You can’t accuse Triumph Australia of not giving new bike models a thorough test. In fact, through its local product launches the company has earnt a reputation for giving both bikes and journos a warts-and-all challenge, with neither guaranteed of making it back in one piece.

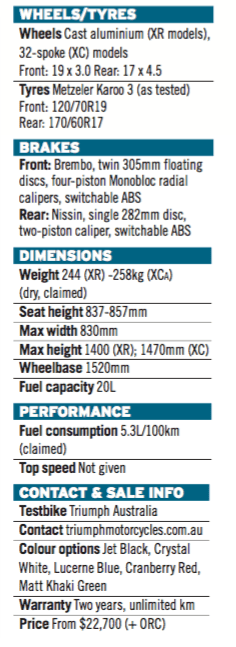

The Aussie launch of the new Tiger Explorer 1200 range was no different. This time we were treated to a three-day off-road adventure on Cape York Peninsular using the most outback appropriate models in the range: the spoke-wheeled XCX and XCA. The three-tiered road-biased XR Tiger Explorers – distinguished by their 17-inch cast wheels front and rear – have received much the same comprehensive suite of updates as their burlier brethren, but this trek required the most rugged rigs available.

The original Explorer 1200 was developed first and foremost as a roadbike. Although it looks born for off-road adventure, the base design has always been that of a tarmac focused soft-roader. No wonder it makes for an outstanding long-haul black-top tourer. But the burgeoning British marque has been working long and hard ever since the model’s 2013 release to adapt it for more serious off-road use – to make it a bike worthy of taking on the big hitters in the heavyweight adventure bike market, and a genuine all-roads Explorer. With this latest version of the Tiger Explorer XC, Triumph has finally done it.

The difficulties in this quest have been manifold. The biggest challenges have stemmed from the Explorer’s road-focused chassis geometry, and the feisty influence of its three-cylinder powerplant. From a weight distribution perspective, Triumph also has the disadvantage of working with the top-heavy design of an in-line multi-cylinder engine. So although the overall weight is similar to its almost exclusively two-cylinder competition, its centre of mass is higher. This characteristic can be made to work in your favour at high speed on a roadbike, but for a heavyweight off-roader picking its way slowly through technical terrain, high is a much less virtuous place for gravity to … erm, gravitate.

The latest generation 1215cc triple-cylinder engine makes the Explorer the most powerful shaft-driven bike in its class, topped only by KTM’s chain-driven V-twins. But harnessing that energy in a form appropriate for off-road riding has added challenges to those inherent in the bike’s architecture.

Triumph’s response has been to take a holistic approach. The engine output is tempered via the ignition and ride-by-wire mapping. It’s also mediated by more sophisticated traction control and ABS systems, then transferred to the rear wheel via a smooth and snatch-free shaft drive. And finally, the grunt is put to ground more effectively thanks to the new TSAS equipped semi-active WP suspension.

Aussie torture test

If there was one constant in our three-day six-bike convoy, it was dust – cubic tonnes of it. The ochre red bulldust of the outback is an insidious and gaseous substance, seemingly thinner than the very air it uses to infiltrate orifices you never even knew you had. It’s so fine that it finds its way to the very depth of your pores, from where your body strains to reject the ethereal red wretch, staining towels and collars for several days. This stuff will also kill a bike in a trice – far more rapidly than doing donuts all day on the beach. At least with sand and sea salt you can see the damage being caused as the bike’s outer surfaces slowly fur up, then corrode. Bulldust gets into the workings of everything and acts like grinding paste to destroy a bike from the inside, without warning. The first signs of its evil deeds are usually sticky switches. But by the time you notice it, far worse crimes of friction will be taking place in areas unseen. With a shaft final drive and the air intake tucked away high under the tank, the Explorer is as well-prepared for the dust as it can be. The fact that all six bikes made it through three days immersed in the stuff without a hiccup is promising for anyone thinking of taking one of these machines for extended extreme adventures.

There were times riding the Explorer when I had to come to a halt as quickly as possible because I had absolutely no idea where I was heading. That’s the other thing with the talc-like bulldust – it tends to explode when slammed into by 350kg worth of bike and rider, causing a total blackout for anyone in hot pursuit. The tricky thing about taking this sort of evasive action is that the best way to ride the powder is to lean back and keep the throttle open, so trying to slow down in a hurry is a dodgy affair, even when you can see where you’re going.

Many times I trowelled the bike’s front end into the loose stuff aggressively, in a way that would have seen me exiting through the front door on the old Explorer quicker than you can say “pass the EPIRB”. But whenever the front wheel folded or washed out on this ride, I managed to dodge the dick of disaster and ride away with bike and body intact.

Of course it’s wonderful that the Explorer, like its direct competitors, is adorned with all manner of electronic trickery and widgetisation to make it more comfortable and user-adaptable. But my simplification of big-arsed adventure bikes is that only three things really truly matter: durability, power delivery, and suspension performance.

