Rimini, Italy, 1950s. Every Sunday an Italian boy walks from his house to the barber for his weekly trim. The barber always talks to the boy about his great passion: Gilera. His shop is full of race photos of the famous brand located in the northern Italian city of Arcore, not far from the Monza circuit.

The barber shop is a meeting point for bike enthusiasts. Customers linger as every race, every parts update and every rider are analysed. The boy listens in amazement. The barber’s favourite rider is Geoff Duke because thanks to Duke, he says, the Gilera Quattros received a new chassis. And because of that, they won world title after world title… The boy never forgot those stories.

In 1960 at the age of 17 he got his first job at a Piaggio dealer in Pontedera. He enjoyed working with metal and repairing scooters and motorcycles, and was good at it all. A few years later he met two people, Valerio Bianchi and Giuseppe Morri and a friendship developed. In 1966 the three friends founded a new company called Bimota, which came from a combination of the first two letters of the last name of the three friends, Bianchi, Morri and the young boy who used to visit the barber every Sunday, Massimo Tamburini.

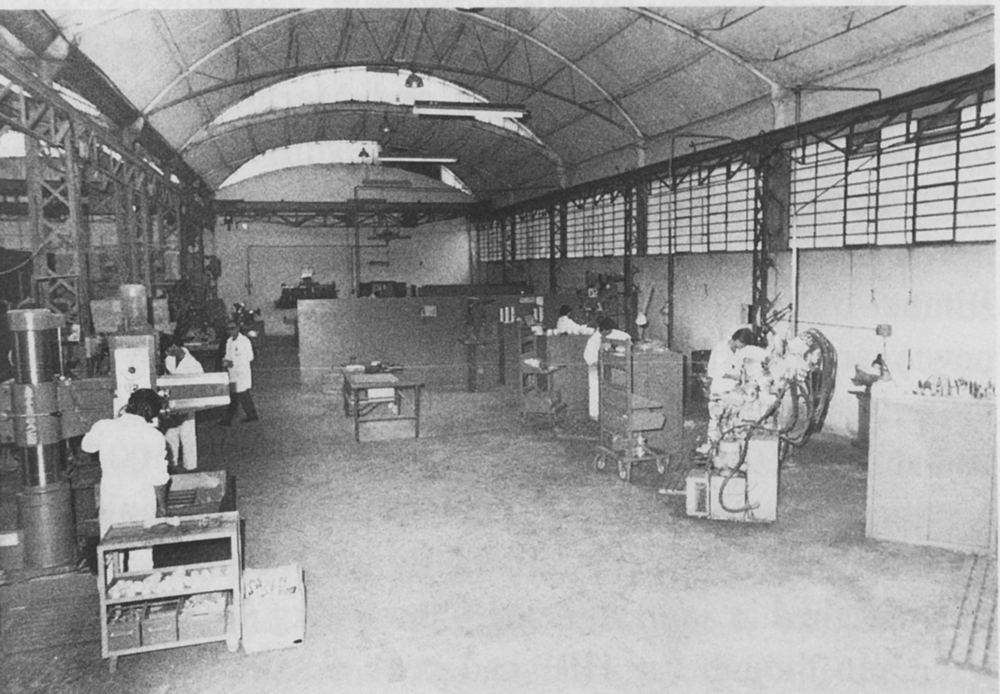

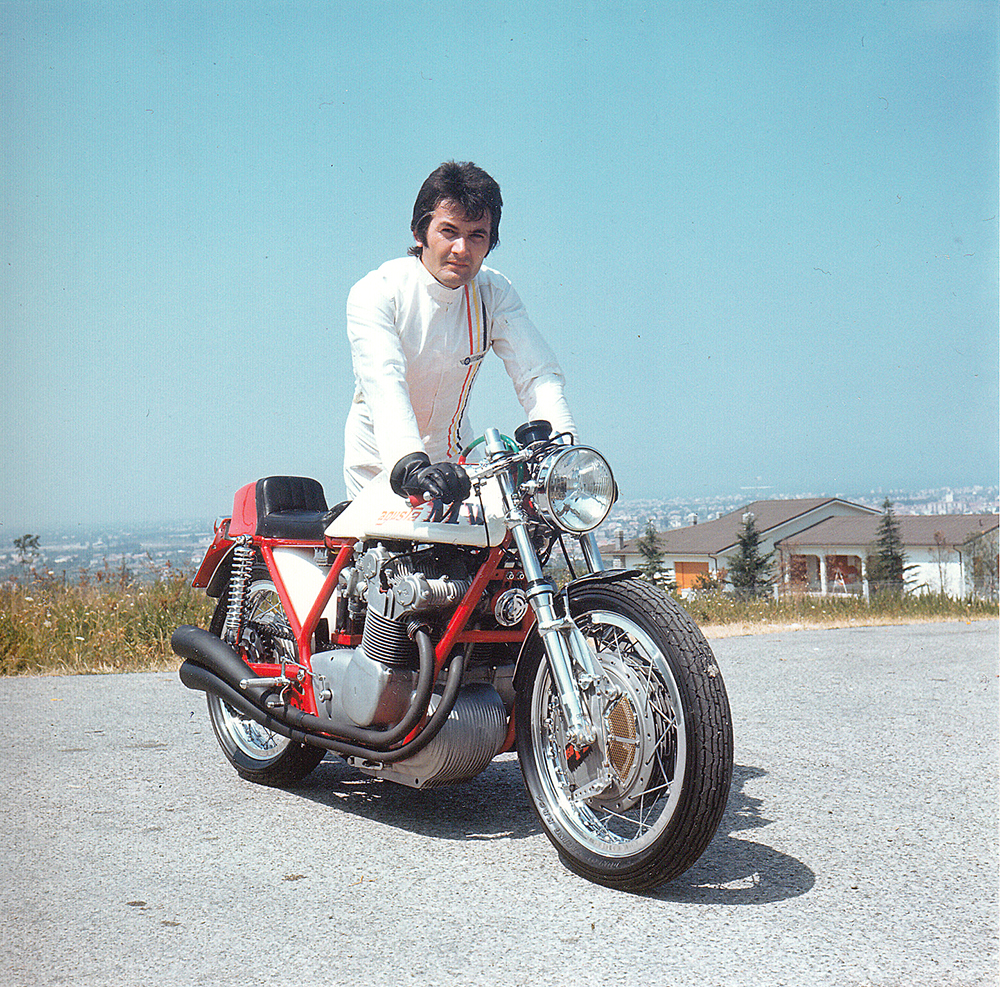

While it is often believed that in the early days Bimota only built motorcycle components and frames, in fact the company manufactured air conditioners and heating systems in 1966. This changed in 1971 when Massimo bought a secondhand MV Agusta 600. The MV’s four-cylinder engine resembled the Gilera GP racers he had admired so much in the past.

