The world’s first 24-hour motorcycle race, the Bol d’Or, celebrates its 100th anniversary at the 85th running of the event this weekend.

It was after the 1919 bicycle Bol d’Or, that the president of the Association of Former Military Motorcyclists (AFMM), Eugene Mauve, began thinking about a motorcycle version. Most members of the AFMM were World War I dispatch riders, keen participators in motorcycle events and, like many veterans, had difficulty picking up civilian life after the atrocities of the Great War.

To attract as many paying spectators and entrants as possible, Mauve wanted a short-distance track consisting of public roads close to Paris, and preferably out of town. Aimed at amateurs – though he wouldn’t say no to paying professionals on specialist machinery – the 24-hour race was opened up to entries of one rider per motorcycle.

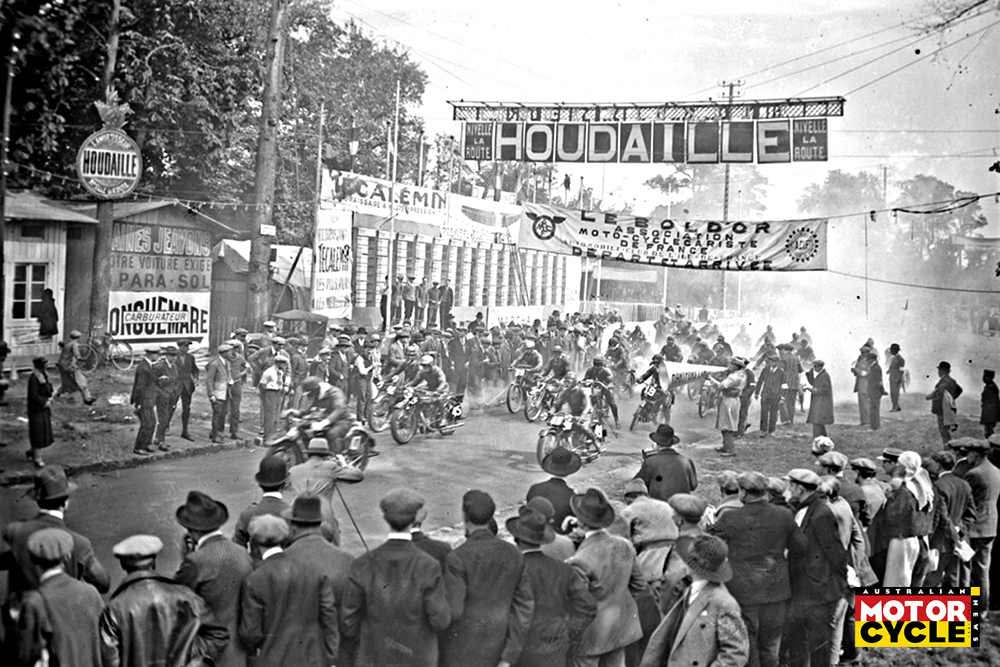

Mauve found a suitable location northeast of Paris, south of where Charles De Gaulle airport sits today. Several clay roads connecting the towns of Livry-Gargan, Vaujours, Coubron and Clichy-sous-Bois made up the so-called Vaujours Circuit which measured 5.126km. The first edition of the Bol d’Or 24 Hour took place over 27-29 May, 1922. There were two 24-hour races; the first, a motorcycle race, ran from 6.30am Saturday to 6.30am Sunday. The second, for for sidecars and cyclecars, ran from 8.30am Sunday through to 8.30am the following morning.

Both race categories shared the same rules. An average speed of 30km/h had to be maintained during the first three hours. Riders were entitled to four hours of rest during the 24-hour period, if they so desired, taken in one-hour increments. And while the motorcycle category was a solo race, the sidecars and cyclecar riders had a choice of either riding with a passenger/mechanic or with 60kg of ballast.

A total of 17 motorcycles started that first race, divided into four classes: bicycles with an engine, plus the three motorcycle categories of 250cc, 350cc and 500cc. As well as an overall winner, the winner of each class was determined by the rider who covered the longest distance during the 24-hour period.

The first-ever overall Bol d’Or winner was Tony Zind on a 500cc Motosacoche V-twin. He covered 1245.628km with an average speed of 51.9km/h. Second was Henry Naas on a 500cc Gnome & Rhône (1148.224km) and third was François Clech (1117.498 km) on a Motosolo. Clech also won the 250cc class, while a rider entered simply as ‘Laurent’ won the 350cc category with seventh overall. Just four of the 17 starters failed to see the finish.

