Then enter the crazy bikes of the 70s.

Ah, the excessive 1970s. Tie-dyed hippy shirts, 24-inch bell-bottom jeans, crocheted bikinis, hair everywhere, rock music hijacked by punks, cricketer Jeff Thomson bowling at 160km/h, Alex Jesaulenko’s VFL mark of the century, the supersonic Concorde airliner, microwave ovens that cooked a meal in a minute… What a kaleidoscope.

The motorcycles of the era – when free-thinkers from California became part of the mainstream – were just as memorable: a Cortina engine slotted into a Norton featherbed chassis that was actually registered on the road in Australia, a dragbike powered by three Honda CB750 engines in the US and a feet-first, part-car-part-motorcycle that went into production in the UK were just a few of the amazing contraptions.

To celebrate all that 70s whackiness, we take you on an amazing journey of alternative engineering.

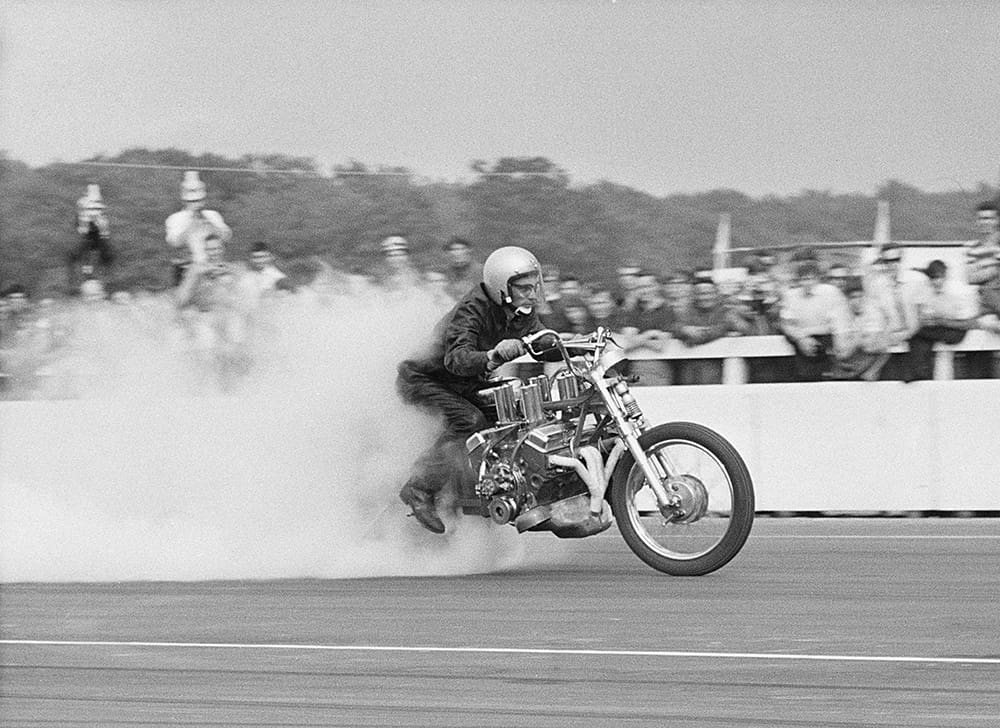

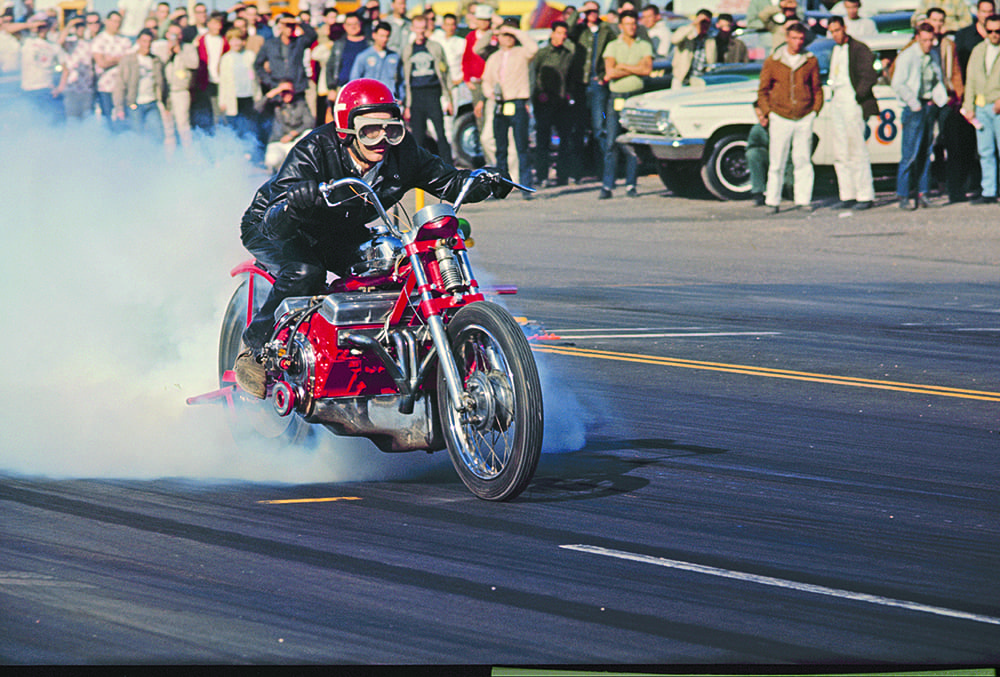

The decade started with the roar of an unmuffled V8 Chevrolet. No big deal, you think. Well think again. E.J Potter, aka The Michigan Madman, had fitted this big donk into a motorcycle frame he had lying around the workshop. He first dreamed up the idea of mounting a V8 engine in a Harley-Davidson chassis when he was 16. His childhood reasoning was that the small-block Chevy mounted sideway would be only wider, not longer, than the original Harley engine. He was right and the crazy idea spanned two decades.

Potter’s first run, in 1960 at his local drag strip, got him to 130mph (209km/h). By 1970 he was touring the world on exhibition runs and nudging 190mph (305km/h) on the 335kW (450hp) bike he called The Widowmaker. It wasn’t very sophisticated. With a direct drive system (no gearbox) the