Tamburini rebuilt the engine increasing the capacity to 750cc, designed and made a completely new frame, replaced the shaft with a chain final drive and made new clip-ons, triple clamps and rearsets. Everywhere he went, the motorcycle was admired, but he was also pestered by the Carabinieri. Fed up with this unwanted attention, he sold the MV special and bought a Honda CB750.

A serious race crash on it at Misano left only the engine usable, which led Tamburini to develop a new frame and swingarm. The bike was ready in April 1973. It was the HB1, the Honda-Bimota 1. Almost immediately there was demand for both the motorcycle and the frame and requests came flooding in for frames specifically manufactured for grand prix racing.

By then Bianchi had left Bimota, leaving Tamburini and Morri faced with a difficult choice: the stability offered by the air conditioners and heating systems, or an uncertain future focusing on motorcycles. They chose the latter, and Bimota Meccanica was born.

In order to generate capital, Bimota started designing special parts with which riders could upgrade their Japanese streetbikes. Parts based on the HB1 project became available for various Japanese four-cylinder roadbikes. Components such as magnesium wheels, swingarms in square steel tubing, fibreglass fairings, seats, fenders and fuel tanks, rearsets and lighter clutch housings. These parts were available for Honda’s four-stroke CBs from 400cc upwards and Suzuki’s two-stroke GTs above 380cc. Meanwhile, the list of special parts for Kawasaki’s Z900 and Z1000 was certainly the most extensive.

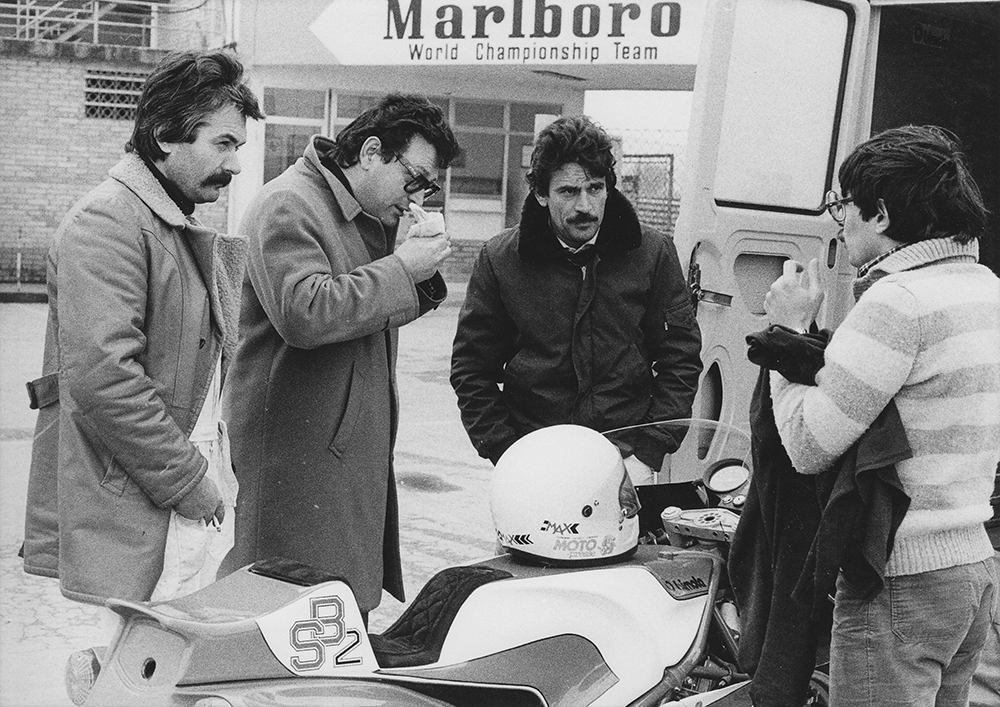

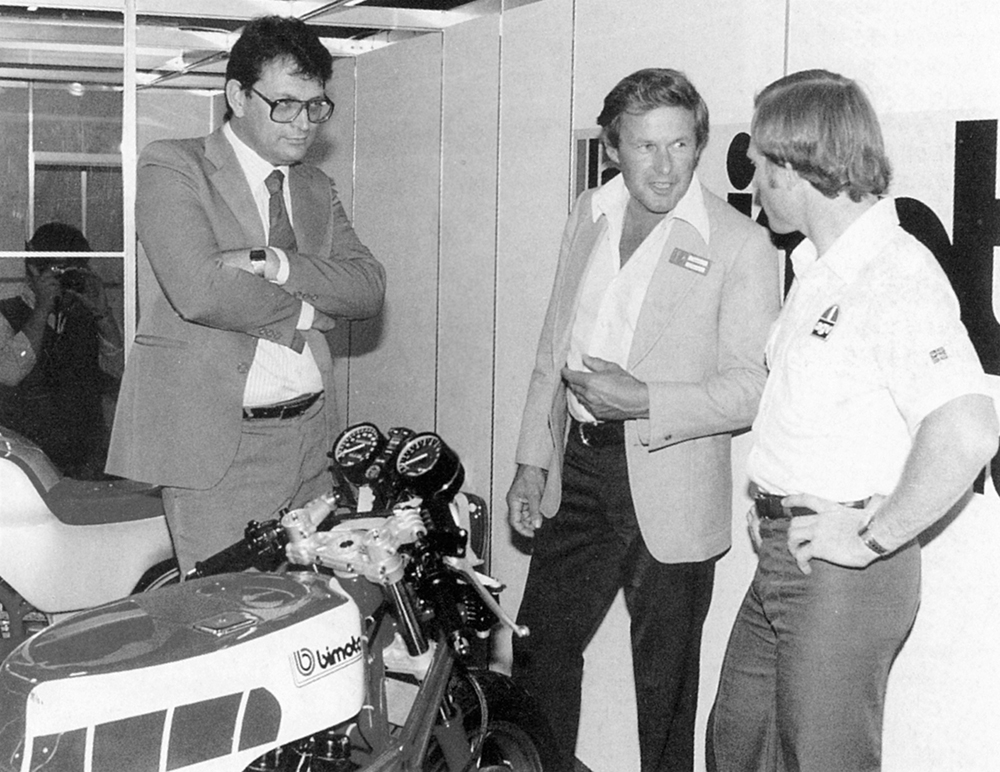

Available as individual parts or in kit form, Morri and Tamburini attended the 1975 EICMA motorcycle show in Milan to spruik their wares. There were three bikes on their stand: the 500cc HDB1 and 250cc YB1 GP racers as well as a Kawasaki Z900 rigged with the Bimota special parts kit. The response to the Kawasaki was so positive that it became fairly clear that there was a healthy demand for complete bikes made by the small brand from Rimini. So at the Bologna Motor Show one year later, Bimota introduced its first ever roadbike – the SB2, or the Suzuki Bimota 2.