The need for durability is obvious, and must take into account the tiny minority of riders with the skills and strength to give one of these battleships a real off-road beating. The main guy charged with the task of dishing out cruel and unusual punishment to the Explorer on behalf of Triumph R&D is a very good friend of mine.

He’s an infinitely loveable bloke, but he’s also a complete animal who derives extreme joy from breaking things, and is very good at it. This comes as no surprise, as he’s a former British junior motocross champion who, at the thick end of his forties, still has the temperament of his MX youth but now weighs close to 100kg dripping sweat (which happens a lot). I have witnessed ‘Super Onz’ jumping early versions of the Explorer at heights and distances that would make a meeker man’s nose bleed. And all in the name of durability testing. No wonder none of us could break our bike then.

Power delivery is obviously critical for the low-grip high-momentum application such as this. With the Explorer it was important for Triumph to retain the sensory steroidal rush of in-line multi-cylinder muscle, to preserve the point of difference between this British taste of adventure and the various twin-cylinder configurations. The problem here is that multi-cylinder engines don’t naturally deliver the kind of power suited to off-roading.

But ride-by-wire throttle in conjunction with strategic mapping of the engine’s ignition timing can effectively give you two or more engines in one. The Explorer offers multi-cylinder-mental on the tarmac, then mild and measured twin-like power in the mud and grud.

Suspension performance is the third part of the big adventure bike trinity. Issues in basic chassis geometry and weight distribution can be lessened, if not cured, by intelligent and sophisticated suspension design; it’s far less likely for poor and unsuitable suspension to be cured by better chassis geometry. Big capacity adventure bikes are the perfect example of this general rule of motorcycle design, because they are intrinsically unsuitable for their intended task – they are too physically large, too heavy, and too powerful for any right-minded motorcyclist to ever want to ride off road. The Explorer takes these off-road compromises a step further, with a high centre of gravity afforded by its relatively tall inline three-cylinder engine, and front-end geometry which is at the road-going end of the spectrum, and even sharper than most MotoGP bikes.

That’s why it has taken some serious suspension development time to turn the 2016 Explorer XC series into the heavyweight adventure contender it is. Carrying on the collaboration with WP suspension – somewhat ironically owned by adventure bike rivals KTM – which has proved so successful on the Tiger 800 XC, the Explorer also employs the TSAS semi-active suspension system jointly developed with WP.

The performance of this suspension is so superior to the previous Explorer as to render it almost incomparable, particularly off road. The contrast to the 2015 model is proof positive of just what a good set of suspenders can do for what was once an adventure bike wannabe.

Like all the current crop of tech-heavy off-roaders, there is a trick to navigating the rider-mode menu and arriving at the best combination of suspension and engine characteristics for you and the terrain you’re on. Don’t get trapped into thinking the most appropriate option is the rider mode with the name most similar to the conditions you are riding – Rain for rain, Road for road, etc. These are a good default, and a guide for where to start, but if it doesn’t feel like it’s working try something else to reference against, always using common sense as your guide.

The Explorer’s Off Road mode defaults to a level of traction control, which will certainly keep you out of trouble on gravel and dirt, but show it a slimy river crossing or an extremely steep and loose climb and it can rob you of all necessary momentum. In these situations, it’s best to disable the traction control and practise your old-fashioned throttle control.

Switching to the Rain mode’s throttle map makes power delivery easier to control and helps maintain traction and momentum. The Touring mode’s suspension setting – at the softer ‘Comfort’ end of the scale – will help load the rear tyre to find grip. This combination of turning traction control off and selecting the Rain mode engine map ended up as my preferred off-road setting. I adjusted the suspension to suit the terrain and speed as we went along, using the full range of adjustment, from Sport mode firm for fast and rough riding, through to Touring mode soft for slow, loose and slippery.

One thing I never had any desire to change from the default settings was the ABS. Off-road mode disables the ABS at the back, allowing you to steer with the rear, and also recalibrates the front ABS for minimum intervention on ultra-loose surfaces. Even in motocross boots, the rear brake was progressive enough to give good feedback once I got the feel for it. But it’s a shame Triumph hasn’t fitted a brake pedal with adjustable height for sitting or standing. It’s crucial that your ankle isn’t strained at the bite point, so you can be light-footed and controlled when applying the rear brake.

The new-for 2016 brakes are a mighty set of binders. At the front, supersport-spec Brembo radial monobloc M4.32 calipers grip twin 305mm floating discs. And at the rear, a disc of almost planetary proportions, 282mm, is squeezed by a two-piston Nissin caliper.

Cornering ABS is now standard on all but the base model XR. This adjusts ABS intervention depending on lean angle, and while its performance is not the kind of thing that’s either easy or wise to test deliberately when 200km from civilisation, I can say I felt its benefits on more than one occasion, both on tarmac and gravel.

