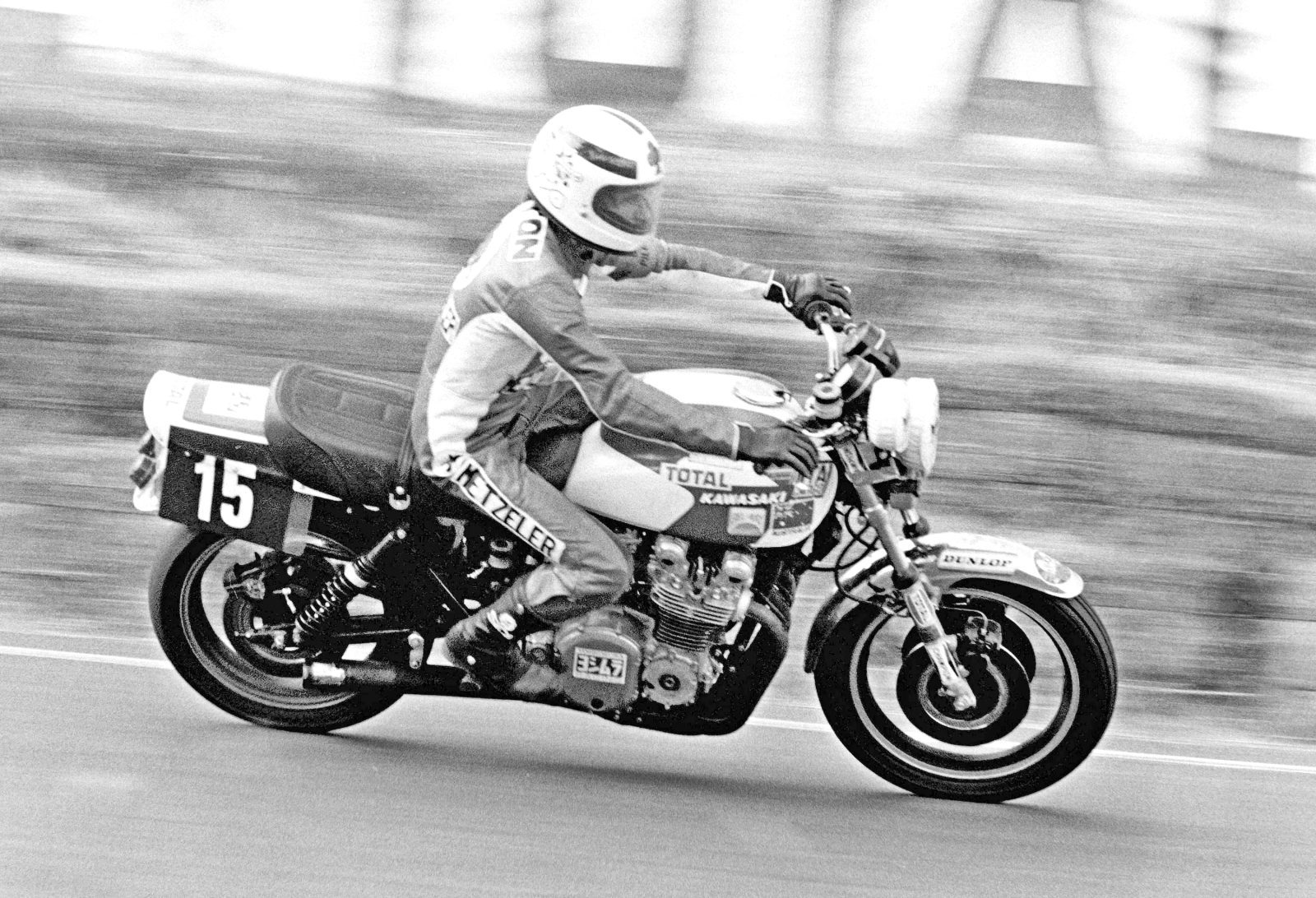

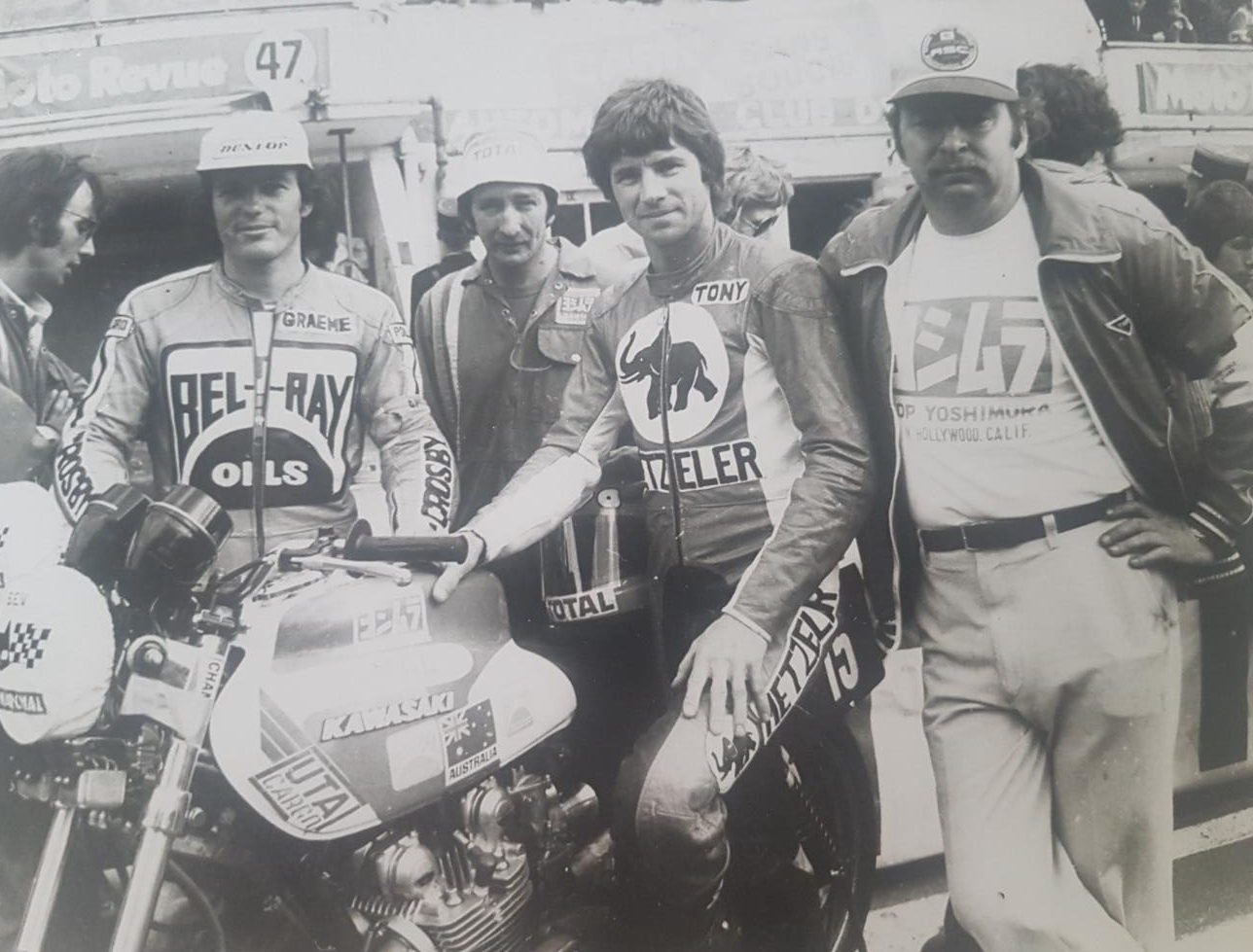

The day when Graeme Crosby and Tony Hatton should have won the iconic Bol d’Or 1977, 24 Hour – on a roadbike!