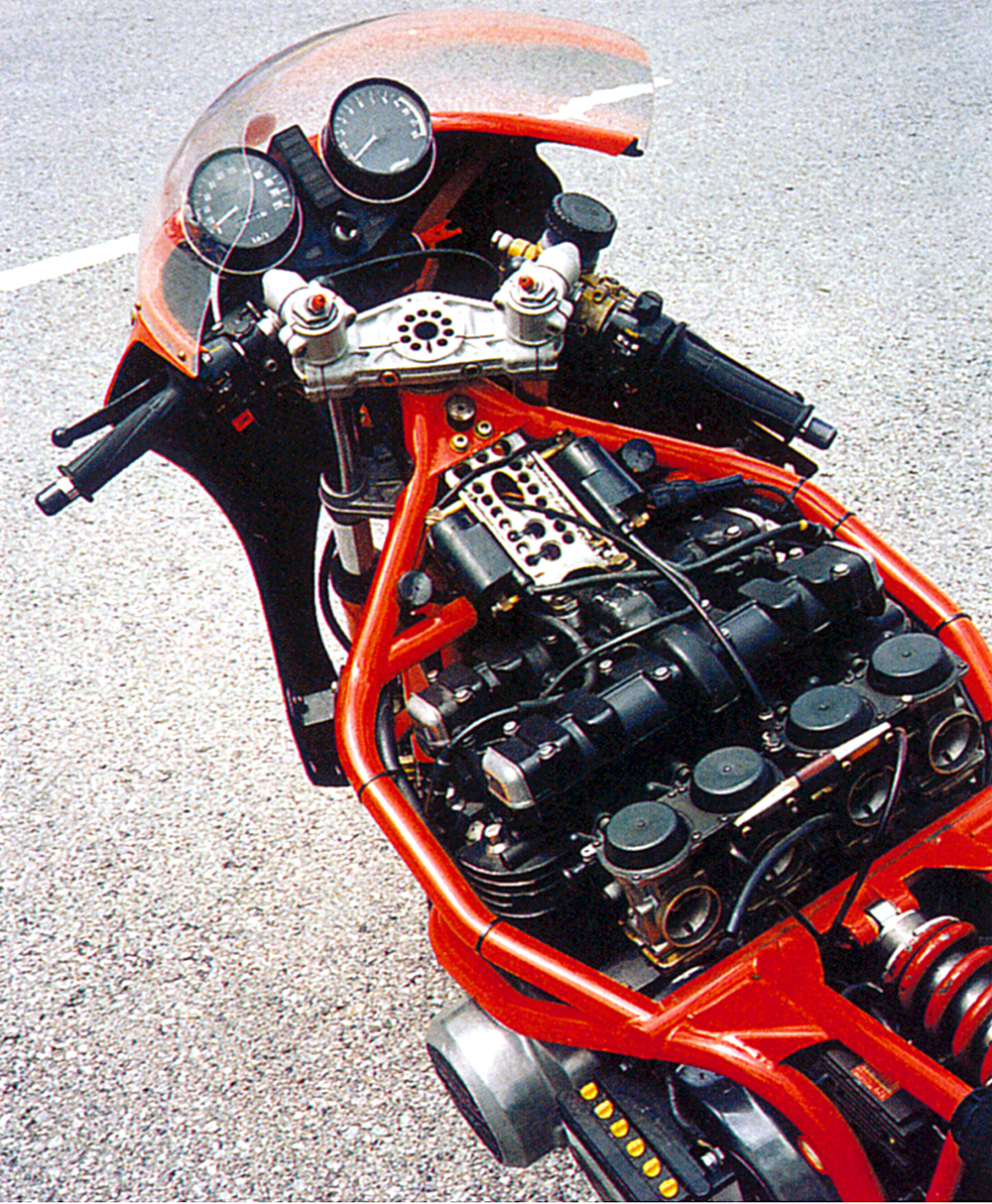

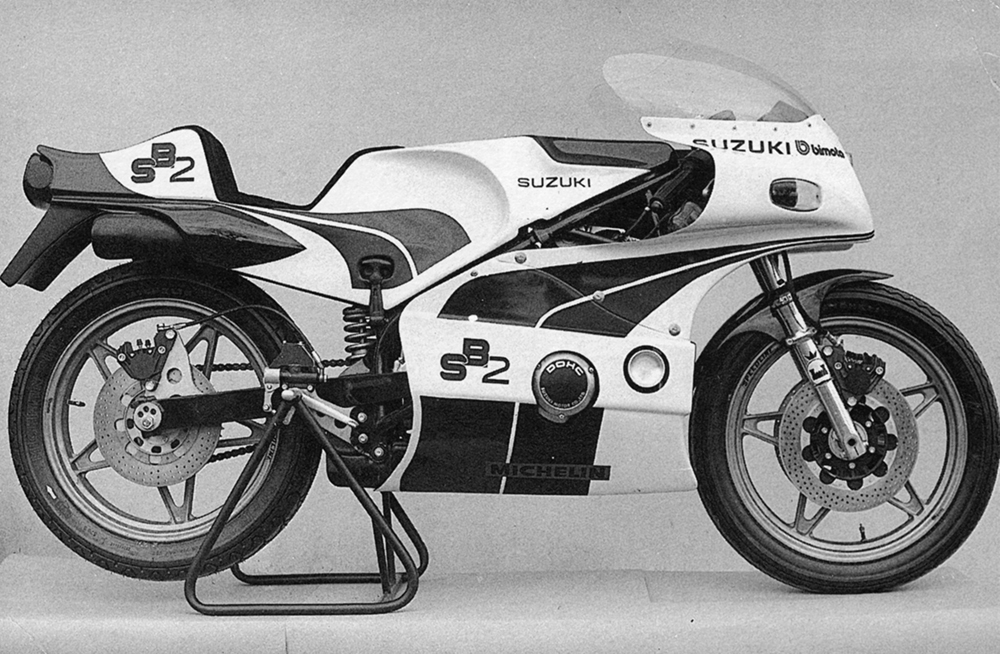

Unlike the 500cc SB1 two-stroke racer, the SB2 was Bimota’s first streetbike. And an amazing one at that. Designed by Tamburini, the prototype was far ahead of its time using a Suzuki GS750 engine. The SB2’s most striking feature was that the fuel tank was located under the engine, while the exhaust system ran backwards where the tank would normally be with two mufflers exiting underneath each side of the seat.

