Aldo Drudi studied fine arts on the very ground the Italian Renaissance erupted in the 14th century thanks to the likes of Leonardo da Vinci and Galileo Galilei. That period of cultural change, mixed with being raised on the Adriatic Coast, which is also home to motorsport icons such as Benelli, Bimota and the Misano circuit, played a key part in the life and works of MotoGP’s most famous artist.

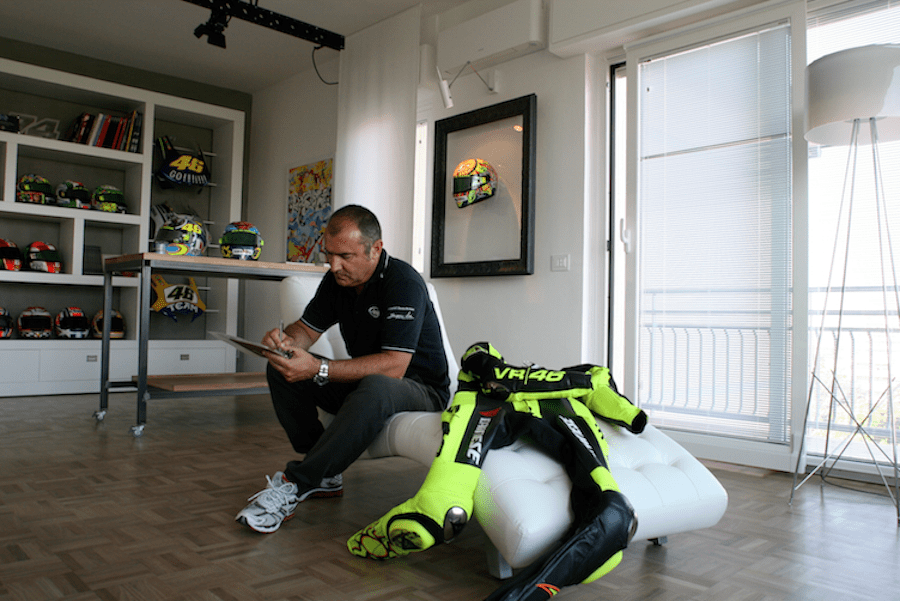

Despite not many people knowing what he actually looks like, Drudi is one of motorcycle racing’s most recognisable names off the track.

Born in 1958, Drudi worked alongside many top motorcycle racers, though the one he’s most famous for and instantly associated with is nine-time world champion Valentino Rossi. In fact, the Italian superstar has never worn a helmet not designed by the 60-year-old artist.

The impact of his works is so great that Italy’s largest science and technology museum, the National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci in Milan, recently hosted an exhibition of Valentino’s Drudi-designed helmets, motorcycles, leather suits and concepts, to celebrate what is considered not just significant in grand prix racing circles, but which represents modern cultural significance to Italy itself.

Speaking with Drudi at this event gave me the opportunity to dig deeper into the heart of a creative process that involves possibly the greatest motorcycle racer of all time, and understand a little more about the relationship that could be considered one of the most vivid between a sportsman and an artist.

We talked in his studio in Riccione, with a wide window from which you overlook the Adriatic Coast and beachgoers, not to mention commuters and trains, and which is less than 10km from the Misano World Circuit Marco Simoncelli.

Your relationship with Valentino grew from your friendship with his father, Graziano, a former racer who in 1979 won three 250cc Grands Prix. How did it start?

My brother was the owner of a dance club called Scorpio in the city of Urbino, and in the mid-1970s Graziano came there in order to court Stefania, who later became Valentino’s mother. My brother was one of the first of Graziano’s sponsors. He gave him something like 50,000 lira ($41 in 2018) for each race, which was not much really. I’m the one who cut from the leather the letters of the words ‘Scorpio Club’ that were sewed onto his suit.

Were you attracted by motorcycles at the time?

Of course I was; it was very common in this part of Italy. Graziano and I had fun on the beach here on the Adriatic Riviera, riding a Honda XL, mounting a slick tyre on the rear. In the morning, the low tide left a portion of sand that was so smooth it was perfect for sliding.

You know the days Valentino trains at the ranch – his facility in Tavullia where he can do flat track – well, what we did back then on the beach was the first chapter of the story that led to the ranch.

So you became tight friends?

Like brothers. Valentino and I are also the same, because I suffer of the Peter Pan syndrome, which means that I think I’m young and I’ll be so forever. Due to my job, I work with very young people, since riders in the Moto3 class are often less than 18. This keeps me fresh.

From your point of view, what is Valentino’s best quality?

