The New Zealand-built Britten V1000 shocked the motorcycle world in 1992 with its innovative design. And while it was only eligible to race in niche events, such as Battle of the Twins and BEARS events, it made a legend of its creator, John Britten.

As well as setting world land speed records in 1994, it was featured in the New York Guggenheim Museum’s ground-breaking The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition in 1998. Britten’s creation really was performance art.

Many people think John Britten built his bike alone. The truth is this charismatic Kiwi free-thinker surrounded himself with like-minded enthusiasts. They were hugely talented and freely donated their time in a project that embraced all aspects of motorcycle manufacture. Once built, the next mission was to find riders brave enough to test untried designs on the world’s fastest and most dangerous circuits.

Two decades on, some of the most significant Britten riders share their thoughts.

The original racer

Gary Goodfellow

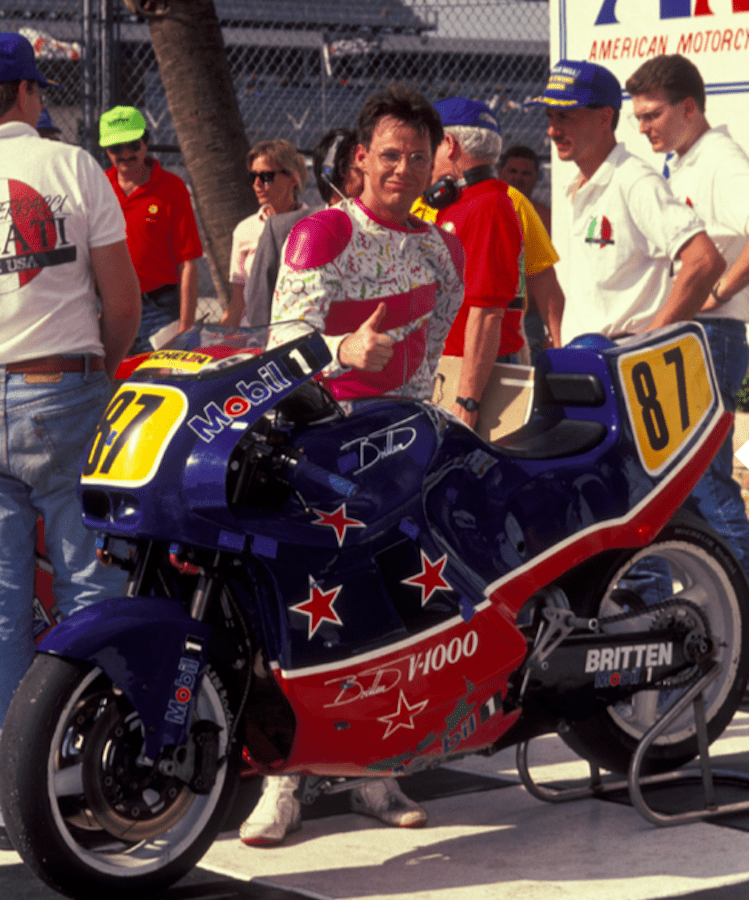

Often overlooked in the history of the Britten, Canadian-based Kiwi Gary Goodfellow was the rider who first gave the project credibility.

He started out racing Aero-D-One before moving onto the Precursor, which he took to Canada to develop.

“Aero-D-One was running on alcohol so it had impressive power, but it also seemed to handle pretty good off the bat,” he recalls.

“I only rode it for about three months because John goes, ‘Oh well, that’s no good so I’ll build a new one.’ ”

That was the Precursor.

“I did the development riding and then raced it in Japan, Canada, USA, NZ, Europe, all around the world really.

“It handled amazingly well. I can compare it to a period superbike, like an RC30 or GSXR750. It was a little bit more nimble, it had lots of power and good grunt, and handled fantastic with White Power suspension.

“John was a fun-loving guy – he was 100mph. He only had 45 years of his life but he fitted 90 years into those 45.”

Gary, along with several members of the original team, still believes the Precusor would have been relatively easy to put into limited production, as Bimota was doing at the time.

The young gun

Chris Haldane

A teenager in a hurry, Chris Haldane was hungry to ride any competitive motorcycle. He became one of the few to race both a Britten V1000 and a Precursor.

Haldane recalls: “At that stage the bike had White Power suspension and conventional forks and it was very light. It was one of the best handling bikes I’ve even ridden. There were issues with tuning and sheared primary gears, and it actually broke the rear suspension during a race, tossing me off on the sweeper! But on the whole it was pretty impressive. We won quite a few races.”

Haldane was also involved early on with the V1000.