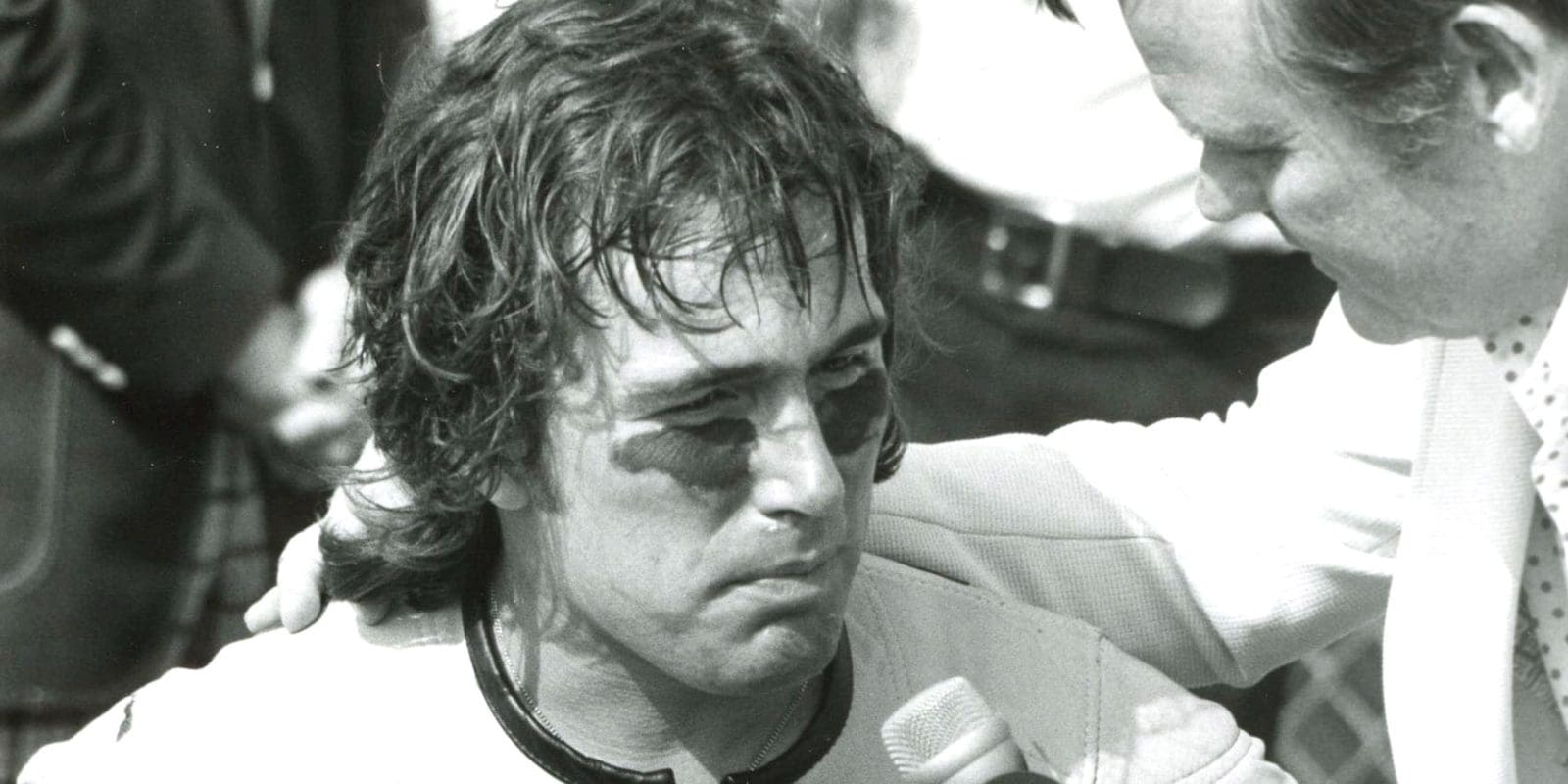

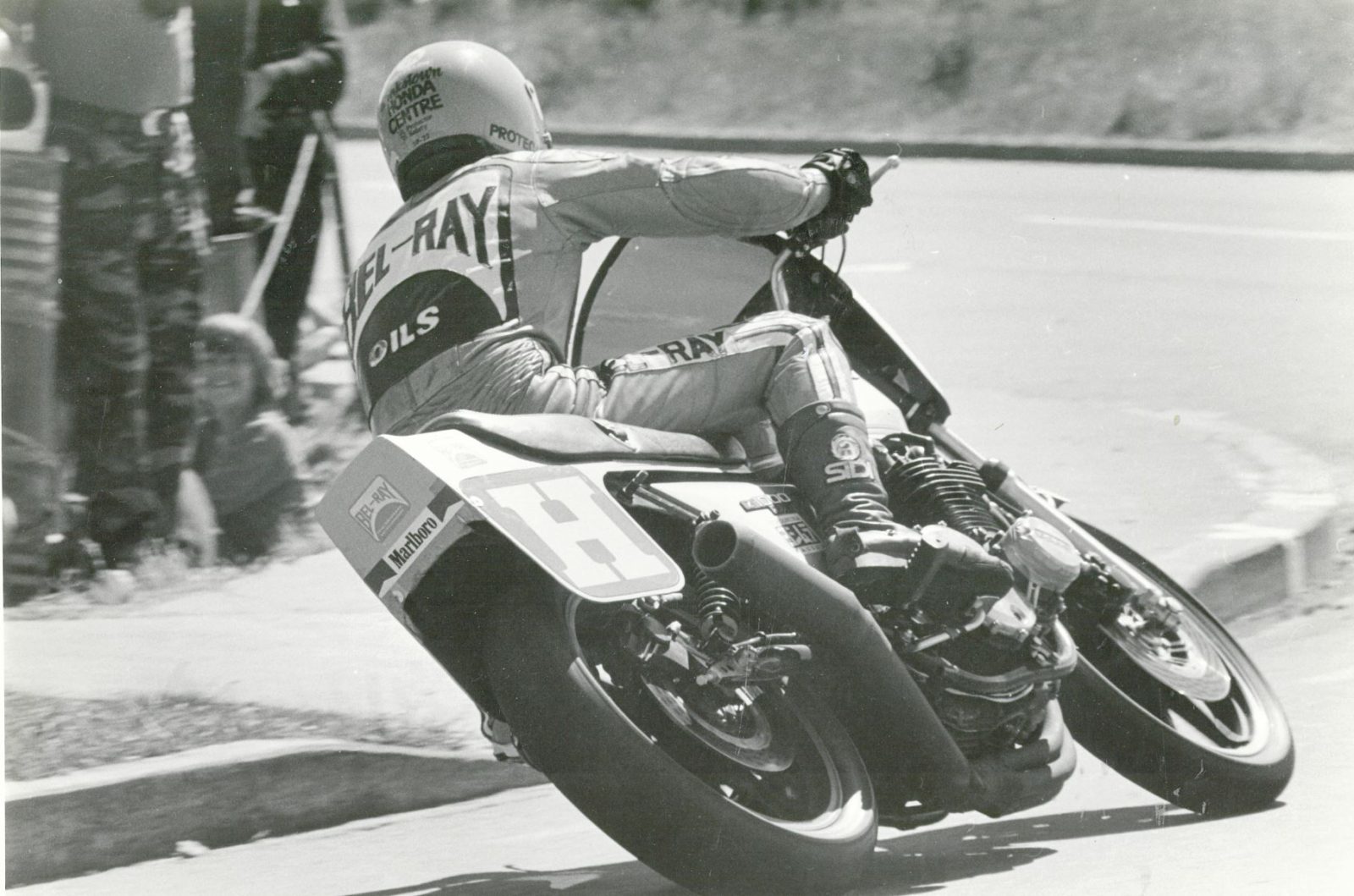

At 270km/h on a French country road, 22-year-old Graeme Crosby has a moment at a combined blind crest and right-hand kink.

