Words Adam Child Photography Joe Dick

Ducati’s V4 Streetfighter can boast the sort of numbers that would have put it in contention for a WorldSBK win a decade ago. It wasn’t that long ago that Superbike manufacturers were chasing a power-to-weight ratio of 1:1, 200hp from 200kg was jaw dropping.

Now, a road-focussed nakedbike fresh off the Ducati production line swaggers onto the scene gloating 153kW (205hp) from a 178kg (dry) package.

The recipe? Take the firm’s V4 Panigale, remove all the bodywork, add some aggressive-looking aerodynamic wings and, hey-presto, the new Streetfighter V4 S. By the way, those double wings aren’t just for show; along with the very latest sophisticated electronics, they help to control the immense power with much needed downforce. They also look very cool, which is an added bonus.

When I chatted with Ducati’s Project Manager Paolo Quattrinu he said something which whet my appetite.

“We wanted to create a mad bike,” he said. On paper they’ve thoroughly succeeded, but on the road? There is only one way to find out.

Turn the key, and the five-inch colour TFT dash comes alive. Before firing up the V4, it’s time to select which rider mode is appropriate for your ride – Street, Sport or Race. Each one changes a plethora of rider aids and power characteristics and, as this is my first ride, I opt for Street and leave the rider aids alone.

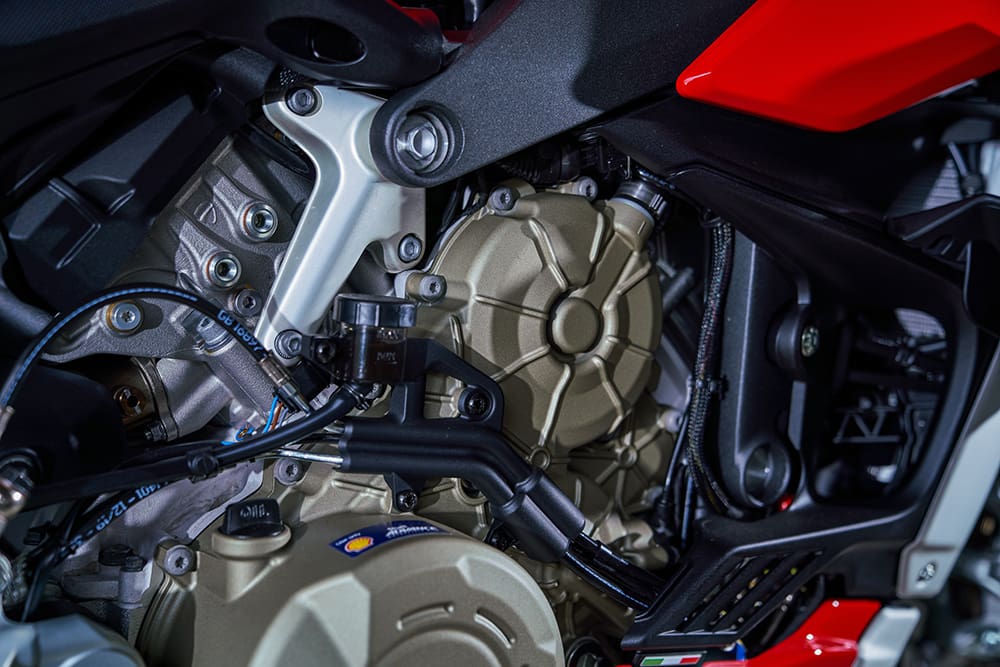

Blip the throttle (for no reason other than it sounds good) and there is an instantly familiar Ducati Panigale heartbeat to the Streetfighter. It’s slightly odd if you’re not used to the Panigale soundtrack because it doesn’t sound like a V4, more a V-twin, but that was a very conscious decision by the Italian firm, to stay true to its V-twin heritage if only in sound. And considering it’s completely Euro-4 compliant, the note sounds strong through the standard exhaust and isn’t crying out for an aftermarket system. That’s good news.

My first few kays are met with mild confusion as I negotiate a selection of small villages in England, with strict 50 to 65km/h speed limits. There is no ‘mad’. In fact, it’s like meeting Alice Cooper and finding out he’s vegetarian and plays the harp in his spare time.

Trundling along, occasionally checking out my reflection in shop windows, admiring the protruding wings on either side of the 16-litre fuel tank, the fuelling is perfect. Clutchless gear changes are smoother than the underside of a penguin (which I presume is smooth), but there’s still no madness. There’s less heat from the V4 engine that cooks your bits on the Panigale. Remove the wings, add a different badge, and this Italian could be Japanese, it’s just so smooth and easy to ride. I’d even go so far as to say a relatively inexperienced rider could jump on this thing and, at low speeds at least, not feel overwhelmed. Once you brush past the snarling teeth, this dog appears not to bite.

Okay, so the Streetfighter’s easy and delightful at low speeds, but this isn’t why the bike exists. As Quattrinu said: it was designed to be mad.

Onto the duel carriageway and it’s time to poke the beast in the eye. It’s a similar story. The revs start to build, but not alarmingly so; the power is progressive and smooth… Am I suddenly braver than I think, or does this Ducati just not feel quick?

A look about and there’s two empty lanes in front and nothing behind me, I grab fourth gear and a big handful of throttle. Holy Christ! At 7000rpm the Streetfighter wants to take off. I short-shift at 10,000rpm, way before peak torque which happens at 11,500rpm, and another massive chunk of power, possibly more than before, hits with the force of a huge barrelling wave. This is intense.

The Streetfighter’s computer limits torque in first and second gears, then adds some more in third and fourth, before allowing full fat drive in fifth and sixth. Fact is, with its shorter gearing, the Streetfighter accelerates even harder than the Panigale.

The tacho, I discovered, divides into three distinct zones: between 3000rpm and 6000rpm it’s timid and easy to live with; from 6000rpm to 8000rpm it wants to party; from 8000rpm it simply rocks… while biting the heads off bats. Even in Street mode (which gets all the rider aids working overtime) this is an incredibly fast bike, and to test the more aggressive modes I need to get away from civilisation, out into the countryside, because this is going to be wild.

Into the Sports mode, away from inquisitive eyes and it’s time to have some fun. Now the V4’s power goes from docile kitten to angry tiger the more you twist the throttle. On the road it’s almost too fast; in fact I don’t think I ever actually revved it all the way to redline at any point.

I was always changing gear around 10,000rpm, way short of the 12,750rpm point of peak power, because there is so much power on tap. My only criticism is that the quickshifter is on the sensitive side. A few times I tapped a gear by mistake or tapped two gears instead of one. But as the miles built up, the more we, well, clicked and I experienced fewer missed changes.

The EVO-2 rider aids are incredible. You have traction, slide, and wheelie control, plus engine braking and launch control. Additionally, there is cornering ABS and that quickshifter/auto-blipper. On the S model, Öhlins Smart EC2.0 controls the semi-active suspension (see breakout), which can be tailored to the rider by fixing the damping. Rider aids can be changed on the move, but deactivated only at a standstill. The excellent rider aids don’t inhibit the fun, instead they enhance it by giving you the confidence to push a little harder and start to use those 205 horses. These are some of the best rider aids I’ve ever tested and can be easily tailored to the condition and how you ride.

I was expecting the V4 S to be wheelie prone, but it isn’t. Instead, it simply finds grip and propels you forward with arm-stretching acceleration. Even with the rider aids deactivated, it’s far less wheelie inclined than I‘d have thought. This is down to five factors: wings, rider aids, limited torque in the lower gears, a 19mm longer wheelbase than the Panigale, and a counter-rotating engine.

Normally, large-capacity nakedbikes with loads of power and torque are constantly trying to pivot around the back axle. On a nakedbike, you’re sitting higher up in the windblast. When you ride fast or accelerate hard, the wind pressure hits the rider, who then pulls on the bars which lift the forks and sits the rear down. All of this means nakedbikes are more wheelie prone than fully-faired machines, as the rider acts as a sail. But Ducati has managed to reduce wheelies and increase stability and it can’t be all down to the wings, which don’t actually start working until speed increases above road-legal speed limits.

This doesn’t mean the Streetfighter is less amusing to ride. In fact, the opposite is true because this stability delivers confidence. A nakedbike with this much power shouldn’t be this stable, composed and civilised at speed.

