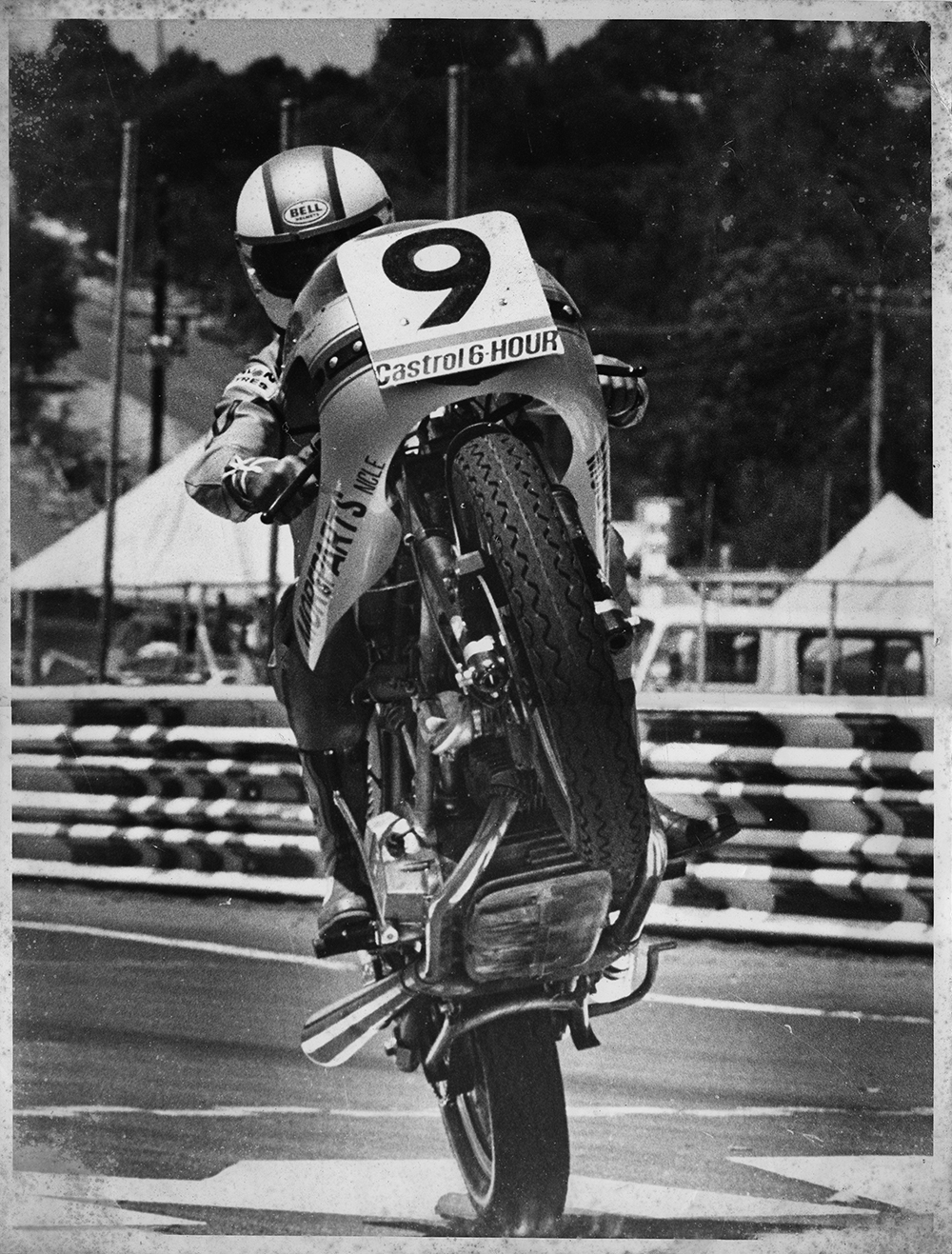

Amaroo Park and the Castrol Six Hour race epitomised the freewheeling Australia of the Seventies.