“She got into a bit of a tank-slapper and I came over the crest on the left-hand side of the road. I forgot just for that moment and anything could have happened… a little old lady on a pushbike.”

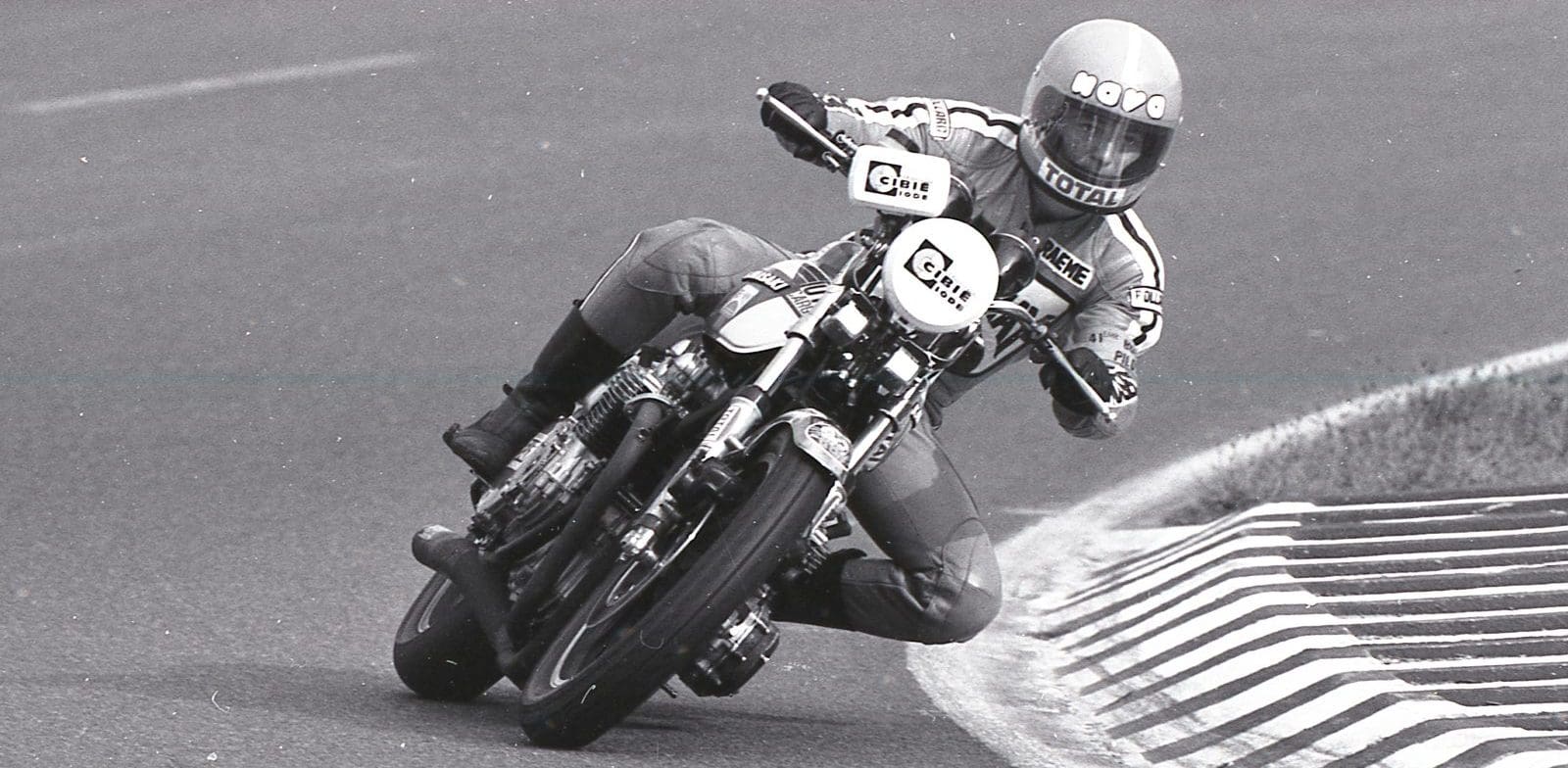

This was Croz describing one of several scary incidents in September 1977, when his sponsor Ross Hannan mounted an audacious assault on the world’s most famous motorcycle endurance race, the Bol d’Or, with a Kawasaki Z1000 Superbike. The road was Mulsanne Straight, a section of the famed Le Mans 24-Hour car-race circuit. Croz was running in the engine and helping sort the jetting.

It was Saturday, 17 September, 1977. Race start was 4pm that afternoon on the 4.2km Le Mans Bugatti Circuit, home of today’s French Grand Prix, minus the chicanes.

