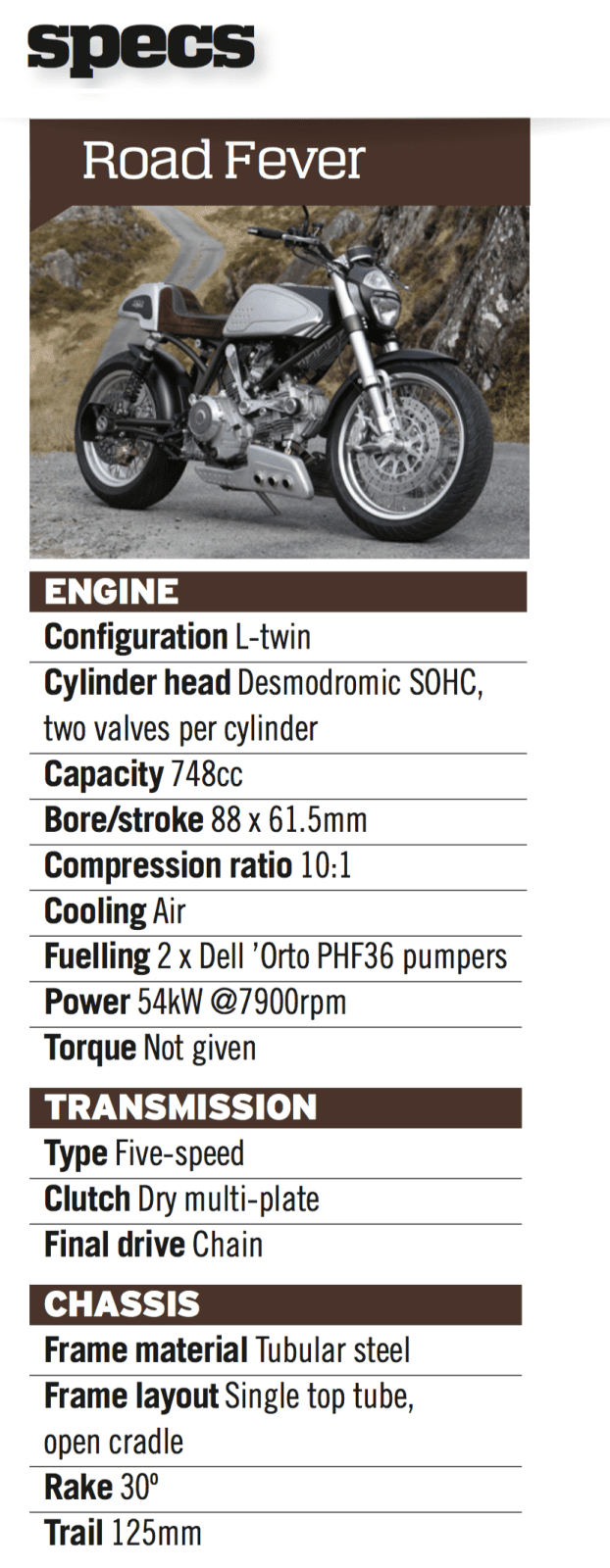

Mick O’Shea cranks the bike he calls Road Fever into a tight left-hander, grabs a handful of his 73 horses and drives them hard as he accelerates towards the top of the Healy Pass that separates County Kerry from County Cork. We’d left Kenmare only half an hour earlier and the roads were beginning to dry after the morning rain. This is Ireland, so wet roads come with the territory, but Mick was optimistic and left the wet-weather gear at home. “It’s going to brighten up this afternoon,” he promised before we set off.