Madman would start the monster on a stand with a basic clutch pulled in and the rear wheel off the ground. Then he’d take it to full revs, kick away the stand and launch off with the smoking tyre acting as a sort-of centrifugal clutch. The rear wheel featured a cross-ply car tyre, which lasted a couple of runs only. Potter boasted: “Ignorance is a powerful tool if applied at the right time, even usually surpassing knowledge… It would feel like I was doing something that was not supposed to be even possible.”

Australia got a taste of The Widowmaker before Potter retired in 1973. His 8.68 second quarter-mile run at Sydney’s Castlereagh Dragway won him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records. Potter also built a jet-powered trike he eventually sold to Evel Knievel. After retiring, he took up tractor-pulling, using twin Allison aircraft engines in a device he called Double Ugly.

He died in 2012, aged 71.

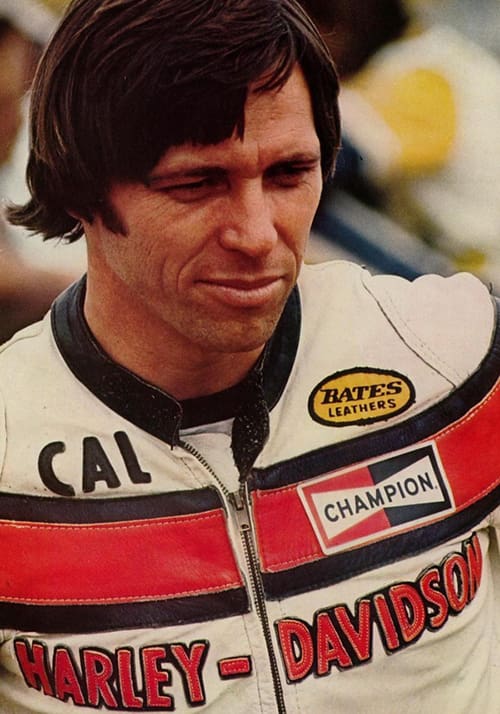

Harley’s heroes

America’s only motorcycle manufacturer was holding on by its fingernails in 1970. It was only the freakish ability of factory rider Cal Rayborn that was keeping Harley-Davidson in the performance game. He delivered back-to-back victories at Daytona’s fearsome speedbowl in 1968-69 on ancient side-valve KR750 Sportsters. With the Japanese factories swamping the US, Harley needed a serious image boost. Crazy days demand crazy people and the factory turned to a 24-year-old self-taught engineer who built a 187mph (300km/h) Bonneville streamliner on his garage floor using a largely standard Sportster engine. Sure, there were some issues – such as not being able to see out of the streamliner’s windows due to the front wheel and the rider’s knees obscuring the view.