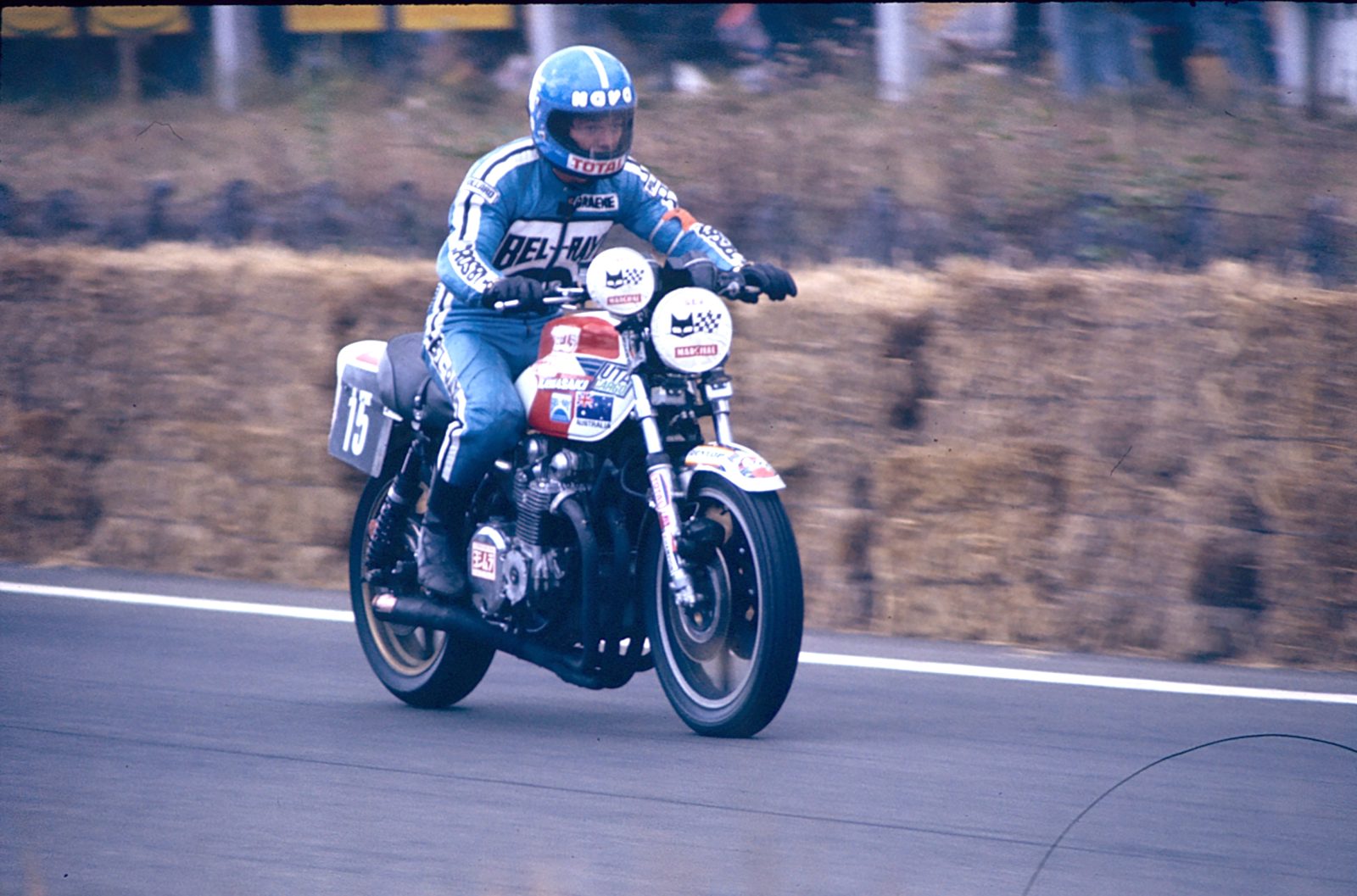

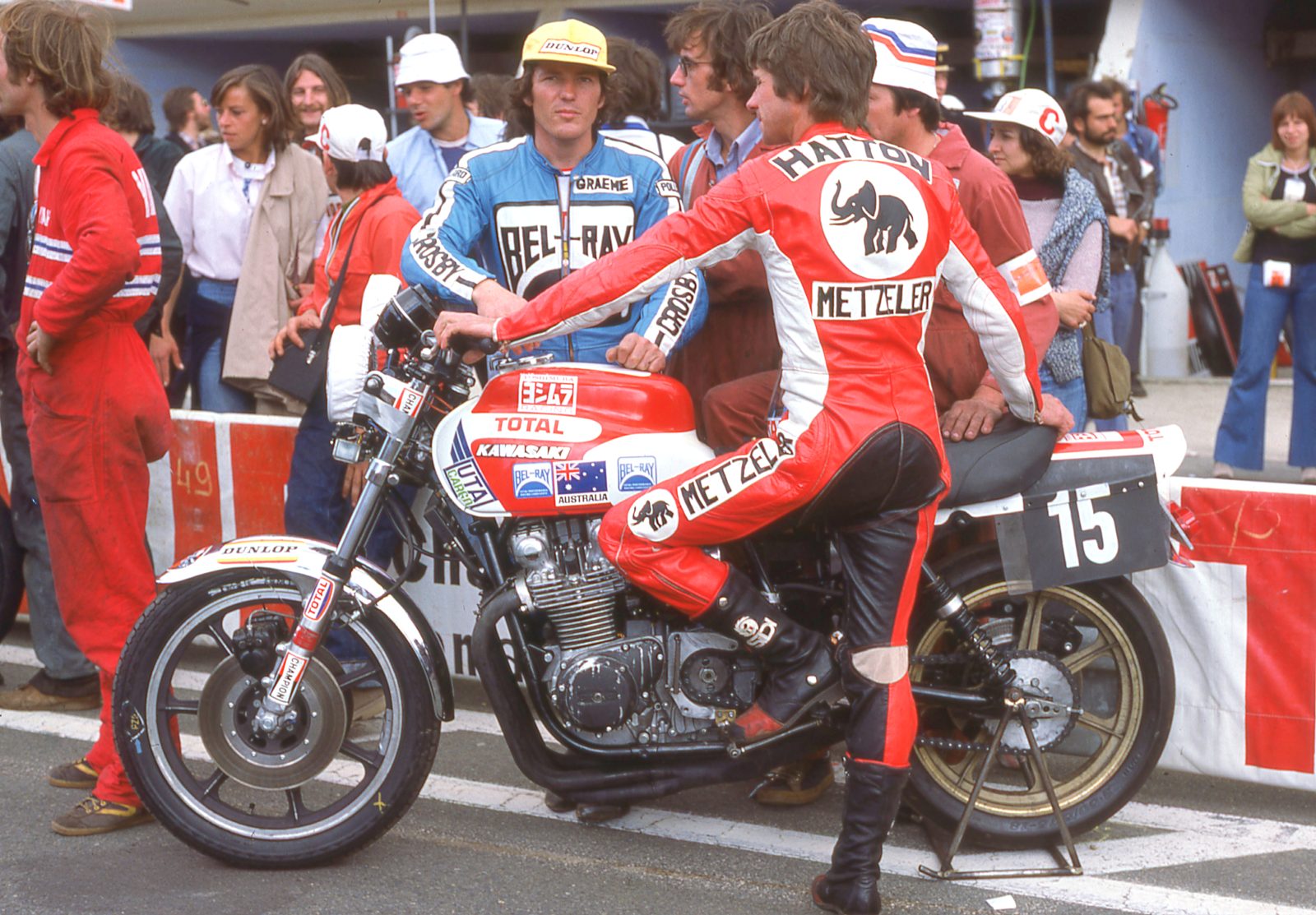

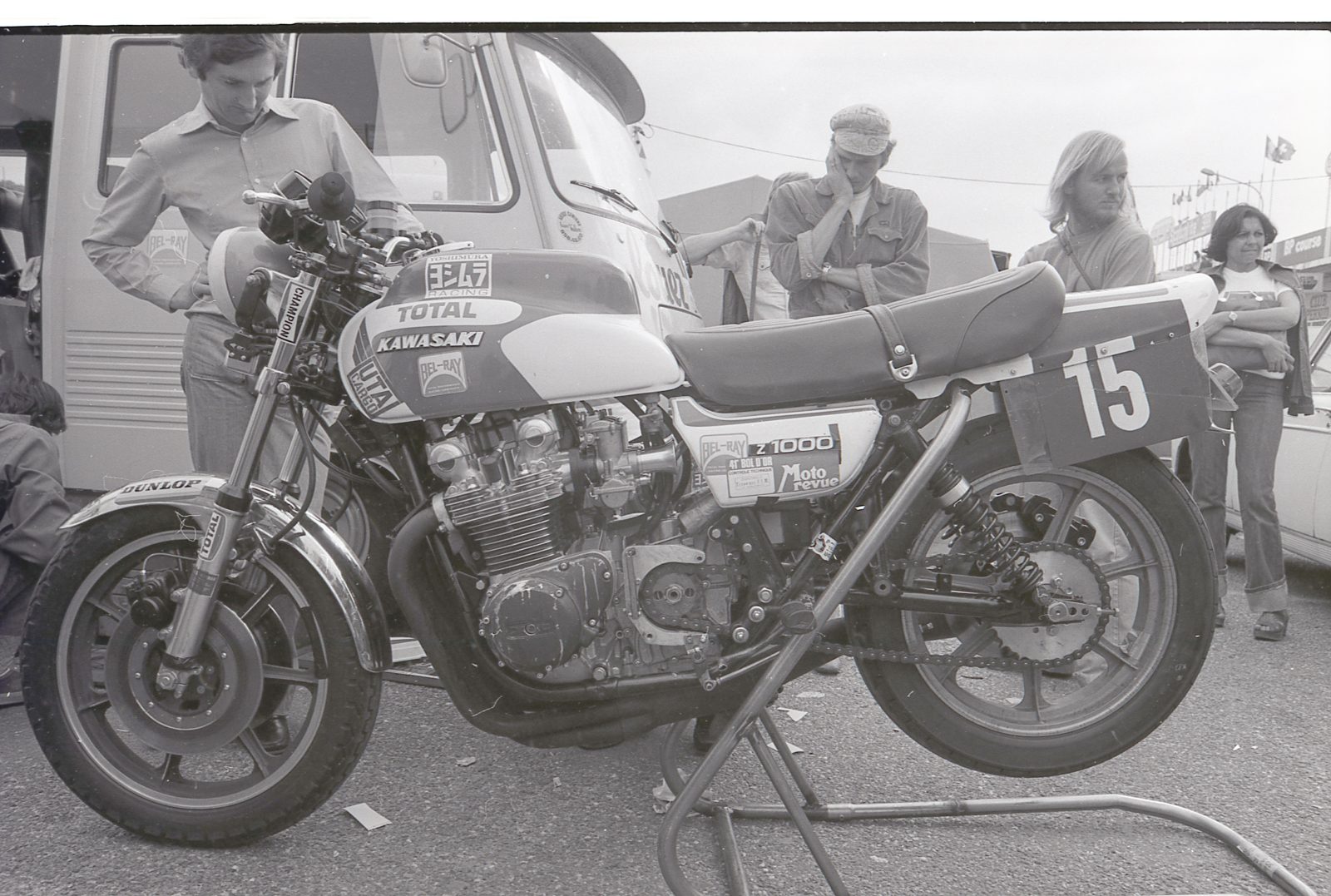

Crosby found himself in France as Hannan’s sponsored Superbike rider. Hannan’s inspiration was seeing a film of the Bol d’Or at a motorcycle club meeting back in Australia. He saw streamlined machines with prototype chassis, and engines tuned for economy. He wanted impact to promote his business and the Yoshimura tuning parts he imported with a muscular, naked Superbike. Crosby had been making waves in Australasia for the previous 12 months on one dubbed The Beast. Younger brother Ralph Hannan had, on Ross’s suggestion, moved from New Zealand to fettle it.

“My f…ing brother!” Ralph recalled in 2009. “He’s sitting around at home, doing nothing, then he comes into work and says we’re doing the Bol d’Or. ‘Ross, we’ve done Europe,’ I said.”

