Like thousands of Aussie riders, Andrew Pitt’s path to international road racing was via dirt track. As soon as Pitt was allowed to he went road racing, on a Honda NSR250 roadbike, then a Suzuki RGV at NSW state events, before moving up to nationals, then Aussie Supersport riding Kawasakis.

After some high-profile domestic results, Pitt met a character that would have a great influence and impact on his career, namely Peter Doyle, currently the CEO of Motorcycling Australia.

“Still the best team manager I have ever had,” Pitt said about his time with Doyle. “I guess I got spoiled. You knew how to do it, you knew where you stood. He knew how to run a team and put the right people around you.”

In 1999, after finishing second the year before, Pitt was the only rider in any class with official support from Kawasaki Australia. By then the aim was to follow the heroes he watched on TV growing up and go global, albeit in production-derived racing. In a combined pre-season test with Harald Eckl’s official WorldSBK factory squad, Pitt was initially quicker than both works riders.

From then on, with Doyle pushing from one end and Eckl pulling from the other, Pitt got his first season of WorldSSP racing in 2000 as teammate to Iain Macpherson, the Scotsman who had come so close to winning the title the year before.

It took Pitt a year to learn, and a tough year, too, he remembers, driving round in a small motorhome with a big map, helped to acclimatise both on and off-track by Macpherson.

“He was great, he took me around, showed me around, let me follow him in every track we went to – which he didn’t need to do,” said Pitt. “I will be forever grateful for his help. Without his help, I would have really struggled. Hockenheim, Monza first time…? I had no idea how to go around those tracks. The only slipstreams you had in Australia were at Eastern Creek and Phillip Island.”

The 2001 season provided the first of Pitt’s world championships. Six podiums on the way, but no race wins, much to Pitt’s annoyance. Yet, as he remembers, “We got the big trophy at the end of the year.”

Race wins eventually came in 2002, but no second championship for Pitt, but yet, amazing as it sounds now, he went straight into a Kawasaki MotoGP ride the year after.

“I had a two-year contract but then the political games came out,” recalls Pitt, something he would suffer with from then on in. “We did a year on the bike. It was Kawasaki’s first concept MotoGP bike and they really struggled to get their heads around what they had to do. We had Dunlop tyres – the only team with Dunlop tyres.”

But there was no year two.

“Through political manoeuvres, TV, Eckl wanted a German in the team, you know how it works,” said Pitt.

A few Moriwaki rides in MotoGP and three races for Yamaha Italia in WorldSSP in 2004 and the underemployed Pitt returned to the WorldSBK paddock in 2005, now on a Yamaha Motor Italia YZF-R1 Superbike.

In what was his first Superbike season since leaving Australia, he finished eighth overall and went back again in 2006, winning one race at Misano, taking six podiums all in, and finishing inside the top five. But then he was suddenly out of a ride for the 2007 season.

“I probably had too much trust in the team manager and guys like that at Yamaha,” he says. “I fully believed that I needed another year. We had just got the bike to a good level. I won a race and [Noriyuki] Haga only won one race that year. That was really frustrating, probably one of my biggest disappointments.”

Left with no Superbike to ride, Pitt was thrown a lifeline – a short and fragile one as it turned out – as he went and tested the Ilmor 800cc MotoGP prototype.

“We did one race, the bike broke down and that was it, game over,” said Andrew.

A temporary halt to the racing as such, but not for another memorable on-track experience that would add to the vast array of knowledge and understanding that Pitt is now making use of as his role of Crew Chief for Andrea Locatelli in this year’s WorldSBK Championship.

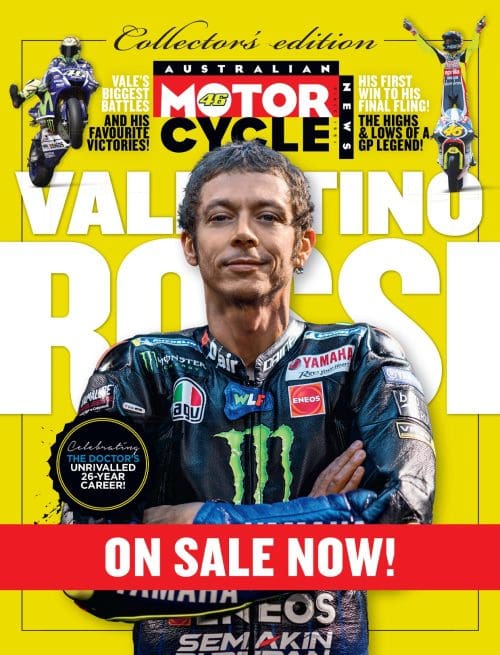

“I got a call up that year to be a test rider for Yamaha MotoGP, and Michelin, when it was Valentino [Rossi] and Casey [Stoner] battling with Michelin and Bridgestone the whole year. We were testing tyres every week in Spain, Germany, Japan. We would find something and they would make it and get it to Valentino for Sunday morning.”

Pitt, then 28, still wanted to race, and when Sebastien Charpentier broke his hip, he was granted two wildcard rides in the Ten Kate Honda WorldSSP team.

