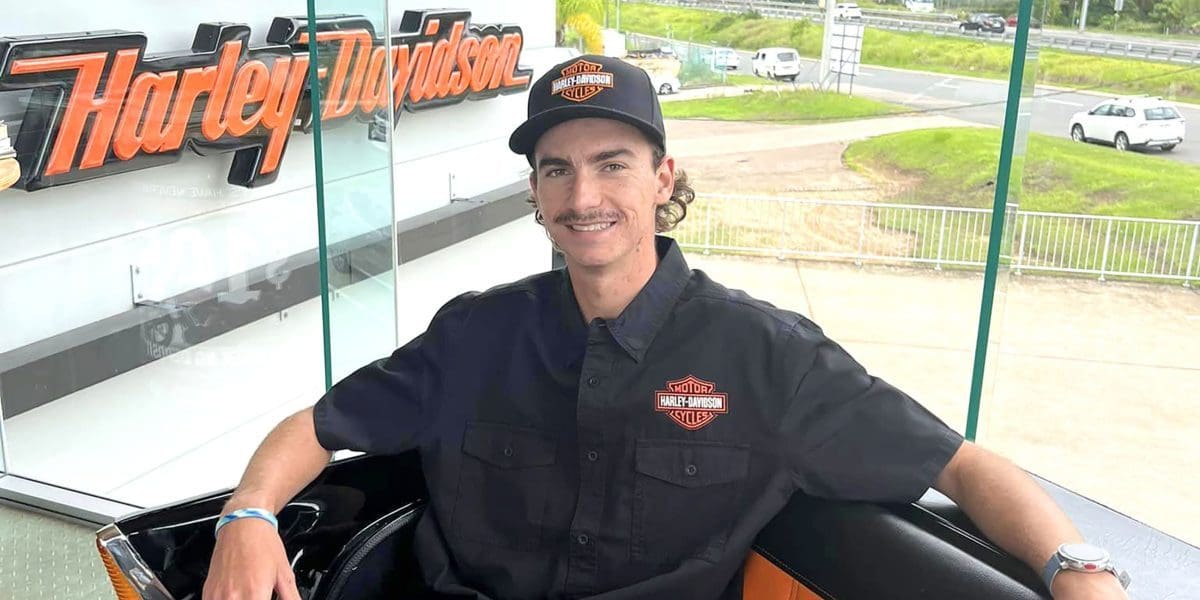

We grabbed a word with the kind and calculative MotoGP veteran, Andrea Dovizioso.

There’s no dressing it up. The latest – and the last – career foray has not gone to plan for Andrea Dovizioso. The veteran Italian, who has racked up a world championship and 15 premier class wins across a decorated 21-year stay in the grand prix paddock, had visions of fighting for race wins and more when he returned during a career sabbatical last September.

Instead, the 36-year old has been reduced to a bit-part player in a series where he used to have a leading role. His struggles aboard the 2022 RNF Yamaha YZF-M1 have been so bad that he’s claimed just 10 points from the first 11 races. Coming home 20th at Mugello left Andrea Dovizioso to conclude this will be his final year in MotoGP.

“Unfortunately, in recent years MotoGP has changed profoundly,” he said during his announcement to call it quits at the conclusion of the Italian GP in Misano. “The situation is very different since then: I have never felt comfortable with the bike, and I have not been able to make the most of its potential despite the precious and continuous help from the team and the whole of Yamaha.”

It’s been tough to watch the figure who pushed Marc Marquez hardest between 2017 and 2019 struggle in such fashion. Across the past six months, there have been no real signs of progress, and only a few fleeting moments when he claims to have felt comfortable, more natural aboard a bike which requires a polar opposite riding technique than Ducati’s Desmosedici machinery, over which he presided for eight years. As of the summer break, Andrea Dovizioso had failed to finish closer than 27 seconds to the race winner – an eon to a man of his pedigree.

But long before our conversation, Andrea Dovizioso had come to accept he would never be capable of riding Yamaha’s particular 2022 M1 like current championship leader Fabio Quartararo.

“You can’t ride in an instinctive way. It’s becoming a more irrational way to ride, and that’s not so good. But it’s the reality. You can’t change that enough,” he told AMCN. Yet rather than feel bitterness or anger at the situation, the 2004 125cc World Champion is philosophical.

“On one side I think everything you do, no matter which way it ends, is always experience. You have to try to always take – it’s not about positives, but experience. When you are not in the situation you want, a lot of important things happen which are very important for your life, to understand what you want, what you don’t want, what you have to do in a different way. That means trying to analyse and understand.