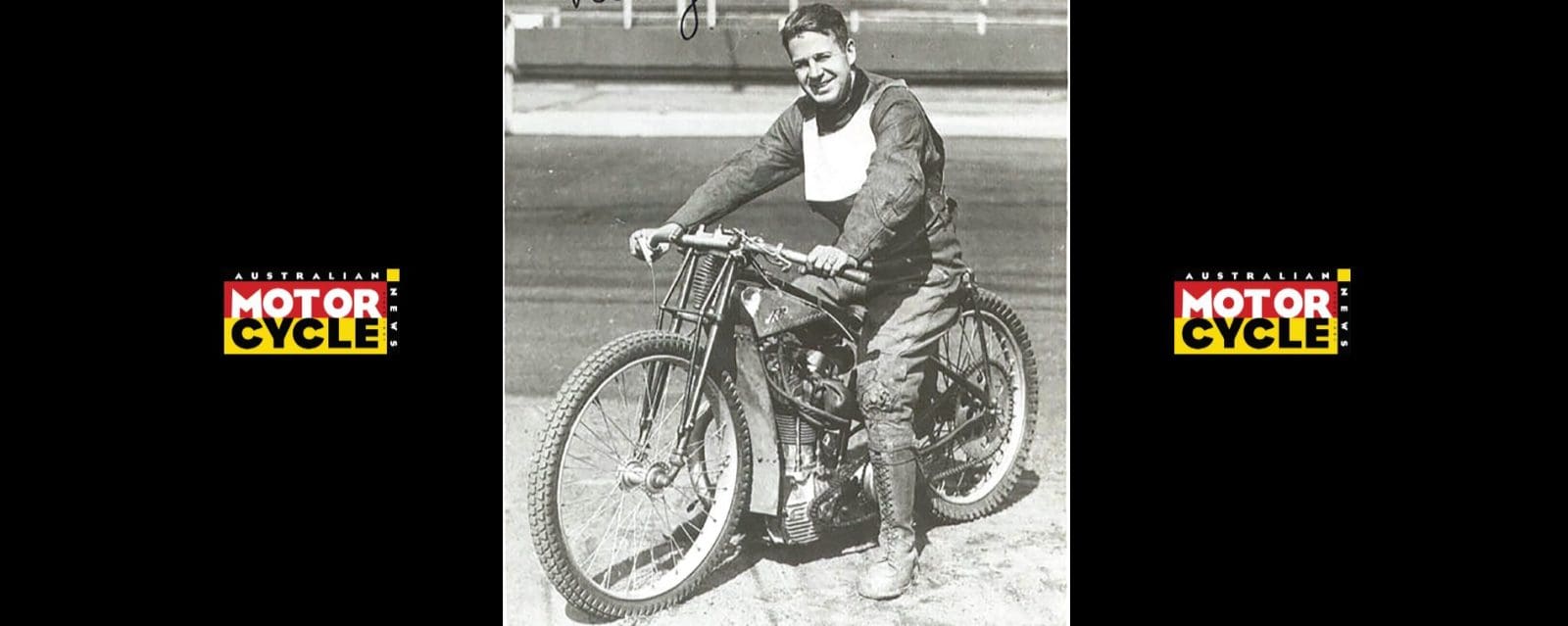

And so they had. Ross in 1969-70 until he was run over by several bikes early in a mass-start practice session at the Isle of Man and Ralph in 1968-70 as mechanic for Ross’s brother-in-law Terry Dennehy and New Zealand’s Ginger Molloy. Ralph had been a keen surfer until Ross distracted him with motorcycles. He lived and raced in New Zealand in the early 1970s, working at Molloy’s motorcycle shop.

In 1976, Ross commissioned Ian Cork to turn his race-crash-damaged Kawasaki Z900 roadster into a Superbike. On Ralph’s recommendation, he gave the ride and a job to Crosby, who had twice won the NZ 6 Hour Production Race solo. At Hannan’s shop, in the inner Sydney suburb of Camperdown, he ported cylinder heads and appeared in advertising as “our factory-trained mechanic”. For around $1150 customers could have a 130 horsepower Kawasaki.