“It did a few funny things, like under hard braking it used to do this little weave (Chris moves his hands from side to side). The front felt almost like the steering head bearings were seized or something like that.

“The bike always felt like it never had much weight transfer, like the front sat quite high all the time. It wasn’t like a conventional bike where you get all that good feeling of the suspension loading the tyre up.”

Haldane returned in 1998 for a test and one-off race in Japan on one of the last customer Brittens.

“It was more refined, it handled better, it stopped better. All the problems had been fixed.”

The Daytona specialist

Paul Lewis

As the Precusor project gained momentum, John Britten started a process of hiring high-profile international riders.

The first was ex-500cc GP racer Aussie Paul Lewis, who rode the much developed Precusor to second place at Daytona in 1991.

“In practice we had some issues, with fuelling and stuff, but the bike was awesome, really stable,” Lewis recalls. “We were racing against Doug Polen on the factory Ducati 888 he’d used to win that year’s World Superbike championship! Steve Crevier and I qualified on the front row, we took off and I took the lead dicing with Polen.

“Steve broke down on the first or second lap and it was just me and Doug, and we were flying. About lap three I had an issue with the fuelling. At part throttle through the corners it would go onto one cylinder. If I wound the throttle right out the problem stopped. It was a big battle but I finished second.”

Legend on a legend

Nick Jefferies

Nick Jefferies had won the 1993 Formula One Isle of Man TT for Honda, but switched to the Britten V1000 after seeing Shaun Harris on it that year. Few people had more IoM experience than Nick so he was a great choice.

Jefferies rode the Britten at the 1994 North West 200, the Isle of Man TT and at Donington in a British championship race.

He recalls: “We had three brand new bikes to ride at the Isle of Man, which proved to be a disaster as they were under-developed and not tested. We had trouble getting a lap in.

“The Britten was easy to ride and if I had the opportunity to get confidence on the bike I could have concentrated on getting it around the TT course fast rather than just riding it as if it was about to break – which was the way we ended up riding them. Sadly, I didn’t finish either the Formula One or the Senior.”

The world champion

Andrew Stroud

The most famous and successful Britten racer of all is Andrew Stroud, who won the 1995 world BEARS title on the V1000. He also won the major international Battle of the Twins races at Assen Holland, and Daytona four years in a row (1994, ’95, ’96 and ’97) along with two New Zealand championships.

“I rode all of the V1000 Brittens except for the last one, number 10,” Stroud says. “The Britten always struggled with the front end in mid-corner, when it would shudder a little bit. It had its advantages, because I could control how much dive I had under brakes; we just changed the eccentrics on the wishbones. You could set it up so when you hit the brakes it didn’t dive at all, but I had it so there would be 10 or 20 per cent of suspension left turning into corners under full braking to absorb any bumps – where usually telescopic forks were already bottomed out. So that was a potential advantage.

“At first the V1000 was slow to change direction so we cut about 5kg off the crankshaft. This made it spin up more unpredictably, but made it change direction faster and helped it turn in better. The Britten didn’t feel that nice in the corners, but you could still get around them quite fast!

“It had lots of low-down power, more traction than a four-cylinder bike, and it gripped pretty good.”

Rev it up!

Jason McEwen

Jason McEwen rode the V1000 for two seasons in NZ, and won the 1994 NZ championship against stiff opposition.

McEwen says: “It was sweet! It was bullet-proof. It had plenty of power everywhere and I could rev the date off it! That was one of the things I helped with. It only used to rev to about 11,000rpm. I’d ridden Ducatis before and I knew it needed to be revved – it was saying to me, ‘Don’t you change gear yet’. John didn’t know about it initially so I had a word with the mechanic and he got on the computer and upped it to 12,000rpm. I went about a second and a half a lap quicker straight away with the extra horsepower. Eventually we put the rev range up to 12,500rpm.

“We also had a five-valve motor with slightly different fuel injection. It didn’t quite have the top-end power of the four-valve motor.

Second to none

Stephen Briggs

Stephen Briggs raced the CR&S Britten in Europe from 1995 to early 1996, and then for the 1996/97 NZ summer season. Briggs was second to Stroud in the 1995 world BEARS championship.

“It was all about the engine – the engine was just fantastic! It had so many shortcomings in the handling department. It wasn’t until I stopped riding the Britten that I realised I had had to change my whole riding style to adapt to the bike,” Briggs says.

“It had major chatter and patter problems. Some tracks it was fine, and some tracks it was so bad I literally had to deal with it on the day and try not to keep the corner speed too high, because once it started chattering, it was like a frequency that would go through the bike. It would start at the front and midway through the corner the back would be chattering as well!

