Rankine, referring to Pav’s 170hp Yamaha FZR1000.

The Dukes of Wellington were resurrected in time for this year’s 40th anniversary of New Zealand’s Classic Racing Festival. Except for the incorrect forks on the first Duke of Wellington, they are in original form.

The display of these fascinating little racers creates a living time capsule of a crazy period of New Zealand motorcycle racing. This was a brief period when funky designs built with a mix of engineering and artistic ambition were financed by a clever businessman with all those skills. The result was race and championship wins.

Much was achieved in just a few years.

Rankine with the restored Duke of Wellington

Rankine with the restored Duke of Wellington