A new set of patent applications penned by Marco de Luca, the project leader of Aprilia’s successful RS-GP MotoGP bike, suggest the high-tech Aprilia aero which adorn the prototype might be soon appear at least in some form on the firm’s future roadbikes.

Because patents are intended to protect the commercial interests, and any attempt to lock-in a competitive advantage using patents might be seen as unsporting by the FIM, there’s every chance these new applications are an indication Aprilia has ideas to use the concept on production bikes in future. The patent says the invention “relates to motorcycles cooled with water or with another liquid coolant and equipped with a fairing, for example, but not exclusively, racing motorcycles.”

What’s more, the latest generation of Aprilia’s RS-GP – evolving from a ground-up redesign in 2020 – has dimensions and curves unlike either its rivals or anything from the past and these patents give real insight into why the bike’s design differs from all its rivals and how that unique approach is delivering results.

So, what’s the trick?

As we’ve seen from the proliferation of winglets on GP bikes and their showroom spin-offs in recent years, there’s a new focus on downforce in motorcycle design. For decades the aerodynamic targets of motorcycle designers have been stability and drag reduction, but the addition of any substantial level of downforce is relatively new

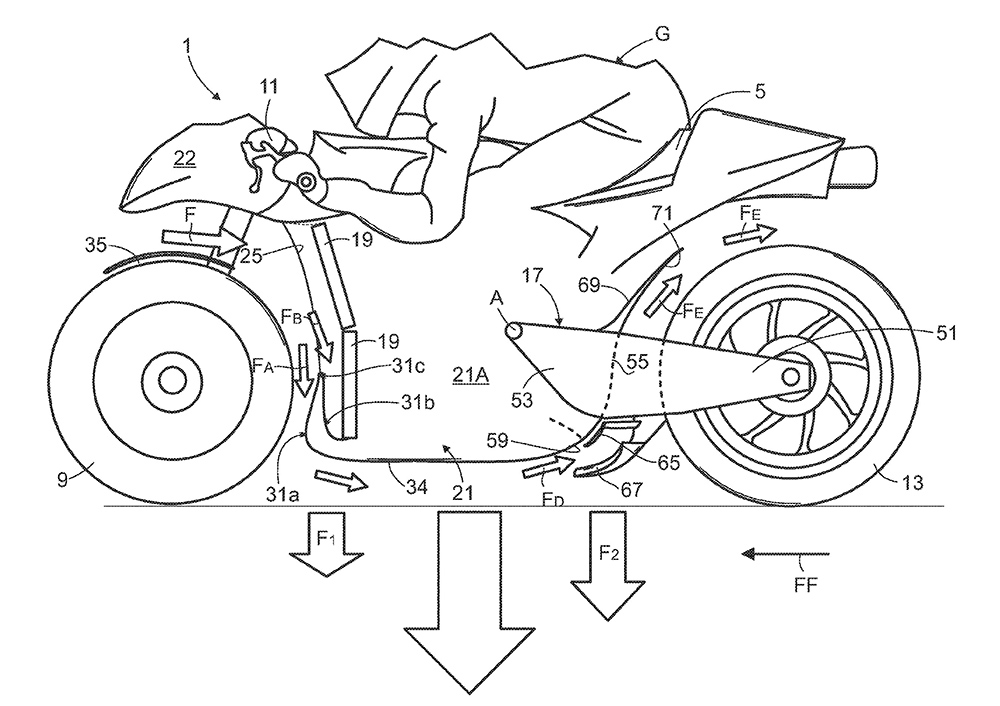

So far, the development of downforce has mirrored the way it emerged in F1 cars decades ago: in the late 60s cars sprouted tacked-on wings, but into the 70s the bodywork itself started to create downforce, initially with wedge-shaped cars and later with ground-effect underbodies. Most GP bikes are still in the ‘tacked-on wings’ stage, but Aprilia is evolving towards a more holistic approach

