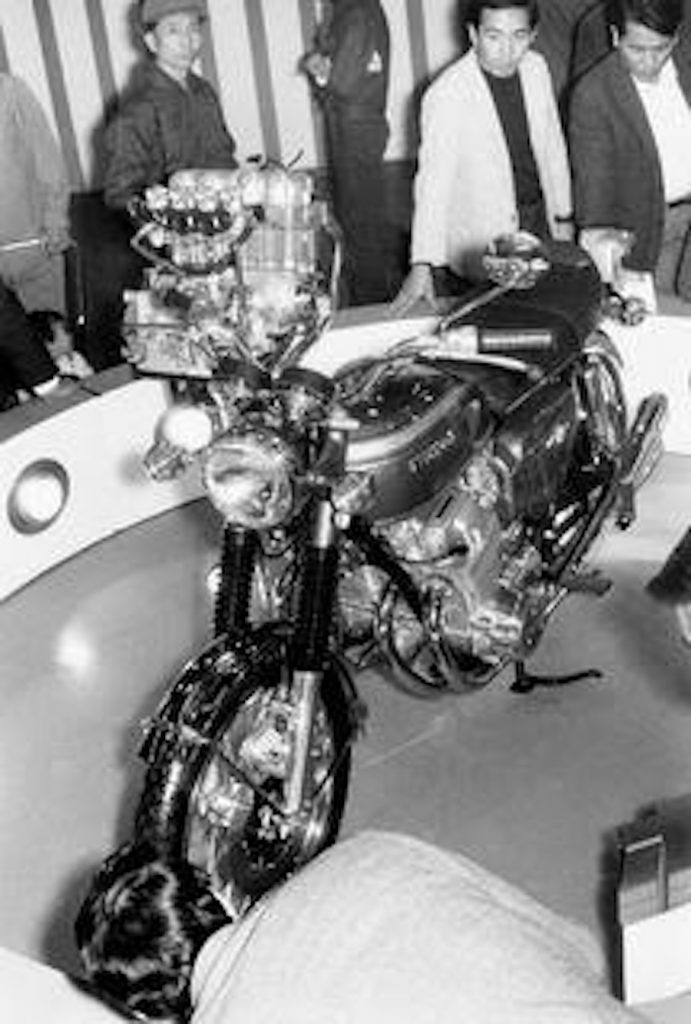

Kake rareta! Or, if you prefer the English translation, gobsmacked! That was the universal reaction as thousands of Japanese punters filed into the 1968 Tokyo Motorcycle Show, the centrepiece of which was the stunning new Honda CB750 rotating silently on a floodlit plinth, with an engine mounted on a stand beside it. The collective intake of breath was enough to suck the chrome off the petrol cap. Despite the intense scrutiny subjected to the Japanese factories as they cautiously entered the big bike arena, Honda had managed to create its stunner in almost total secrecy, and in just nine months from concept to metal.

In early 1968, Honda was busy getting the bugs out of its promising double overhead camshaft CB450 – the second model in the series that began two years earlier now receiving a much-needed five speed gearbox and other refinements. The engineer in charge of the CB450 development program, Yoshiro Harada, had visited America to stir up dealer interest in his twin, but encountered a certain amount of apathy from a market that still considered anything under 1200cc to be puny. The British manufacturers were experiencing the same message, and had already countered with the BSA and Triumph 750 triples.

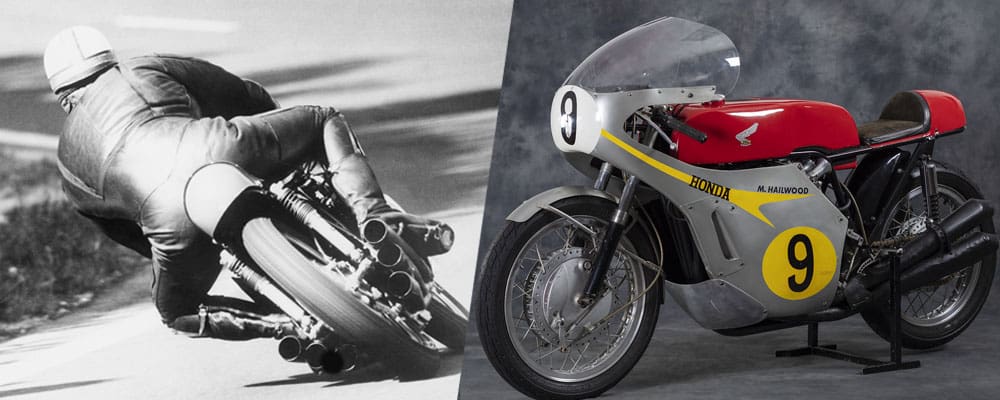

Soichiro Honda was not one to sit still for long. The decision to pull out of grand prix motorcycle racing at the end of 1967 certainly eased the company’s bottom line (further boosted by the end of their hugely expensive and largely unsuccessful Formula 1 campaign the following year), but it meant an uncharacteristic absence from the limelight.

