When the invitation first came through to ride a Royal Enfield Himalayan in the Himalayas, it included an ominous warning: “The ride will start from Leh, which is at 3500m/11,000ft above sea level and will go up to 5350m/18,300ft!”

High altitudes can induce mild symptoms like a shortness of breath and dizziness, which are hardly conducive to riding a motorcycle, while more severe symptoms can leave a person completely incapacitated. I’ve suffered mild altitude sickness before, at only 4800m, so if I was going to ‘Moto Himalaya 2022’ in three-months’ time, I would first have to get into shape… and research what pills to pop to minimise the chance of getting crook.

Royal Enfield advised that a suitable fitness level for the trip would be being able to “complete 50 push-ups and 5km of running (muscle power and endurance) in under one hour”. Five kilometres? No worries. 50 push-ups? Dreamin’. Nevertheless, I got to work and could do 30 of the terrible things before a bout of Covid ended my training regime. I declared myself fit.

The lead up to the Himalayan adventure was packed with filling out medical and indemnity forms, insurance policies, visa applications and generally more paperwork than you can poke a Derwent HB at. I was one of four Aussie motorcycle journos slated for the trip, and we’d be joining a bunch of riders from Indonesia. One of the Aussies was a late scratching, meaning there would be a spare bike in the back-up van, aka the Gun Wagon.

After three years without international travel, I was a bit rusty with the paperwork when I got off the train at Sydney airport; I wasn’t even allowed to join the Air India check-in queue until I’d fumbled around for a pen to fill in an obscure form requiring the name of a contact person at my destination and details of the accommodation booked. This was to be the first of many bureaucratic hoops over the next two weeks.

The flight from Sydney to our overnight stay at New Delhi took around 12 hours, before a 90-minute flight to Leh the following morning. The airport terminal at Leh is tiny (a new one is under construction) and chaotic, and we weren’t allowed to exit until we’d been subjected to a PCR test, despite having Covid-vaccination certificates. Once out the door, we met the jovial and excited Indonesians who would be riding with us, as well as our tour leader Aakash and tail-end Charlie Jitin. We were ferried off to the Hotel Lakrook and instructed to avoid alcohol and to take it easy for the rest of the day to acclimatise to the altitude.

We had a bit of time for a wander around Leh, which is a centuries-old city of around 30,000 people surrounded by the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas. In years gone by it was an important stopover for traders travelling between India, Tibet, Kashmir and China, their wares including grain, silk, cannabis resin and cashmere wool. These days the streets are lined with small shops – selling nick-nacks and Pashmina (cashmere) shawls, scarves and wraps – alongside restaurants, hotels and countless motorcycle-hire outlets.

Riding bikes through the Himalayas is big business.

That afternoon we got together and met the rest of the Moto Himalaya 2022 team, which included an orthopaedic surgeon (Dr Tsering Wangchuk), a specialist Royal Enfield mechanic (Rahine), the content crew (photographers and videographers), and the blokes who would drive the luggage truck and pre-run the route with our paperwork to expediate passage through the many checkpoints along the way. Moto Himalaya has been conducting tours here for years and has the process down pat, so riders have nothing to worry about but the terrain and the traffic.

To familiarise us with that terrain and traffic, our first ride the next day would be a short 60km round trip from our hotel to a small café at the confluence of the Zanskar and Indus Rivers, which is a popular spot for rafting tours. This offered a glimpse of what lay ahead; the way the traffic flows, the overtaking procedures, and riding through the plumes of black smoke emitted by the many civilian and army trucks – no Euro 5 here! One truck driver we encountered on the way back to the hotel must’ve been as high as a kite; he nearly took out an oncoming army truck on a blind corner, and then almost wiped out a procession of cars when he tried to pass them on the inside, straddling the gravel verge and forcing them out of his way as he re-joined to the blacktop. No Fs given.

Safely back at the hotel that afternoon, we parked the bikes, jumped in a taxi and headed up to the Ladakh Shanti Stupa, an impressive Buddhist temple that overlooks Leh. From here we could see the road that would tomorrow take us up to the mighty Khardung-La (‘la’ means pass), which was once declared the world’s highest motorable pass at a staggering 17,582ft (5359m). It’s now recognised as the 11th highest.

