Australian motorcycling has something very special in its midst. It’s fueled by a mixture of determination and devotedness and unfortunately, too many of us won’t appreciate the significance of what Ken & Barry Horner create until it has stopped.

That’s not because the things happening there right now aren’t remarkable. But because the two brilliant minds in charge aren’t the kind of blokes who beat their own chests, preferring instead to let their impeccably engineered machinery do the talking on racetracks. And therein lies the problem. Because the very remarkable things they’re doing doesn’t currently fit in any strictly regulated racing category. Not in this country anyway.

Those two brilliant minds are Ken and Barry Horner, the brothers responsible for the Irving Vincent solo and sidecar race machinery that have enjoyed enormous success here and around the world. Amazingly, Irving Vincent is just one of a couple of side hustles for the Horners, whose main gig is producing sparkless air starter motors for the mining and fuel exploration industries – not that their trophy cabinet would let you think they’re both not full steam and full time on the brand. They also produce cylinder heads and specialist race parts for the Garry Rogers Motorsport Supercars squad, they’re the official Australian distributor for performance suspension brand K-Tech and, and were heavily involved in supporting Wayne Maxwell and Craig McMartin’s Boost Mobile Ducati squad in the 2022 Australian Superbike Championship. But walking through the vast and spotless KH Equipment factory in Melbourne’s south-eastern suburb of Hallam, it’s pretty clear these guys tend to excel at everything they turn their hands to.

The beginning

Ken and Barry grew up blasting around paddocks about 20 kays from where we’re standing, on “what we bought for about five dollars,” says Ken, now 70, the eldest of the two by just one year. “An AJS or a BSA or something, old pommie things. We’d pull the lights off and run up and down there with no helmets and no registration.”

I asked if their father was into bikes. “No,” they said in unison. “Engineering though,” offered Barry. “He had an engineering business. We were little kids in the workshop; it became part of us.”

The very first Irving Vincent made its public debut at the 2003 Island Classic at Phillip Island after a decision was made to completely remanufacture a modern version of the 50º V-twin Vincent engine. It was a decision made partly because they had access to the original drawings thanks to close a friendship with Vincent’s legendary Australian designer Phil Irving, but also because they love to challenge themselves.

“It wasn’t until 2000 that we thought we needed a project,” explains Barry. “We’d built a big yacht in the 1990s, a 46-footer that we built because we could, but you never use it. And that scene wasn’t us, so we got rid of that and went back to what we love in life – motorbikes.

“We knew Phil very well, in fact before he died [in 1992] we mentioned that someone should rebuild the engine. So we took a challenge – not necessarily to race, but maybe do a classic race

here or there.”

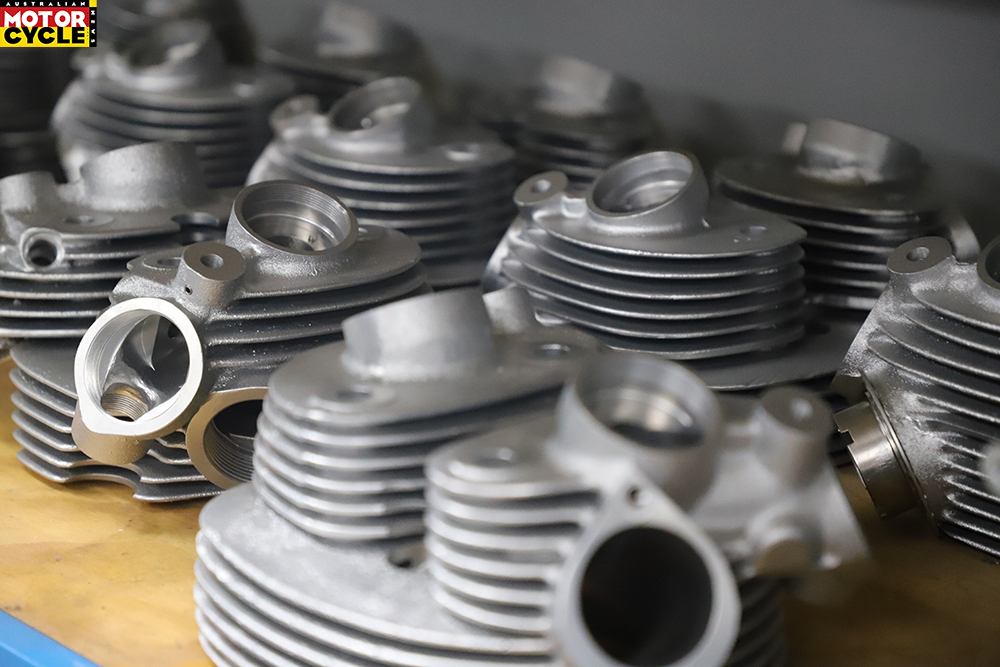

Twenty-odd years later, I look at the pair and ask how many there have been since. A quiet chuckle moves through the room before Barry finally says: “Well, we’ve got probably engine number 38 or 40, all in different stages.”