By February 1968 he had appointed Mr Harada to head a team of around 20 engineers to come up with something big and fast. It’s believed that initially thoughts were given to doubling up an existing design such as the CB350 twin, or even the 450, but both were dismissed in favour of an all-new design. Within a few months, a prototype was circulating at the Awakawa test circuit outside Tokyo, appearing to be a CB450K1 rolling chassis (with a drum front brake) carrying a very compact looking four cylinder engine with four tapering black-painted megaphone silencers. Of course, Honda had vast experience with four cylinder engines, not just grand prix motorcycles but with the S500, S600 and S800 cars which first appeared in 1964. However these were DOHC water-cooled motors and were, quite correctly, deemed unsuitable for motorcycle use.

So as the doors flung open to the Tokyo show on 28 October, 1968, there in all its turquoise blue and gold 736cc glory sat what the world had been waiting for. True, it was not quite as it would enter production, but it was pretty close. The front drum brake on the test mule had given way to a single 296mm disc, with a caliper that had been arrived at following close inspection of a British Lockheed unit. It is also said that Mr Harada returned from America with a disc brake he had purchased at a ‘speed shop’, which was subsequently tested on a CB450. Regardless of its origins, the CB750 represented the first time a disc brake had been standard equipment on a mass-produced motorcycle. It ticked every box: four-cylinder SOHC engine, five-speed gearbox, electric starter, disc front brake – and a competitive price.

With the accolades from the show still ringing through the Tokyo streets, the rush was on to convert the display bike into production. The engines were built at Honda’s Saitama factory, while the chassis and other components came from the Hamamatsu plant. Output was way behind demand, primarily because the early engines used gravity die casting to produce the crankcases, which was a slow process and resulted in a roughish finish (these engines have come to be referred to as ‘sand cast’, which is not correct).

As soon as possible, after around 7500 units had been produced, this gave way to pressure die casting which was both quicker and cheaper, and gave a smoother finish. In 1971, production of all components was consolidated at the Suzuka plant.

Technically, the engine was a marvel of straightforward thinking and precision engineering. The crankshaft was a forged one-piece item with 36mm big-end diameters with slipper bearings, and five main bearings. Effectively two 180º twins, the outside cylinders reached top dead centre together and fired on alternate strokes, while the middle pair did likewise. Honda chose a slightly under-square layout (60mm x 63mm) to keep the engine as narrow as possible.

Few details leaked out to the west from the Tokyo show, so it was with high anticipation that the new CB750, now close to its final production form, appeared centre stage at the Brighton Motorcycle Show in UK in April, 1969. Nearly 50 years later, one of the two bikes displayed, in Candy Gold, would set a world record for the model when it sold at auction in UK in March this year for UK£161,000 ($277,000). This CB750 was one of four hand-built pre-production models which were shown around Europe and Britain for publicity purposes prior to their actual release.

Within a few months of going on sale, the CB750 (with race mods) had taken out the revival of the prestigious Bol d’Or at Montlhéry, France, in September 1969, ridden by Michel Rougerie and Daniel Urdich. Six months later, Dick Mann scored a fortunate victory in the Daytona 200 on a factory-built CR750 (the race version of the CB) – fortunate by the fact that the cam chain tensioner on Mann’s Honda (entered by American sponsor Bob Hansen, who was at the time American Honda’s national service manager), run separately from the three factory-entered bikes of Ralph Bryans, Tommy Robb and Bill Smith, began to fall apart halfway through the race. Mann’s machine was in the softest state of tune of the quartet, with the other three having more aggressive cam profiles, among other tricks.

The Hondas were, in fact, fortunate to be allowed to start, due to their illegal (in AMA regulations) magnesium crankcases. This was revealed during practice when Bryans crashed and his machine caught fire – the cases blazing away merrily. In return for Honda dropping a protest against the BSA/Triumph (non standard) five-speed gearboxes, the Brits agreed not to protest the Japanese bikes. All three works-entered Hondas, run by Honda’s Formula 1 team manager Yoshio Nakamura, retired with cam chain failures, while Mann scraped across the line just ahead of the fast-closing Gene Romero’s Triumph triple. Cam chain issues would become the model’s weakness that was never completely cured.