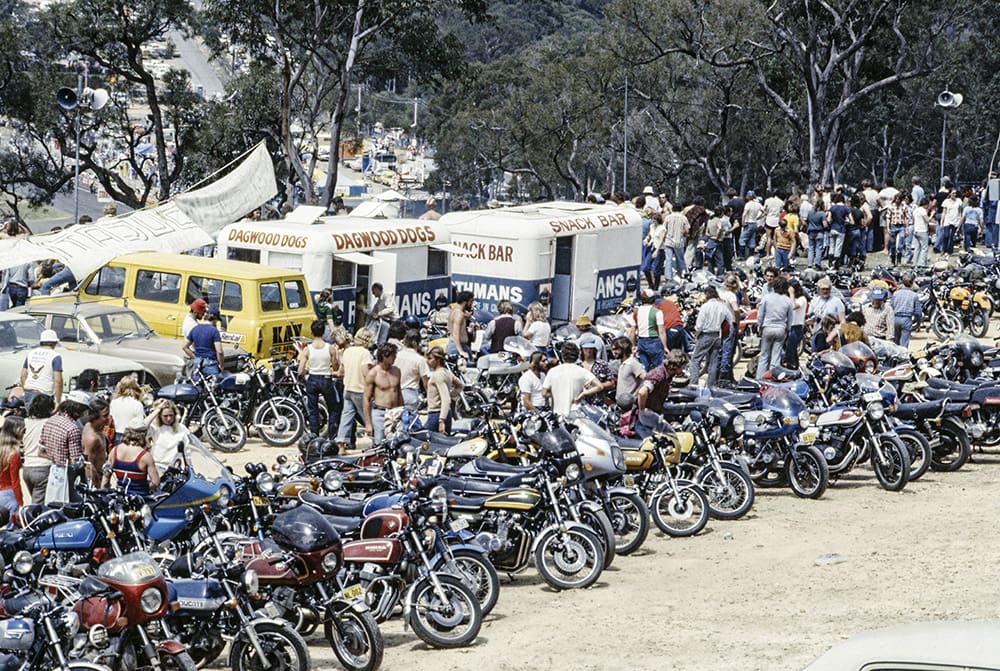

In a setting almost like a Roman amphitheatre, the nation’s best racers flogged the latest production motorcycles for six hours every October. Watching this gladiatorial spectacle were thousands of sun-baked fans, drinking cans of lager, puffing on a durrie and eating Dagwood dogs.

As the booze and the strong spring sun took hold, the men went topless and the women stripped down to skimpy outfits. Meanwhile the bikes roared around and around just metres below them. What a place. What an event.

Carved out of the floor of a rocky valley in suburban Sydney, Amaroo Park snaked 1.9km around a series of cliffs with blind corners and long lengths of Armco barriers.

It would not be licensed if it was built today, but all through the 1970s it hosted Australia’s most popular motorcycle race, the Castrol 6 Hour.

Where are they now, those R90S BMWs, Yamaha Triples, Z900s and Honda 4s? And the guys and girls who rode them to Amaroo Park every year?

Where are they now, those R90S BMWs, Yamaha Triples, Z900s and Honda 4s? And the guys and girls who rode them to Amaroo Park every year?

The event helped launch the international careers of a generation of riders from both Australia and New Zealand. If you could win this race, you could win anywhere in the world.

At its height in the late Seventies, the Amaroo Park Castrol 6 Hour attracted as many as 10,000 fans, many of them riding their motorcycles to the event, and filling the circuit to overflowing.

In 1977 Mike Hailwood took the event to a new level of interest as he started what would become a fairytale return to racing, and the Isle of Man TT.

The following year Yamaha’s shaft-drive XS1100 and Honda’s outrageous six-cylinder CBX 1000 brought multi-cylinder madness to the event.

In 1979 Suzuki’s new GS1000 lapped the entire field within three hours, taking race professionalism to a new level.

We’ll concentrate on these three years, the focus of our archival photography, but first some history.

And a 750SS race-bike with a centre-stand?

And a 750SS race-bike with a centre-stand?

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Amaroo Park was built by Sydney businessman Oscar Glaser, whose diverse company North Sydney Traders owned the land. His original plan was to create an American-styled country club with a motorsport complex as its centrepiece.

He founded the Amaroo Country Sporting Club Ltd and started with a motorcycle scrambles course that opened in 1962.

Amaroo is an Aboriginal world meaning “beautiful place”, and the bush setting was certainly that. However, Glaser’s grand plans never came to fruition and the circuit always had only basic facilities.

Rather than a GP-spec circuit, a narrow 1.9km bitumen course was built. Its first event was a 30-lap production motorcycle race in 1967 won by Larry Simons on a BSA Spitfire.

The Australian Racing Drivers Club took over running Amaroo Park in 1969. The following year Australia’s largest motorcycle club, the Willoughby District Motorcycle Club, held the first six-hour production race, called the Castrol 1000.