Phil Irving’s original 998cc Vincent engine produced 45hp in its day, and the Horners’ remanufactured versions are producing a reliable 155hp at worst.

“And now we’re up to just shy of 200hp on the latest version that we’ve done, which is a four-valve engine,” says Barry. “That’s the engine to go back to Goodwood – even though we’re not allowed to go back at this stage ‘cos we won by too much. The British Club doesn’t want us back, because we’re too quick. But we’re building the bike up anyway, as things might change.

“It’ll be faster again, though, so we might never be allowed back,” he adds with a laugh. And they’ve got to laugh, or else they’d probably cry. Both the Island Classic and Australasian Superbike Championship (ASC) were happy hunting grounds for their thoroughly modern reinterpretations of the original Vincent, with the highly competitive International Challenge and the ASC’s Pro Twins category providing racing platforms for the Horners, until both events’ eventual demise.

Their problem is, because of the engine design’s theoretical age, they need to run on methanol to help with cooling.

“We’re an air-cooled engine, we don’t want to take away the look of what an engine is,” says Barry. “We could easily put a water jacket around that and a radiator on it, but then it’s not any different from what a normal modern motorbike would be, so that’s not what we want to do.

“We would like to have some sort of dispensation of the fuel we run, like a methanol or E85, to keep the engine cooler to keep them alive, otherwise when you produce horsepower you produce heat. The cylinder heads overheat and get soft and the valves fall out.”

The successes

As well as at Goodwood, Irving Vincent has tasted plenty of success. Barry tells me the 1300cc solo has won every race it’s finished and holds lap records at Sydney Motorsport Park, Phillip Island and McNamara Park, taking as much as four seconds off the Period 4 lap record at the South Australian circuit.

“Two seconds under the lap record in the P5 class and the sidecar has the lap record, too,” he says.

Probably the most famous of wins came at Daytona’s Battle of the Twins event in 2008 when Craig McMartin rode the specially built two-valve 1600cc V-twin to victory.

“We wouldn’t have gone over as a long shot, we knew we were pretty well positioned,” Ken said, before smiling and adding, “And John Britten did it so we had to do it.”

And it’s that strong association with McMartin that led Ken and Barry to throw their support behind Maxwell’s final few ASBK campaigns, which he won on two of his last three attempts.

“The team came together from where we’ve been in the past, we know how we all think, we know how we all work,” explains Barry. “Other teams, if they don’t have a part or they can’t bolt something on, then it doesn’t happen. But Ken and myself, we just brainstorm and come up with solutions, if Wayne wants something moved by 5mm to improve his comfort or to get the bike right, then we can engineer ways to do that.”

Racing has been in the pair’s blood for 50 years. Ken had a Vincent sidecar that he built in 1972 and he raced that quite successfully, before turning his attentions to building the engineering business in the mid-1970s. Barry raced a Yamaha TZ750 with success, too, between ’77 and ’83, before getting involved with his brother in the business.

After showing its potential in British Superbike machinery, Ken and Barry took on the Australian distribution of K-Tech suspension in 2018, and with just 2.5 full-time staff assigned to the brand, have since grown to a 160-strong dealership network and quadrupled the turnover in four short Covid-affected years.

“We are their number two in the world after US,” says Ken.

As well as running the suspension on the Irving Vincents, and Maxwell’s and Josh Waters’ Ducati V4 Rs, KHE’s general sales manager Warren Niblock-Bell tells me that both Maxwell and Penrite Honda’s Troy Herfoss were testing K-Tech’s new TRDS shock for the duration of the 2021 ASBK season.

“And now probably a quarter of the Superbike guys on the grid have got it, they’re all jumping over,” Warren adds.