“H-D race chief Dick O’Brien offered me $10,000 if we got a new world record and reimbursement for my hotel bill if we didn’t,” Denis Manning recalled years later.

Manning’s missile was tiny. It may have had a wheelbase of over two metres, but the bodywork was less than 60cm in diameter to reduce air resistance.

So Rayborn lay flat in the chassis, peering out plexiglass side windows and running beside the track’s centreline to maintain direction. He crashed several times learning the technique.

After his speeds approached 170mph (273km/h), O’Brien slotted in a nitro-burning 1458cc Sportster engine nicknamed Godzilla. Rayborn hit 266mph (428km/h) on his first run and 264mph (424km/h) on his return for an average 265.492mph (427km/h). This record stood until 1975 and justified the Number One logo on Harley’s advertising.

Rayborn went on creating Harley legends when he took an agricultural waffle-iron XR750 Sportster to the Trans-Atlantic Match Races in the UK in 1972. He won three of the six races to become the series joint top scorer. Crazy had suddenly become do-able.

The next year Rayborn was killed when the Suzuki he was racing in New Zealand’s Marlboro Series seized. He shouldn’t have been riding a motorcycle at the Pukekohe track in 1973. He had gone there to race a Formula 5000 open-wheeler car.

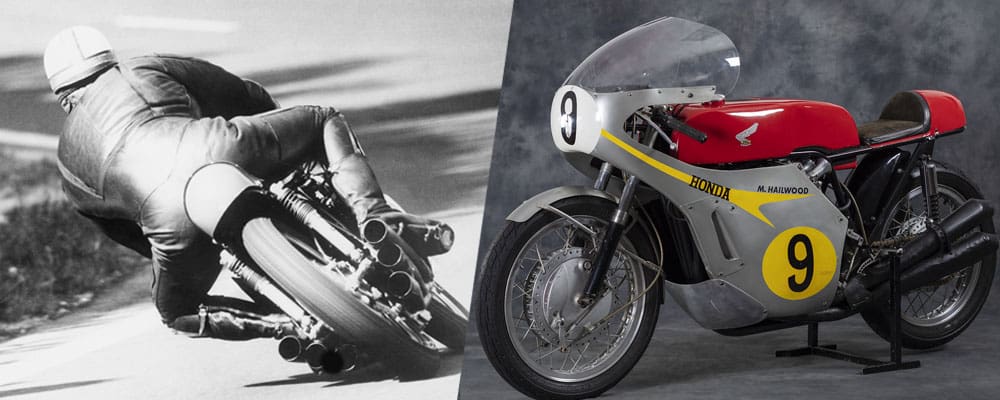

Helluva Honda

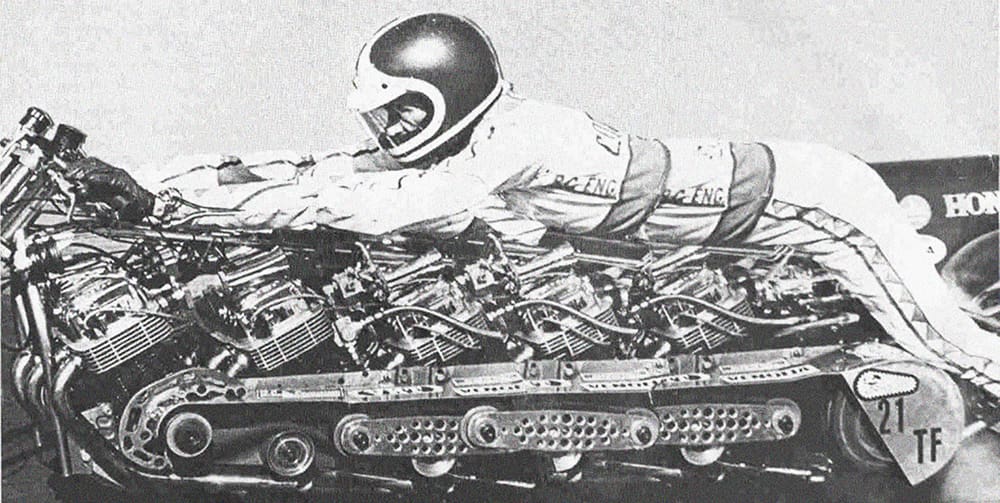

In the 1970s, too much was barely enough in drag racing. The previous decade had seen various Harley, Triumph and Norton double-engined dragbikes thundering down the strip running nitro-methane witches’ brews. Then along came Russ Collins – who turned the sport on its ear, proving the ultimate potential of untried Japanese technology. Collins developed fuel-injection, supercharging and funny fuels. He built a succession of multi-engined dragbikes using two, three and even five Honda CB750 engines. He also pioneered an after-market accessories industry, starting with four-into-one exhaust systems.