“The faster they made the engine the more difficult the Britten became to ride. As soon as they introduced the slipper clutch the chattering diminished to a point where it was acceptable.”

TT tough guy

Shaun Harris

Two-time Isle of Man TT winner Shaun Harris raced two versions of the V1000 around the Mountain Course, and within Europe.

Harris was badly injured in a crash last year, but in an earlier interview he said: “Its exceptional thing was the power – that’s it. It handled very badly. You could watch Jason McEwen and Andrew Stroud ride it here in NZ, and it was just because they rode the wheels off it that it did so well. It was so damn fast compared to everything else.

“The front end was terrible, it pattered its face off all over the place because of the forks, lots and lots of reasons: the girder forks were too rigid, there was no flex, the swingarm angle was too low so it would squat, wheel stand, patter. Yeah, its forte was the motor really. Apart from the fact that it was a sexy looking bike!’ ”

What could have been

Nearing the end of its development, a second generation Britten was talked about.

Stephen Briggs explains: “Changes discussed included a bigger bore, a shorter stroke, better valve area, and we always struggled with cooling as the bike could only sit still for half a minute because the radiator was so small.

“Tim Stewart [factory technician] was worried because the throw of the crank really pushed the piston into the bore hard. Because the liner was only cast iron, with a set of brand new liners and pistons you only had 40 maybe 50 good laps before the power started deteriorating.

“The carbon fibre wheels looked really light but they weren’t, they were actually heavier than mag wheels because the carbon technology back then was so poor. Everything on the bike was made of steel – the exhaust system, the nuts and bolts. Using titanium could have made the V1000 8kg lighter.”

Know your Brittens

Aero-d-Zero

Ducati-powered special built by Mike Brosnan, with John Britten making the bodywork and swingarm.

Aero-D-One

Speedway-based, air-cooled Denco V-twin engine powered a special built by John Britten featuring a monocoque-type frame, White Power suspension and Marvic wheels.

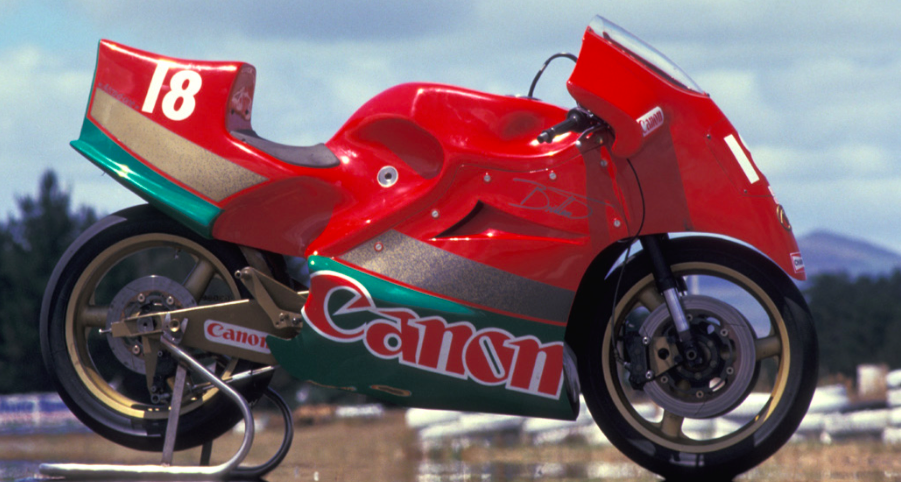

Precursor

Clean-sheet design employing Britten’s own fuel-injected, 60º, liquid-cooled V-twin engine and GP-spec suspension and brakes. In what would be a typical Britten modus operandi, the all-new bike was finished just in time for the annual BEARS Sound of Thunder meeting in 1989.

Over at Daytona, Gary Goodfellow led the pack into the first corner in the annual Battle of the Twins race, out-accelerating factory-supported Ducatis. Then the bike’s ignition cut out.

Back in New Zealand, John established Britten Motorcycles and the team built a second Precursor. The two bikes went to the 1990 Daytona meeting with riders Goodfellow and Robert Holden finishing strongly in the top 10.

After a year of development, Steve Crevier and Paul Lewis rode the bikes at Daytona in 1991 with Lewis coming second to Ducati ace Doug Polen.

The true potential of this Britten design was still coming to fruition when its creator moved to the ultimate Britten design.