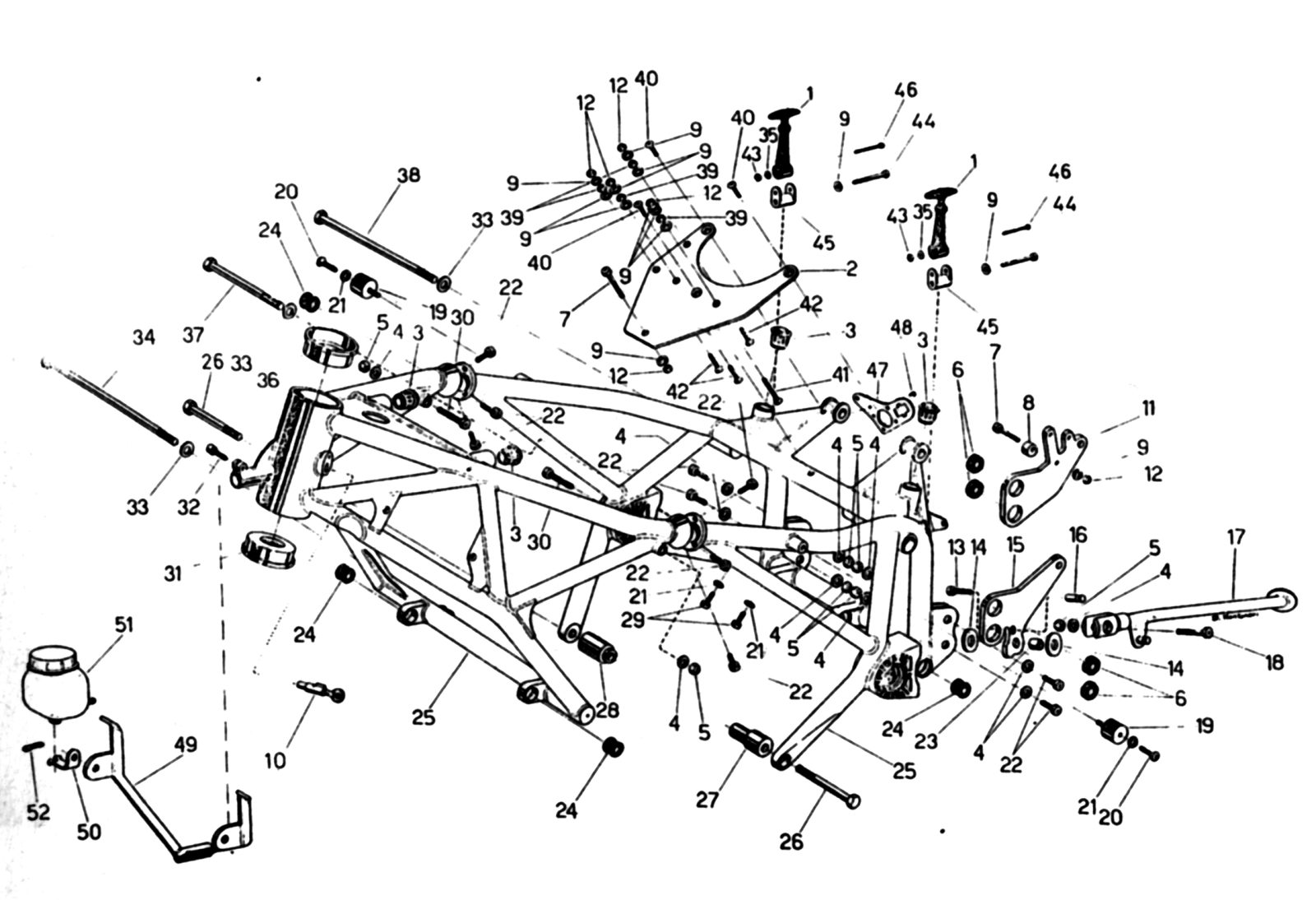

The air-cooled four-cylinder 750cc DOHC engine remained almost standard, delivering 56kW (75hp) at 8700rpm (a stock GS750 produced 72hp at 8200rpm). The engine was housed in a lightweight chrome-molybdenum tubular trellis frame that weighed 8.5kg. The extremely stiff and strong frame could be divided into two halves – useful for repairs or replacing quickly after a crash. The front and rear of the frame could be replaced quickly, too, and very easy to align thanks to the conical mounting points. His use of progressive rear suspension in the form of dual shock was a first for the industry.

The steering head was placed at an angle of 25 degrees, but the 35mm Ceriani front fork was not mounted at the same angle – another first – and the fork angle was actually adjustable by up to 29 degrees via eccentrically mounted triple clamps, meaning the trail could also be changed by up to 20mm shorter or longer. If you were planning a trip on winding roads, you could opt for short trail for the fastest steering response. However, if higher speeds and long sweeping corners were on the riding agenda, longer trail could be achieved for enhanced stability.

The tank and seat were mated together. The SB2 got star-shaped lightweight magnesium cast wheels made by Campagnolo. The brakes came from Brembo, where two-piston brake calipers operated twin 280mm front discs and a single 260mm disc at the rear. At 196kg (dry), the SB2 was 27kg lighter than the standard GS750 and could reach a top speed of 220km/h, 25km/h more than the standard bike – any wonder the SB2 was hailed “revolutionary” by the media at the time.

