BMW still suffered from a stuffy pipe-and-slippers image as a new race category called Superbike was introduced in America. So when the first race came around at Daytona in March 1976, it was the sporty Japanese and Italian brands that everyone expected would dominate. But the US BMW agent had other ideas – and three secret weapons.

Peter Adams, who had bought the franchise only a few years earlier, took BMW’s relatively new R90S Boxer and assembled a crack race team under the guidance of Udo Gietl, a German-born former racer and NASA engineer who also just happened to have helped formulate the new AMA Superbike regulations. That helped when it came to creative reading of the new rules; Gietl fitted a controversial monoshock rear suspension in place of the usual twin-shock set-up, to the surprise of most, including his own team.

The final piece of the puzzle was a flamboyant 27-year-old Californian rider by the name of Steve McLaughlin. Lured away from the Yoshimura Kawasaki team – not realising ‘Pops’ had merely offered him a prizemoney-only deal – McLaughlin jumped at Adams’ offer of $500 a race plus bonuses and promptly won that historic first race at Daytona. He beat teammate Reggie Pridmore by just a few centimetres in (literally) a photo finish and, while the Englishman ultimately took out the title that year, McLaughlin’s place in history was secure.

Butler & Smith – the company the Adams family had purchased in 1971 – was based in New Jersey on the East Coast and had a division on the West Coast. The company had enjoyed some success in production racing, but it was the arrival of the R90S shaft-drive sportbike in 1974 that gave the company the opportunity to prove its sporting credentials to a sceptical public. Pridmore enjoyed some success in production events, but it wasn’t until the AMA created the Superbike series that BMW really made its mark.

Adams came up with a budget reputed to be a then massive $250,000 – the equivalent of $1.3 million today – to campaign a full race version of the R90S created by Gietl and his team.

A hard winter’s development proved to be time well spent when the bikes made their public debut at Daytona in the hands of Pridmore and slightly-built two-stroke racer Gary Fisher (both chosen by Gietl), with a surprise third entry for McLaughlin. Gietl had intended to run just two bikes with a spare, but Adams insisted on a third rider, to be chosen by the Californian office. There was serious internal rivalry between the company’s two geographic opposites.

This explains why the Californian crew running the third bike were astounded, and irate, to discover that Gietl had secretly fitted the monoshock rear suspension to two of the three R90S Superbikes. McLaughlin had been on the AMA committee that formulated the rules with Gietl and was surprised to see what had been done.

McLaughlin was even more shocked when he discovered that the monoshock bike he was racing had been crashed by Gietl in testing on the street, and was barely repaired.

Pridmore had declined to race with a monoshock because he couldn’t get on with its restricted compliance, and it was widely speculated the team welcomed this in case the tech inspectors rejected Gietl’s creative interpretation of the rulebook and forced them to convert the bikes back to twin-shocker guise. This didn’t happen, but McLaughlin’s mechanic Matt Capri had to work flat out through race week trying to fix the damaged bike. “It seemed each lap Steve ran, something else would break,” he recalls. “He hardly did two laps at a time before the heat race.”

Back in those days grids for AMA road races were determined not by qualifying times but by short dirt track-style heat races, and the BMWs showed their hand with a stunning 1-2-3, Fisher winning easily from Pridmore with McLaughlin in his slipstream.

The following day’s inaugural AMA Superbike final soon saw the three BMWs at the head of the field. Fisher led until a loose exhaust clamp rotated and interfered with his gearchange, causing him to miss gears and over-rev the engine, leading to his retirement with a broken rocker arm two laps from the finish.

This left McLaughlin in the lead, but as a student of the so-called ‘Art of the Draft’, knowing he had no chance of pulling away from his teammate on an identical bike, he allowed Pridmore to lead into the last lap, then lined up to slipstream past him on the tri-oval banking to the finish line [see McLaughlin interview]. He nearly didn’t make it, practically rubbing cylinders with his teammate as the two Boxers droned side by side towards the stripe, but in the final new yards the West Coast monoshock bike just snuck ahead for McLaughlin to win – once the high-speed photo-finish print finally arrived 45 minute later – by three inches, less than the width of the front tyre’s sidewall. Victory came at an average speed of 99.8mph/161.7km/h – just short of the ‘ton’, and some going for a 50-mile test of streetbike-derived speed. Cook Neilson’s Ducati was third, with Wes Cooley’s Yoshimura Kawasaki fourth after wobbling its way past Mike Baldwin’s fifth-placed Guzzi.

The publicity from this 1-2 victory, at a crucial moment at the start of the spring selling season, justified Adams’ investment in the project, with dealers around the country shifting R90S streetbikes as fast as Butler & Smith could deliver them. A substantial proportion of the 17,378 produced in the model’s three years of production from 1974-76, before it was replaced by the full one-litre R100S, were sold in the US that year, and BMW’s fuddy-duddy reputation was literally transformed overnight.

The program also resulted in the championship title for Pridmore, after McLaughlin retired from the second and third rounds. At Loudon he missed a gear and sheared the sheared the flywheel off his Boxer’s engine, then at Laguna Seca he crashed.

On the final lap, with Pridmore just ahead, McLaughlin experienced the full potential of some bigger, better brakes, performing a gigantic stoppie in seeking to avoid ramming his teammate as he closed the door into the last turn. The Daytona-winning bike cartwheeled and flew through the air in one of the most spectacular crashes of all time, having already fortunately decanted its rider. Photographer Mush Emmons captured the moment and when the photo appeared in the Los Angeles Times, it made McLaughlin famous outside the world of motorcycling – for all the wrong reasons.