A good night’s sleep would’ve been appreciated but the infamous dogs of Leh put paid to that idea; the little buggers sleep all day and bark all night. Nevertheless, we were up early to throw larger bags in the luggage truck and load up our Himalayans with gear we’d need for the ride. I also sorted out some GoPro mounting positions and fitted my Quad Lock phone mount, and then I tied some Tibetan prayer flags between the mirror stems to “appease the mountain gods”. I’m not a religious bloke but hey, when in Leh…

Our destination was a camp in the Nubra Valley, some 128km away, but before reaching there we would have to conquer Khardung-La. We weren’t far out of Leh when I was almost taken out by a colourfully painted water truck heading the opposite way; it was an early reminder to stay on my game, and to expect the unexpected on every blind corner, of which there would be literally hundreds ahead of me over the next several days. I pulled up after about 30 minutes or so to take in the breathtaking scenery and to grab a few happy snaps. The scale of the mountains here really is incredible.

As well as the thinning atmosphere, the traffic seemed to thin out as I neared the highest point of Khardung-La, and despite the ever-decreasing performance of my Himalayan, which was now gasping for air just as I was, it still built up enough speed that I thoroughly enjoyed every twist and turn up that imposing mountain road.

After taking the obligatory tourist shots next to the ‘Mighty Khardungla’ sign, travelling buddy Stuart Woodbury talked me into clambering up a flight of stairs to check out an alternate view through hundreds of Tibetan prayer flags. While the outlook was enough to figuratively take one’s breath away, it was the climb up the stairs that did so literally. After 15 minutes or so we decided it was time to begin the descent into the Nubra Valley.

The run down the hill was our first chance to really stretch the legs of our Himalayans, and with no posted speed limits, we gave the little Royal Enfields the berries, occasionally reaching an indicated 120 clicks! One of the Indonesian blokes, Ricky, was keen to go with us, and he was constantly weaving from side to side, looking for any overtaking opportunity so he could slot in behind our lead rider. Was it a race? No. Did we get a bit carried away? Maybe.

The road surface was pretty good for much of the ride but you never knew what to expect. There were a few sections where the bitumen suddenly gave way to gravel on the tighter switchbacks, there was always the possibility of rocks being strewn across the corner exits, and there was even a small oil spill that caught us off guard; luckily no one binned it.

We pulled up at a river crossing where Stu filled his bottle with water straight off a glacier, and then pressed on to our lunch stop at imaginatively named The Mid-Way Restaurant where we woofed down plates of salty fried-egg rice and cups of sickly sweet, sugar-laden coffee. Ordering food and drinks here was going to take some practice.

It was mid-afternoon when we arrived at our digs at Nubra, which consisted of a semi-permanent tent with a double bed and an ensuite – talk about roughing it! I went in search of a Dan Murphy’s with my other Aussie travelling companion, Nigel Peterson – after all, we’d been off the cans for three days now! We eventually found a small bottlo and grabbed a six-pack of beers and a cheap bottle of whisky for Stu, and then enjoyed a quiet drink overlooking the resort’s garden of pretty wildflowers, vegetables and herbs. At high altitude, even the most seasoned drinker can become cheap drunk, so we took it easy and, after a tasty vegie-curry, everyone turned in for an early night.

The next morning we were stands-up and out of Nubra bang on 8.30am for the 169km ride to Pangong Tso (Pangong means high grassland and tso means lake). The ride started off on sealed roads, but we were soon on gravel, with a few rocky sections and sandy stretches thrown in for good measure. It was difficult to concentrate on the road at times due to the stunning scenery; huge mountains on either side, the picturesque Nubra River and the threatening scree fields, the latter occasionally inhabited by small groups of workers moving rocks around by hand.

When we stopped for lunch, it became apparent that a few of our new Indonesian mates were suffering from altitude sickness, and one fellow took the opportunity for a lie-down in the middle of the small restaurant. I had started taking Diamox two days before landing in Leh to help with acclimatisation, and I recommend it to anyone travelling to the Himalayas.