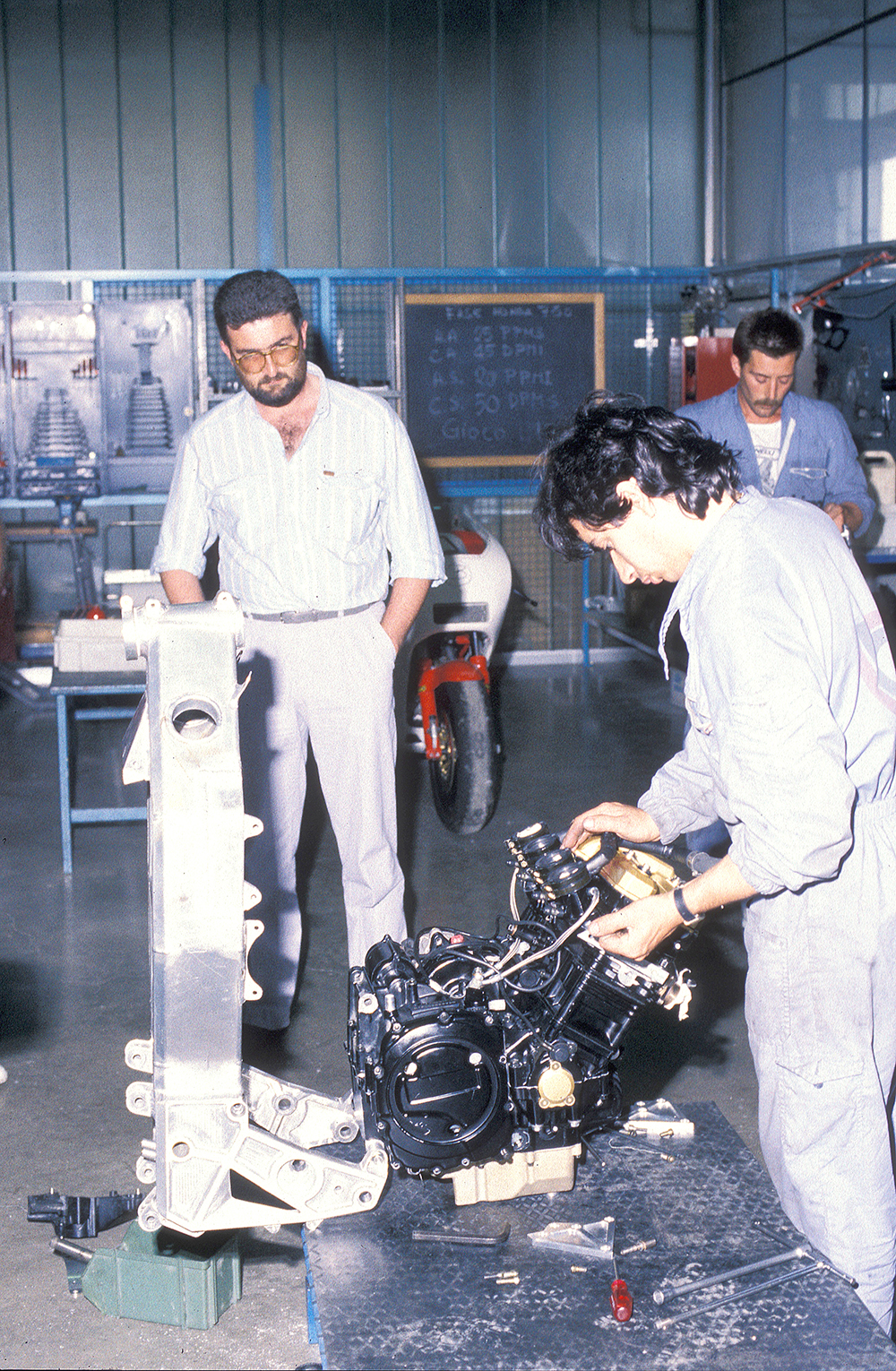

After the show in Bologna, Tamburini went to work to get the SB2 ready for production. A number of concessions were made due to the complexity and high production costs.

