The RC213V’s carbon brakes make a shrill sound as the factory Honda comes to a stop in the Misano circuit pitlane. Waiting for it is one of the mechanics. Facing the approaching rider, he grabs the upper part of the front fairing with both hands and stabilises it, as Pol Espargaro jumps off the bike and strides towards his box.

The Japanese V4 is quickly pushed backwards into the garage to a waiting Marco Barbiani, who plugs a 15-pin cable into the dashboard. The 34 year-old Italian begins the download to his computer while keeping one ear on the all-important first impressions from the rider.

Speaking to his crew chief Ramon Aurin, Espargaro states: “It’s spinning too much out of Turn 3.”

Racing is all about speed. And not only in terms of the motorcycles themselves. Because in this game, time is strictly limited and therefore precious. This is the opening free-practice session at the 14th round of the 2022 MotoGP World Championship in Misano. There’s just 45 minutes to get the rider comfortable and the bike somewhere in the ballpark so the following sessions can be used to refine the base setting.

While he listens to the conversation between the rider and the crew chief, Barbiani has 30 seconds to check that everything looks in order, ensuring the engine temperature is working in a safe range, among other things. The mouse moving, his fingers typing on the keyboard. He listens to Espargaro’s feedback and quickly compares not only the previous year’s data to try and reduce the Turn 3 spinning complaints, but also test rider Stefan Bradl’s and LCR Honda rider Takaaki Nakagami’s. He must remain calm but work fast and efficiently: a plan must be strictly followed, as it is vital for Espargaro to end each session inside the top 10.

Just a few minutes have passed since Barbiani plugged into the RC213V. He nods, turns towards the crew chief and is ready to speak.

Six hours later, in the quiet space of one of the team’s trucks usually used by Espargaro to warm up his body and suit up, Barbiani sits down to talk about his job in detail. The first words he uses to describe his role within the team is: “Data-wise, I’m the crew chief’s eyes and in part his brain.”

Born and bred in the Italian peninsula, Barbiani worked in domestic and international racing series from 2011 before making the switch to MotoGP and HRC in 2016.

After a handful of years supporting Cal Crutchlow’s LCR Honda squad with plenty of success, Barbiani was drafted into the factory team in 2019 to work with five-time world champ Jorge Lorenzo. He worked with Alex Marquez in 2020 and has spent the last two seasons with Pol Espargaro.

How many things can you see once you connect the cable to the bike?

There are about 1000 parameters which come from more or less 300 sensors, with each sensor giving a number of parameters. For example, for each inch of every lap I see the leaning angle, the speed, the braking style, where the rider changed gear and the revs numbers in that moment.

Basically, what I see and understand from the computer can be divided in two areas: what happened to the RC213V and what the rider did. Within the team we all have access to the information. It is also shared with Honda’s satellite team, which also shares its data with us.

What are some examples of the type of data you might share?

I’m talking about lines, throttle control and so on. All the riders’ inputs. I can see where Pol and Takaaki Nakagami are braking in a particular corner. I can clearly see where they start to brake and how hard they brake, how much pressure there is on the levers.

So let’s go back to this morning. Espargaro says the bike was spinning too much out of Turn 3. What do you do?

I verify why he’s spinning, or better I find out why he feels he’s spinning and then I check and see if it is true. I compare with other riders and the previous year’s data. I know if the spinning is too much because I had previously set an ideal range. Maybe the tyre pressure is not correct. Or the traction control is not cutting enough power.

I can say let’s check the tyre pressure. Or, for example, suggest Pol to take the turn in third gear and not in second gear like he did previously, because I noticed that another Honda rider is doing so. Maybe I can suggest that we need less power there, so he can open the throttle in another way, or use another map. He has nine combinations involving power delivery, engine braking control and traction control.

Your tools are your computer and your brain, correct?

It’s an intellectual job. I’ve got to translate numbers in a few clear words. I’ve got to consider that the riders can’t think, while they ride. They would make mistakes. So all my analysing and thinking, which come from years of experience, could result in a few words: ‘Take the corner in second’. That’s it.