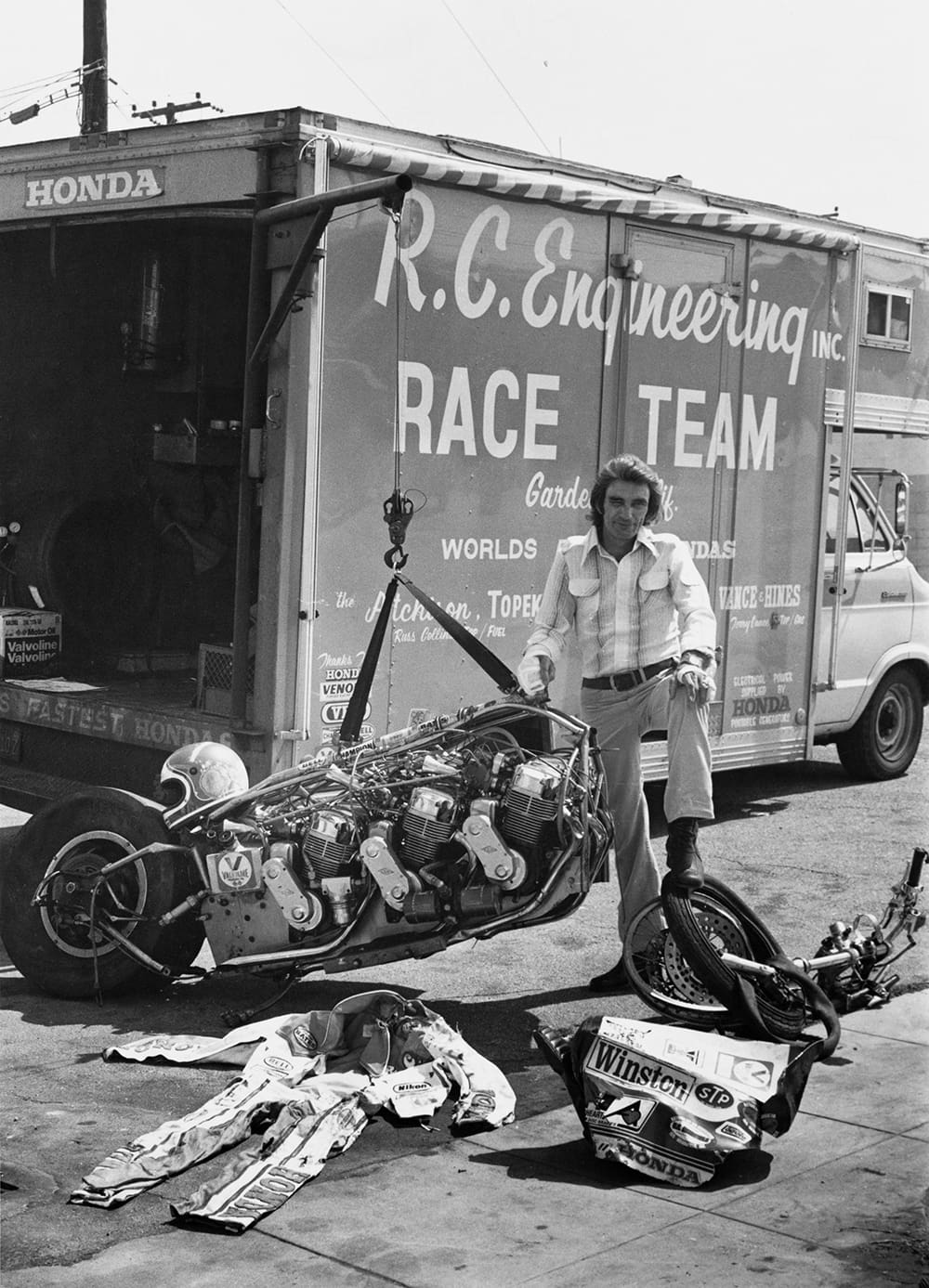

Collins first hit the big time in 1971 with the CB750-powered Assassin, a 163kg, 298kW (400hp) CB750. It was the first motorcycle to combine fuel injection and supercharging. He smashed his way into the Top Fuel class in 1973 with a triple-engined nitro-burning beast named Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, after the famous US railway line. It became the decade’s most iconic dragbike – being the first to cover the quarter mile in the seven-second bracket.

By 1976 it had run a best time of 7.80sec at 179.5mph (288km/h), but was destroyed in a crash that nearly killed its creator (see picture on the right). Collins bounced back in 1977 with The Sorcerer, an incredible feat of engineering that proved 200mph (321km/h) wasn’t a dream for a quarter-mile dragracer. Two 1000cc Honda engines were joined at the crankshafts to create a weirdo V8. The Sorcerer eventually ran 7.30sec at 199.55mph (321km/h), a record that stood for 11 years. Collins was always playing around with ideas, even building a five-engined effort he was photographed on for a publicity stunt (bottom).

He retired in 1980 and died from lung cancer in May 2014, aged 74. But father and son had restored the famous smashed-up Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe in 2012, so it lives to confirm the reality of the crazy 1970s.

Russ Jnr recently described his father as “taking drag racing from the dark ages of black leathers and oil leaks to something very sophisticated; a lot of maths involved and extreme leaps in technology”.