My one criticism of the Explorer’s chassis concerns something that only happened a couple of times over the 1000km of our predominantly rough off-road route, but is certainly worth noting. Twice I experienced sudden kickback through the ’bars when skimming over sharp corrugations at (very, very) high-speed. Neither time did I get particularly out of shape, but it alerted me to two things. First, it could have been nasty had I not been alert. And second, a steering damper would have rendered it a total non-event. Not having ridden the new Explorer with its original fitment Metzeler Tourance Next tyres, I can’t say whether the swap to same the company’s Karoo 3 knobbies has had an effect on high-speed stability.

However, given the bike’s remit, it should be equipped to perform equally well on popular brands of off-road-biased adventure tyres, and that would simply mean fitting a steering damper as standard. Several aftermarket options are available, and it’s the first upgrade I’d make given my love for taking the tough route. I’d even suggest getting your Triumph dealer to fit one pre-delivery, just to make sure there are no warranty issues.

Triumph has carried out a full revision of the cockpit, which includes changes to ergonomics, rider protection, controls, and instrumentation. The rider is now positioned 20mm further forward, which may sound like stuff-all, but it does help a short-arse like me feel more engaged with the steering and less extended at full lock.

Not being over-stretched when turning the ’bars sharply gives greater control for slow-speed technical riding, which is something our route had plenty of. I was most impressed with the Explorer’s new-found rider connection when standing on the ’pegs, which was necessary for long periods of time on this ride. The bike was fun and unfatiguing when standing, and I felt completely centred and in control in this position. That’s quite remarkable, because I’m the guy who usually stands up as little as possible off road.

If you think I must have spent all that time standing just to avoid sitting down, you’re wrong. The Explorer is one of the most comfortable motorcycles I’ve ever ridden in either position. My XCA had the gel seat, which I figured was named as such because it gelled with my arse like they were soul mates. It was love at first squish, and I’ve no doubt the happy couple could travel to the ends of the earth without a quarrel.

While the competitors are dreaming up new designs for manually adjustable screens, Triumph’s Explorer gets electric adjustment, and despite its mechanisms being showered in bulldust, the screen kept on working smoothly. The taller redesigned touring screen, fitted as standard on my XCA and also on the XRT, provides a haven of still and quiet air.

My only quibble is that, because the screen doesn’t have its own dedicated switch, you have to select Screen from the menu every time you want to adjust it with the main scroll switch located on the left switchblock. I guess that’s the price you pay for having so many gadgets – there’s only so much room on a handlebar to fit all the switches. In general, I found the menu selection process easy and intuitive, with everything becoming second nature in no time.

The cruise does have its own switch, and although it’s located in my least preferred location on the right handlebar, once set it’s an excellent system. For someone with child’s hands like me, holding a constant throttle while setting the cruise speed with your right thumb is an awkward task. Thankfully, once set, the Explorer’s cruise can be trimmed in 1km/h increments, will accurately track its set speed over undulating terrain, and also has a set speed display on the dash.

Another new addition to the Explorer’s flight deck is Hill Hold Control. A simple squeeze of the front brake when stationary and it’s activated. Pull away as normal and the park brake is smoothly released. It works a treat, and is a great feature for a bike built to be loaded up to its lugholes with luggage. The XCA and XRT come pre-fitted with pannier rails for Triumph’s own aluminium panniers, but you’ll need to fork out some extra biccies for the actual cases.

If the Explorer isn’t packed with enough gadgets, both variants are fitted with a single 5V USB and two 12V power sockets. Triumph must have great confidence in the Explorer’s charging system, because all but the base model also get heated grips, and both rider and pillion seat heaters are standard on the XRT and XCA, with the latter getting LED fog lamps as well.

2. Heated rider and passenger seats, not that Youngy needed them in Far North Queensland!

3. WP suspension previously appeared on the Tiger 800

4. Careful with that thumb Youngy – more features equals more controls

The auxiliary lamps may be meant for riding in foggy conditions, but they also provided a useful close-range addition to the Explorer’s excellent headlight. They were thoroughly tested during an unintended after-dark bulldust-cloaked scramble to find our Palmer River campsite on the second evening. There’s nothing quite like rough riding in the outback at night to test out a bike’s illumination capabilities as well as getting the adrenalin going.

I have to admit that when the invite for this launch first came, based on my experience with the previous model, I was more than a little concerned about the Explorer’s suitability for the intended route, and therefore its ability to guarantee my safety doing the sort of fast and slightly foolish riding I’d inevitably indulge in.

I got the last bit right, but my doubts about the bike were dispelled with the first dusty powder drift. Even if it did take a little piece of KTM suspension to get it right, like with the latest 800 XC, this Triumph Tiger is finally at home rolling in the dirt.

By Paul Young

Photography Danny Wilkinson