The heart

As Ken and Barry show me around the factory they’ve worked out of for the last three decades, their determination and drive to succeed at everything they do becomes really clear. But the thing that stayed with me after driving out of the large black gates surrounding the sprawling factory is the heart that’s so clearly evident in everything they do.

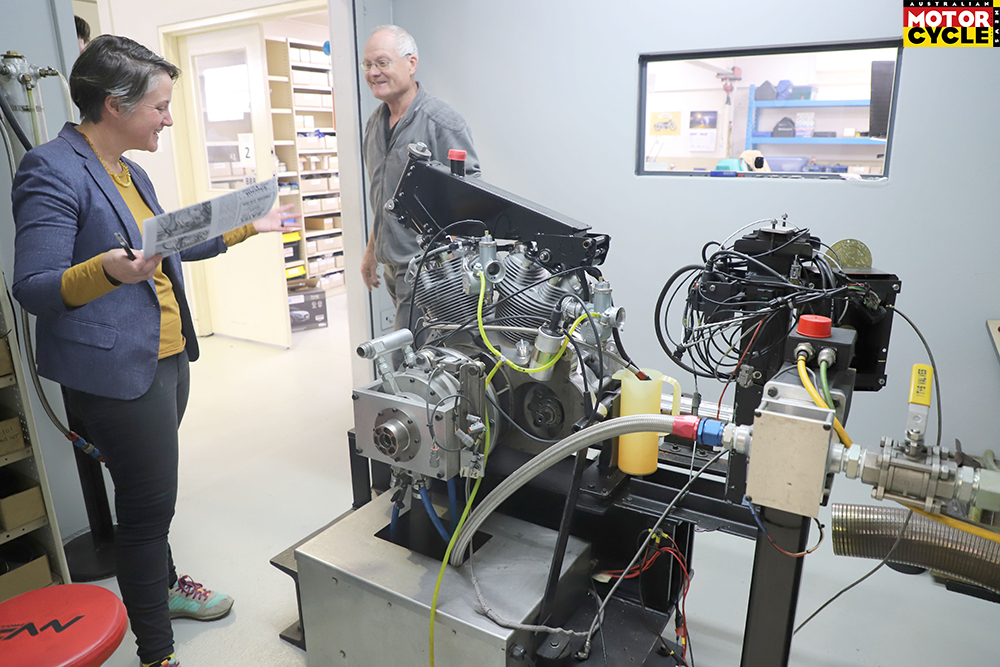

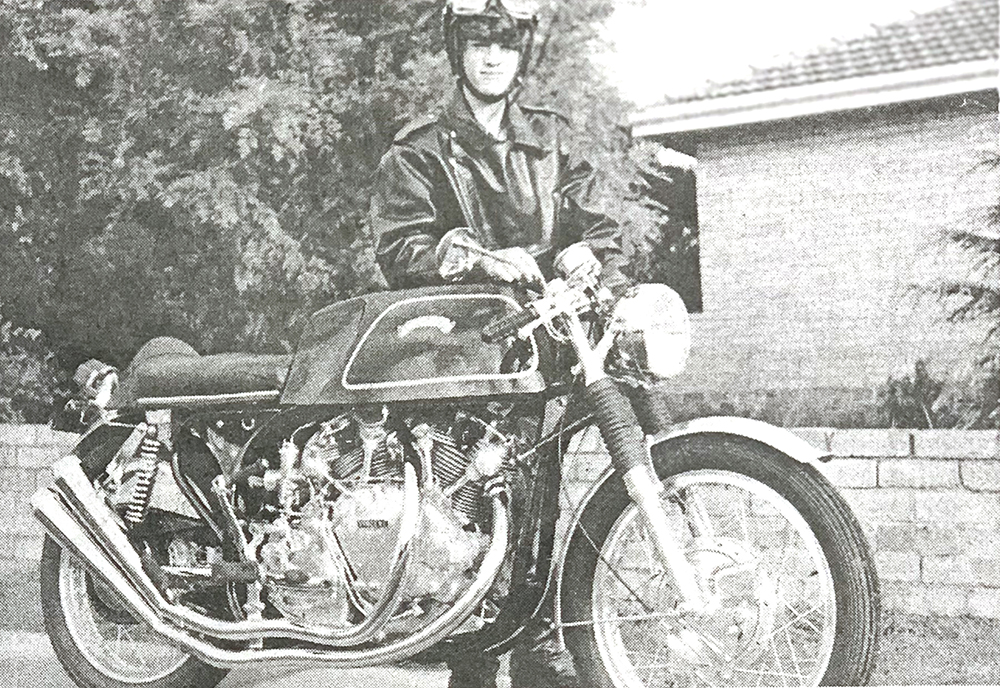

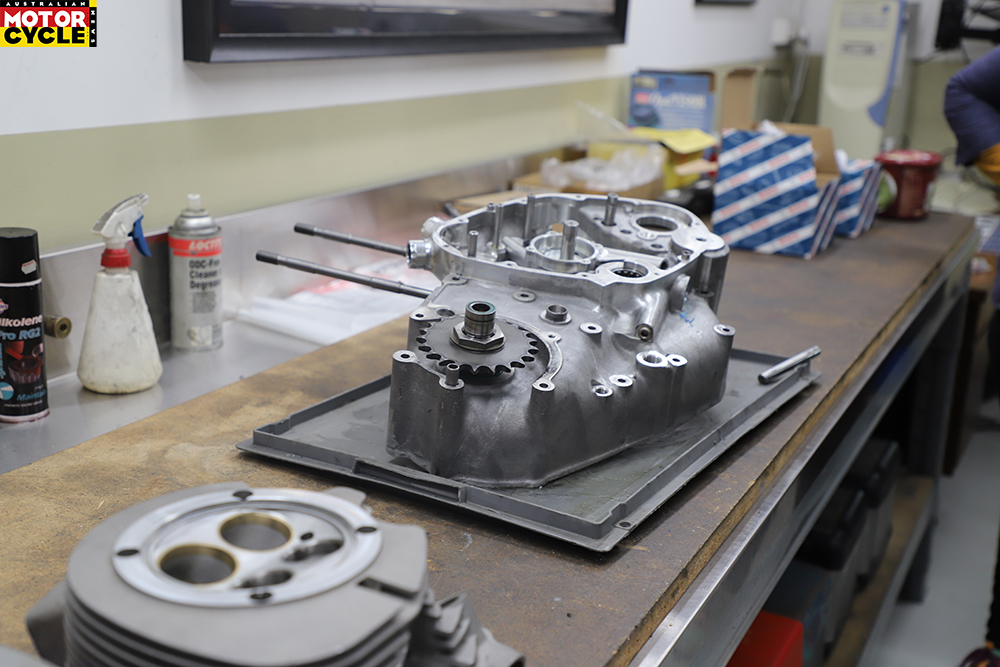

Whether it’s the scores of large indoor plants throughout the place because “they said they make people feel good,” or the pet cockatoo and galah who talk and dance as you walk past, one of which they “found injured on the side of the road,” or the pictures of family dotted throughout the place. It was evident when Ken appeared with a 52-year-old issue of AMCN featuring him as an 18-year-old with his 1950 Vincent Black Shadow.

“This is the bike here,” he says proudly, pointing to an engine and frame sitting on the bench. “It’s going through a rebuild… with some more modern type of comforts.”

And it’s also clear that their real passion lies firmly in the Irving Vincent machinery they’ve engineered with such enormous success. And all they want to do is race them, despite having fewer and fewer opportunities to do so these days.

Barry’s showing me the immaculate sidecars, starting first with the Period 5 outfit.

“I built that in 2005 and ran it through to 2016, but I had something in the back of my mind that I wanted to improve on, to do better, which was this one,” Barry says. “We raced it at the ASBK in 2017 or 2018 at Winton, they wanted extra numbers, so we asked if they wanted a Vincent there and they agreed. Up against the modern bikes, Beau [Beaton] goes and puts it on the front row of the grid and I think he ran a second and third and fourth, anyway we got third overall.

“We didn’t want the points, we told them we didn’t want the points, but in parc ferme they announce Beau as third and he said, ‘no, we’re not here’. Someone said ‘they’re running methanol anyway’, we said ‘it is what it is, it’s an historic bike, it’s got to run methanol’. We said ‘we’re not here for points, but sorry for going so good (laughs)’.

“The bloke comes down when we’re packing up and says ‘we’ve got to take the points off you’, I said, ‘for god’s sake, we’re not here for it, I don’t care – you’ve got to realise that people want to see this thing, it’s all about the show’.”