Hobbit from hell

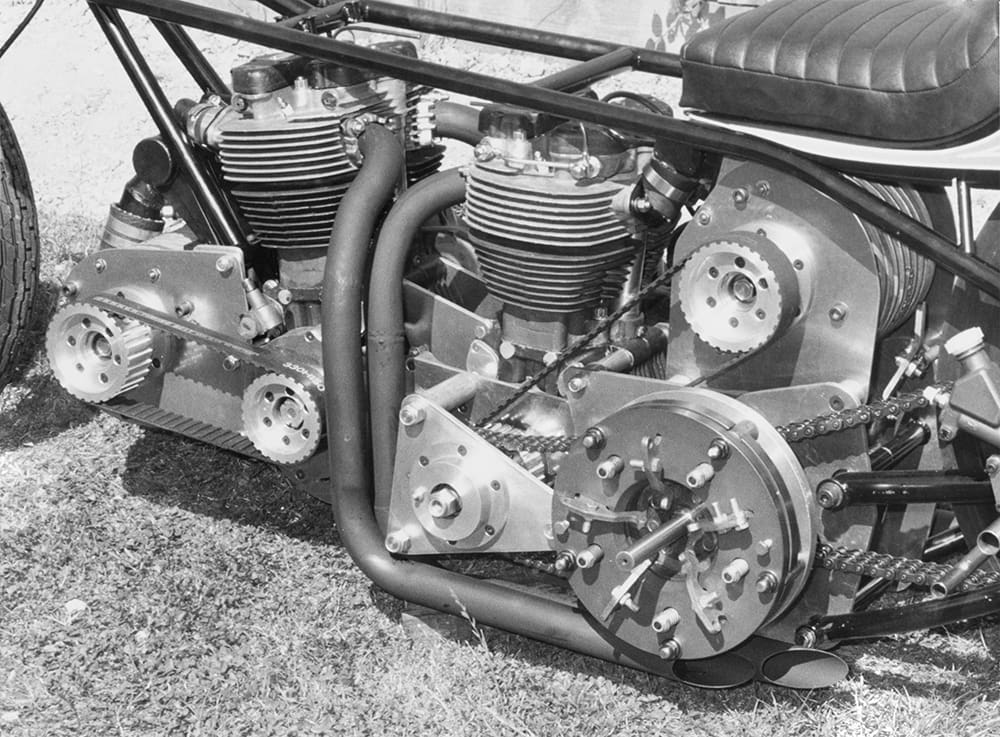

Filmmaker Peter Jackson was barely an itch in his old man’s underpants when Englishman John Hobbs started his fascination with drag racing. Back in the 1960s the Poms called it sprinting and George Brown and his supercharged Vincent Super Nero were the sport’s pioneers. Hobbs graduated through the usual procession of British twins until his Hobbit bellowed into life in 1975.

A collaboration between Hobbs, a motorcycle magazine and the Weslake engine company, its play-on-words name was chosen in a readers’ competition. Two supercharged, 850cc, eight-valve Weslake parallel-twin engines were joined in line by a series of gears. The engines ran on a diet of nitro-methane and methanol. It used a Crower Glide clutch (originally intended for a racecar) and power was transmitted through a two-speed auto overdrive unit. Rear drive consisted of a duplex chain turning a Minilite mag car wheel with an eight-inch M&H Racemaster slick tyre.

It sounds a bit crazy but, man, did it work. While there were a host of clever twin-cylinder twin-engined dragbikes in Europe and the UK, the Hobbit always seemed to steal their thunder.

Hobbs had some epic battles with Dutch Kawasaki importer and drag racer Henk Vink. One year Vink put up his Kawasaki Top Bike trophy to all-comers and the Hobbit took it. He also fronted US legend T.C. Christenson’s double-engined Norton Hogslayer in a famous shootout at the UK’s Santa Pod strip, but was blighted by handling issues. Later he discovered the huge torque of the engines had buckled the Hobbit’s frame. UK fans reckon Hobbs had built the ultimate British parallel twin. Fans of T.C. Christenson still disagree. The Hobbit evolved into a faster and faster fire-breather. By 1979 it was within a whisker of the seven-second Holy Grail. Nine seconds had been the benchmark at the start of the decade. Crazy how fast a decade can pass you by on the quarter mile.

The Hobbit won numerous UK and European championships with a best result of 8.07 secs at 168.9mph (271km/h) in 1979.

Hobbs retired that year, but over the past two decades has brought the Hobbit out for the occasional 160mph (257km/h) demonstration run at motorcycle festivals.

