Thirty years ago this month, a motorcycle race knocked the nation’s socks off, attracting a race-day crowd of 92,000 and a massive audience on the nation’s leading commercial television network. The next morning, a newspaper in footy-mad Melbourne printed 600,000 ‘run ons’ of its four-page wrap-around coverage. It was that big.

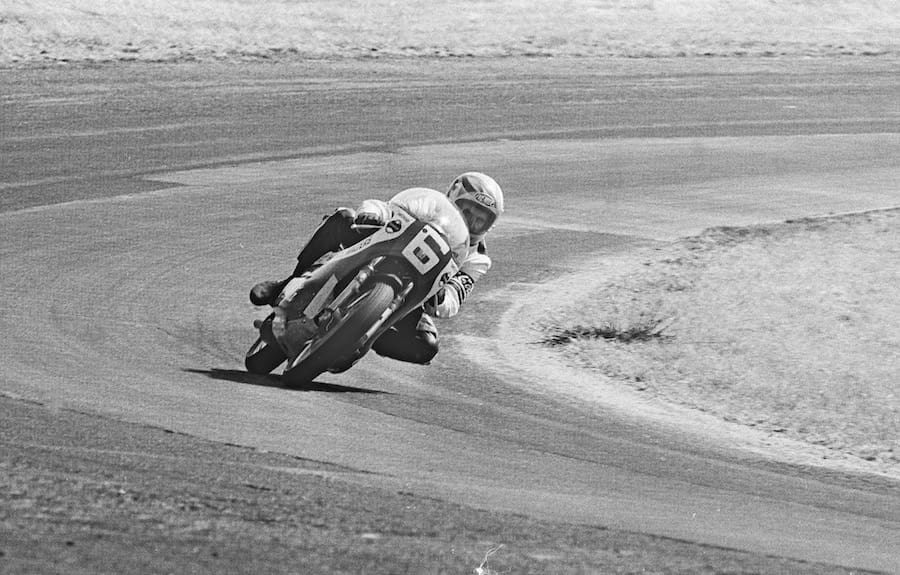

The 1989 Australian Grand Prix had it all… new event, a majestic venue that had been specially rebuilt, 30 laps (48 minutes) of spell-binding racing and a fairytale home-town victory by 1987 world 500 champion Wayne Gardner. There were three more Australians in the next eight finishers.

Grand Prix yearbook Motocourse described it as “Without doubt, one of the greatest Grands Prix of all time.”

Editor Peter Clifford made the telling point: “The Australian interest in the event was greater than Italy ever showed at (Franco) Uncini and (Marco) Lucchinelli, or Britain in Barry Sheene. By comparison, no-one in America knows who Kenny Roberts is.”

On a world timeline, the Berlin Wall still stood in April 1989 and Tim Berners-Lee had just proposed something called Information Management, which he would name the World Wide Web.

The event promoter was 43-year-old English-born civil engineer Bob Barnard. In the race lead up, a French journalist dismissed his expectation of an 80,000 crowd, as the French GP ‘only’ drew 70,000. Barnard told him he’d already sold 64,000 tickets. Some $750,000 worth was bought on the first morning (9 August, 1988).

This flew in the face of previous adverse publicity over police/crowd clashes at the non-championship Easter Bathurst Australian Grand Prix meetings. In 1983, the NSW Police Minister said one option open to police was not to have the races.

Barnard recounts the story of PBL marketing executive Tony Skelton filming the main street of Cowes in 1988, so he could show it with glass in the shop windows, before bikers arrived! Skelton had a different take when ticket sales opened, saying the motorcycle crowd was the most knowledgeable he had dealt with, as people wanted a particular angle from a grandstand seat.

There were other hurdles to overcome. The circuit was 140km by mainly two-lane road from the nearest city, local hotel/motel accommodation was limited, perhaps half the camp sites on the island were held on long-term holiday bookings and many locals were opposed to development. The accommodation shortage had sponsors investigate the feasibility of using cruise liners as floating hotels.

People raised the questions of changeable weather and contractors faced challenges of construction work in damp ground. As well as suiting the then calendar, with Pacific-rim races at the beginning of the season, April was viewed as a having favourable weather.

Running counter to all the perceived obstacles was the pent-up demand for a world championship race in Australia. Hopes for a local round stretched back to tours by top English racers in the mid 1950s, while some had envisaged the 1976 Australian TT at Laverton as a catalyst – until the non-payment of visiting riders and freight charges set the cause back years.

However, Victorian official David White felt it was worth another attempt and said he approached Barnard about holding a race in Victoria. Momentum built with Gardner winning three GPs in 1986, live 500 GP broadcasts beginning with the SBS broadcast of last GP of 1986 from Misano and Gardner’s breakthrough 500 title in 1987. Interest in running a GP spread nation-wide, with the Western Australian government keen to support a race.

When FIM Road Race Commission (RRC) deputy chair Joe Zegward arrived in February 1988 to inspect Phillip Island, he also visited Sandown, Bob Jane’s Calder circuit and Oran Park – for the 1988 World Superbike Championship round.