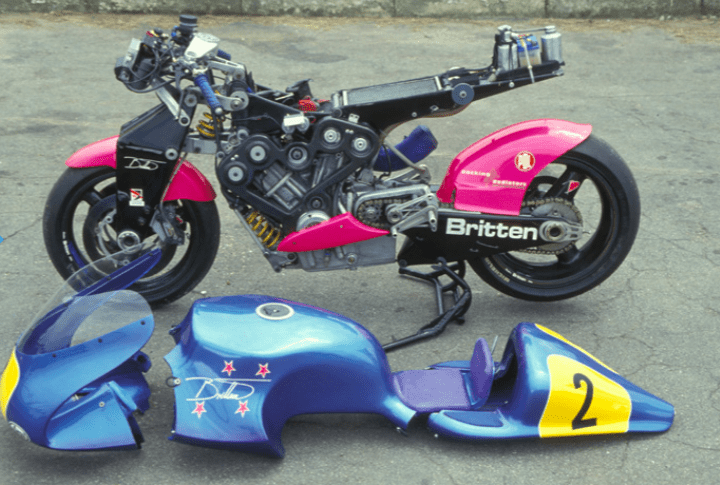

Britten V1100/V1000

With worldwide interest in his engine design from such companies as Bimota, Britten considered his options.

Rather than take the safe path of perfecting the Precursor and putting it into limited production he started again from scratch.

This time the entire project was built in-house. From the carbon-fibre wheels and wishbone-girder front forks to the programmable electronic engine-management system, no stone was left unturned.

The result stunned the motorcycling world on its debut in 1992.

A core design element was the way it harnessed the air it travelled through. Even with just a minimalist half-fairing the V1000 was consistently the fastest motorcycle at Daytona’s speedbowl and quicker than Honda’s RVF factory racers at the Isle of Man TT.

While its many victories in the support class of the Daytona 200 with rider Andrew Stroud built a reputation, its appearances at the Isle of Man TT really fired up mainstream support.

The bike first ran with Shaun Harris in 1993, then a three-bike team in 1994 that included top TT racers Nick Jefferies and Mark Farmer. It was a classic Kiwi fairytale of the little battlers taking on the big boys.

Sadly, the fairytale had a dark side, with Farmer’s fatal crash in a highside under acceleration at the Black Dub.

Then John Britten’s early death from cancer in 1995, just months after Andrew Stroud had won the inaugural World BEARS Championship with fellow Britten racer Steven Briggs second, again shocked New Zealand.

The company continued for a few more years, producing the limited-production run of 10 that John Britten had promised and achieving many more race successes.

The 10 Britten V1000 Racers

Of the 10 Britten V1000s built from 1992 until 1998, the ‘Cardinal V1100’ is the first of three ‘factory’ racers. The seven ‘customer’ racers start with the CR&S Roberto Crepaldi V1000 and end with the one now owned by Virgil Elings. Here they are listed in order of manufacture.

No 1: The 1100cc version which started the legend. The Britten family recently bought out original part-owner Cardinal Network’s 50 per cent share.

No 2: Factory racer No 2. World BEARS winner in 1995 and the Britten most associated with Andrew Stroud. Owned by Kevin Grant and has been in continuous use since its manufacture in 1992.

No 3: Factory racer No 3. Has been on display in New Zealand’s national museum Te Papa for over 20 years.

No 4: First customer V1000. Sold to Italian Roberto Crepaldi of CR&S, it is the most raced. Second place World BEARS in 1995 with rider Stephen Briggs. Also raced at the TT twice. Current owner are Americans Bob and Missy Robbins.

No 5: Displayed at Guggenheim Museum’s The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition in 1998, this second customer V1000 was a regular Daytona winner with Andrew Stroud. Owner Jim Hunter, US.

No 6: Ridden by Nick Jefferies at 1994 North West 200 and TT, the year Mark Farmer died on the CR&S Britten. Owner Dr Mark Stewart, US.

No 7: Owner George Barber, Barber Museum, US. One of the main attractions of the world’s largest motorcycle museum. Run regularly by technician-racer Chuck Huneycutt.

No 8: Originally sold to American Mike Canepa, whose team raced a Britten and Harley-Davidson VR1000. Painted harlequin lime/purple/green. Current owner is American land-speed record legend Charles Nearburg.

No 9: Won Daytona 1998. Raced in Japan by NZ Superbike champion Chris Haldane. Painted silver-gold for European events. Owner Gary Turner (proprietor of BST Wheels).

No 10: Last production Britten. Never raced but NZ Superbike champ Jason McEwen signed it off as test rider. Owner Virgil Elings, Solvang Vintage Motorcycle Museum, US (original owner Mike Iannuccilli).

WORDS TERRY STEVENSON & HAMISH COOPER PHOTOGRAPHY ALAN HURFORD, STEVE GREEN, CHRIS DE BEER AND TERRY STEVENSON