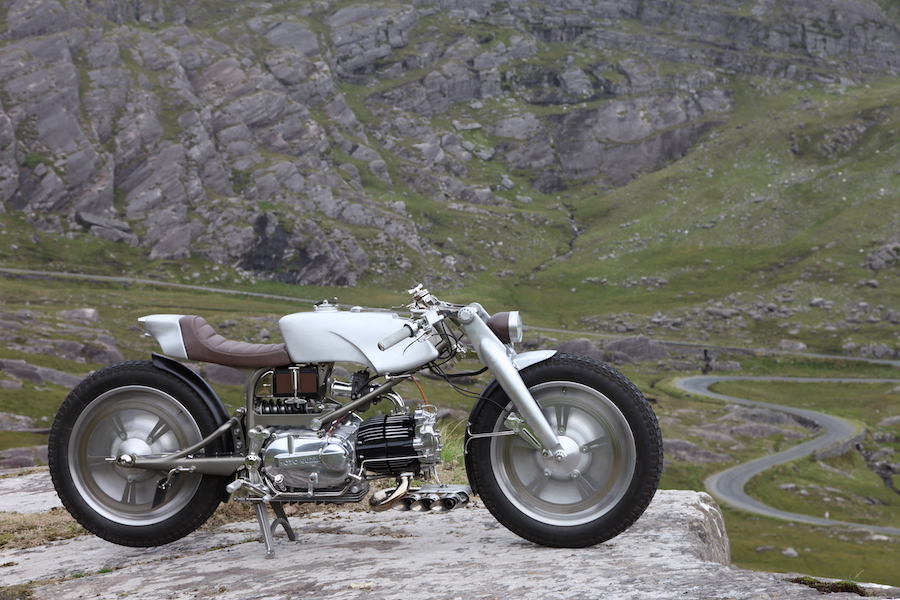

The Healy climbs from Lauragh, over the Caha Mountains and down to Adrigole on the south coast of the Beara Peninsula. It’s only 14km long but the R574 is one of Ireland’s finest roads, a mix of hairpin bends and bumpy straights with spectacular views across the rugged landscape. But we’ve only just started. Mick built Road Fever with his friend Don Cronin because he wanted a custom bike that he could ride hard. Note his choice of words: custom bike. “It’s not a café racer,” he says. “Everyone does those.”

And he has a medal to back up that claim. This is the bike that won the 2016 Street Performance class of the AMD World Championship of <i>Custom Bike<i> Building. Entries flooded into Germany’s Intermot exhibition centre from 23 different countries. And the beauty of the judging is that bikes are voted for by the competitors themselves.

The Street Performance class is designed to showcase customs where the primary intention is to improve the street-use performance of a motorcycle. Of course, the bike has to showcase the builder’s performance engineering, tuning and chassis development skills in a package that looks as good as it rides. As Mick O’Shea’s mate Don Cronin says, Road Fever was probably the only performance bike entered that had been ridden hard on the road.

We hang a left at Adrigole and follow the coast to the fishing port of Castletown-Bearhaven, with views across the Atlantic to Bere Island. Then it’s through Cahermore and north towards Allihies. Mick’s bike seems to almost float over the bumps. His suspension is a huge advance on the Hagon shocks and Eddie Dow two-way damping in the fork of my old-school Gold Star cafe racer.