Feet-first funny bike

Is it a car? Is it a motorcycle? Some people say it’s neither – but the radical feet-first Quasar certainly got heads turning in the mid-1970s. A clean-sheet approach to personal transportation, it actually went into limited production after favourable press tests. Then the world forgot about it (until BMW’s C1 scooter and the Swiss MonoTracer were born two decades later). It’s proof that crazy ideas can live on in other people’s minds.

The brainchild of UK technical tinkerers Malcolm Newell and Ken Leaman, the Quasar’s design is based around a low centre of gravity (CoG). It was claimed this would give more stable handling than a conventional motorcycle, while the bodywork would increase protection. A beneficial side-effect of the low CoG was better aerodynamics that helped performance and fuel economy.

Just as well as the Quasar was powered by a four-cylinder, shaft-drive engine from a Reliant. The car gearbox was fitted with a foot-change linkage that prevented reverse gear being used. It had a leading-link front fork and a motorcycle swingarm and wheels. The rider sat on a hammock-like seat that could be adjusted for length to suit a preferred riding position. You’d think all this was craziness verging on stupidity – but bike journos were enthusiastic. They pointed out its upsides; weather and crash protection, and excellent high-speed stability. Its downside was a large turning circle and the rider having to put a foot out of the cabin as the Quasar came to a stop. There was no room for a passenger.

Newell did a brilliant job garnering publicity for the concept and the first production Quasar was built in 1976. Demand far exceeded supply and only 21 Reliant-engined versions were built in a sadly underfunded effort. The concept was developed haphazardly in the 1980s with a roofless version powered by various motorcycle engines and using hub-centre steering. Newell was working on a leaning trike similar to the later Piaggio MP3 when he died suddenly in 1994 aged 54.

Story Hamish Cooper Photography Getty Images & AMCN archives