“For sure, this is not what I want – 100 percent. But if you start to look a lot at careers of top riders, many times similar situations happen.”

This is Andrea Dovizioso to a tee. A rider not blessed with the obvious kind of otherworldly talent of a Marquez or a Casey Stoner. But one whose analytical eye and methodical working method was as big a factor in Ducati’s MotoGP revival as was his obvious speed. It was believed he could perform a similar job with Yamaha – a factory for whom he enjoyed success as a satellite rider back in 2012 – by helping engineers turn the M1 into an accessible machine on which riders other than Quartararo can win.

But he’s found the factory unwilling to make changes to his liking, with Quartararo’s needs very much the priority. Has he found the Yamaha factory in 2022 similar to what he experienced in 2012?

“I think it’s exactly the same – very, very similar almost everywhere,” he said. “The difference is MotoGP changed in the way manufacturers look at and develop the bike. In this moment just Yamaha is able to still achieve important results. But I think this happened because the relationship between Fabio and Yamaha is so special. They are able to fight and win the title, not because the pace of the bike is good enough for most of the riders.”

“There are important developments. Especially the European manufacturers become more aggressive, stronger and they have good money to invest to try and make a better bike. They invest a lot in former riders so if you look in the last five or six years, apart from who won the title, MotoGP changed a lot. The Japanese bikes are not any more that much better like than the past.”

Dovizioso’s career swansong could have been so different. After walking away from Ducati early into the 2020 season, he tested Aprilia’s RS-GP three times last year. Despite the Noale factory’s advances, he never appeared convinced to become part of that project. During those tests, could he ever have foreseen Aprilia and lead rider Aleix Espargaro putting together a season that has them right in the thick of the title fight?

“Immediately when I tried the bike last year, I explained the base of the bike is really good. When you have a good base, it’s not that difficult to arrive with results if you work in the right way. At the end, what Aleix and Aprilia are doing now is special,” he said. “I think it’s a good example like what Marc did with Honda, what Fabio’s doing with Yamaha, what I was able to do with Ducati for a long time…

“It’s about your riding style being good for the characteristics of the bike, and year by year you can just use that potential more. You get used to the bike and you don’t have to think too much because you’re riding in an instinctive way.”

Talk turns from present to past. Now his retirement plans are public, Andrea Dovizioso seems content to look back on some of his finer achievements. And from a storied career that spanned 21 years, there were plenty to discuss. A 125cc world championship won at just 18 years and 201 days of age in 2004; six podiums aboard a satellite Yamaha in 2012; finishing runner up in the MotoGP World Championship for three years running with Ducati. Yet, it was 2017, when he took the championship fight all the way to the final race of the year that he ranks highest.

“Yes, 2017 was crazy,” he said. “When you don’t expect a really good season and you are able to win six races in MotoGP in the same year, that’s something big. That season, I finished second and the championship finished in the last race, even if we couldn’t really fight against Marc in the last race. I didn’t feel I lost the championship in Valencia. I was really happy about that season. That was the nicest for sure, even if in 2018 I was a bit faster.”

It’s hard to state just how bad Ducati’s MotoGP machine was when he joined in the winter of 2012, and the disarray its racing department was in. For him to play an integral role in the factory’s renaissance made his performance in 2017 all the sweeter.

“When you complain a lot and you’re a lot of seconds (behind) at the beginning and there is no way to be competitive, but year by year, when nobody had a different option. Ducati didn’t really have a different option. I didn’t really have a different option. That gave us the possibility to work so hard to try and arrive at that level. When you are able to achieve that, it’s something big, deep, (that came from) years and years of working from home, during the weekend, during the races with a lot of risk… That was nice for sure.”

One of the factors behind his choosing of 2017 was due to whom Dovizioso came up against. There was no doubt the Italian faced the strongest version of Marquez. Their numerous last-lap battles, with races decided on the last corner, quickly became the stuff of legend, not only because of the frequency of them – six across three years; but because of who won the majority. Yes, the championship order was Marquez first, Andrea Dovizioso second in 2017, 2018 and 2019. But the Italian was victorious in five of those six last-lap showdowns.

And all the while relations between the pair remained cordial, friendly even. How was it so? “From the beginning, I approached the battle with him with that mentality (remaining friendly),” Dovizioso recounted. “I already knew he was like that. I mean, I’m studying a lot the other riders. So, I knew every detail from him. I wasn’t surprised when I started to battle with him, to see his aggression. I already knew (this) and that’s why I was able to beat him more than one time because I was approaching him with a strategy. I was thinking a lot about what I could do; it wasn’t just about trying to beat him in (a certain) corner.”