There were 75 starters split across Unlimited, 500cc and 250cc classes. A Le Mans running start ended in a pile-up triggered by several 250s. Moments later, another crash on lap two brought the ambulance out into a traffic jam of racers, causing yet another bingle.

Teams hold the bikes as riders run across in a Le Mans start, with marshals following for the initial lap

Teams hold the bikes as riders run across in a Le Mans start, with marshals following for the initial lap

At the end of six hours second-placed Craig Brown sat on his Honda looking like he’d been duped in a card game. Beside him victor Len Atlee was basking in the euphoria of winning on his Triumph Bonneville 650. A $1400 cheque was written for the winning team.

Kiwi Brown, a chef by trade, had been on target for that win but he was a youngster who’d never raced in a major event before. Brown had been beaten by two of Australia’s most experienced road racers, Atlee and Bryan Hindle, on a bike entered by Sydney dealer Ryans of Parramatta.

Brown’s solo privateer effort proved the potential of Honda’s four-cylinder machines, which next year swept the leaderboard.

There were many interesting aspects of the 1970 event that weren’t largely recognised at the time.

Third outright was the tiny T20 250cc Suzuki two-stroke of Dave Burgess and fourth were Bill Horsman and Ian Ardill on an R5 350 Yamaha, precursor to the giant-killing RD350. Two-strokes were here to stay, despite being considered noisy, smelly and prone to piston seizures.

Also, an all-female team of Sandra Davis, Janet Middleton and Linda McFarlane put in a great effort on another R5 350. Surviving a crash, they stuck it to the boys and finished ahead of many of them in an event of attrition. The women had bought and prepared the machine themselves.

Another woman, Peggy Hyde, teamed with Rod Tingate to finish fourth in the 500 class on a Mach III Kawasaki. Earlier that year at Phillip Island the 26-year-old Peggy had become Australia’s first female winner of a road race.

Fans on the trackside banks and cement dust on the track

Fans on the trackside banks and cement dust on the track

Kawasaki’s demon two-stroke triple set the fastest lap of the race in the hands of Ken Blake.

What had started as a glorified club meeting soon ballooned into the nation’s most important motorcycle event and captured the public’s imagination. How did this happen?

It was simply the right race at the right time. The Seventies were a rollicking decade for Australians. The population’s average age was late 20s. Australia’s economy was roaring along, fuelled by a resources and agricultural export boom. Tax concessions had kick-started a local film industry and a homegrown recording industry was becoming the strident voice of youth. It was a great time to be a cashed-up Australian.

Motorcycling and surfing soon became the two most glamorous pursuits of this booming generation of 20-somethings.

Retailers of motorcycles and related accessories and clothing soon learned that competing in the Castrol Six Hour brought kudos and boosted sales.

With a bit of clever PR the Castrol Six Hour got television coverage, first on Channel Seven and then the ABC. Amaroo Park entered a golden age.

HAIL “MIKE THE BIKE”

By 1977 the Amaroo Park Castrol Six Hour had managed to deliver a different slice of spectacle each year. From eligibility controversy to heroic solo rides, the event was always in the headlines.

Publicity stepped up a notch when nine-time world champion Mike Hailwood competed that year. His arrival at Sydney airport was a news event and his choice of motorcycle, a Ducati twin, a talking point as Kawasaki’s Z900 had dominated production racing for the past couple of years.

However, the great fascination of the Six Hour at Amaroo was how smaller, theoretically uncompetitive bikes could dominate.

In recent years various Ducati and BMW twins had upstaged bigger Japanese rivals. Even two-strokes from the smaller classes had challenged for wins. What Hailwood described as “a bit of fun” ended up with second place in the 750cc class and sixth outright.

Teamed with Jim Scaysbrook, Hailwood was part of a privateer team on a Ducati provided by Newcastle motorcycle wreckers Moreparts.

Money was so tight that Hailwood and Scaysbrook practised, qualified and raced on the same set of tyres.

Scaysbrook took the running start as Hailwood’s old F1 car ankle injury still hampered his mobility. Everything went to plan and Mike the Bike did two stints in the saddle, just what the bumper crowd had come to see.

Apart from Hailwood the race was a ripper and was screened live on ABC TV.

Former winners Joe Eastmure and Ken Blake rode consistently fast and with fewer fuel stops on their BMW twin to shut down the Z1 Kawasaki challenge. Blake’s third win in this event helped finance his entry into top-level European racing.