From your perspective, if the rider complains about something, can you have a genius idea that suddenly solves everything?

I must say that we can modify something on the machine but the benefit the rider can gain is through his actions, which I can suggest by telling him to do something differently in his riding style. This makes for three times the benefit of just making a change on the bike.

How specific are riders in their comments?

A rider rarely says ‘we need more engine braking’. The comments are more basic, like ‘I can’t stop the bike’ or ‘the bike is not accelerating like I want it to’.

Are all practice sessions treated the same?

In FP1, FP2 and FP3, Espargaro has to push in order to directly access to Q2, where 10 riders, plus two promoted from Q1, which involves the rest of the grid, will battle for the pole positions according to the results of the combined three free-practice sessions.

So he’s very aggressive and doesn’t apply what he’ll do in the race, where he’ll have to save the rear tyre and maybe manage fuel consumption. Consequently, we work on the race pace only in FP4 and, in fact, may base our choices for the race on only a couple of laps.

What is an example of a mistake a data engineer might make?

You forget to consider an option regarding the bike’s front discs, so you go into the race and the temperature is too high and the performances go down. That can happen if you didn’t consider aspects like the rider’s weight or the slipstream.

Cal Crutchlow was pretty vocal about his disappointment in losing you to Jorge Lorenzo. Even though that was the same brand, how do you feel about a data engineer following a rider to a new manufacturer when he switches teams?

No, I think that developing your know-how towards the bike is the main thing. You can improve the quality of the gathered information and help the development. Of course, if you spend two or more seasons with the same rider, it helps because you can count on the experience from the previous year.

But if I work 10 years with Honda, I will be much better than working 10 years with the same rider with different manufacturers. With the same brand I see the differences in data of many riders and not just one. And a rider may not be very consistent in his performances.

How did you end up in the Repsol Honda squad?

Before getting my bachelor degree in Mechanical Engineering, when I was a university student I made an internship with the Honda San Carlo team in the 125cc Italian championship. It wasn’t easy to get that chance. In 2010 I went to all the races of the Italian series of motorcycles, cars and trucks, and handed out 265 resumes. My career goal was to be a racing mechanic.

So you didn’t know you were likely to become a data engineer?

That came later. After my internship, the team kept me and Moto3 was introduced. I knew how to use 3D softwares and helped them develop the first swingarm for a Honda that was not produced by the Japanese company. The bike had a cost of about 25,000 euros ($A39,000) and we needed to modify it in order to be more competitive than our opponents. That became the final project I delivered in order to get my university degree.

When did you switch to working with data?

It was a small team so we had to do everything ourselves. At the same time, speaking about the general context, it was the beginning of this kind of development. I was in charge of deciding which sensors to mount on the bike and to do it.

So I basically built the systems, so I got a deep knowledge about them. In the end, having the opportunity to work with a good team on a national level meant I had all the time to do these things and work on them with the required time. Had I accessed a world championship team, this opportunity would probably have been missed because everything would be in a rush. Let’s say that we could do experiments. That was sweet.

So when were you promoted to the world championship?

In 2012, in Moto3 with Mahindra. In the lightweight class the data engineer and the mapping engineer are the same person. Things change in MotoGP, when I arrived in 2016 with the LCR Honda team, the rider was Cal Crutchlow. Together we won three races in MotoGP.

It’s wasn’t easy, as an independent team. In the top class there are two people for the two jobs. In 2019, I joined the factory team and worked with Jorge Lorenzo, then Alex Marquez and Pol Espargaro.

Did any of these riders teach you something valuable?

Lorenzo surprised me. He had a lot of experience on other bikes, having previously raced with Yamaha and Ducati. He did something unique: his first launched lap in each run was often the fastest. He wanted to find the limit right away; it was one of his main characteristics. He wanted to simulate the opening lap of the race. From my point of view, that was amazing.