As the tumult from the CB750’s release in Europe and USA intensified, and Honda worked round the clock to up production to 2000 per week, Australian importers (in individual states prior to the formation of Honda Australia) waited impatiently for news of the local debut. That came in September 1969, but not as a shipload (or several shiploads) of bikes, but a single unit flown in to Melbourne on behalf of its owner, Bendigo motel owner Jack Walters.

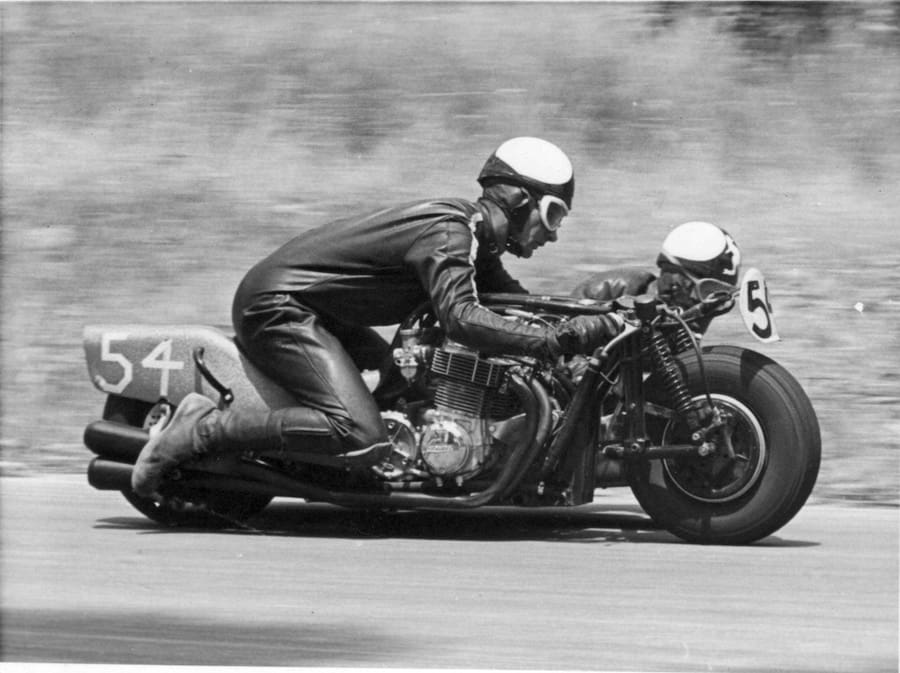

In an arrangement with Victorian importer Mayfair Motors, the Walters CB750 was displayed at the Melbourne Royal Show from 18-26 September, 1969, with a price tag of $1489, before Jack took delivery and handed it over to sidecar ace Lindsay Urquhart, who promptly whipped out the engine and installed it in one of his racing outfit frames.

However, prior to this apparently heinous act, AMCN road tester Norm Lindsay was permitted to conduct the first such test of the model Down Under. Describing the CB750 as “massive, but beautiful,” Lindsay powered from Melbourne to Cape Schanck on the Mornington Peninsula, traversing “wet bitumen, unsealed roads and plain dirt, at times on broken edges looking for trouble.” He found none, summing up the CB750 as “a champion bike”.

Urquhart took the completed CB750 outfit to Phillip Island for the traditional New Year’s meeting on 4 January, 1970, obliterating the field and the lap record to win every start, then repeating the feat at Hume Weir and Calder in the following weeks. At Bathurst, the story was the same, Lindsay and passenger Jack Craig won every start and took no less than 14 seconds off the 75o Sidecar lap record.

In October 1970 came the inaugural running of the Castrol 1000 (Six Hour), and two CB750s entered the Unlimited class, ranged against the traditional British Norton and Triumph big bangers, plus BMWs and the new Yamaha XS1 650 twin. Against all odds, the contest for outright honours came down to a battle between the Triumph Bonneville 650 ridden by Len Atlee and Bryan Hindle, and the CB750 ridden for all but 10 minutes of the race by Kiwi pastry chef Craig Brown, in his first-ever road race, briefly partnered by Roger Jackson. Ironically, the much-vaunted front disc brake proved to be the Honda’s undoing, with the pads shot by the four-hour mark. A botched pit stop to fit new pads saw the Honda drop four laps, while the similarly brake-deficient Bonneville circulated steadily to take the flag from Brown. After the race, Brown and his mates put the Honda back into road trim and he rode it home, ready for work the next morning.

One year later, a Honda CB750 – the new K1 model – did take out the Six Hour after a precision display by Bryan Hindle and Clive Knight, backed up by a well-drilled team from the Brian Collins Motorcycles empire. The winning Honda covered 222 laps – 21 more than the 1970 winner.

The CB750, from the first 1969 models to the final F series in 1978, represents a line of motorcycles that occupy a unique place in history. Honda took the decision to tool up for the four-cylinder model to maintain their position as the most innovative company in the business. Luckily for us, they got it almost bang-on from the outset, and before their rivals could.