And that’s the heart I’m talking about. It’s Ken and Barry’s willingness to pour countless hours and untold amounts of money into building exquisite machinery, not to a spec good enough to win trophies, but to a spec good enough to appease the ridiculously high standards these blokes set themselves, and because in doing so they’re preserving important motorcycling history and keeping their word to an old friend.

“It’s frustrating that we have to fight for what we do so much,” says Barry. “We had a great turnout at Mt Gambier [Oz Historics], the spectators love us, everybody clicked. We make no money out of it, but when it’s a good meeting – even when you start one up, you know – and that’s why the challenge is there. Here’s an engine that was bought out in 1955 and the fact that we can kick arse with it is a real achievement, you know?

“The public’s reaction is so good, they came up to us and thanked us for being there. That’s what we do it for. It’s all love, satisfaction and the challenge.”

The future

Ken and Barry still have every engine and bike they’ve ever built, choosing not to sell them in a bid to retain control over where the engines end up and in what application.

“You couldn’t sell one,” says Barry. “That one won Daytona, and potentially we could have left that there and sold it for a squillion bucks. Someone wanted to buy it and we just said no, we didn’t even negotiate cos we had to bring it home.”

Warren interjects: “I’ve got the likes of Jesse James wanting to buy one. I literally get enquiries weekly of people wanting to buy the engines to put in Vincents overseas, especially in Europe.

“We’d like to head to Europe and build the brand, but what happens is they build one and then they fall in love with it and won’t sell it.”

Barry nods. “It’s alright if we sell one and they put it in the museum, but if they try and use it they wouldn’t know what to do with it and they’d destroy it,” he smiles. “You don’t want our product out there being bastardised. If people buy an engine and put it in a chopper, you know, that’s not us.”

I finally ask the question I’ve been wanting to ask all morning, and that’s if Irving Vincent has a future after Ken and Barry Horner. Here are two men who have spent 20 years preserving an important milestone in Australia’s motorcycling history, and all of a sudden they’re both looking down at their boots.

“Unfortunately, with all these things,” begins Ken, “it’s a bit like John Britten – you take him out of it, and you go, well, what’s left? And I’m not saying we’re John Britten. But when I can get some clear air, which should be sooner than later, we need to do something.

“A lot of these people have passionate businesses, you take them out and you’re taking the knowledge out. We are trying to catch up with a lot of these drawings and everything else we have, so they’re understandable. From day one, I did it fast, because we wanted to get there quick. But all the knowledge you’ve got in your head, it wasn’t documented or drawn exactly as it should have been.”

But eventually he gets to the point.

“I’ve already written the spec of what I would say would be a saleable item. But you won’t be able to put a numberplate on it – too many hoops, it’s just not worth it. There’s ones I’ve started to do, which are these ones here,” he says, pointing to a couple of pallets of engine cases. “It’ll take the form of a 1600 or in a dumbed-down form of what you would have seen in the Daytona bike.

“I think there’s demand, because it’s what I see myself. Like with cars, Mercedes doesn’t make a V8, they’ve canned all of those, and I bought the last one last year because I knew that was coming. You can go and buy an electric car, but they haven’t got any soul, haven’t got any spirit, and I can sort of see that with bikes in a way. Someone will want a big musclebike to have a bit of a play on.

“We’ve got the superbike-spec K-Tech suspension and the Dymag carbon wheels, and we’ve already got that to do the first one. We’ve just got to do it.”

The legacy

But something tells me their hearts aren’t in it. If Ken and Barry Horner wanted to churn out mediocre machinery to appease the cashed-up public, they would have done it years ago. And, like everything they do, with resounding success.

“Look, it needs to go somewhere,” concedes Ken. “Where it ends up, I don’t know. If someone came

in and said we’d like this and we want you to project manage, and then take it to another level, then that’s okay.”

But ultimately, these guys just want to be able to go racing. And the loss of the Island Classic weighs heavily on them because of the highly competitive stage it provided on which they could genuinely test themselves and their machinery.

“If it comes back one day, we’ve still got bikes we can run in that because they were a level above the old Period 5 class, with better wheels and brakes and things,” beams Barry. “Sure, you produce more power, you produce more issues.

“But that’s the challenge: three steps forward, two steps back, but you never stop. It’s what gets you out of bed in the morning.

“It’s just serious bloody racing, and that’s what we like doing.”

Words Kel Buckley + Photography Janette Wilson & AMCN ARCHIVES