Pitt was actually supposed to have ridden the Ten Kate Superbike in 2008 but Carlos Checa was finally chosen to ride the Honda, and Pitt was asked to ride WorldSSP for one more year.

“You win the championship, you ride a Superbike,” recalls Pitt.

“Jonny [Rea] was my teammate.”

Pitt could see how good Rea was from the first test together, and Rea recently conceded it was Pitt who highlighted the importance of fitness and who helped turn him into a true professional racer. Although according to Pitt, it took a long time to get through to Rea.

And after the positive influence Macpherson had on Pitt’s past, he felt he had to help the ‘new boy’ Rea along a bit.

“I saw that as a role too [after] Iain had done it with me,” said Pitt. “Every little thing you can do to make life easier for him, it helps, for sure. I had had that courtesy done to me. Jonny and I worked completely together in the practice sessions, even though we were fighting for the championship.”

But despite Pitt winning his second WorldSSP championship in 2008 – on a different make of machine from his 2001 success, remember – Rea got promoted to the Superbike in 2009 and Pitt had to stay in WorldSSP. “We both should have been on a Superbike in 2009.”

After a poor 2009 when a new bike came along and the suspension supplier changed in a way that did not work out for him, Pitt was out of a ride for 2010. A chance to ride in WorldSBK from the Reitwagen BMW team drew Pitt back into his favoured big bikes for the 2010 season, but the team lasted just a few rounds, then folded.

Defecting to the British Superbike Championship and riding for the Motorpoint Yamaha team for a few rounds proved to be another misstep.

“It was the bike that Neil Hodgson ended his career on, and I did the same, one corner later, on the same track,” is how Pitt put it, so succinctly.

Nerve damage in his arm and the prospects of ever-worsening offers did not appeal to him.

And just like that, after a decade of world championship racing and testing, it all came to an end for a rider who had ridden or raced almost every kind of four-stroke of that era.

So what do you do after your racing career has come to a sudden halt? Being a crew chief was not on Pitt’s radar at that time, even though Pitt felt he was quite good at developing a bike: “you could work it out,” he says. “Just work through it in a methodical way.”

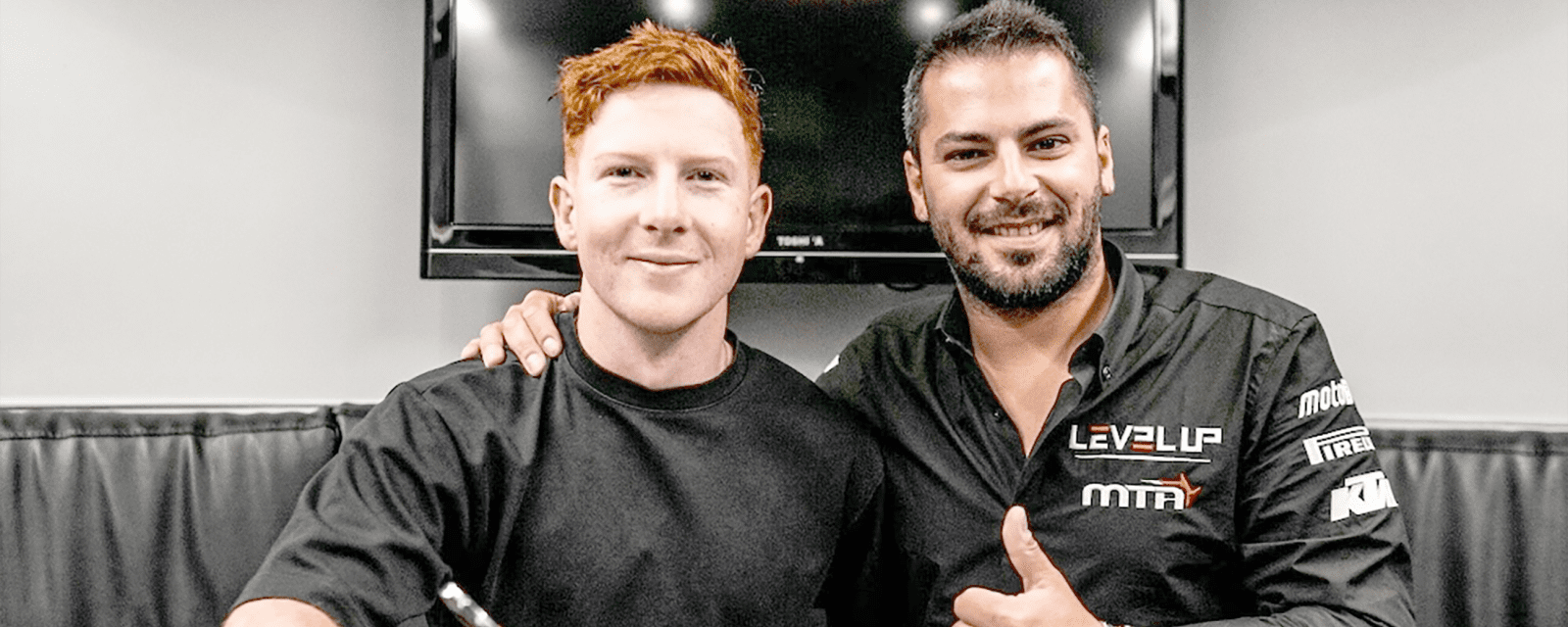

Then a phone call out of the blue from UK team owner, Nick Morgan, changed that, he said he needed someone to come and help out English racer Gary Mason as a crew chief.