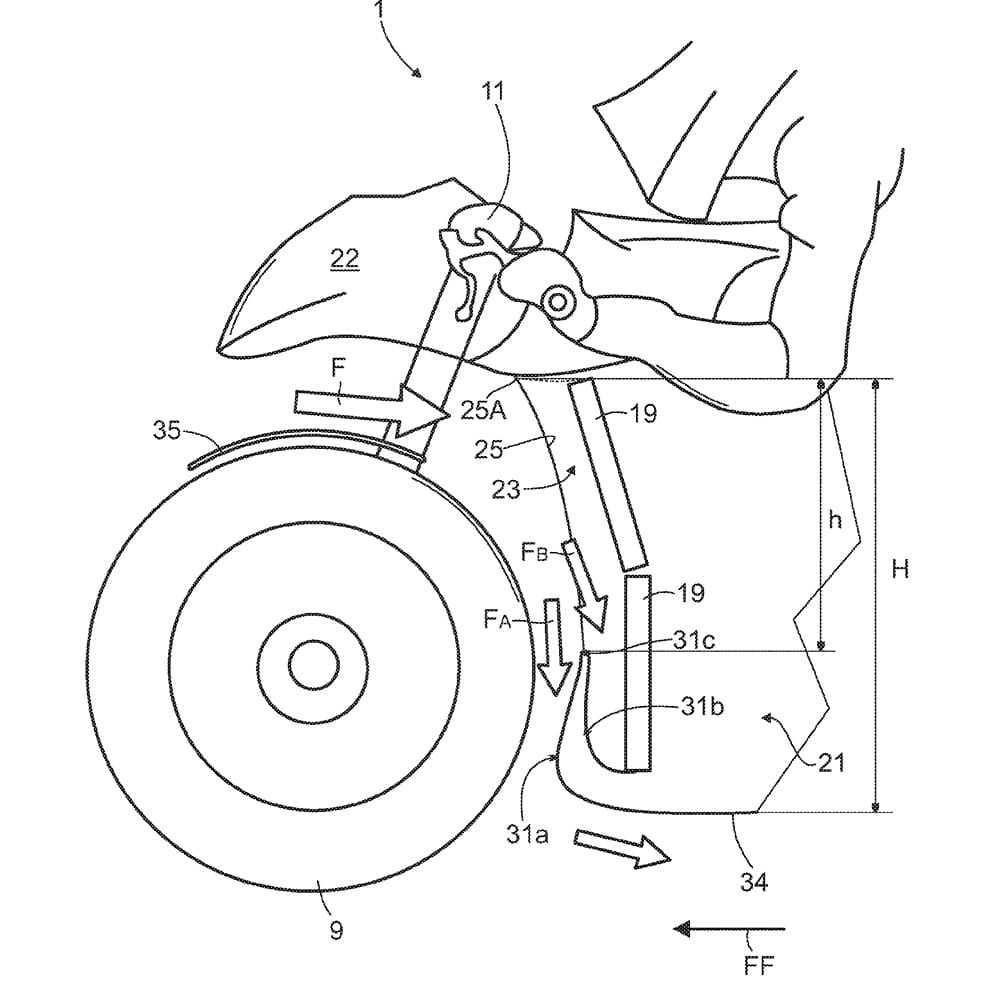

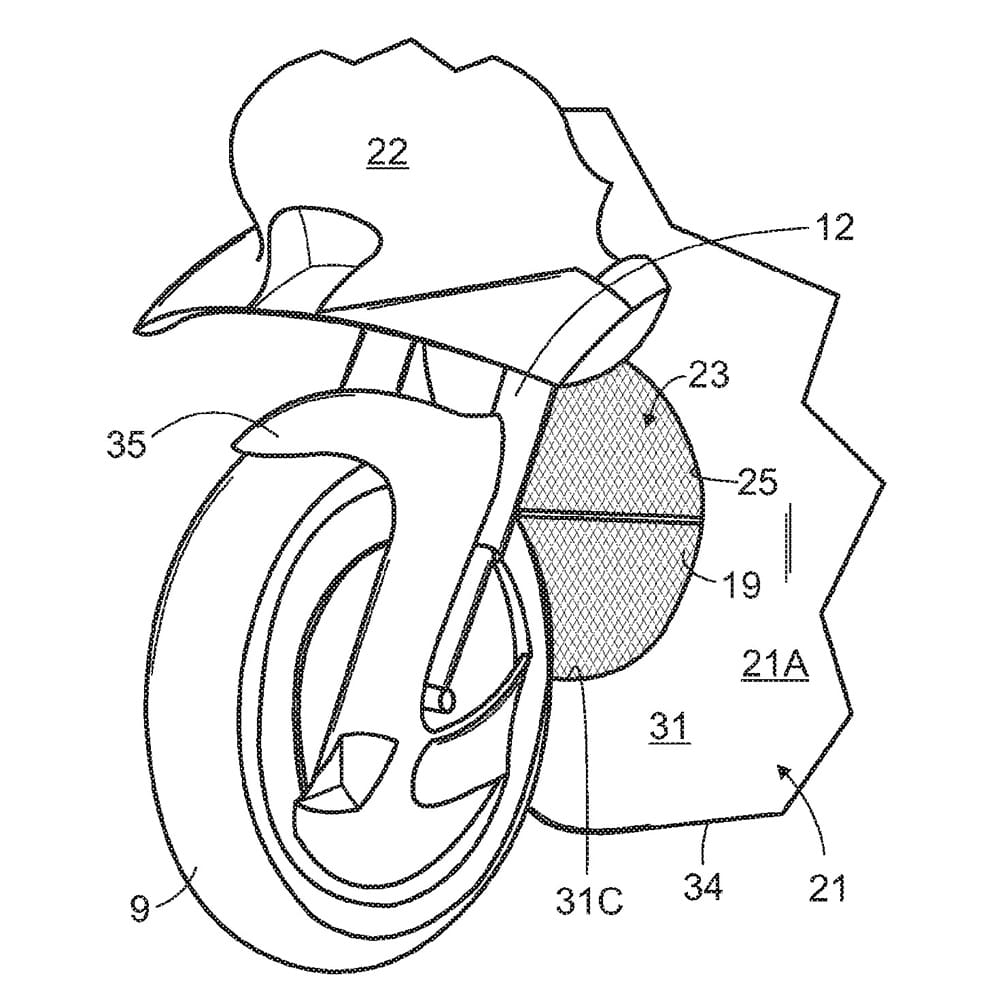

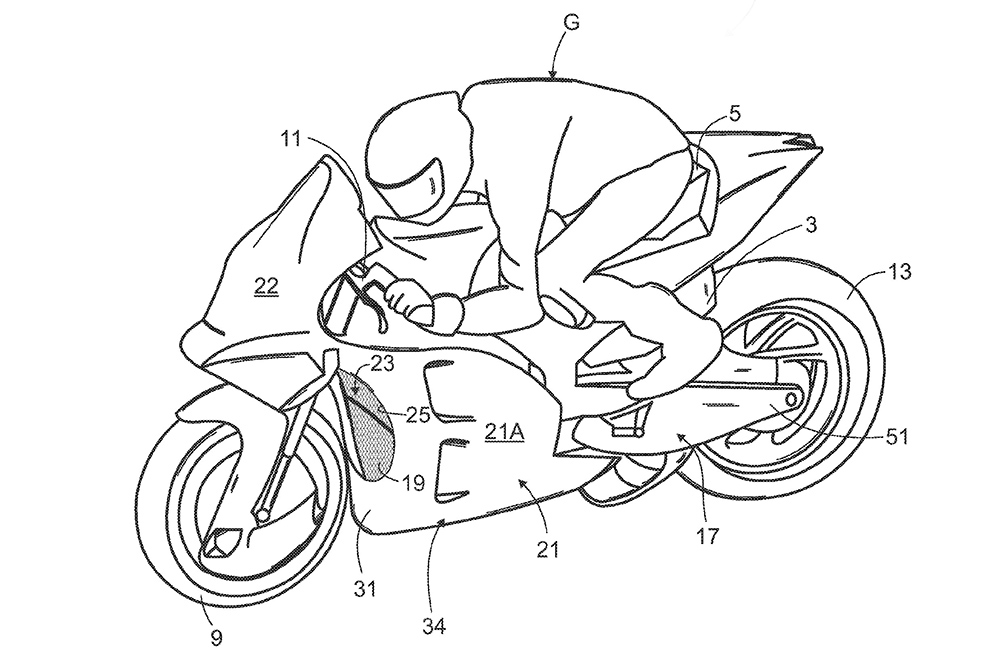

The new patent applications ignore the wings entirely and focus on a body design that manages a triple-whammy by reducing drag, improving cooling and adding downforce. Starting at the front of the bike, the first noticeable difference between the RS-GP and its rivals is the visible gap between the front wheel and the fairing: it’s huge. That high nose and set-back bodywork gives the bike an ungainly look, but plays a key role in the aerodynamic concept.

