Less than 50 miles after setting out on the first landwards leg of his odyssey, 26-year-old Doug Voss faced his moment of truth. There was no spectral light, just an ominous gritty sound as the cush drive on his Royal Enfield filled with sand and locked solid. Then followed a resounding crack as the drive chain pulled the brake from the sprocket band. Doug was going nowhere.

From its inception, Doug’s plan to ride his 500cc Model J Royal Enfield to London had been beset by problems. Shortly before his departure in July 1952 he learnt that Iran had nullified British Petroleum’s oil ‘concession’, rendering anyone remotely related to the Commonwealth persona non grata. This forced Doug to ship his Enfield, now with a custom-built storage box on a Hawk sidecar chassis, to Basra at the head of the Persian Gulf. Here the British Consular Official strongly advised Doug to return to Bombay, deeming the outfit ‘undesertworthy’. This advice may well have been prescient as first the Enfield’s speedometer disintegrated, then both footrests snapped off; and now the unit had lost all drive. It was 50°C and the nearest town was aptly named Kut.

With the use of a hand-cranked grindstone and a flash course in arc welding, Doug soldiered on, but the abrasive sand that had ruined the cush drive had been ingested into the cylinder. “In Baghdad I found a workshop that was no more than a hole in the wall,” recalls Doug. “They made a sleeve and I used the old piston with a new set of rings I’d been carrying, so I was mobile again.”

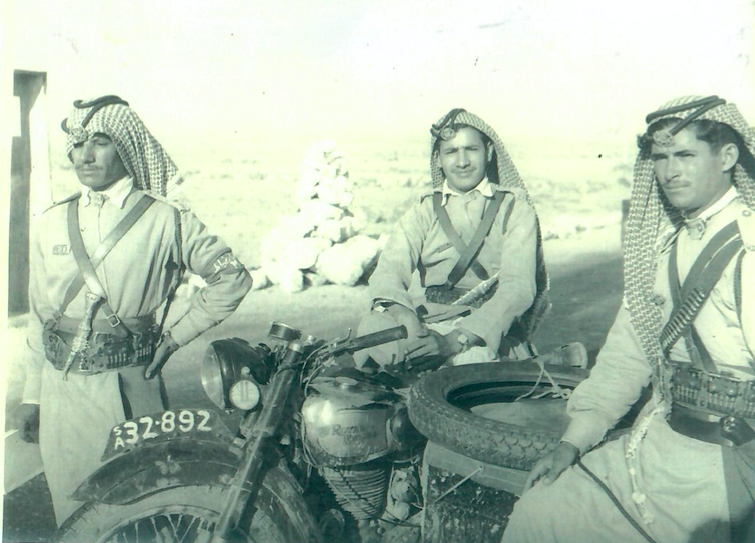

Before crossing the void that is the Syrian Desert, Doug was cautioned about the relentless sun and advised to travel after dark, by following one of the giant 10-wheeled Marmon-Herrington articulated buses heading to the fortress-like kasbah at Rutbah Well, the midpoint of the journey. Doug intended to do just that, however, the bus travelled at an average speed of 110km/h and, to avoid bandits, slowed for no one. “This speed was quite beyond my overloaded outfit,” said Doug, “and the road was a narrow, patchy bitumen track, which I often abandoned for the smooth desert.” The soldiers of the Arab Legion were pleased to see Doug arrive and invited him to stay in their post. The rest of the journey was uneventful, and despite some visa hassles with the Syrian authorities, Doug pressed on quickly through Turkey, Greece, then north into trouble-torn Yugoslavia.

Here Doug met a like-minded adventurer riding a 250 Puch two-banger. Rolf, an Austrian, knew the lay of the land and offered his services as a guide over the more passable mountainous roads to Italy. It was while chasing Rolf through one of the army checkpoints that Doug failed to stop, was rounded up, and thrown into the watchhouse. Hours of fruitless interrogation later Doug was ordered to leave Yugoslavia by the shortest possible route. “That was fine by me,” he recalls, “the Italian Motorcycle Grand Prix was on at Monza just across the border.” After his earlier experiences the ride to Calais was a doddle and the ferry across the channel most pleasant – particularly in comparison to the Bombay-based coastal trader on which Doug’s adventure had commenced.

Doug entertained plans to return to Australia via Africa but while in London he met his future wife. So the Enfield was shipped home to Adelaide where the box containing the twin 20-litre containers for fuel and water were removed and replaced with a Goulding sidecar. Doug still takes the outfit for the occasional ride and reminisces that “generally I received nothing but help and friendliness in the Middle East. Sadly those times have long passed.”

WORDS PETER WHITAKER