With the PR mission fully accomplished, and BMW’s image transformed, Adams killed off the race operation. Gietl was sent back to work in the service department but was given permission to run his own team, which enjoyed some success with a R100S ridden by John Long. In fact, Long was declared the 1978 AMA champion, only to have the title handed to the now Kawasaki-mounted Pridmore months later over a startline error at Loudon Raceway when the BMW rider was waved into the wrong place on the grid by an AMA official. So, to most minds, BMW actually won two AMA Superbike titles with their improbably successful battling Boxers.

A ride down history lane

THE chance to finally ride BMW’s original Superbike came at a Luftwaffe airbase to the west of Munich, on an improvised circuit threaded between buildings lining the taxiways, with a hairpin turn to avoid accessing the main runway where aircraft were regularly departing to supply German troops confronting the Taliban in Afghanistan. When you’re BMW, you know how to pull a few strings.

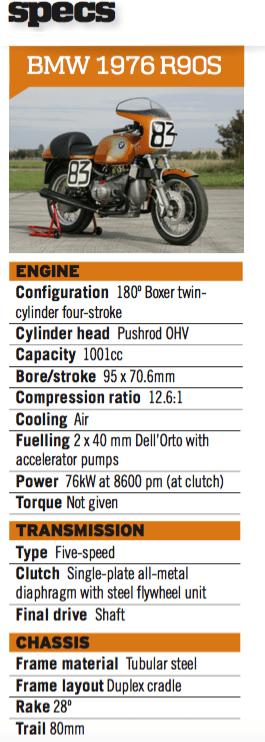

RennBoxer #83 is not some cosseted museum piece, but a living, thundering ride down memory lane, just out of the workshop after a little freshening up for my test.

The stock two-up seat has a large upholstered squab covering the passenger space and the upright riding position is typical BMW. You’re conscious all the time of those two cylinders sticking out either side of the bike in front of your legs, though they don’t much interfere with your feet.

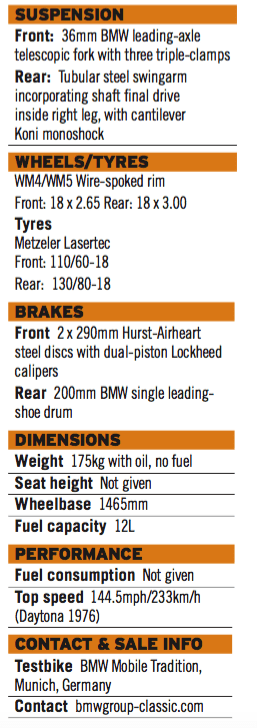

The Boxer engine spins quickly into life with a fruity blat from the long, slenderly tapered twin megaphones. At Daytona it produced 92bhp at the clutch, eventually rising through a season’s development to 102bhp at 8600 rpm – 50 percent more than the stock bike’s 69bhp at 7000rpm – transmitted via BMW’s traditional shaft final-drive five-speed transmission.

To create the R90S Superbike engine, Udo Gietl fitted 95-bore Venolia forged pistons raised in the skirt to help reduce engine width by 20mm either side – good for an extra two degrees of lean angle via the reduced deck height. Capacity increased from 898cc to 1001cc, with a 12.6:1 compression ratio versus 9.5:1 stock. Other improvements included ported heads, bigger (titanium) valves, high-lift cams and 2mm-larger Dell’Orto pumper carbs.

With a 1.5kg-lighter flywheel getting the BMW off the line is easy, but the engine fluffs and stutters if you gas it up hard anywhere below 5000rpm, where those high-lift cams and the megaphone exhausts combine to deliver title-winning performance. Power keeps building towards the 8800rpm redline, where the flat-twin engine remains extremely smooth, with no Norton-type vibes or Triumph tingles.

With liberal interpretation of the AMA Superbike regs, a spacer behind the gearbox moves the engine a massive 25mm forward to load up the front wheel better, though the resultant 48:52 weight bias is still not ideal, and the engine was repositioned 10mm higher for more ground clearance.

The stock 36mm telescopic forks were reworked internally and located even more firmly in the stiffened duplex frame’s heavily gusseted steering head, but even trickier was the monoshock rear suspension. Under pressure from Kawasaki, desperate to help improve the unstable handling of its four-cylinder rocketships, the AMA rulebook permitted ‘relocation of the suspension components’. Directly operated via a triangulated cantilever link, this was arguably the first example of modern monoshock rear suspension.

I found the handling better than expected. It stayed glued to the line in a bumpy third gear sweeper and, while the monoshock has far less travel than a modern Telelever Boxer, it coped with runway rash, even if the ride quality was dismal. But the lack of compliance didn’t cause the bike to hop or skip under power.

It also braked quite well, even if you have to start braking a little earlier and squeeze the lever a lot harder than on a Ducati 750SS. At Daytona the bike ran 260mm twin front aluminium discs with stock ATE single-piston calipers, but they were soon replaced by meatier 290mm drilled steel discs and the era’s benchmark Lockheed twin-piston calipers.

The Boxer twins cruised to victory at Daytona in 1976 over the faster fours because they were a better all-round package – and my ride aboard McLaughlin’s race-winning BMW Superbike underlined that.

STORY ALAN CATHCART – PHOTOGRAPHY ARNOLD DEBUS