The evolution

In reality, the CB750 changed little through the series that culminated with the K6, before the complete makeover than resulted in the CB750F, F1 and finally the F2. And let’s get one thing straight – the original model is not (officially) a CB750K0. The original 1969 CB750 was produced for nearly two years before the K1 came along. K represents the Japanese word kairyo, which means improve or update, hence the K1 was the update of the CB750. However, just to confuse things, Honda built what they termed a transition model, a batch of just 121 bikes, which were identical to the original CB750 except for the use of the rocker-operated carburettor slides and push-pull cables. This, for reasons unexplained, was termed the K0 to identify the difference between the original and the soon-to-be-released K1 and was mainly in response to customer feedback to dealers that the throttle was too heavy.

The visual differences from the CB750 to K1 were mainly cosmetic; the original seat with its raised rear lip was replaced with a flatter version, the midriff side covers, shielding the oil tank on the right and the battery on the left, became more rounded, their badges went from metal to plastic and from the Honda ‘wing’ to ‘750-four’, and the tank badges were slightly different. The major change was under the tank, in the throttle linkage. Originally, a single cable connected to a junction with four separate cables operating the four carburettor slides, which resulted in a very heavy throttle action, with the carbs themselves tricky to synchronise. The K1 system used two cables from the twistgrip to a fixed wheel on a rocker arm that raised the four slides together. Each slide could be individually adjusted and the throttle action was much lighter and smoother. The airbox also changed, with new material to prevent cracking and different mounting mounts.

On the K2, released in Australia in 1973, the exhaust system was altered slightly (known as the 341 series) with non-removable baffles to stop owners blatting around the streets with the baffles removed, and internal mods that slightly restricted the exhaust flow. Locally, the K2 remained on showroom floors for a very long period, possibly too long, as the opposition caught and soon passed the Honda in terms of performance and refinement.

The Kawasaki Z1 was the main culprit, but before long Suzuki abandoned its two-stroke GT750 ‘water bottle’ and released its excellent DOHC GS750, both of which made inroads into CB750 sales. Nevertheless, the K2 made up the bulk of sales worldwide during its lifetime. K3, K4, and K5 models were released in USA, with only minor changes. For Europe and Australia, the K6 was the ultimate rendition of the four-piper, quickly identified by its different tank decals in a panel. Progressively, the K-series got slower, as emission rules tightened and performance dropped, and weight increased.

For a short period, Honda sold the K6 (and K7 in USA) alongside the revamped F and F1 models. Although initially shunned by purists as being a hotch-potch designed to keep the CB750 competitive with the new Kawasaki and Suzuki fours, the F series is now regarded as very collectable machines in their own right.

Honda-what?!

Honda sprang a surprise with its CB750A – the Hondamatic of 1976. Apart from the automatic transmission replacing the five-speed gearbox, the CB750S differed in many ways, with alloy wheel rims and steel mudguards sourced from the Gold Wing, with the frame, tank and side covers similar to the US-model K7. The top end of the engine was the same as the manual transmission bikes, but from the rear of the barrel back it was all-new. In place of the clutch a large casting housed the torque converter. Gears were still shifted manually, but without the need for a hand clutch. The Hondamatic was not a big seller and production lasted just three years.

The force

As well as the civilian versions, the CB750 enjoyed worldwide service as a police model, originally in force in USA and Australia as modified K1s. These models were factory-built and finished in white, fitted standard with crash bars, sirens, and a radio box which replaced the pillion seating. After their police duties, most of these bikes were auctioned off and spent a second life as private transport.

Owning a CB750 today

For a motorcycle that is half a century old, the CB750 still represents a glorious riding experience. And considering the number that ended up as weekend racers, as power plant donors for racing sidecars, or as scrap metal, there are literally thousands still in use. Classic rallies around the country, indeed around the world, are heavily populated by the various CB750 models, and there are a number of worthwhile and discrete modifications that add to the modern riding experience.

One of the 750’s biggest drawbacks is what was originally touted as a major selling point – the front disc brake. Adding a second disc has long been a popular modification but this adds weight and is only a partial solution. However modern pads, braided brake lines, new master cylinders and more recently, replacement disc rotors in better material, have gone a long way to alleviating this while maintaining the required standard appearance. Avon, Metzeler, Continental and several others offer non-radial tyres in classic style but modern construction and compound.

Virtually everything is available from either local providers or a number of international suppliers in Japan, Europe and Britain, meaning restorations can be performed easily. Even the previously scarce original style exhaust systems are now being remade and supplied at an affordable price.

Words Peter Turner Photography Independent Observations