We pressed on along more dirt roads and eventually found ourselves riding through a dry, sand-filled creekbed before we busted out on to a sealed section with some nice flowing corners, and then we were back on the dirt again and nearing the bright blue Pangong Tso. The bracken lake is truly iridescent in the sunlight, which is in stark contrast to the grey and brown hues of its mountainous surroundings. Part of Pangong Tso is in India, part of it is in Tibetan China and a small section is in a disputed area, which the Indian and Chinese armies have recently had deadly skirmishes over. We were about 60km from the disputed area.

The content crew enlisted Stu and I to go and get some action shots on our Himalayans down by the lake, which included a small jump-up and a sandy track that was a soft in sections as deep bulldust. Normally it would be an easy ride but at 4225m (13,862 ft) it was hard work.

The accommodation consisted comfortable cabins overlooking the lake and I got a decent night’s sleep despite the barking dogs and the altitude. Four of the Indonesians, on the other hand, did not; Doc Wangchuck set up an infirmary in one cabin and several oxygen cylinders were emptied that night. Nevertheless, their spirits were high in the morning and they seemed ready to roll after brekky.

Our route had us backtrack for a distance along the dirt and sealed roads, back into the sandy creekbed and on to Tangtse check post. I was riding in a small lead group with Aakash, Stu and Nigel, and we had a brisk and fun ride to Tangtse, where we awaited the rest of the convoy. We soon got word that one of our crew had crashed heavily in the sand, and the Doc had taken him to have his leg X-rayed, while his bike was loaded into the Gun Wagon. There was a break, and Doc Wangchuck soon had the rider’s leg in plaster for the drive back to Leh.

Before Leh, however, we would have to conquer Chang-La, which at 5391m (17,688ft) is actually higher than Khardung-La, and the 10th highest pass in the world. It is in fact higher than the Everest basecamps. The road up to Chang-La is a mixture of sealed and unsealed sections, with pavers near the top that are apparently less prone to damage from the extreme weather conditions than bitumen. There were plenty of tricky roadworks and heavy machinery to negotiate, and the route was quite rough in sections; it would’ve been hard on our fallen colleague, bouncing around in the back of the Doc’s Toyota Fortuner with a busted leg.

We stopped briefly atop Chang-La for photos and then had a fantastic (relatively) high-speed run down the other side; bloody good fun. Next was a lunch stop at a roadside restaurant where we were joined by an amusing roadworker who was off his chops. These blokes work bloody hard breaking rocks with sledgehammers in some of the world’s harshest conditions, so you can hardly blame this one for having a few bevvies on his day off.

The run back into Leh was through heavy and occasionally unpredictable traffic, and although we had only covered around 140km by the time we arrived back at the Hotel Lakrook, it felt like a much longer ride than that. After a wander around the Leh markets, we found a rooftop restaurant that afternoon that did a killer Tandoori chicken, served with a cold-ish beer.

The howling canines of Leh were at it again that night, and after I drifted off, I was first woken by the late-night musical garbage truck (the music alerts people to its presence so they can empty their bins into it) and then again by the Muslim call to prayer at 4.27am, giving me plenty of time before sun up to pack my gear for the next three days of riding.

That morning, after farewelling our fallen Indonesian mate (he was flown back home to Jakarta), we saddled up for what would be a long 220km ride to Tso Moriri (Mountain Lake). There would be a fair chunk of off-road riding to get there, with Aakash explaining that the Moto Himalaya route intentionally becomes more challenging day by day. It turned out to be an epic ride across sealed sections, some broken asphalt and rough dirt roads with mix of gravel and sandy bases.

After working our way past several convoys of army trucks, we had a picnic lunch in the shade of small trees beside a freshwater creek. The geography here was once again mesmerising, and our route took us through a deep valley alongside a raging river, across a small water crossing with a rocky base, and then into open grassland with a series of parallel tracks that disappeared over the horizon. This was my fifth day on my little RE Himalayan, and I was really starting to gel with the bike, despite it obviously having had a hard life… and a worn shock.