Ross Hannan and David Dixon in the UK were on a similar mission. At one point, they mortgaged their respective houses to keep Yoshimura’s business afloat. The Hannans were now working against time to build a racebike in two weeks. They also had to devise a lighting system and test it. Ross secured sponsorship for airfares, freight, fuel, oil and lights. He found limited trade support but some sponsorships fell through.

The lighting system was tricky. Ross reckoned a Kawasaki alternator would not cope with sustained high revs. Instead, he pumped for Cibie driving lights run from a battery. “We would have to refuel every hour, so we could swap batteries every hour,” he said. That decision would come back to haunt them. “And Ralph has never let me forget that.”

Another question was who would ride with Crosby. One suggestion was Murray Sayle of Team Kawasaki Australia. The eventual choice was Tony Hatton, the guy who had crashed Ross’s Z900 at the Adelaide 3 Hour.

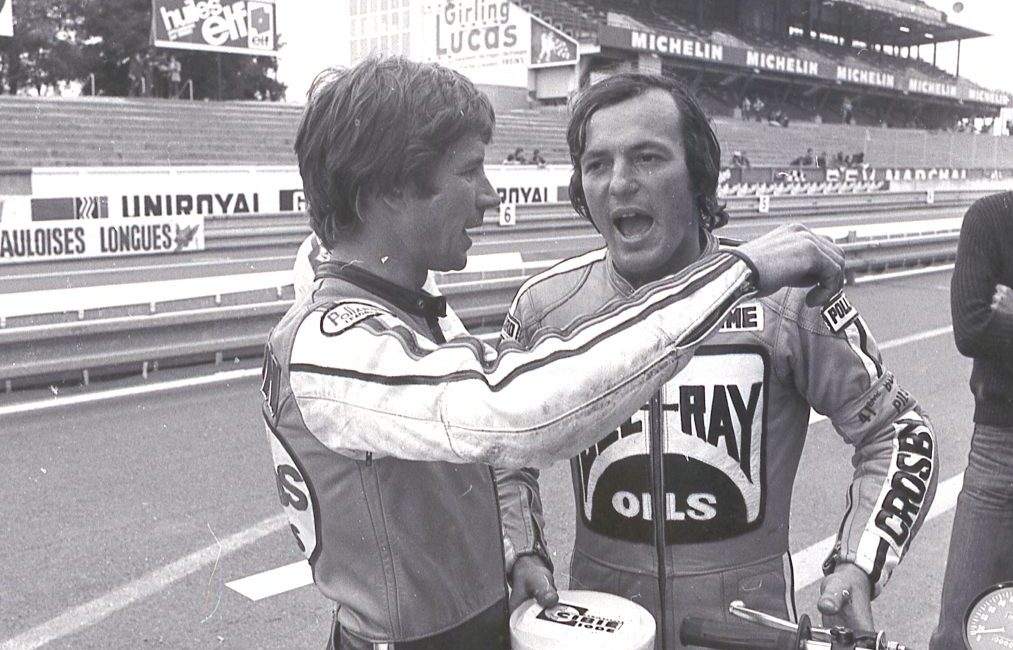

Hatton was an icon as a rider’s rider, mentor and for race-bike prep. He proved the perfect foil for Crosby, knowing he was far more race wise than his age or larrikin streak suggested. He could, as Hatton observed, ride a bike right to the limit of its capabilities and not step off. It was Hatton’s belief that Crosby was already a better rider than Sonauto Yamaha pair Patrick Pons and Christian Sarron.

“Everyone who hadn’t met Croz thought he was a clown,” he said. “They’d see him go fast and try to match him. Soon they’d crash and come back in band aids. Sometimes when I rode with him I was two seconds a lap slower, but I was proud if I could finish the race.”

The Hannan team did a night test on the lighting system at Oran Park and headed to France… Ross and Ralph Hannan, Crosby, Hatton, Metzeler tyre importer John Galvin, Peter Brenigan from New Zealand, Greg Davis from Melbourne, John Frazer an engineer friend of Ross and a photographer friend of Hatton – ‘Team Australia’.

Ralph remembers. “We were limited with what we could take over on an aircraft. I just packed the stuff in a bag and took it with me.”

First drama. They flew into Paris’ Charles de Gaulle Airport, but UTA’s air cargo division lost the bike for three days. It was Thursday, 15 September before they had it and the team transporter was a nine-seat Peugeot wagon. Crosby was detailed to ride the bike on public roads via Paris some 240km to Le Mans. This would double as running in one of their two engines.

Crosby wondered what he had done to draw the short straw… riding a racebike with a 130km/h first gear down cobblestone Paris streets on a wet, cold night. He was more comfortable on the motorway but had to stop for fuel. That created a second problem. The fuel he bought had an additive to improve economy, which caused one piston to nip up. Now he had to nurse the engine to keep it running. He arrived at the team’s hotel in Le Mans half frozen and found the crew in the logical place, the bar. In the days before mobile phones he might have been left stranded on the motorway. The next morning Ralph Hannan replaced one piston. The paddock rebuild surprised rival teams with their large transporters and sealed engines. Ralph had already decided his paddock hero was the fabricator who made the exhaust system for the six-cylinder Benelli Sei.

Hannan Equipe was joined at circuit by motor-vehicle wheeler-dealer Dennehy, in a Ferrari Berlinetta flat-12. The locals began taking them more seriously. While others didn’t. Ross said fuel supplier Total neglected to put the team on its customer list. When they needed petrol to wash parts they disconnected the Ferrari’s fuel line.

The Superbike proved genuinely quick when compared with the factory Hondas and Yamaha TZ750s. French-Moroccan-Australian Vic Soussan qualified fastest on a TZ750. (See sidebar.)

“It was only a roadbike; no special shocks,” Ralph said. “Until Ross found the Koni guy. But the engine was awesome. So fast. The Godier-Genoud guys came over after one practice and said Croz had passed their bike up the straight. But it wobbled there and under Dunlop Bridge. There was no chicane then. I don’t know how they rode it.”

Ralph’s initial misgivings fell away and he later rated the Le Mans experience above wrenching for Molloy when he finished second in the 1970 world 500cc championship.

“The big thing was to work with those guys and the opportunity Ross gave them,” he said. “Tony refined it all and Croz could just ride. Croz would say the bike was great, loved it. Then Tony would ride it and say it was terrible, a pile of shit… He’d fix it and Croz would find it really good. They were world-class riders even back then.

“We stuffed up because we didn’t have the budget and we’d never done a 24-hour race. If we’d had the bike ready from the start, we could have won it.”

On the Saturday morning the team headed to Mulsanne Straight to jet the bike. Back in the paddock, a last-minute check under the tappet cover revealed a valve collet had pulled through. Another engine rebuild and the Kawasaki rolled on to grid space 13 with 10 minutes to the pit gate closing. The riders nursed the engine for the first two hours so it didn’t seize again and then cut loose, gaining places.

An excited Hatton told the crew after one stint: “I just passed Phil Read!” He was on a factory Honda. To top it off, he saw Crosby motor past Takazumi Katayama’s TZ750 up the pit straight, on the back wheel! According to yearbook Motocourse, David Dixon told them to stop showboating.

The crowd had already twigged that the Superbike was special. A then 20-year-old Parisienne Philippe Roche rode to the event on a Yamaha 125 and recalls: “In this field of streamlined prototypes, the Hannan Kawasaki Superbike with its road looks, high handlebars and wild noise was really a sensation that stood out from the rest and was a crowd favourite.”