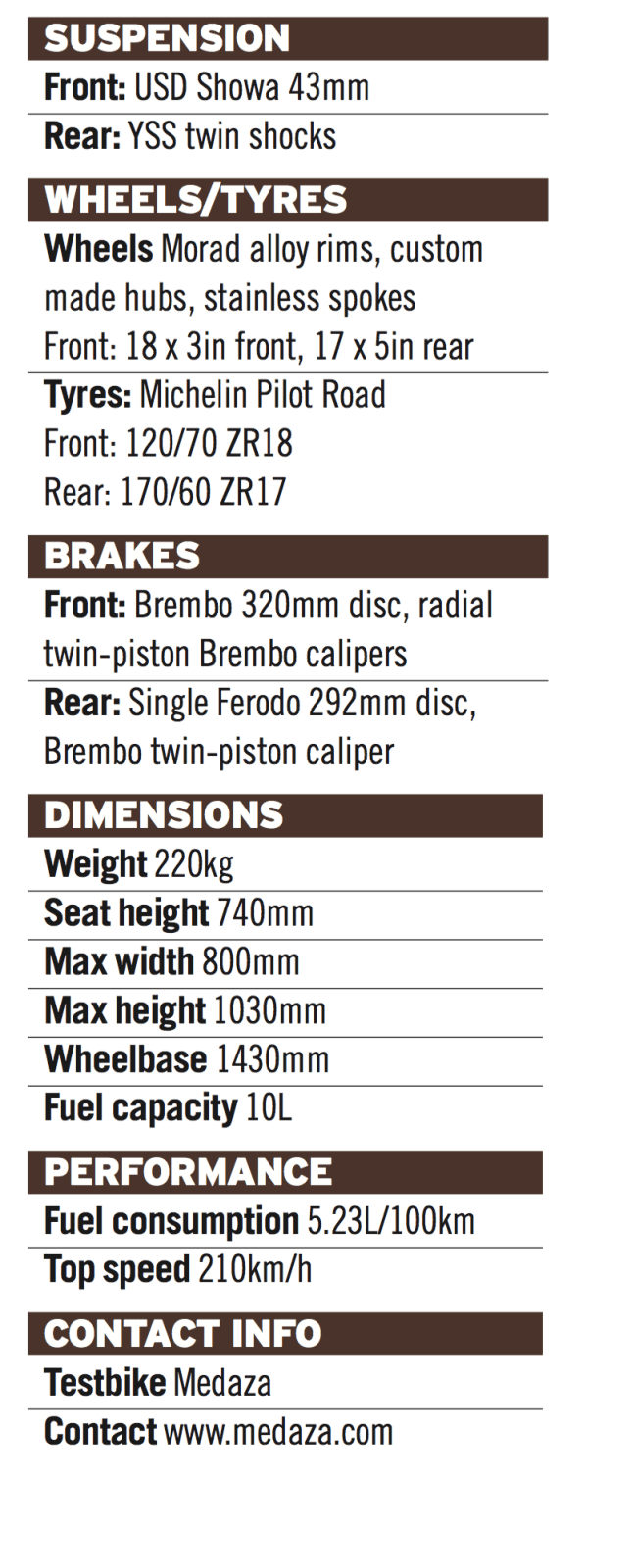

We stop at O’Neil’s bar for a coffee and take the opportunity for a closer look. It might be hard to believe, but Road Fever started life as a 1987 Ducati Paso. Introduced the previous year, the Paso was the first Ducati to be built under Cagiva ownership. The bike was designed by Massimo Tamburini, who took the air-cooled engine from Ducati’s hot 750 F1 Sport, a road racer with lights. The rear head of the desmodromic SOHC L-Twin was turned through 180º so that the inlet manifolds faced each other between the cylinders. Now Tamburini could use a single twin-choke Weber carburettor, like the ones used on Italian sports cars, instead of the F1 Sport’s two 36mm Dell ’Orto pumpers. That would help the Paso pass American emission tests. The two-valve heads were basically the same as the F1 Sport’s but with larger valves and slightly retarded valve timing to give more power at lower revs. The engine cases were stronger, and the 14-plate dry clutch was hydraulically operated. But even with a 10:1 compression ratio, maximum output was slightly down on the F1’s 56kW.

While the F1 featured a gorgeous round-tube trellis frame based on the Verlicchi TT2 racer and a Marzocchi cantilever monoshock, the Paso used a double-cradle frame constructed from box-section steel and an Öhlins Soft Damp shock with rising-rate technology. The box-section alloy swingarm featured eccentric adjusters at the rear. It might have been ugly, but it didn’t matter because the frame was hidden behind slab-sided bodywork that looked as if it was borrowed from a Bimota DB1 (Ducati Bimota One). No surprises there – Tamburini was the ‘ta’ in Bimota.

The Paso ran on 16-inch wheels front and rear, which were supposed to make the bike nimbler in tight twisties. But although the sports-tourer Paso was good for around 210km/h and could cover the quarter-mile in less than 13 seconds with a terminal speed of 160km/h, it wasn’t a great success. That Weber caused a big flat spot in the mid-range, and low-speed running was a pain in the arse. And not everyone liked Tamburini’s styling.

Mick’s Paso spent 10 years in the back of a shipping container before he dragged it out. “I like the Pantah engine,” he says as he pours another coffee. “I was really impressed by the 350cc version I used in a bike I built a few years ago. It only had 32bhp [23.9kW] so I thrashed it everywhere and it never let me down. But I wanted a bit more power, and a bigger petrol tank – the one on my 350 only held 5.7 litres and that was a pain on motorways.”

Mick’s idea was to put what was basically a 750 F1 engine into his own steel tube frame … and that’s where Don Cronin comes in.

“We set the engine up in Don’s homemade frame jig and put the headstock and the axles for the 18 x 3.00in front wheel and 17 x 5.00in rear into position, using the wheelbase and overall frame geometry of a 600 Pantah,” explains Mick.

Don is a sculptor and used his artist’s sense of form and his rider’s sense of function to build the frame. Like all good designs, it is strong and simple – the engine hangs from only two mounting points. There is a single 48mm diameter high-carbon steel top tube, with one pair of 26mm tubes coming down to pick up the mounting point between the cylinders with a second pair of hand-bent tubes extending to the rear engine mount. Another pair of tubes runs back from midway down each rear frame tube to support the seat and the top mounts of the Taiwanese YSS twin shocks. Because Mick’s inside leg measurement is only slightly more than a leprechaun’s, the seat height is lower than on a Pantah.