A total of 12 sidecars and 23 cyclecars made up the field in the second race. The sidecar and cyclecar race was won by André Morel with a 1100cc Amilcar cyclecar (1450.658 km, 60.447km/h), while the first sidecar home was steered by Swiss rider Ed Gex on a 1000cc Motosacoche – he finished eighth overall (1153.350 km, 48.056km/h). Of the 35 starters, a total of 17 riders (six sidecars and 11 cyclecars) abandoned the race.

The first edition attracted 23,000 spectators, many of who complained about the lack of off-track entertainment once the monotony of a long-distance endurance race had set in. It was dusty, hot and the traffic congestion getting to the circuit put many people off returning.

So the following year it was moved to the 5.8km-long ‘Les Loges’ circuit, a small triangle of roads that ran clockwise around the forest of St. Germain. Two roads were paved, the third one wasn’t and had some potholed sections which Mauve figured would add a bit of interest. He also reformed the AFMM into the Association Moto-Cyclecariste de France (AMCF), which went on to become France’s biggest race promoter, and combined the motorcycles and sidecars, making the cyclecar race a separate event.

In 1924, the Le Mans starting procedure was introduced and by 1926, the the Bol d’Or had grown into one of France’s best attended events, with as many as 70,000 spectators enjoying what was now a carnival-like atmosphere.

Following the death of a spectator in the early stages of the 1926 race, the event was moved to the Circuit de l’Obélisque near Fontainebleau for 1927, but returned to Saint-Germain-en-l’Haye there following year, albeit to a shortened 4.18km version called Circuit de la Ville, where it remained until 1936. Though as entry numbers grew to as many as 90 starters, and technology and top speeds began to increase, Bol d’Or needed a permanent home.

The 5km inner circuit of the Autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry was chosen, but things didn’t exactly go to plan. The race was now run by an independant organisation which was said to be favouring AMCF riders, and led to a boycott; only 19 of the 47 entrants showed up. On top of that, Parisian party-goers found the new location too far to travel and spectator numbers dropped off a cliff. Not that the ones who were there had a lot to get excited about – only 10 riders actually finished and most of them took advantage of the four hours of rest.

The winner covered 1889.4km, beating French Norton rider Gustave Lefèvre – who would go on to become one of the event’s two most successful Bol d’Or riders with seven victories between 1947 and 1957. Norton is the event’s most successful non-Japanese manufacturer to date, scoring nine victories between 1935 and 1959. Suzuki is the most successful overall (18 victories between 1980 and 2021), followed by Honda (17 between 1969 and 2018) and Kawasaki (11 between 1974 and 2015).

WWII and its aftermath put a hold on Bol d’Or between 1940 and 1946. But in 1947 it was back, this time at the popular Saint-German-en-Laye circuit and it’s where Lefèvre took his first of his seven wins. In 1949 the race was moved again to Monthléry where it would remain until 1960.

The post-war races saw an influx of more modern machinery, and British machines entered the race in bigger numbers; brands like Matchless, Triumph and Velocette joined the mainland European brands like BMW, DKW, Moto Guzzi and Jawa. In the 1950s, and ultimately to its detriment, more and more racing classes were added to the Bol d’Or schedule – some years there was almost a 50 percent chance for every team to score a class victory. It didn’t make the racing more exciting, quite the opposite in fact, and sometimes riders simply stopped racing during the night to sleep. Visitor numbers dwindled and the once-famous Bol d’Or slowly but surely packed into insignificance.

After 1960 the organizers called it quits for almost a decade. The Bol d’Or had lost its appeal and the organisers decided not to host it again in 1961. That hiatus would last until September 1969. Because by then the world had changed and a new racing class, the Formula 750, had emerged. In those changing times, the Bol d’Or would also re-emerge – but only for French riders. And two 19-year-olds, Michel Rougerie and Daniel Urdich, rode a Honda CR750 works machine – the race version of the hugely successful CB750 Four – to first place. It wasn’t an easy win, mind you, the competition from the Kawasaki 500cc two-strokes was more than fierce, but Rougerie and Urdich covered 2803km on their way to victory, at an average speed of 116.609km/h.

The 1970 Bol d’Or was open to all nationalities, and the last time the 24-hour event would be held at Monthléry. History was written when Tom Dickie and Paul Smart rode a Triumph 750 works triple to a new record of 2959.3km at an average speed of 123.201km/h. Up until that point, European brands had dominated the event, but this would soon change. In 1971, with the race now moved to famous Bugatti Circuit in Le Mans, Ray Pickrell and Percy Tait won the 35th Bol d’Or with a BSA 750cc triple with a 2723.95km race averaging 113.495 km/h. Augusto Bretttoni and Sergio Angliolini on a Laverda SFC750 finished only seven laps behind, with Vittorio Brambilla and Guido Mandracci another four laps behind them riding a a prototype V7 Sport racer with a capacity of 850cc. Guzzi was thrilled and went on to baptise its 1975 850cc sports range ‘Le Mans’ as a result.