As we approached Tso Moriri, the open grasslands gave way to a narrow dirt road with massive washouts and an imposing and occasionally overhanging cliff face on one side. There were also some soft sandy sections and the content crew managed to get their car stuck in one of them. We eventually arrived at our accommodation overlooking the lake, which once again consisted semi-permanent tents. As with many of the previous stopovers, electricity and running water was only available for a few hours a day, so charging camera and phone batteries was always a bit of a challenge, the power here supplied by the nearby army base.

Tso Moriri was our highest camp to date at 4522m (14,836ft) and some of the blokes were really struggling to cope in the thin air – the fact a few of them were on the bungers probably didn’t help their cause. The Doc had loaded up with more oxygen cylinders in Leh, but he was concerned at the amount the affected Indonesians were going through, and he kept pleading with them not to smoke.

The next day we only had 110km to cover, so we had a relatively leisurely 9.30am start, but most of the route would be on dirt roads to Tso Kar. After messing around to get some photos, we had an early lunch stop at another roadside restaurant that, despite its rudimentary looking facilities, served excellent fried rice and dahl.

Tso Kar is a small yet picturesque saltwater lake situated at a lofty 4530m (14,860ft) and surrounded by snow-capped mountains. There is a variety of birdlife here which we saw when we wandered down to the water’s edge for an afternoon beverage. This was followed by an impromptu game of cricket on the main road that was occasionally interrupted by passing cars and trucks.

The rooms at the Tso Kar Eco Resort were pretty crook, and I reckon the cleaner must’ve been laid off at the start of Covid and never re-employed, but we would be riding back to Leh the following day for the final time, so no point complaining, eh?

Once again, the altitude was wreaking havoc on a few of our colleagues, so Dr Wangchuck whipped out the Portable Altitude Chamber (PAC) and gave us a demo. He placed patients inside one at a time, zipped it up and started on the foot pump, gradually building up the air pressure to the equivalent of sea level. It only took a few minutes for the blood oxygen level in each patient to quickly rise. It’s reassuring to know you have first-class medical back-up when you’re riding in such harsh and remote terrain.

I woke up feeling tired and hung-over the next morning despite not having a drop to drink the night prior. I made sure my hydration pack was topped up before I got back on my bike, with one more mighty pass to conquer between us and our return to Leh.

Taglang-La is a whopping 5328m (17,480ft) high, so is only slightly lower than Khardung-La and Chang-La, and is the world’s 12th highest motorable road. The ride started off on dirt and broken bitumen, and then as we approached Taglang-La the surface transformed into recently sealed bitumen. Stu and I pulled over enroute to the top for a glove change as the temperature started to drop, and then we pressed on up the steep mountain climb, with throttles wound back to the stops, cranking into corners so as not to lose any hard-won momentum. It was another fabulous ride in a truly spectacular part of the world that I feel privileged to have visited.

Again, we stopped at the top for photos then had a great run down the other side of the pass. Nigel managed to pick up a puncture just a few kilometres short of Leh, which Rahine swapped over in no time thanks to a spare wheel he was carrying in the Gun Wagon. Out of 19 bikes, there were only two punctures on the entire trip, and we rode over some extremely rough terrain.

That night, back at the Hotel Lakrook, the Moto Himalaya crew entertained us with a slideshow of our adventure, and awarded us with certificates for completing the eight-day ride. A few of the boys cracked on until the early hours and there were plenty of empties scattered around the hotel’s restaurant the next morning.

We still had a flight to Delhi and then a couple of flights back to Australia ahead of us, along with all the paperwork and security screening that would entail, but as we bundled into a taxi for Leh airport our Moto Himalaya adventure was officially over. It had literally been the trip of a lifetime, and I strongly advise anyone who gets the opportunity to ride in this amazing part of the world to grab it with both hands.