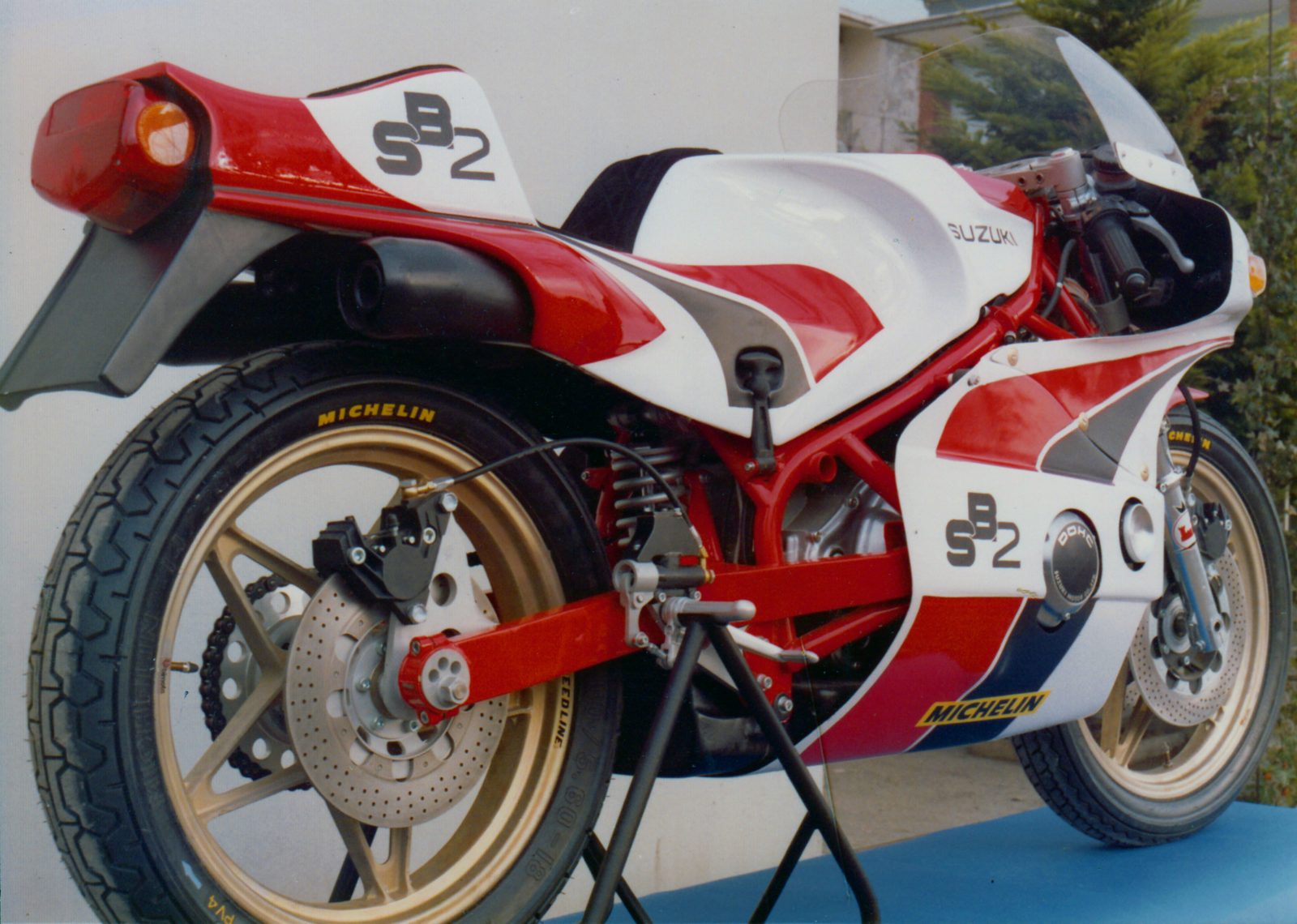

The unique placement of the tank and exhaust was abandoned and returned to their conventional positions. Rear indicators were mounted in the openings left by the prototype’s exhaust routing, while the double shock absorbers gave way to a single Corte & Cosso unit that was produced for Bimota under a special license from De Carbon. In 1977 the production version of the SB2 was introduced at the Milan show.

A huge task for a very small manufacturer like Bimota, but hardly a risk. Saiad, the Italian Suzuki importer, initially ordered 200 machines before reducing its order to just 50 units. A total of 140 bikes were eventually built, with Italy and the Netherlands taking 50 each, 30 to France, five to Germany and another five to various other countries around the world.

With 60 frames left over, Bimota put a second version of the SB2 into production – the SB2 80, which was introduced in 1979. It had much more conventional bodywork and was in production between 1979 and 1980; only 30 were made and the remaining 30 frames were destroyed.