“Nothing happened between us for two reasons. First, because I approached the battle in a different way to all the other riders. Second, because fortunately we were a bit lucky. We were battling hard and something bad never happened – close to the limit, but not bad enough to start fighting. So, this is the reason why we always kept a relaxed relationship.” So, it was a case of trying to beat Marquez with kindness? “No,” he retorted. “The point is if you know the best point of the competitor, you can’t fight in the same point. Where most other riders try to do that and lose. In my opinion, that’s not smart.”

While friendly, honest and humble in conversation, there could be no doubting Andrea Dovizioso was a fierce competitor. I first recognised the true extent of this trait early into 2017, when he voiced frustration during an interview over how some of his best rides until then had gone almost unnoticed.

“Many times when I make a result some other riders think it’s easy to do,” he told me, before that year’s title challenge had kicked into gear. “From the outside it doesn’t look like I did a really special result. But when I’m inside I can say that it was.”

Fast forward to 2022. Does Andrea Dovizioso now feel like he has received suitable recognition as one of the sport’s top riders of recent times?

“When you don’t make a good result it’s so easy to understand what the people think,” he said. “This year has been like that. And it’s been so nice to see a lot of fans in every country cheer for you because the battles between me and Marc and battling for the championship for three years remain as something to them. I think it was very emotional for everybody who was with me or against me. Everybody wants that.”

“I think the MotoGP we’re living now is a bit different. If Pecco (Bagnaia) or Fabio wins, normally it’s not with a battle. And that’s not so nice. In that way we fought, we battled, it was something… not unusual, because it happened in the past, but something nice. Everybody wants to see that. And this (memory) remains (with fans). That’s good. To be recognised as one of the best in the championship? No, I don’t think so. One of the good (riders), yes. But that’s not too important.”

Never mind the race wins, last-lap battles and the single world championship victory. One of his finest achievements was the sheer scale of his career. In the history of the sport only Valentino Rossi started more races than the 343 Dovizioso is currently on. He also holds the record for the highest number of consecutive grand prix starts (325). Sixteen years and 20 days separate his first and last GP victories, the third-longest winning period in history, behind that of Rossi and Loris Capirossi.

Present day feels a long time away from the 3 June 2001, the day on which a 15-year old made his grand prix debut at Mugello. What’s been the biggest change in the 21 years since then?

“What changed a lot is the way you have to ride the MotoGP (bike). if I just compare 2008, my first year in MotoGP, to now, the bike changed a lot. The way the rider has to ride is changing a lot. In the way you have to work during the weekend changed a lot. The kind of people you have to work with changed a lot. That is a huge change. I don’t want to say it’s bad, like a very old person! But you have to ride in a different way (and) you are always less under control about most of the things on the bike.”

“In the past, it was different. That’s why in the past there were always the same riders on top. More or less, you found a way to be competitive with a manufacturer, (so) every situation you would be competitive. Now, no. Now you are related a bit more to the technical side. If you are not adapting 100 percent to the technical part of the bike, you are not able to use the potential. Half a second and you’re at the back of the group. That is the change of MotoGP. I’m not complaining but this is the reason why this happened.”

Looking ahead, what does the future hold for Dovizioso post-MotoGP? After the Barcelona GP in June, he didn’t exactly rule out quitting before the end of the season. Asked if he’d be on the grid after the summer break, he enigmatically answered “I think so.” And while that remains true, it will be only for three races. But what will he be doing in 2023? An avid MXGP fan, could he foresee himself working in a motocross paddock? Or perhaps remaining to work for a MotoGP team? Or assisting younger riders?

“I’m in a transition mood! I have a really clear idea of one project but still it’s not there,” he said. “Until it’s not there, it’s done, you can’t be sure. About work or having some position in this world, at this moment I’m a bit stuck because I think I can have more than one important position. I have a lot of experience. But in this moment, after 20 years, and living what I’m living, at this moment I don’t have that fire inside of me to do something. I’m receiving a lot of proposals but in this moment, I think I need a bit of time to not work in this world. When you decide to do something, you need to believe it. You have to feel it. You have to feel something inside, that you’re doing something because you want to do it. So, I don’t know.”

“I’m completely open. From an old 36-year old I know that every time you say, ‘No, I’m never going to do that’, it happens (laughs)! So, I don’t want to say, ‘No, I’ll never do that’ because year by year life changes, especially from a rider’s side, especially when you do really important things for 20 years and everything is around this. You have your idea. But when that changes, it’s a big change.”

“So, you can’t really know all the details and if something will change in your mind. Everything is possible. Everything! Or I will come back to race after 40… Never say never,” he laughs.