The braking is outstanding, too, as Brembo Stylema M4.30 calipers bite down on the 330mm discs with immense power. But again, like the engine power, it’s not an overwhelming experience, just strong. You can’t ‘feel’ the cornering ABS working, not on the road, and the stoppers are backed up by class-leading engine braking control, which allows you to leave braking devilishly late.

Personally, I love the fact you can opt for the front only ABS, which allows you to have some fun getting sideways into corners. Again, the Öhlins semi-active suspension has to take some credit for the superb braking performance, as the front forks don’t dive like a scared toddler after a car backfires. They hold their composure and allow you to make the most out of the expensive stoppers.

The semi-active Ohlins Smart EC2.0 suspension is equally assured in the bends. It copes with undulations and bumps with composure and refinement. I deliberately hit notorious bumpy, horrible sections at Irish road racing speeds and the Ducati stayed composed and unflustered, it even felt like the steering damper could be redundant. Even pushing on, the handling is solid and stable, all those clever electronics, the wings, the engine’s character, that longer wheelbase and steering geometry (rake and trail are the same as Panigale) colluding to deliver a superb ride.

The seat is 10mm higher than the Panigale’s, with more foam for comfort, and the pegs lower. The wide bars and protruding wings give the feeling of a large bike, and with that longer wheelbase I was expecting the steering to be a little slower, but it’s more than happy to lay on its side like an obedient dog. Once over, the grip and feel are impressive.

We stayed away from the track on this test and will have to give the Streetfighter a thorough workout at a circuit in the coming weeks, perhaps with race rubber, to see how it performs on the very limit. But in standard form on standard Pirelli Diablo Rosso Corsa rubber, there are no negatives.

Clearly, I’m loving the new Ducati Streetfighter and to be honest I wasn’t a huge fan of the 2009 bike version, because I never warmed to the looks. However, the same can’t be said for the new V4, which is a stunner.

In the past, Ducati has tried to force a water-cooled engine into an attractive chassis, and sometimes failed. In the early days, the first water-cooled Monsters looked like a plumbing and wiring nightmare. Or maybe this was just my opinion, ’cos I loved the air-cooled engine so much. But now the new Streetfighter is neat and tidy, exhaust and water-cooling routes hidden, the finish neat. I love the extra details and touches like the Joker-style face, the stunning single-sided swingarm, and the cut-out sections in the rear seat. It looks like a bike designed from the ground up, not just a Panigale with its plastics removed.

However, for $34,200 (on the road) I was expecting a little more bling. Where, after all, is the carbon fibre, the keyless ignition and other trinkets? Yes, I know it’s an exotic Ducati but $34K for the S and $29,800 (ride away) for the standard model is serious money, especially as the competition from KTM and Aprilia are 10 to 20 percent cheaper.

While I’m grumbling about price, I have to mention the fuel consumption, which drops to 7.8L in 100km if pushed hard on the road but sits at around 6.4L or a little more in normal use. Okay, that isn’t dreadful, but the fuel light comes on prematurely between 130 and 145km while the 16-litre fuel tank only gives a tank range of 200km if ridden hard.

But, as a good friend (who’s not as tight as me) pointed out, it’s a bargain compared to the $40,890 Panigale S (ride away). And, anyway, who buys a 205hp Ducati V4 and worries about fuel range?

And let’s face it, the Streetfighter is a better roadbike with friendlier ergonomics and ease-of-use. Primarily riding on the road, with the very occasional track day, I’d opt for the naked Streetfighter every time. It will be an interesting test when we get both bikes back-to-back in the future.

Ducati’s Streetfighter is so good it makes you seriously question why you would want a sportsbike, especially if you’re mainly riding on the road. Ducati has made 205hp useable through a clever combination of chassis, power delivery, electronics, and aerodynamic wings. You can hop on, ride (or pose) around town and nip over to your mate’s for a beer, or alternatively tear up some bends, or embarrass some sportsbikes on the track. It really is as fast as your arm and neck muscles will allow.

The rider aids don’t diminish the fun or character, and it looks stunning from every angle. Yes, the Streetfighter is expensive – and thirsty – but on paper is the most powerful nakedbike on the market.

On the road, it’s arguably the best hypernaked at the moment. Only a big group test will tell us for sure.