Second were Jim Budd and Neil Chivas on a Z1. A surprise third were Alan Hayes and Dave Burgess on an under-rated Kawasaki Z650, ahead of Ducati team-mates John Warrian and Ron Boulden and BMW legendary German racer Helmut Dahne and Tony Hatton.

Everything went like clockwork for Hailwood and Co and the strong finish laid the groundwork for another season of Production racing at tracks around Australia.

When the pair returned for the 1978 event, the Ducati and its riders were wearing the colours of major sponsor Golden Breed youthwear.

SHAFTED BY YAMAHA

Anticipation was just as high as in 1977, but Hailwood’s team was blighted by practice crashes that required two all-night rebuilds. A blown big end kept them out of qualifying so they had to start from the back of the grid.

Nevertheless, Hailwood fought his way into 15th place overall and was leading the 750 class when he handed over to Scaysbrook, but a seized gearbox ended their valiant charge.

The Hailwood drawcard aside, the race was full of technical interest.

Yamaha’s new shaft-drive XS1100 had made its appearance in 1977 as the marshals’ bikes. This year it took on Honda’s outrageous six-cylinder CBX 1000 and Suzuki’s new GS1000 in a battle of the DOHC multi-cylinders.

Graeme Crosby put his CBX 1000 on pole but a fuel issue resulted in a seized engine..

As the race unfolded the Team Avon’s XS 1100 battleship of Jim Budd and Roger Heyes prevailed over its Suzuki GS1000 and CBX rivals.

Second were gutsy Queenslanders John Warrian and Terry Kelly on the Ducati 900SS. Mick Cole and Dennis Neil were third on their CBX.

An indication of how the competition had hotted up since 1970? A lone T140 Triumph 750 Bonneville finished last but completed one more lap in the six hours (a total of 313) than the 1970 winner, less than a decade earlier

It was entered by Melbourne dealer Peter Stevens and prepared by Sydney dealer George Heggie. Riders were Bob Payne and Martin Hone.

The Yamaha victory meant a shaft-drive motorcycle had won Australia’s biggest road race two years in a row. Bizarre. Also of significance was the fact that Budd and Heyes had benefitted from Team Avon’s slick tyre changes. The race was won as much in the pits as on the track.

SUZUKI’S FINEST HOUR

Another year, another bumper crowd at Amaroo Park. Look closely at the photos and you’ll notice the tribal nature of fans. Three-cylinder Yamaha XS750s parked together, clusters of Ducati V-twins, rows of big Japanese four-cylinders from Kawasaki, Suzuki and Honda. Also a surprising number of BMW twins, one of the most expensive road bikes of the day.

Honda’s new thoroughbred, the CB900, was the talk of the meeting and it didn’t disappoint, with American hotshot Wes Cooley brought out to race one (see Where Are They Now, on p129).

Dennis Neil put his CB900 on pole, ahead of the Z1 Kawasaki of Graeme Crosby and Japanese team-mate Akihiro Kiyohara.

Alan Hales and Neil Chivas turned their third place in qualifying into a solid maiden win for Suzuki’s GS1000, the factory’s first Six Hour victory.

As well as a new Six Hour record of 360 laps, they had lapped the entire field by the halfway mark; six hours equals 360 minutes – a lap a minute, average. Second were Greg Pretty and Jim Budd on a Yamaha XS 1100 with Len Atlee, winner of the 1970 event, third with Gary Coleman on another XS 1100.

But the Castrol Six Hour and Amaroo always had an extra magic trick up its sleeve.

This time it was the spectacular crash of Dennis Neill, who totalled his CB900 on the pit-straight Armco just before the race ended.

The 750 class was won by a young Wayne Gardner and John Pace on a Kawasaki Z650.

The next year the Honda factory would send over three of its new CB1100R models and Production racing in Australia was changed forever.

Wayne Gardner showed the ability that would eventually bring him the 500cc World GP title with a calculating and classy win with team-mate Andrew Johnson. However, the Honda really was a street-legal racer, heralding a new era in motorcycling.

End of an era

During the early 1980s Production racing started morphing into what we’d now call Superbikes.

The Castrol Six Hour remained a spectacle but in 1984 the launch of the first Australian Superbike championship took motorcycle racing in a new direction. The Six Hour was moved to Oran Park that year but the event was never quite the same. It was held for the last time in 1987.

Amaroo Park was used as a racing venue until 1998; today it has become a housing estate.

The only link to the old circuit nowadays is the lake that used to be in the centre of one of the world’s craziest race tracks.