“I think he got a podium first time out at Knockhill, then he got a few more podiums and it kind of turned his season around,” said Andrew. “I really enjoyed trying to get the best out of the bike and the rider and I learned pretty quickly a lot of it is a psychology job with the riders. That is what the main part is.”

He has since worked for teams running Fabien Foret, Romain Lanusse, then PJ Jacobson, Randy Krummenacher, then Alex Lowes and Michael van der Mark last year before being teamed up with Locatelli in 2021.

“I really considered long and hard to go to BMW with Michael [this season], just because of the relationship I had with him. You do not find that a lot of times.”

But he stayed with Yamaha because of the group of people put together inside the Yamaha garage, which he sees as a long-term project.

What Pitt agrees is that no matter how vast his vault of experience is, ex-rider crew chiefs can never tell the rider how to ride. It is still his approach now with his rookie-of-the-year rider, Andrea Locatelli.

“I can get comments out of a rider if he is having trouble explaining something,” said Pitt. “I can still put myself on the bike and say, ‘do you feel this or do you feel this?’ I would give him options. I will show him differences and he is smart enough to work out that if Toprak is doing this and this and I am doing this and this, and I am slower, there it is, all laid out in front of you.”

But Locatelli is not your average rookie, in one of the series’ most competitive seasons in recent years, he’s fighting for a top-five overall finish and with four podiums heading into the final round in Indonesia.

“I liked his work ethic from day one,” said Pitt. “Obviously we saw his ability last year in WorldSSP but you never know if that translates onto a big bike. We saw in testing he did the typical thing; too much corner speed and didn’t open the throttle on the exits, riding the bike like a 600. But there were flashes. In the second round in Portugal, he finished fifth. A lot of it was me convincing him that because we had changed the gearing on the bike we had made it easier for him to use. Away he went.

“He also had pressure from behind the whole race, but he finished fifth, and had Toprak in sight, three or four seconds down the road. That was the first sign that this kid was going to do it, and we just had to get it out of him every weekend. We also saw what his strength was – when we made him do a lot of long runs in winter – that he could just go out and do the same lap time to the tenth of a second for 20 laps. He had to work on his initial pace, which was there. We saw him in the early races in the first few laps getting beaten up with bikes diving up the inside of him. That all can happen.

“I will put my hand up and say that I thought it was going to take him longer. I thought if we could have got him to where he was at Assen (on the podium, at Round 5) by the end of the year it would be job done.”

Pitt puts Locatelli’s apparent over-performance down to the atmosphere and the support he’s given by the team in the garage.

“I think the biggest thing for him, something that he lacked in other teams in Supersport and Moto2, was to probably feel the support of the group around him. That is the thing I work the hardest on; keep the rider involved all the time, give them feedback from an event, show them some data, this is what you can work on next time. He says he really feeds off that.

“At the start he wanted to know all the numbers, what spring was on the bike… and he tuned himself to a standstill. Now, we don’t tell him one thing we have done on the bike. We might say, ‘Oh, Christian has given it a little less power in third gear, see how that feels’. Or tell him I have done something on the rear of the bike to improve stability on braking. See what he thinks.

“He is four or five times as relaxed as he was at the start of the season. He doesn’t want to know because we have done all the work behind the scenes just to give him the best bike we can on the track. We are never going to get it right 100 percent of the time but if we work together as a group, test tyres, work for the race on Saturday, we generally get there.”

Pitt came up to me after the bulk of this interview had been completed and said that he wanted to not just underline how much of a help his father has been through his career, and how much he appreciates it all, but how he had wished he had listened to him more often. Many people can relate to that, I’m sure.

Andrew’s own approach to the current job in hand, I put it to him, is almost paternalistic. A firm boss but also a confidant to the rider and all in his part of the Pata Yamaha with Brixx team.

“Sure, 100 percent,” said Andrew.

“They need reassurances off me. They know they can always come to me but they know also that this is what needs to be done and there are no grey areas.

“We know how to have a beer together but we also know exactly what is tolerated in this corner of the garage, and what to do before a session, during a session. I don’t even have to speak to them now, they are so well oiled as a machine.”

My final question, based on Pitt’s own comments about the best team manager he ever had when he was a rider himself. “How much,” I asked, “are you, consciously or otherwise, trying to be Peter Doyle?’

There was no delay in the answer.

“Well, he was my best-ever example,” affirmed Pitt. “He had the most respect out of team members I have ever seen. Everyone knew where they stood, no-one took the piss, there were no snakes around because they wouldn’t have been there. You have probably hit the nail on the head. That was my best example and if I can command that sort of respect that Peter had, and get those sorts of results, I am on the right path.”