Hatton was the senior rider but he was learning from Crosby.

“I was trying to race everybody, until Croz told me to just follow them around the rest of the circuit and nail them with acceleration between the hairpin and the kink in the start/finish straight. So he was smart for his age. He also taught me a trick to racing at night, which was to stop trying to turn into the corner and just pick a pivot point. That takes a lot of confidence in yourself, but Croz picked it up the first time.

“I could see where he had been on the track by big black lines on the road with a hook at the end from spinning the rear tyre.”

Meantime, Crosby found a diversion during Hatton’s riding stints… Seeking the attentions of another rider’s girlfriend in his caravan while he was on track. It was becoming quite an adventure, according to the Kiwi. He was always good at value adding to a story.

“Two riders for 24 hours? Multiple seizures with the poor fuel, foreign country, pit shenanigans, working out of a small Repco steel tool box with Hatto, Ralph and Rosko… What could possibly have gone wrong?” Crosby said. “A great experience that allowed me to pick up some good contacts for the UK. As a first big trip away, it was one of the best events. Jambon sandwiches, ‘Bo-Jolly’ red wine and the drifting smoke and smell of barbecues across the track at midnight… Priceless and a big yarn to add to my repertoire of stories… Other details withheld pending censorship.”

In the early hours of Sunday morning the team had more dramas. The cause? It depends on who you ask. Ask Ross Hannan today and he wants to shoulder the blame. “We could change the battery every hour, but an hour wasn’t long enough to recharge one,” Ross said. “We were running out of lights. Croz could deal with that but Tony struggled.”

Moreover, the strain of hour-on, hour-off stints on a poor-steering, weaving bike wore down the riders. Eleven hours into the race and they were not relishing racing until 4pm Sunday.

However, in 1978 Crosby pointed to Hatton and tyres: “I had ridden Ross’s bike long enough to know it needed a Michelin on the front and a Dunlop on the back to handle. Tony decided we needed a Michelin on the back. I’m the test rider, so I get to try it!”

It was fine for a dozen laps, before the rear tyre let go and Crosby went into the catch fencing, which he thought was the best feature of the circuit.

“I wasn’t going that hard,” he said.

“Croz had a crash when the bike had virtually no lights,” Ralph said. “It wiped off the Krober ignition and damaged the brakes.” Crosby could not push the bike, so he grabbed a beer from a spectator and walked to the pits. He was told to retrieve the bike; they were still racing. He put tools in his leathers, did a quick repair and pushed back to the pits.

Ralph Hannan again: “Team Kawasaki manager Neville Doyle had given us KR750 front brakes. I couldn’t bleed that set-up because it had a five-eighths inch master cylinder and I only had tools for a three-quarter. It took two hours. So much stuff went wrong.”

The team elected to press on to finish. Hatton began to feel the cold of the early morning. He ‘borrowed’ a Champion spark-plug jacket from the previously mentioned rival. Hatton thinks what happened next was a result of dew on the tarmac. He crashed the bike and wiped off the ignition. Again. They had covered 317 laps and were out of the race. The Champion jacket was left in tatters. Ross Hannan swears a French journalist told him the torn jacket left French coins on the ground and Hatton went to retrieve them.

“Tres bizarre,” said the journo.

French Honda pair Jean-Claude Chemarin and Christian Leon won the race, covering 763 laps or 3255km in 24 hours at an average speed of 134.6km/h. Team Hannan had planned to move on the following week to the Thruxton 500-mile race, the sixth and final round of the Coupe d’Endurance. But with the Superbike damaged, everyone except Crosby went home. He secured a pick-up ride on a Norton Commando.

The Z1000-based Superbike was scrapped. Ralph was never happy with the frame. Doyle gave the team a Kawasaki Z1-R, which Ralph built up as a fabulously successful Superbike.

In 2009, Ross Hannan told me he was offended by the reception their effort garnered, with headlines appearing such as ‘Les Kangaroo’ and ‘Aussie Bizarre’.

“We had something different and made a genuine effort on the budget we had. I always had a good opinion of Australian motorcycle racers, especially over the Poms!” he said.

Hatton had finally made his European debut. He had been keen to try his luck in England in 1972 with his Yamaha R5 350 ‘Q-ship’ but personal reasons kept him in Australia.

“The bike was strong but we were totally unprepared,” Hatton said this year. “It woke us up on how not to do it. We had horsepower and rear grip, but the chassis geometry was all wrong. The bike was always going to wear us out. It was a handful and Croz was braver than me.

“We were in the right frame of mind, but 24-hour races are different. We were battled-hardened from doing two-, three-, four- and six-hour Production races here. I did enjoy a couple of one-hour ding-dongs with Phil Read. He’d pass me up the hill and I’d pass him somewhere else.

“We had lots of mechanical problems, detonation, the ignition being on the side of the engine, even the battery shorting on the petrol tank. But I was glad I went.”

Undaunted after the 1977 experience, Ross Hannan sought new challenges.