Air that would usually be deflected over or around the nose is instead encouraged into the gap above the wheel, where it’s channelled towards the two radiators needed to keep the 1000cc, 90-degree V4 cool. Excess air that can’t go through the upper radiator is funnelled downwards towards the lower one and one of the Aprilia’s key innovations – a bulb-like shape in the chin of the bellypan.

This rounded section of bodywork actually covers around half the lower radiator and its upper edge acts like a blade, slicing the downward-moving airflow, with half deflected into the bellypan and the rest channelled out under the bike. The air deflected into the ‘chin’ is slowed down by a tapering gap between the ‘chin’ and the radiator, increasing pressure to help force it through the rad and to create a high-pressure zone above the bellypan.

In comparison, the airflow running under the bike’s bellypan is accelerated by the shape of the bodywork, lowering its pressure. With higher pressure above and low-pressure air underneath, the result is downforce generated by the shape of the belly.

Although not shown in these patents, Aprilia has since added extended sides to the bodywork that align with the ground during corners, creating a ground-effect style surface to increase downforce at extreme lean angles.

What’s going on at the back?

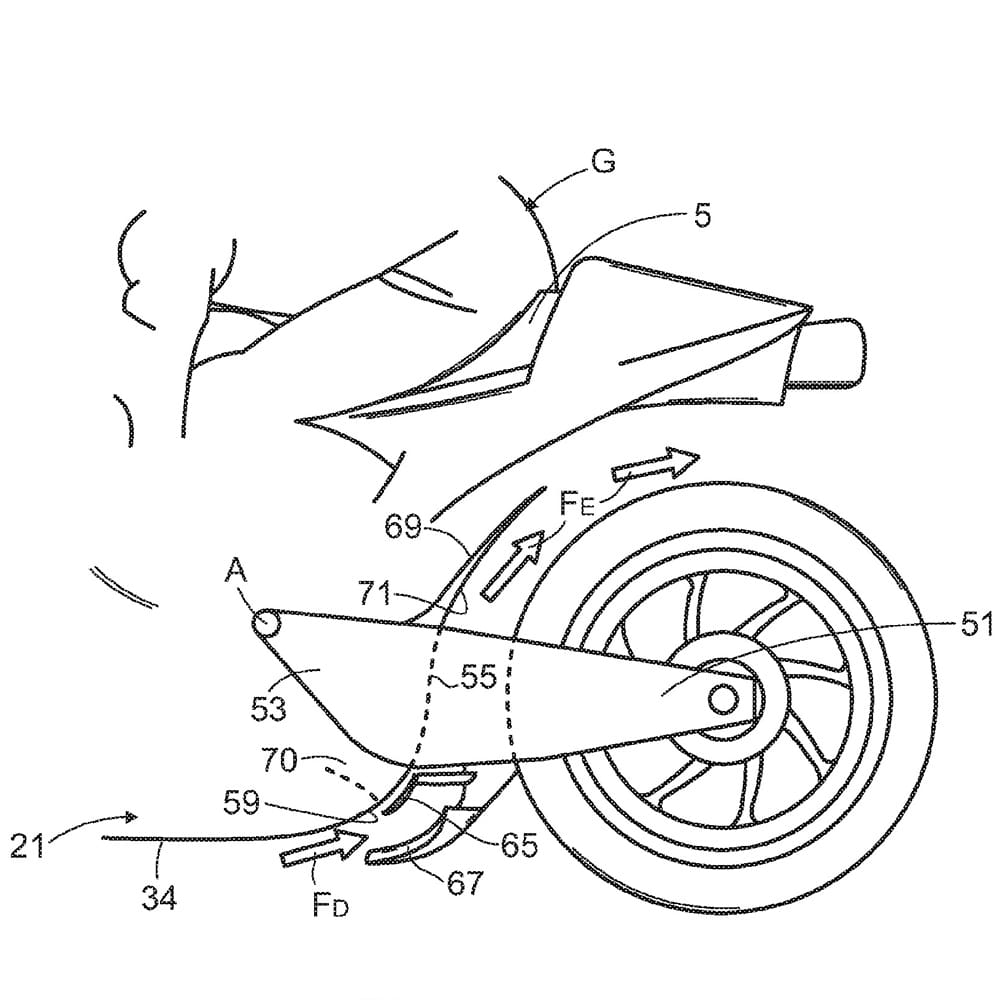

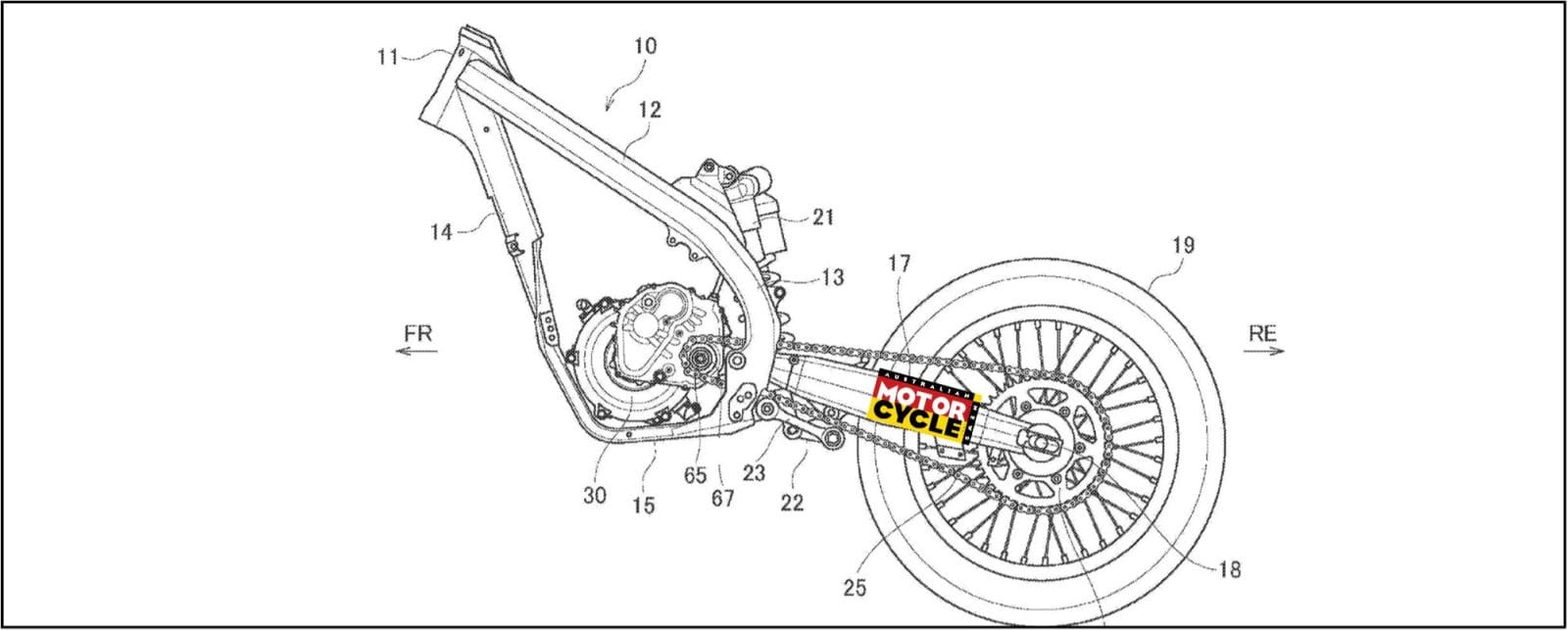

Although the scoop-style deflector attached to the bottom of the swingarm is something we’ve seen on rivals before, initially appearing on the 2019 Ducati, the Aprilia design appears to integrate the idea more completely with the rest of the bike.