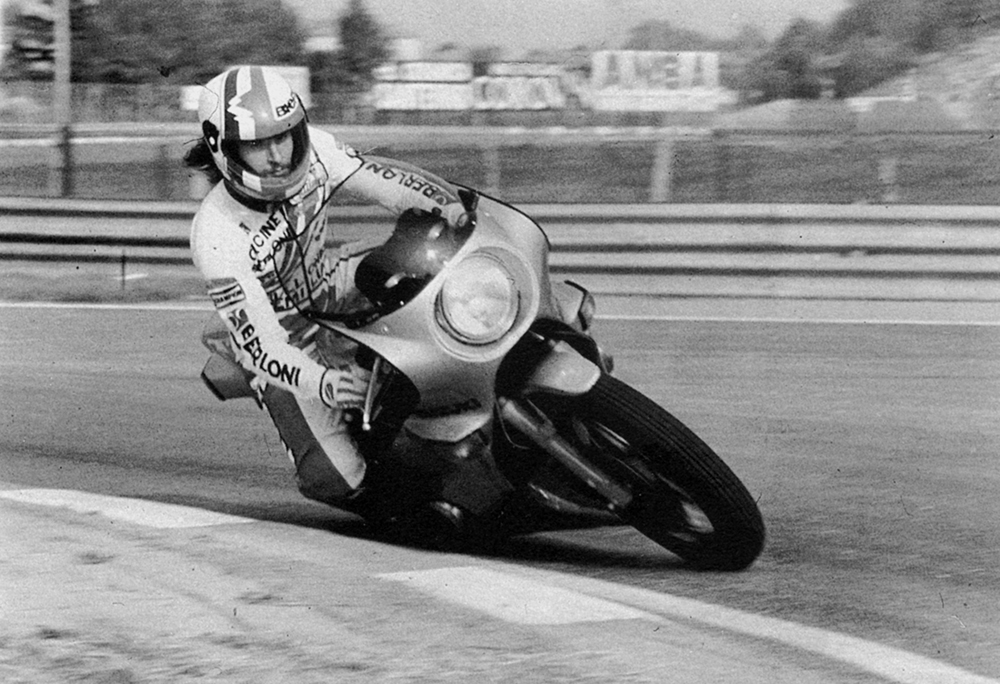

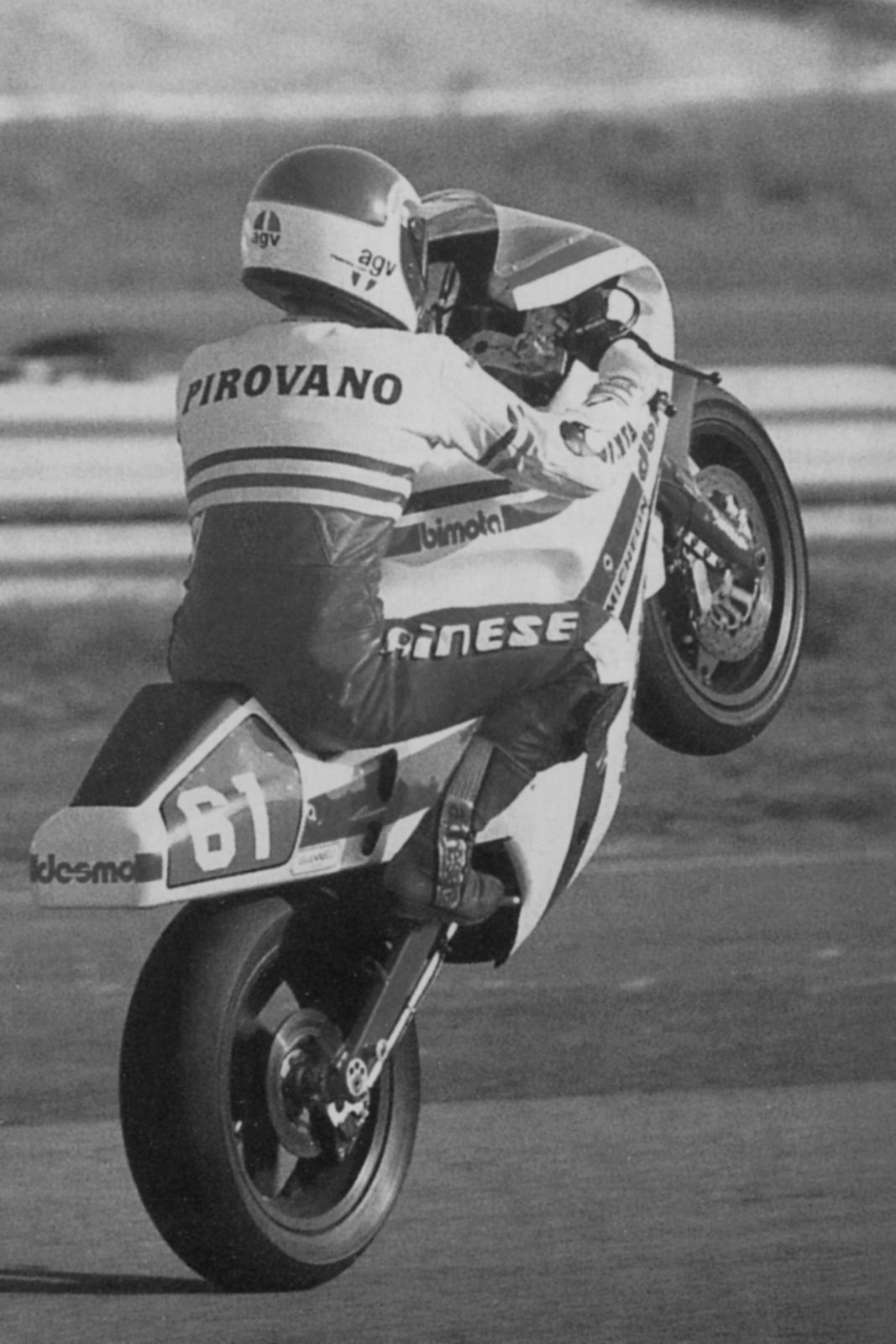

That doesn’t take anything away from the innovative Bimota SB2, a machine that was very enthusiastically received by the motorcycle world back then. The SB2 also had successes in endurance and stock production racing with just a tuned engine and a larger fuel tank.

The SB2 was one of the first decent handling production motorcycles powered by a Japanese engine. While people were divided on its appearance, the press unanimously agreed it was “grand prix level” in terms of performance. Bimota was in a class of its own in terms of frame, components and concept.

The SB2 was succeeded by the more conventional 1000cc SB3 (1979-1982), while the last Suzuki Bimota was the SB8, powered by the TL1000 V-twin. It was produced from 1998 to 2005.

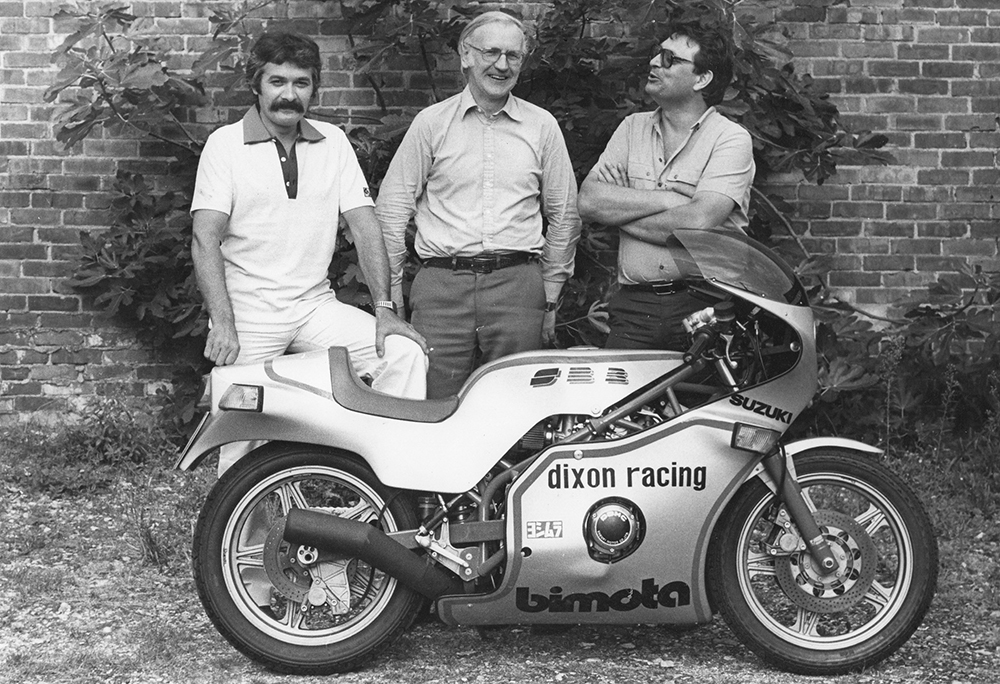

In 1977, Bimota used EICMA to unveil one of the most successful models in its history: the KB1. Available in a 900cc, 1000cc or in kit form, the 1000 version was powered by the 1015cc four-cylinder engine of the Z1000 delivering (63kW) 84hp at 7950rpm. The 900 version used the 903cc engine of the Z900. The KB1 had a dry weight of 193kg and could reach a (measured) top speed of 233.8km/h. A standard Z1000 weighed 256kg (dry) and could achieve 210km/h.

A total of 827 KB1s were built between 1978 and 1982, 16 as complete motorcycles and the rest in kit form. Exhaust manufacturer and engine tuner Luigi Termignoni created a special version of the KB1 with a bored out 1200cc engine and a trick exhaust. That resulted in a spectacular – and measured – top speed of 287.5km/h.

Kawasaki then became the first manufacturer to supply new engines directly to Bimota, starting with a GPz550 mill for the 1981 KB2 which was bored out to 600cc for the racing version.

The 1000cc successor of the KB1 was the KB3, powered by Kawasaki’s 77kW (103hp) Z1000J engine. The KB3 was very similar to the HB2 and the SB4. Bimota had started to build the motorcycles modularly, so that multiple engines could be mounted in the same rolling chassis via engine specific mounting plates. The KB3 would be the last Bimota with a Kawasaki engine until the 2019 EICMA show where the KB4 broke cover.

In 1983, Bimota unveiled the DB1, which was powered by Ducati’s 750cc belt-driven engine. Tamburini had left the factory, and it was now managed by Giuseppe Morri and Tamburini’s successor Federico Martini who was previously employed by Ducati. Bimota actually developed the DB1 as an assignment for Ducati. However, the owners of Ducati, the Castiglioni brothers – aka Cagiva – did not like the first prototype. At that point they already had footed 50 percent of the development costs, so Bimota offered Ducati a full return if they could retain all rights to the design and future production. Ducati agreed and the DB1 went into production in 1985.

As a counter move, Cagiva hired Tamburini. The Castiglioni brothers asked him to design a new, more all-round Ducati model with styling characteristics based on the DB1 prototype. The result was the Ducati Paso. Tamburini went on to design Ducati’s 916 and Cagiva’s new four-cylinder project which was badged as the MV Agusta F4.