He recognises the importance of listening to others and respects their skills. He has always been a great listener; when he was a kid he was so curious, always asking questions. I remember he was with us when we gathered for the winter holidays in Livigno, in the Italian mountains, with some riders of the time like Kevin Schwantz. Little Valentino was so excited and eager to listen to stories and learn new things. He was the first to wake up and the last to go to bed.

Did he ride at the time?

I remember an event in which I somersaulted one of Graziano’s cars while I was participating at a drifting race. I was afraid he was going to get mad, instead he said, ‘Great, this is the right way to end the day!’ It was the mid-1980s, so Valentino was probably six or seven years old. There he was, driving a small go-kart in between our races. He was drifting all the time.

What is an adjective which fairly describes Valentino?

Colourful. That means that he recognises the importance of fantasy in life. He’s in some way free, he feels free to have his own vision of the world, and this makes one unpredictable and not controllable.

You two know each other really well. How has he changed through the years as a rider?

He became more and more professional. I can see that in the way he now sets up his Yamaha YZR-M1. Other riders, once they reach a certain level during the practices, say, ‘Okay, that’s it, now I’ll focus only on trying to be as fast as possible.’ Instead, Valentino continues to search for perfection. He prefers to start from back on the grid but to spend 10 or 15 more minutes working on the bike. That’s why sometimes he finds the ideal setting only during Sunday’s warm-up.

Was the iconic sun-and-moon helmet your first contribution to Valentino?

No, it was the choice to use the colour yellow. It happened when he raced in the 125 European Championship in 1995. I worked for Kevin Schwantz, who retired when Valentino started to get serious about racing. So I told him, ‘The yellow colour will pass from Kevin to you.’ Valentino was ecstatic about it.

How did the sun-and-moon idea come up?

We had a common friend whose nickname was Jumbo, a guy who used to work in disco clubs. I had made a drawing about his face being the moon. It was a gift for him, a birthday present. Valentino came with me the day of the party, he saw it and liked it so much that he asked me to

have it on his helmet. He had already developed the idea of the sun, then he decided to have two different sides, night and day. So the moon is Jumbo’s face. I want to point out that the night does not represent the dark side of Valentino, it’s not a matter of opposite things, like black and white, good and bad. It’s the action of the day and the meditation of the night. Also the fact that Valentino is a night person plays a part in it. He loves to hang out until late.

Of all of his helmets, which is your favourite?

I don’t have a favourite helmet. It’s complicated to tell. There’s one that gave me very special feelings, though. It’s the one he used in Misano in 2014, with the handprints of the people close to him in life, including his mechanics and his mother, Stefania. I like to think that it gave him a special energy, a sort of pranotherapy that kept him focused. It worked, because he won the GP.

Why is Valentino, like many other riders, so superstitious of his helmet, and puts so much importance around it?

Here we’re talking about the story of mankind, not the story of a rider. From a far era, people who deal with danger paint their head and face. I’m thinking about Indian Americans and medieval knights. It’s an ancient story, a way to keep away the fear. And also to try to look aggressive in front of your opponents. Speaking of Valentino, you should consider that he’s also a great fan of racing helmets, both in F1 and motorcycle racing. He has a huge culture about them.

What’s been your worst experience with him?

In 2004 he asked me for a helmet with a wooden effect that had to symbolise the fact that he was fourth in a lot of races. You know, gold is the first, silver the second, bronze the third

and wood the fourth. I didn’t like the idea too much, so I showed him a first prototype that was orange instead of brown. He told me, ‘I don’t like it, I will not wear it.’ I was shocked, it was the first time he told me something like that. On the spot, I saw it as a lack of respect. But then I stared at the helmet and admitted it was awful, real shit. So I stuck to his idea. He wanted it brown, wood effect. Generally no helmet is done just because it looks nice. They all have a particular meaning, a message, a concept behind them.

I don’t see a computer in your office – that’s weird.

I don’t use one. I don’t like those sorts of devices. I draw by hand. For me the process needs to be natural, to fully and exclusively involve my mind, with no kind of external help. Something pure.

What is your direction now as an artist?

The trend is to try to be more simple, to reach the essence. In the past I made very complicated stuff, but not now. In 2017, for example, with Valentino we made a helmet that showed specific symbols: circles, triangles and squares. Those are geometric figures linked to the theories of Leonardo Da Vinci and Fibonacci. There’s an esoteric background, the three figures symbolise the search for perfection, which is a sort of motivation that Valentino and I, in our fields, surely have.

One day you’ll probably have to quit designing Valentino’s helmets. How will you feel?

When he quits with motorcycles, he’ll continue with rallies, and then who knows what. He’ll race something for his whole life and he’ll always wear a helmet. So that moment will never come for me.

Words Jeffrey Zani

Photography The National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci