Ever since servicemen returning from WWII decided they could improve on the motorcycles they rode in Europe, customs have been all about modifying factory bikes. We’ve created bobbers, cafés, brats, rats and a whole lot more. But have you ever considered what could be at the other end of the spectrum?

What if, instead of adding or removing parts on a factory bike, you started from scratch? Not ‘scratch’ as in a restoration project or even a parts catalogue. What if you started with nothing but raw steel, a few old parts and a whole load of talent? What if you actually built the whole bike and most of the engine yourself?

For Jeremy Cupp of Virginia’s LC Fabrications, a blank piece of paper was as good a place as any to start when he embarked on the build he chirstened Seven. “I’ve been in or around the trades for most of my life. Coming from a family of machinists, welders and fabricators, I guess you could say that I’ve got metal in my blood. I love the stuff.”

The end result, after more than a decade of honing his metal crafting skills and untold hours bombing around the local countryside, has culminated in this one-off miracle of a machine the man himself calls ‘Seven’.

You’d think that only a speedway fanatic could create something like this, but you’d be wrong. “We don’t have that ’round here. We’re more of a tractor pull crowd,” he jokes. But what they do have is bobbers and dirt bikes. “They’re what I grew up with. I like to think of Seven as a unique mix of the two.”

What’s it based on?

Looking for two-wheeled inspiration, Jeremy found himself turning to the web for some pixelated eye candy. There among the blur of paint, rubber and two-wheeled shiny things, he spotted a CAC Harley-Davidson from 1934.

Hailing from America’s golden age of speedway, most of the 20 or so built were crashed or melted down for metal during the war. Thankfully, a lucky few escaped from being dropped on the enemy and have been restored by dirt track die-hards.

CACs now change hands for upwards of US$180,000 and it’s believed only nine original examples remain in existence. With their built-for-speed looks, tool-like functionality and acres of chrome, it’s not hard to see why Jeremy was smitten. “For someone who’s seen and ridden a bunch of bikes over the years, the CAC really stopped me in my tracks.”

What it’s got

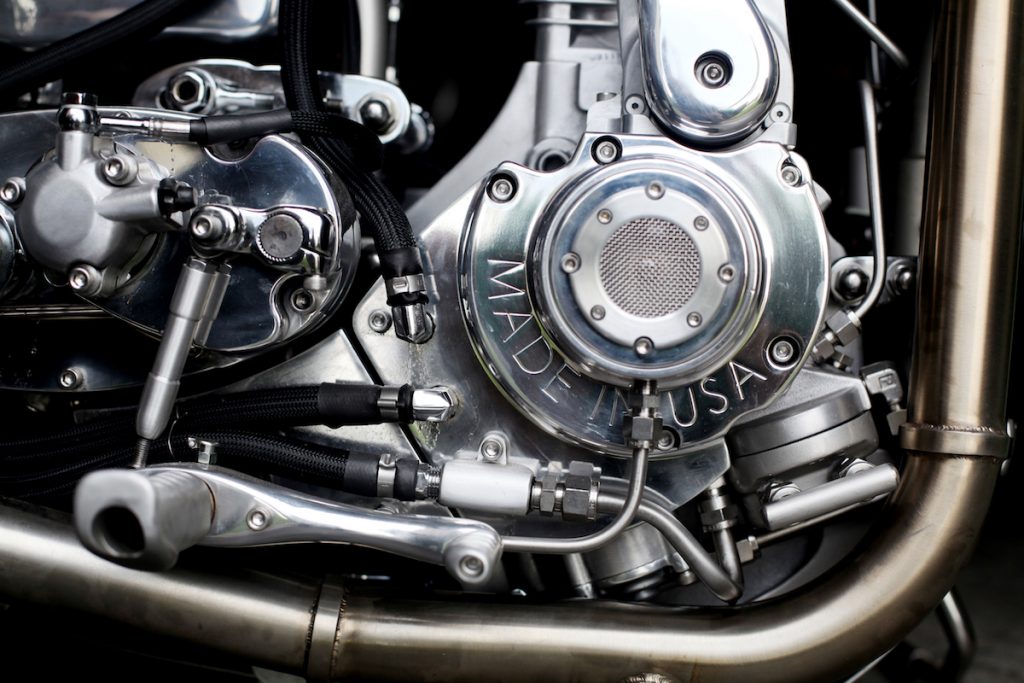

“I suppose the thing that stumps most folks is the engine,” Jeremy says. He’d briefly considered tracking down a more traditional JAP powerplant, but his mind kept returning to an old Buell Blast engine he had in his shop. Remembering a build he’d once seen that had joined some Ducati desmo heads to a Harley Evo Twin, he got to wondering.

“Being both a machinist and an engine junky, I suppose I never really got the idea out of my head. So I decided to try it for myself, but in a single-cylinder version.”

To get the cylinder into the speedway’s prerequisite vertical position, he cut the factory transmission from the cases and joined a pre-unit Triumph gearbox to what was remaining. And hey presto, you’ve just created the world’s first pre-unit overhead cam Buell. The bike’s front end is also a bit of a downstairs mix-up. Tentatively named the ‘hydro-springer’ design, it uses a 32mm Showa inverted front end for dampening with an additional springer-style leg that carries the load. Put simply, it gives the rider the best of both worlds: springer classiness and dependable cartridge fork handling.

What was tricky?

Anyone with the metalworking skills of a mere mortal would assume that mating a Buell bottom end to a Ducati desmo head would be the engineering challenge of a lifetime. Something akin to McGyver building a tactical nuclear weapon out of ciggy butts and an old Twisties packet – but not for Jeremy. During this build, his biggest test was forming the sheet metal for the tank and rear guard.

He’d previously relied on aftermarket guards and his tank-building efforts had been limited to flat sides and sharp edges. But this time he decided to push himself a little. And by ‘a little’ we think he means ‘a whole lot’.

“I love to learn new things, and I always try to plan my projects so that they force me to do something I haven’t tried before. For Seven, that challenge was hand-shaping the sheet metal. I’m pretty happy with the results.”

What’s next?

With the career-defining challenge of Seven done and dusted, Jeremy’s now eyeing off his next few projects. And although he hasn’t had any light bulb moments for another big build, he’s planning to keep himself out of trouble by completing a few smaller projects that will be sold to make the shop some well-earned money. As most customisers know from bitter experience, putting your blood, sweat and tears into a build like this rarely pays off financially. So until it does, making a bike from scratch like Seven is done for one thing and one thing only – the love of metal.

Words Andrew Jones

Photography Michael Lichter