The braced swingarm is another work of art. Each side is constructed from two tubes – one 34mm and the other 26mm – with beautifully CNC-machined housings for the eccentric wheel adjusters that were salvaged from the Paso. Rotating the eccentrics moves the wheel backwards or forwards about 15mm to tension the drive chain while keeping the wheels in line – modern ‘O’ ring chains don’t need much adjustment. “Don didn’t like the look of the eccentrics at first,” says Mick, “but they are my homage to the 1980s, and they’ve grown on him.”

The USD front fork, radial calipers and Brembo discs were donated by a 2008 Monster 696, along with the lower fork yoke. “I machined the top yoke from a 6kg block of 60mm thick alloy,” adds Mick. After failing to find a front hub to carry the twin discs, he decided to machine his own. And while he was at it he machined the rear hub as well so that he could use the Paso’s bolt-on cush drive. To cut down on cleaning and polishing – these Irish roads can get muddy as well as wet – Mick had the hubs and Morad alloy rims clear anodised by Hagon, who also spoked the wheels. The modified headlamp came from a 1200 Monster, while the combined speedometer, rev counter and fuel gauge is a Danmoto unit. For the custom look, Mick decided to fit a pair of Magura handlebars, with neat Magura 195 master cylinders and brake and clutch levers. The footrests, brake pedal and gear lever came from a Panigale.

On top of showing his talents in tube bending and frame fabrication, Don crafted the seat unit and the alloy petrol tank. “He had an old CB450 tank lying around, and that provided the inspiration for the shape,” says Mick. “Don also came up with the idea of polishing the ‘side panels’ so that they looked like the chrome panels on the Honda, and adding the dimples where the knee grips would be.”

Ger Colon at Spectrum FX in Cork was the man responsible for paintwork. Although it is all one piece, the top panel of the tank is painted matte black to make it look smaller than it is, with the rest in silver metal flake. “That’s another homage,” interjects Mick, “this time to the Silver Shotgun Ducati desmo singles.”

The engine internals are stock Paso, but the Weber was junked in favour of a pair of Dell ’Orto PHF36 pumper carbs. Attention to detail is everywhere – check out the half-covers and machined pulley covers for the belt drives to the valve gear, the alloy oil cooler that sits between the front frame tubes, and the panels on the leather and suede seat. The seat hump, which hides the battery, incorporates the Medaza Cycles logo – this isn’t the first bike that Mick and Don have built. But to prove that you don’t need to make everything from scratch, the steel mudguards came from a 1990s Triumph Thunderbird (though Mick did make the bracketry) and the crankcase breather pipe is a Volvo component.

The original stainless steel exhaust pipes were polished up. “That saved a bit of work,” concedes Mick. “But Don thought that the silencer I was going to use looked a bit … boring. So he made the two alloy boxes that fit under the engine, with three ports on each side and dimples to match the knee grips on the tank. They face forward, and are angled in, so there’s no fear of grounding them out.” Boring they ain’t.

Mick was right about the weather. As we drain our mugs the clouds break up and the sun shines through. Just outside Allihies there’s a narrow track with grass growing up the middle that leads to an abandoned copper mine, so we make the climb to check out the views. Even with 10:1 pistons, Road Fever is every bit as tractable as my Goldie. I’m impressed.

Back on the coast road we cruise along the north side of the peninsular through Cahirkeen, hang a left to Eyeries and pick up the R571 back to Lauragh. We are both hungry, but there’s a great bar a couple of miles away at Kilmakilloge Harbour and you can’t beat a bowl of their fresh mussels with a glass of Guinness. As I sup through the creamy head and take a gulp of the black stuff I realise there’s a question I’ve forgotten to ask: why Road Fever?

“When I was a teenager, my mother used to say that I got ‘road fever’ as the weekend approached because I was looking forward to riding to rallies, bike shows or to see the road races,” explains Mick. He still hasn’t grown up.

This time the engine is a 350cc Pantah pinched from a Cagiva Alazzurra. Wheels are from a Harley-Davidson V-Rod, while the fork is off an Aprilia RSV Mille. Don also made the frame and tank for Mick’s bike. Mick has ridden it on a road trip to America and on the banking at Montlhéry in France. The build took four months to complete.

TEST AND PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP TOOTH