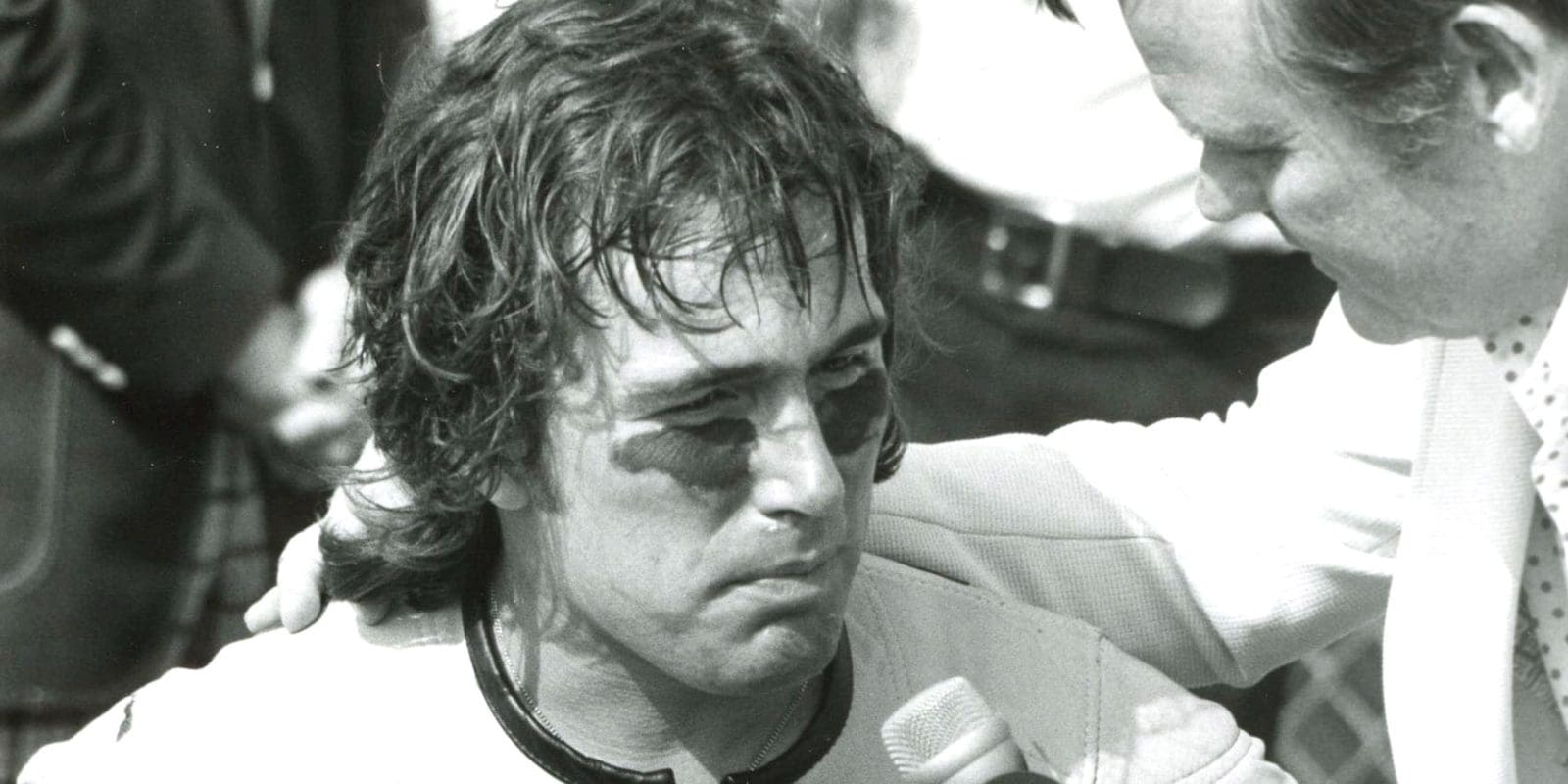

Interview Jeffrey Zani + Photography G&G and AMCN archives