The Bike

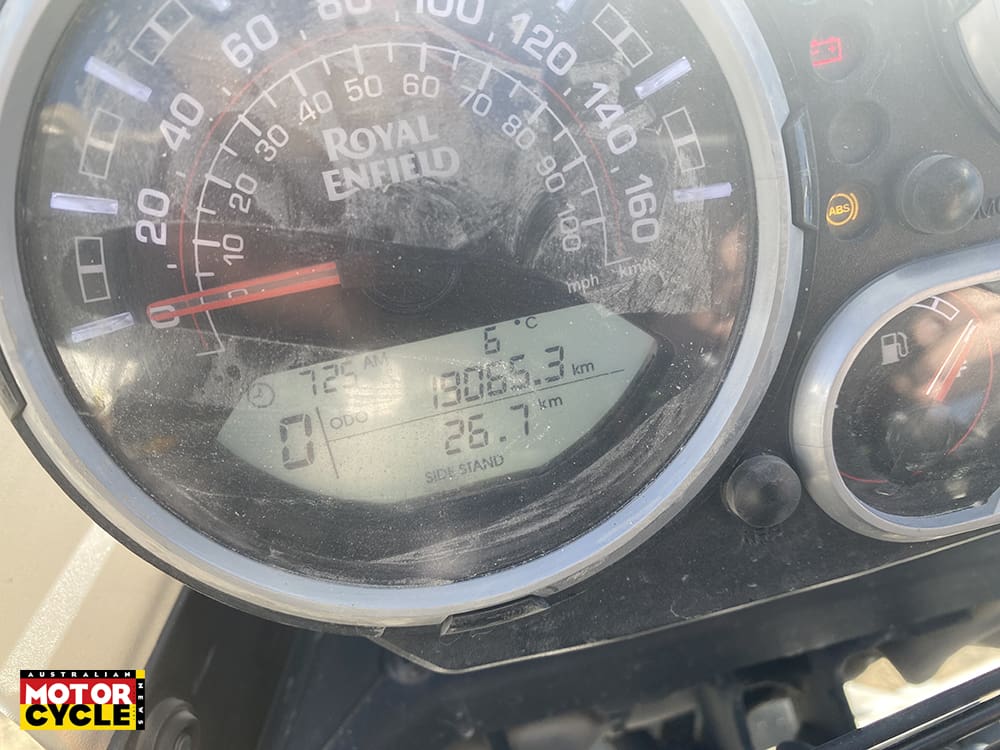

Although Moto Himalaya is an official arm of Royal Enfield, all tour companies must run hire bikes in the Himalayas due to union rules. My RE Himalayan had 18,500km showing on the odo at the start of the trip and looked like it had had a hard life. Despite the noisy clutch when cold and the worn shock, it was the ideal bike to ride in the Himalayas.

Of course, a bit more power would have been nice, but you really wouldn’t want anything too powerful (or heavy) in this environment, or you’d soon get yourself into strife. Oh, and that massive looking chain guard? Apparently it’s so the pillions who ride side-saddle don’t get their frocks caught in the chain.

The Roads

Most of the roads in this region were constructed by and are maintained by the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) to support the Indian Armed Forces who secure the country’s borders. There are a lot of military bases in the Ladakh region, and it’s always advisable to give way to army convoys, not just because they are in big trucks, but because you are riding on their roads.

The Gear

There are temperature extremes in this part of the world, from +40°C-plus in summer to -30°C in winter. We were fortunate on our trip to have relatively mild conditions, but it pays to be prepared.

I ran an Rjays Adventure suit, Argon Turmoil gloves, spare Rjays winter gloves, Sidi Adventure 2 boots and a Zerofit Heatrub Move thermal layer. I wore an Arai XD-4 adventure helmet. As well as camera gear, we had to carry a spare set of clothes on the bike in case the luggage truck went AWOL, so I fitted an old Oxford tailbag to my Himalayan. I also carried Imodium and dunny paper with me everywhere (as advised by Youngy), and as well as running a three-litre hydration pack, I took Hydralite daily to prevent dehydration.

Who and how much?

Moto Himalaya 2022 cost $US2000 ($AUD3100), which includes bike hire, fuel, medical and mechanical support, all accommodation and most breakfasts and dinners. You’ll occasionally have to fork out for lunch, but meals are incredibly cheap. This is one of the best planned and well organised tagalong tours I’ve ever been on.

Return flights to New Delhi on Air India cost around $1700. Return flights from New Delhi to Leh on Indigo are around $150, but factor in an extra $80 each way for extra luggage.

Contact: Moto Himalaya – royalenfield.com

WORDS // DEAN MELLOR

PHOTOGRAPHY // MOTO HIMALAYA & DEAN MELLOR