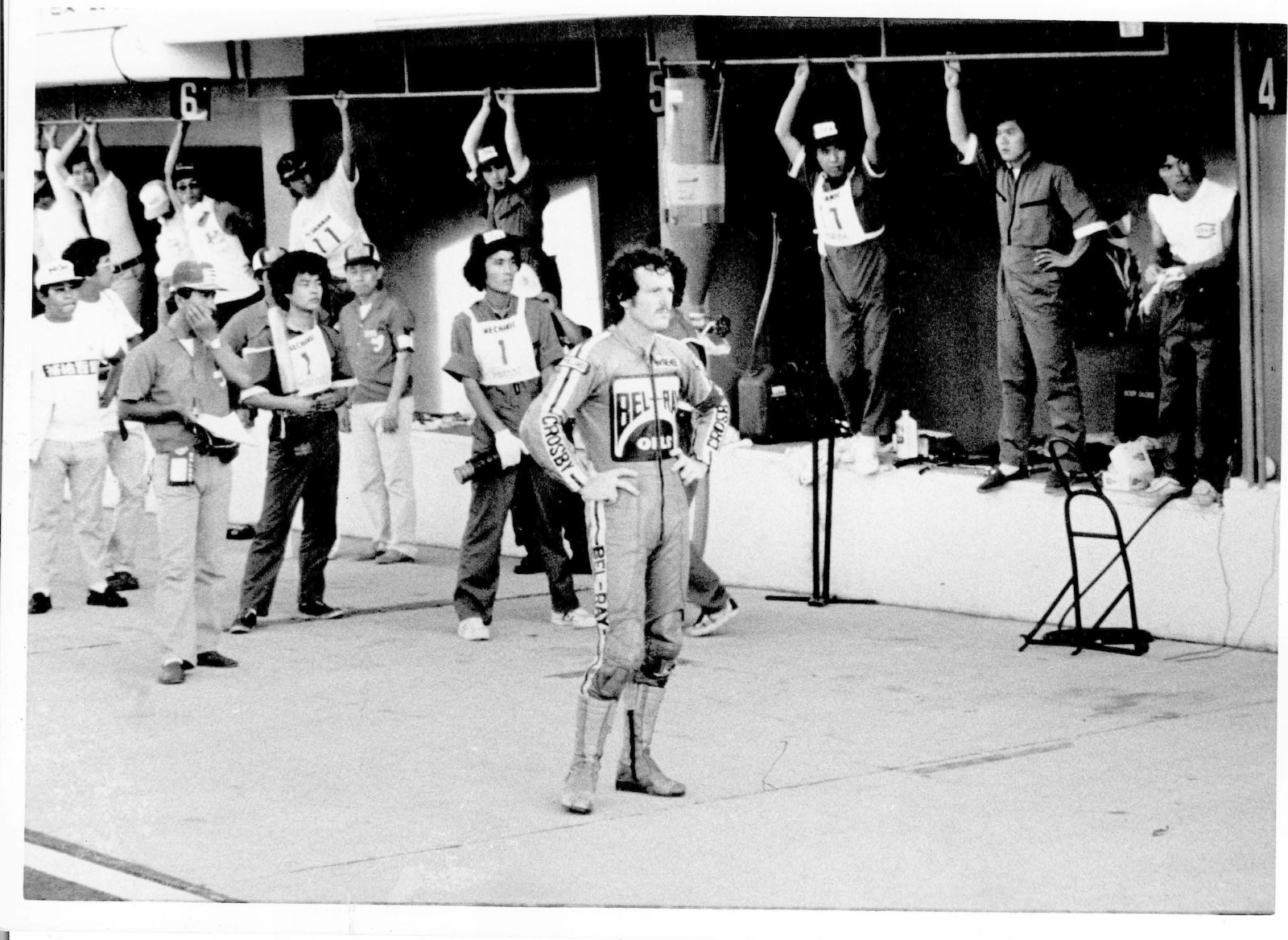

He flew home via Japan to visit Yoshimura and Pop’s son-in-law Mamoru Moriwaki, who was based near Suzuka. The local motorcycle club wanted to run an endurance race. Hannan was all in for that.

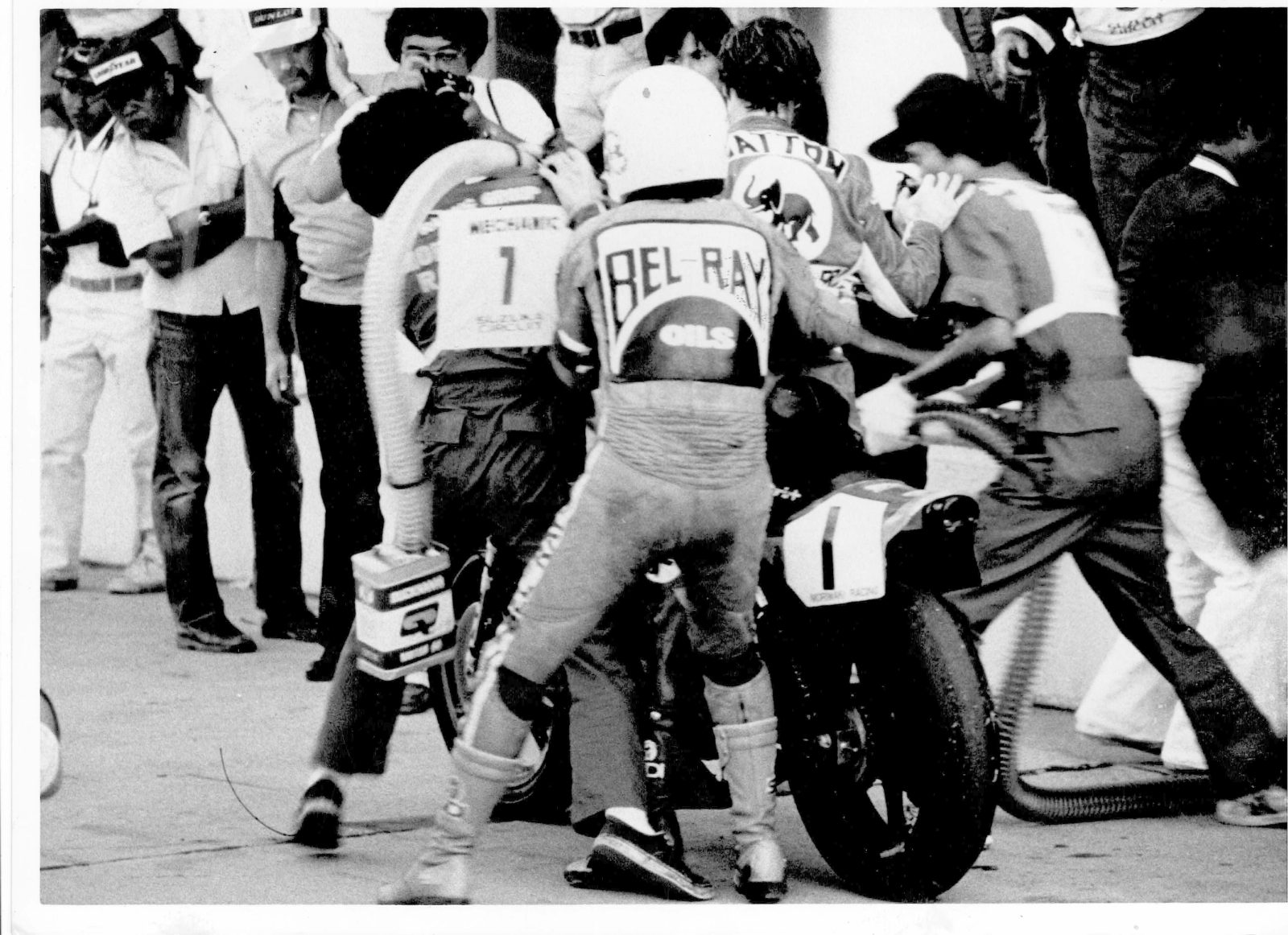

Moriwaki built a Superbike for the inaugural Eight Hours in 1978. Crosby/Hatton were in with a winning chance until the bike ran out of fuel. Hatton pushed it back to the pits in blazing humidity and they finished third.

In 1978 the Bol d’Or was moved to Circuit Paul Ricard, with its huge back straight and higher average speed. Ross commissioned a prototype chassis and Moriwaki supplied the engine. They ran the lights from a Honda Civic car alternator, mounted under the carburettors. The engine broke 32 laps into the race. Chemarin and Leon won again, covering 603 laps of the 5.8km circuit or 3508km at 146.6km/h.

Crosby rode in the Brands Hatch endurance championship round the following week, finishing seventh with Bernie Toleman on a UK Kawasaki.

Hatton went on to win the 1979 Suzuka Eight Hours with compatriot Michael Cole for the Honda Racing Service Center, the forerunner of HRC. They had struggled throughout practice to make the Honda 1000 rideable, talking late into the nights in their shared hotel room on the improvements they might make. Learning from 1978, they did not use the hotel air conditioning, avoided alcohol, walked the circuit every morning and drank “tonnes of water”. After the race, Cole produced one of the great quotes of Australian motorcycle racing: “All those nights laying awake thinking we were wankers and now this!”

Hatton and Cole were due to represent Honda RSC in the 1979 Bol d’Or, but Cole crashed and broke his leg. Hatton called in good mate Ken Blake and they made a strong quest for victory until their gearbox malfunctioned.

Crosby won the 1980 Suzuka classic for the Yoshimura-Suzuki team with Wes Cooley. By the end of 1982, he had matched his then team-owner Giacomo Agostini’s feat of winning at the TT, the Daytona 200 and Imola 200. He had also finished second in the world 500cc championship.

WORDS: DON COX PHOTOGRAPHY: DC & AMCN ARCHIVES