Not long ago, Italy’s small but historic Moto Morini brand was in the bankruptcy courts, as yet another victim of the 2008 GFC crash. But since October 2018, it now belongs to Chen Huaneng, the CEO of privately-owned Chinese manufacturer Zhongneng.

He’s working hard on a nakedbike and a street scrambler, both powered by Chinese-built 650cc parallel-twin motors. Meanwhile, production continues in Moto Morini’s Trivolzio factory near Milan of its range of 1187cc models powered by the unique V-twin CorsaCorta engine.

In between times, in 2011 Moto Morini was purchased from the liquidator by two Milan-based investors, one of whom – Ruggeromassimo Jannuzzelli – took over sole ownership of the company five years later. Thereafter, Moto Morini continued its steady ride along the comeback trail. Morini’s 13-strong workforce produced 190 motorcycles in 2018, most of which were hand-built.

But as part of his plan to fuel Moto Morini’s resurgence, Jannuzzelli invested some serious cash in producing the kind of motorcycle he’d want to buy himself. That’s somewhat ironically now entered production under Chinese ownership as the Moto Morini Milano.

“I wanted a bike that’s practical, but exciting,” says Ruggero. “With a full-bodied engine that provides a thrilling ride on the open road, but is easy to use in a city – something that’s the best of both worlds. I wanted a proper motorcycle with the practicality of a maxi-scooter, but a lot more performance.”

The fact that Jannuzzelli divides his time between a rooftop apartment in the centre of Milan and his magnificent family home near Moto Morini’s factory – a 12th century fortified castle that once owed allegiance to the King of Sardinia, no less – says it all.

The man charged with creating this best of both worlds is Moto Morini’s technical chief Massimo Gustato. And he’s got an impressive CV; Bimota, where he was responsible for putting high-end models into small-scale production, from the DBX Supermoto to the BMW-powered BB3 Superbike. Before that, Aprilia Racing. He worked on the title-winning RSW125/250 Grand Prix racers and RSV4 Superbike, so this is a man who knows how to develop small-volume models cost-effectively, without sacrificing quality.

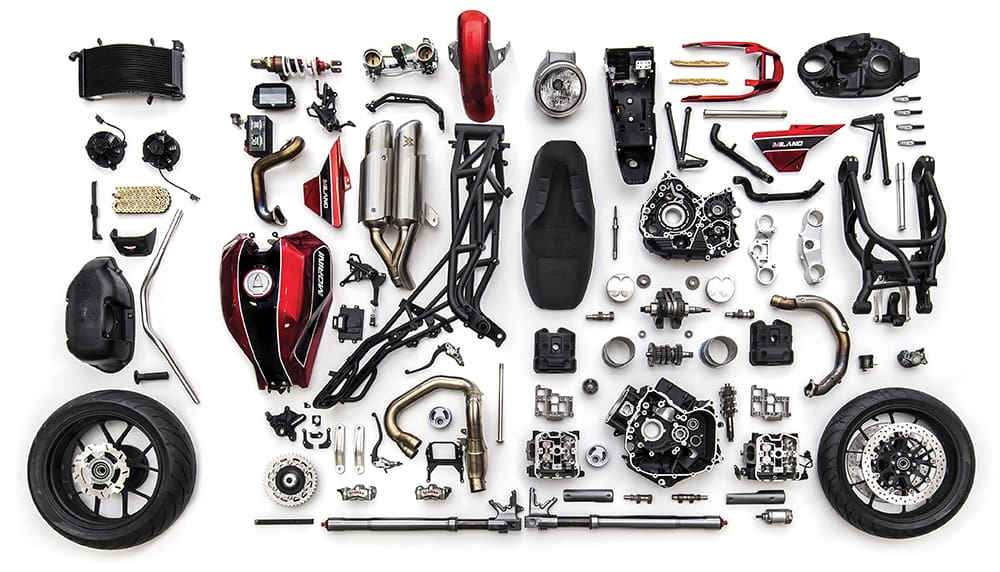

Gustato began work on developing the Milano in January 2017, and as he’s eager to underline, this entailed much more than simply detuning the Corsaro motor, and sticking a passenger seat on its Streetfighter chassis. He and his engineering team designed an all-new TIG-welded chrome-moly tubular steel frame that’s lower and longer than the firm’s Corsaro’s, resulting in a 55mm lower seat height and a likewise lower centre of gravity, with a new 30mm longer cast aluminium swingarm pivoting in the engine crankcases and chassis, thus delivering a rangier 1490mm wheelbase.