Keep in mind there was no Dorna to manage commercial and television rights in 1988-89. The RRC allocated races and individual promoters (usually the national governing body) separately controlled TV rights.

Excitement built rapidly, witness these examples. A motel owner in Cowes was stunned when Sydney enthusiasts booked four rooms 13 months in advance and well before final FIM confirmation of the event in October 1988. Members of Ducati Owners Club of NSW chartered a plane to fly into Phillip Island’s cliff-top airport (this was 14 years before Ducati re-entered GP racing). A group from the NSW Central West rented a 22-seat bus and people planned to ride from as far away as WA.

Barnard had runs on the board as a circuit builder and organiser, working on the inaugural Australian Formula One GP in Adelaide in 1985, the 1986 Frank Sinatra headline concert to open the Sanctuary Cove housing development on the Gold Coast and running the 1987 Australian Motorcycle GP at Winton, so his team could gain bike-race experience.

For Phillip Island, he had to deal with a group of men who owned the circuit, the rebuilding process, banks, the Federation Internationale Motorcycliste (since renamed Federation Internationale de Motocyclisme) as well as last-minute dramas obtaining a liquor licence. There was even resistance from at least one of the owners to removing the extensive concrete sections of the old track surface.

The initial rebuild budget for resurfacing, the access tunnel and pit building was $2 million.

“It would eventually cost around $5m for building the track; still ridiculously cheap for a world-class track,” Barnard said.

The redesign shortened the circuit to 4.448km, with the looping Repco Corner replaced by the tight Turn Four/Honda Corner. The late Warren Willing suggested opening up MG Corner, to improve the racing and so riders would not destroy their clutches. Spectator areas were linked, so people could walk the entire lap.

The new-look circuit was used for the final round of the last Swann Insurance International Series on 4 December, 1988. Michael Dowson and Mal Campbell won the races.

And so to 1989. Easter was over 24-26 March and there was no meeting at Bathurst. All interest was on the coming race by Bass Strait. On-track Grand Prix activity at Phillip Island was due to start on Thursday, 6 April. An cloudburst the night before flooded streets in Cowes and turned some camping ground access roads into bogs.

Barnard briefly played traffic cop the next morning as race teams entering the circuit met campers heading to Cowes for supplies. A chapter from Barnard’s as-yet unpublished book on his career says 20,000 people attended on the first day.

“Friday; no traffic jams, everyone doing their jobs, the world was good again and 50,000 people. People walking five miles from Cowes after taking the ferry. Saturday; 10 hours of TV and 70,000 people.”

That was 10 hours of free-to-air television using techniques new to motorcycle racing. Channel Nine had revolutionised cricket coverage and producer Brian C Morelli applied those ideas to bike coverage, with machines filling the frame.

Kevin Schwantz qualified fastest for Suzuki at 1m 34.99s. Using the 107 percent of the fastest time rule, that lap would have seen him qualify for the 2012 race, even with the circuit resurfaced twice since. Sadly for the Texan, he was trigger-happy at the thought of Yamaha’s Wayne Rainey making a first-lap break and highsided out of second position after just two thirds of a lap.

What followed was extraordinary. Rainey led the first third of the race, which morphed into a tremendous battle with Gardner (Honda) and France’s Christian Sarron (Yamaha). Rainey’s Team Roberts teammate Kevin Magee held fourth place but could not quite bridge the gap to the leaders.

At the height of the contest, the leaders were three abreast lap after lap at the end of the straight. All the while the huge crowd was urging Gardner on. It was spine-tingling stuff. But it was the final lap, where Gardner’s staunch determination and the crowd’s raucous will combined to create the frantic fairytale finish. He closed the door on Rainey at the slow corners and had the best track position at MG Corner. Gardner beat Rainey by 0.35 seconds, with 0.47s covering the top three.

There was 1.51s between Gardner and fourth-placed Magee. Mick Doohan, riding with a badly lacerated left hand after falling at Turn Two during practice, was eighth and Michael Dowson (Yamaha) ninth. In the whole of the 1989 season, there was only one closer first-to second finish, at Hockenheim. The Australian GP had the closest top three, top four and top six (12.57s) of the year.

The first Australian world championship Grand Prix had been a huge success. Race teams and the international racing press praised the circuit, event organisation and the crowd involvement. Tony Skelton’s concern about broken shop windows in Cowes had proved groundless.

Jeremy Burgess, Australia’s legendary ex-GP crew chief and who guided Gardner to that significant world title which ultimately paved the way for grand prix racing in this country, remembers it well.

“Nineteen eighty nine was the culmination of four years’ work by Bob Barnard and his crew. He’d been involved in Adelaide with the F1 Grand Prix and lobbied in Europe to secure a GP. It was the fruition of all that work, as well as Wayne’s success in 1986 and world championship in 1987.

“It created an environment in Australia to host an event like that and 30 years later the event is still going strong.”

Words Don Cox Photography Gold&Goose and DC