The DB1 was the start of a successful range of Ducati-engined Bimotas and even raced by Davide Tardozzi of Ducati MotoGP fame in the Superbike World Championship.

Most of the DBs (DB2-DB6) were fitted with the two-valve Desmodue engines of 904cc, 992cc and 1078cc capacity. The liquid-cooled, four-valve 1098cc and 1198cc Testastretta engines were used for the DB7-DB11, the latter manufactured in 2013. At that juncture Ducati terminated engine deliveries to Bimota.

The uncompromising Mantra DB3 900, made in two versions from 1995-1998, was designed by Frenchman Sacha Lakic. The name was taken from the Sanskrit language, meaning ‘tool of thought’ and was Bimota’s attempt to expand the line-up with a nakedbike.

The iconic YB4 (1988-1989) was the first Bimota to use an aluminium twin-spar frame. Powered by an FZ750 engine, it was the first road Bimota to use a Yamaha engine; the YB1, YB2 and YB3 were GP racers. As a factory bike, a prototype 750cc YB4 won the 1987 Formula TT World Cup with Virginio Ferrari. Over the years the YBs would grow to 1000cc thanks to Yamaha’s FZR1000 engine, with and without the EXUP system. The YB9 series featured Yamaha’s FZR600 engines and the series ended with the YB11 in 1998. That engine came from the 1000cc Thunderace, the bike weighed 209kg (dry) and had a top speed of 261.5km/h.

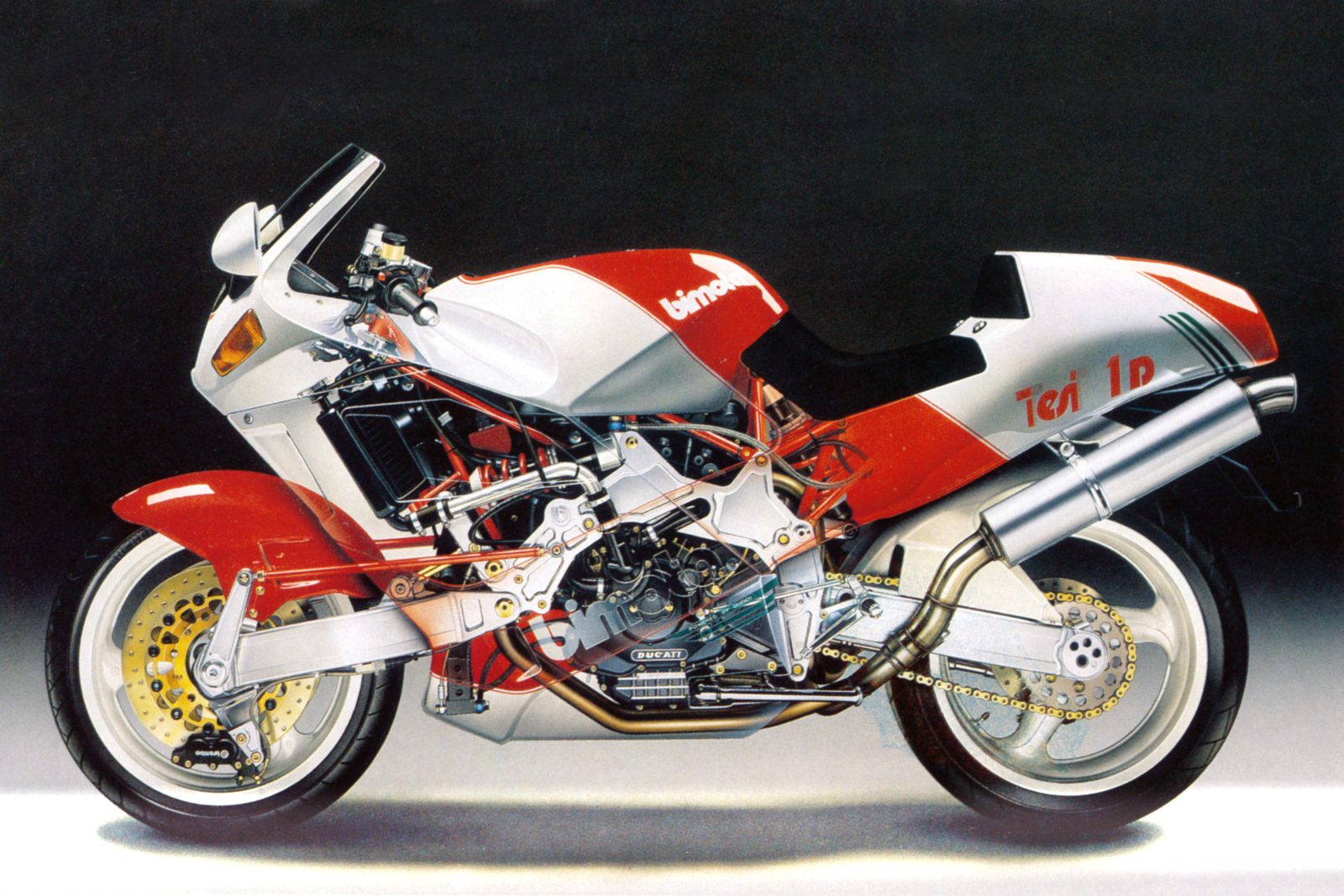

In 1990, Bimota released the Tesi 1D. Designed by Pierluigi Marconi, the Tesi 1D was the first in a series of Bimota Tesi models that used a hub-centre steering system. Though not continuous in production, most Tesis like the 2D and 3D were powered by Ducati engines.

Throughout the 1990s Bimota produced the BMW Bimota series, starting with the BB1 and BB2 Supermono with a F650/Rotax engine and the S 1000 R-powered BB3 of 2012-2015. The HB4 entered production in 2010, using a Honda CBR600RR engine. It was the successor of the 1983-1985 HB3 which had a CB1100 engine, and the 1982-1983 HB2 which was powered by the CB900 Bol d’Or engine.

In 2020, with Bimota acquired by Kawasaki after decades of unrest and financial instability, Kawasaki’s supercharged 998cc H2 engine was used for the new Tesi H2, which is still available today. The other 2023 Bimota models, the KB4, KB4RC (naked) and the BX450 enduro, are all Kawasaki powered.

Bimota has faced many challenges over its 50 years, but the company’s commitment to innovation and high-performance motorcycles has allowed it to remain a player in the motorcycle industry. The acquisition by Kawasaki has provided the company with the stability and resources it needs. And long may it continue.

Words Ivar de Gier + Photography Archives A. Herl & Bimota