Steering geometry is more relaxed, too, with the fully adjustable 46mm Mupo USD fork giving 120mm of wheel travel set at a slightly wider 25º rake with 108mm trail, 5mm more than before. At the rear there’s a Mupo shock adjustable for rebound damping, as well as preload via a remote hydraulic adjuster, with a revised progressive-rate link, which Gustato says is more comfortable in the initial stroke of what is a reduced 110mm suspension travel.

Chassis-wise, only the Brembo braking system and forged aluminium wheels are shared with the Corsaro, with twin 320mm front discs gripped by four-piston radial calipers and a 220mm single rear disc and twin-piston caliper rear.

Switchable Bosch MP9.1 dual channel ABS comes as stock, and those forged wheels carry Pirelli Angel GT tyres, the rear a 190/55-17 which has quite a flat profile thanks to the wide six-inch rim it’s mounted on. Half-dry weight with oil/water, but no fuel is 191kg – but you’d swear it was much lighter than that, instead of just 500g less than the ZT Corsaro.

“One test we’ve performed with a blindfolded rider is to walk both bikes inside a garage,” says Massimo. “Everyone’s convinced the Milano is 20 kilos less, but it’s exactly the same weight, with a lower centre of gravity.”

Its engine has been retuned, too, to provide a broader spread of reduced power and torque, with rideability the key issue, according to Gustato.

“We used the same bottom half of the engine as the Corsaro, but we’ve modified the cylinder heads, camshafts, valves and valve timing,” he says. “We’ve reduced both torque and horsepower to create a softer, more rideable bike, but at 5000rpm there’s almost 9.8Nm more torque than the Corsaro. And while peak power is about 14kW (20hp) less, we’ve focused on improving the rideability.”

The revised camshafts have reduced lift and overlap in pursuit of that, and there’s an all-new 2-1-2 Arrow stainless-steel exhaust, whose twirling pair of header pipes ending in stacked cans on the right side, rather than beneath the seat as on the Corsaro, emit a stirring rumble of muted aggression.

The Milano’s engine management comes courtesy of an Athena ECU controlling the twin light-action 54mm Magneti Marelli throttle bodies, each with a single injector and a cable throttle – yes, this is old-school, so no choice of riding modes. Maximum power is delivered at 8000rpm with 85.4kW (115hp) on tap, while torque peaks at 6250rpm, with 108Nm. Compare that with the Corsaro’s 102.5kW at 8500rpm and 125Nm at the same 6750rpm, and it’s evident how much engine performance has been sacrificed in favour of greater all-round rideability.

But is it too much in a bike costing 15,000 euros compared to the Corsaro ZT’s 15,900 and the ZZ’s 19,900? Only one way to find out, and that was to take the Milano to the city that spawned both its creation and its name. First, though, I took the scenic route to get there, via a testing 40km ride winding through the risotto fields, which revealed that the Milano still has quite enough power to excite, but not to the extent that you keep popping the front wheel in the air in the bottom three gears under hard acceleration, as on the ZZ.

As regular readers will know, I’m the owner of an original Corsaro 1200 that’s still just as much fun to ride as it was in the week I took to ride it back to Britain from Bologna in the summer of 2007. So I was particularly interested to ride the Milano. Of course, the Milano delivers a totally different riding experience that’s evident from the moment you straddle it, and find yourself sitting much lower down than perched atop the Corsaros, with their exhaust silencers under the seat. This makes the Milano seem a more intuitive and relaxing ride, with a calmer and more measured feel thanks to the longer wheelbase and more conservative steering geometry.

All this creates a 1200cc V-twin that seems as nimble and easy-steering as a 500cc twin, and the result is a bike that’s the ultimate traffic tool – a point-and-squirt device with sure, predictable handling, and excellent feedback to the rider.