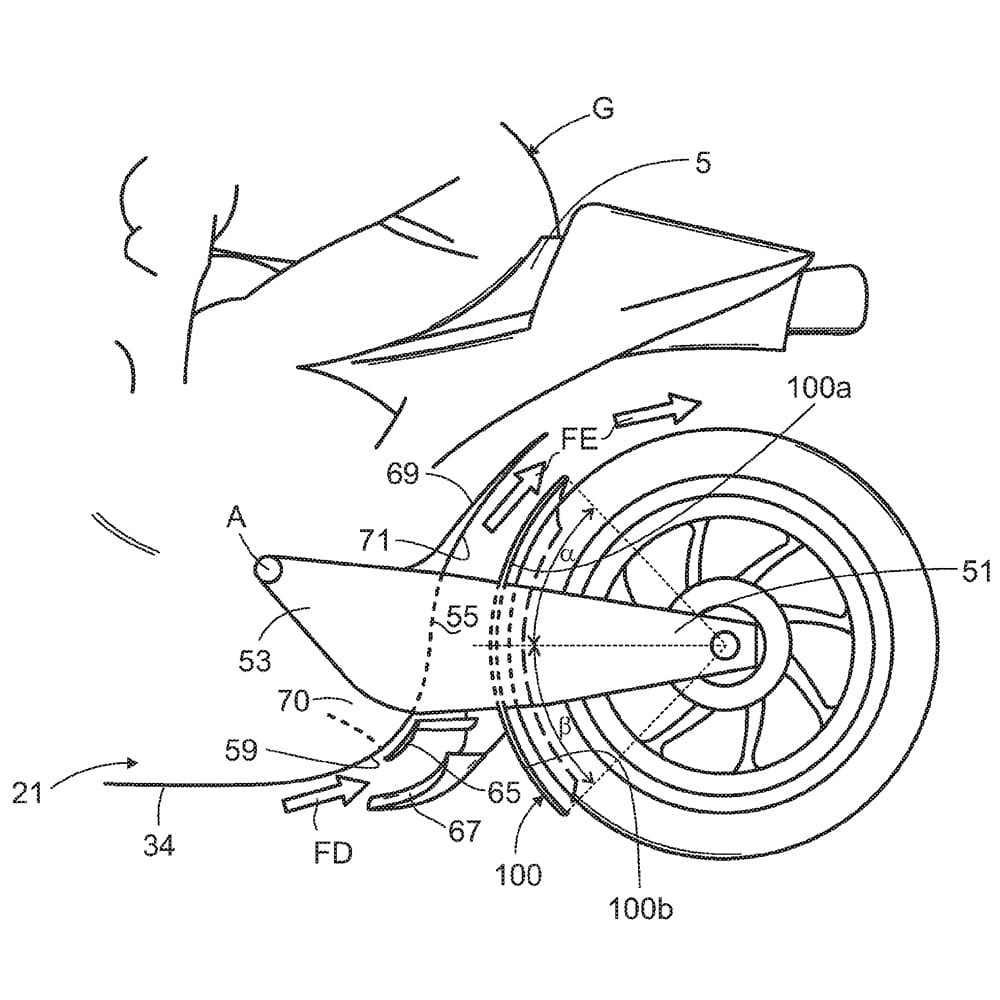

Look at rival GP bikes like the 2022 KTM RC16, which also has a swingarm-mounted spoiler, and usually their bellypans come to a distinct end at the back. That’s not the case with the RS-GP. Instead, its belly swoops upwards and blends into an unseen channel through the front of the swingarm, ahead of the rear wheel, drawing air upwards with the help of that scoop-like swingarm spoiler. The air then runs through the rear ‘hugger’ which does anything but hug the rear tyre – it’s a long distance away from the rubber to create a channel for the air to go through.

“This flow channel provides an efficient guide for the air flow generated by the forward movement of the motorcycle, a reduction in aerodynamic drag and an effective cooling on the rear tyre,” the patent reads. “Acceleration of the air flow around the rear portion of the fairing toward the rear surface… [inside the rear mudguard] …causes an aerodynamic effect with a force directed downward, which increases the ground adhesion of the motorcycle.”

So once again faster-moving, low-pressure air is creating downforce, this time at the rear, assisting the downforce created at the front of the bellypan.

An additional element, shown in another drawing in the patent [fig.10 – where it’s marked ‘100, 100a and 100b’] can be optionally added as a close-fitting hugger inside air channel, protecting the rear tyre. The idea is that this component is fitted only when it’s wet or cold and tyre temperature needs to be maintained rather than reduced by cooling airflow. The inner ‘shield’ is made of two sections that overlap, allowing its overall size to be adjusted to tailor the tyre temperature. Interestingly, and perhaps pointing to future non-racing adaptions of the idea, the patent says that the adjustment is manual but could be automated in other bikes.

“For this purpose,” the patent says, “An electric, pneumatic or hydraulic actuator can be provided. It would also be possible to control lengthening and shortening of the shield by means of a mechanical control with an operating member positioned on the handlebar or otherwise accessible to the driver during riding.”

Such a system would probably be illegal under current MotoGP rules, but if a production bike was fitted with such a device it might be allowed to be used in WorldSBK, where active aerodynamic parts are legal provided they’re fitted as standard to the homologated road version.