After 1971 the Japanese factories dominated the Bol d’Or. Japauto emerged as a forceful team with its 950 Honda-based four and were the victors in 1972. Gérard Debrock and Roger Ruiz won ahead of the French pairing of Georges Godier and Swiss rider Alain Genoud on an Egli-Honda 750. John Williams and Stanley Woods finished third with their Honda 750.

The 1973 event was held in relentless and torrential downpour, but Gérard Debrock and Thierry Tchernine rode the Japauto 969 to victory, averaging 115.172km/h in 24 hours of racing. The 1974 and 1975 Bol d’Or races were dominated by Georges Godier and Alain Genoud on Egli- and Donques-framed Kawasaki endurance racers.

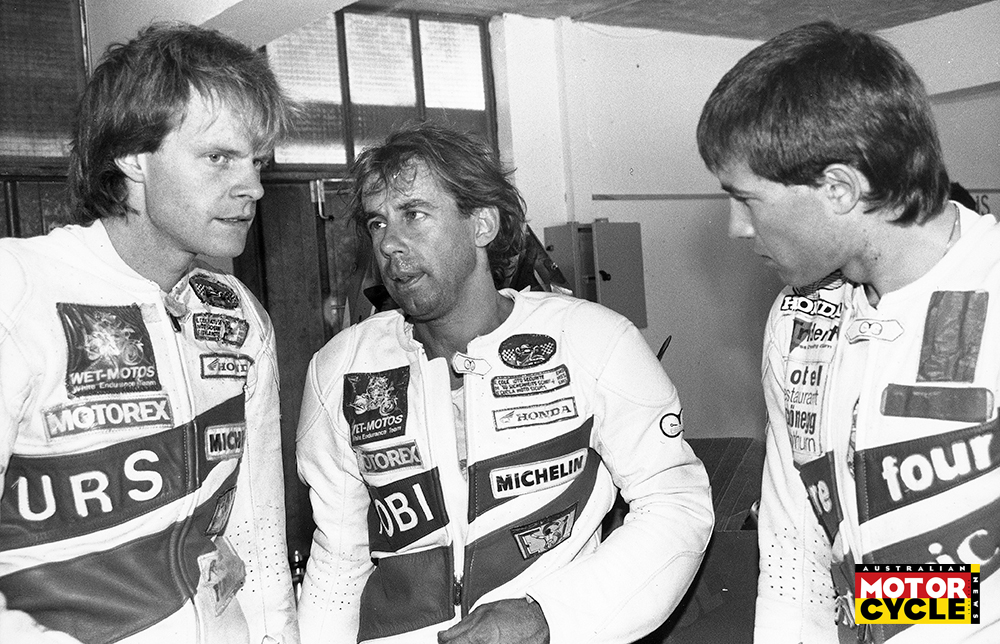

Honda wasn’t pleased with the Kawasaki success and unleashed its RCB1000 for the 1976 endurance season. A race-long battle emerged in the Bol d’Or that year. Not even five Kawasaki teams –made up of Jacques Luc and Alain Vial, Christian Sarron and Denis Boulom, Michel Frutschi and Georges Fougeray, as well as Jean-Francois Balde and Yvon DuHamel– could not prevent RCB1000 riders Jean-Claude Chemarin and Alex George from winning the race.

Incredibly, their race-winning distance was the first time more than 3000km was covered during a 24-hour race and the pair smashed it, averaging 134.797km/h to cover 3235.125km by race end. They backed it up with another victory in 1977 and year later repeated their success, but this time on the 5.809km Circuit Paul Ricard where the event remained until 1999. From 2000 to 2015, Magny-Cours played host to the iconic 24-hour race, before returning to Paul Ricard where it remains today.

The 1970s was an era where endurance racing saw an influx of hugely innovative and purpose-built racing machines. Hub-steering, space frames, single-sided swingarms and experiments with aerodynamics and frame technology lead to a more than interesting decade. This quickly ended, however, when the series received world championship status in 1980.

More than before, endurance racing then became even more professional and a hunting ground for Japanese factory teams with incredible budgets. The current Bol d’Or event is in enormous contrast to its humble beginnings of 1922. But it is still is a race where determined amateur teams can take it to the might of the factory outfits, and still against a backdrop of 24-hour entertainment.