A notable aesthetic change on the Milano is its smaller 13-litre fuel tank, which narrows at the rear to allow almost any height of rider to put their feet on the ground more easily. This combines with a reshaped one-piece handlebar with taller, wider and more pulled-back grips to deliver an easier yet still fairly upright riding stance. Frankly, that fuel tank is too small to be practical, even for a city bike – the fuel light came on after a mere 100km, and while I didn’t run out before I found a petrol station 10km later, I know from my own bike that it’s a pretty thirsty motor.

But the result still very much likes to be hustled through turns, and there’s excellent feedback from the Lupo fork and Pirelli Angel front tyre to help you keep up corner speed with confidence, while the low centre of gravity makes it easy to flick from side to side in a switchback succession of bends. And that meaty motor’s wide spread of torque is easy to access without constantly changing gear – not that that’s a hardship, because the Milano’s gearshift is miles better than any Morini I’ve yet ridden, including my own.

Still, it’s a shame there’s no wide-open powershifter fitted as standard on this model like on the ZZ – it’s only available as an option, presumably to save costs, and there’s no possibility of a clutchless autoblipper system for downward shifts even as an option, because of the Milano not having a ride-by-wire throttle.

The improved gearshift proved useful once I reached central Milan, as did the quite light action of the hydraulically operated slipper clutch. The Milano’s much wider spread of torque was now very helpful in allowing me to cut through traffic from one red light to another without constantly swapping gears. Then when I could dial up some revs to outsprint maxi-scooters along any wide avenues; the Morini responded decisively, surging forward at a twist of the wrist to leave TMaxes droning in its wake.

Indeed, the Milano has a great feeling of connectivity between what your right hand is doing and the way the bike puts the power to the tarmac. There’s no digital filter to dilute your desires, just an analogue link between the throttle and the rear tyre that’s refreshingly old school, but deliciously direct. And the traction control proved very welcome riding over Milan’s polished flagstones, ditto the Bosch ABS. The Brembo radial brake package is its usual peerless self, effective without being grabby, with the twin front discs hauling the Milano down from high speed with heaps of feel as you work the clutch lever to back down the gears, and access the considerable engine braking the Gustato gang have left dialled in to the slipper clutch. The rear brake wasn’t very strong, though – pads, maybe?

You readily realise how flexible and forgiving the Milano’s CorsaCorta engine if you gun it wide open in fourth gear at 2000rpm exiting a second-gear turn, and can then relish its meaty midrange as it pulls hard and strong in completely linear mode all the way through to the fierce-action 9300rpm revlimiter, without a trace of transmission snatch. This might be unexpected for such a short-stroke engine format, which you’d normally expect to have to rev quite hard to obtain this kind of performance. While the motor has a serious appetite for revs – Lambertini claims it runs safely to 13,000rpm – it’s also content to pootle along at low, low revs in traffic.

Indeed, the CorsaCorta motor’s light-action 54mm single-butterfly throttle bodies give a clean, controllable pickup from any revs. It’s happiest operating in the 2500-6500rpm zone, so you’ll want to short-shift to stay there and surf the torque curve by holding third or fourth gear for long stretches of road over a variety of conditions.

It was hard not to be impressed with Ruggero Jannuzzelli’s legacy to the Moto Morini marque in the shape of the new Milano he’s responsible for creating. And I’m glad that Mr. Chen has decided to keep faith with the model, which he’s declared will receive an RBW throttle, a range of different riding modes – and that badly needed two-way powershifter.

With its great handling, decent performance and upright riding stance, the Milano is an electronics-lite real-world ride, where it’s up to you to harness that glorious engine’s deep reserves of performance via judicious use of the right hand. It’s a satisfying ride in traffic, because of its thrilling acceleration and outstanding responsiveness across a broad range of revs.

One year ago when I rode the Corsaro ZT I wrote that this was the complete opposite of a nanny state bike – something with two wheels and an engine that’s so gloriously non-PC you’re practically surprised that anyone is actually allowed to build bikes like this for sale any more. Moto Morini does – and it has just doubled its bets with the Milano.

Test Alan Cathcart Photography Kel Edge