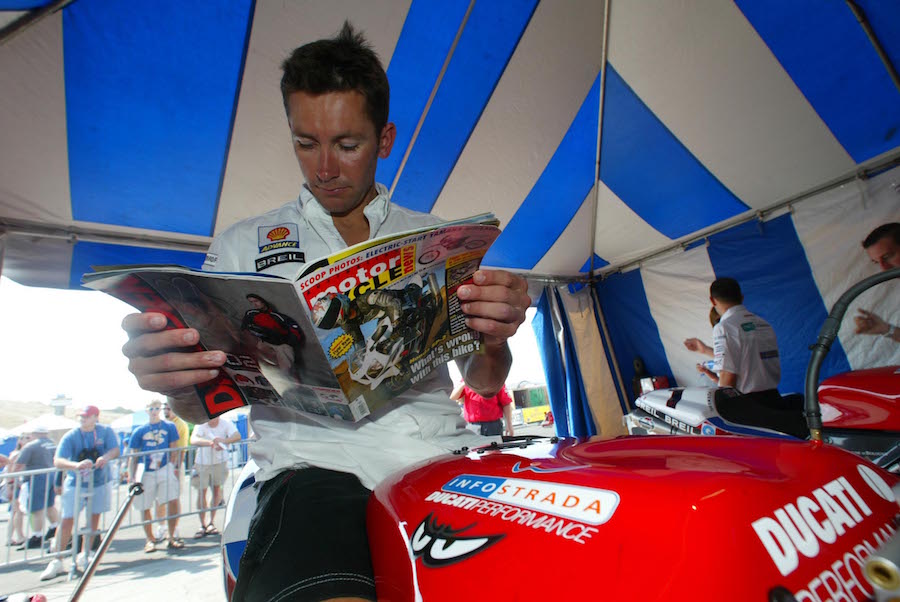

To Troy Bayliss, winning was like a work bonus. While he loved racing motorcycles, he competed on the world stage as a family man. Superbike racing was his job, his income depending on race results.

It’s 28 February 2008 at Phillip Island and Troy Bayliss is about to start another working week in the job with Ducati he’s held for 10 years.

Bayliss is carrying a workplace injury from pre-season testing – a broken collarbone that is slowly healing. But a qualifying crash adds another injury, this time requiring eight stitches in an elbow and extensive strapping.

Undaunted, he quietly applies himself to the task ahead. By the end of this week’s work, Bayliss will have completed a clean sweep of qualifying and the two races. Along the way he will have set the fastest Superbike lap ever at the Island during Superpole and the fastest race lap of the weekend. Over a combined race distance of nearly 200km (double that of a typical MotoGP race) Bayliss will show the true championship-winning potential of Ducati’s all-new 1098R Superbike.

That season he will go on to achieve another three double wins, including at the last round, where he also claims Superpole and sets the fastest lap in both races.

It was a year summed up by the number-21 Baylisstic supporter’s T-shirt worn that weekend. The words on the back read 1098, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 21, Blast-off.

And Bayliss did blast off, retiring as a full-time rider to return to Australia from Monaco because “it was time to put the kids through secondary school”.

Family man

You would expect a father racing to finance his family would become a gun for hire, a motorcycle racing mercenary, but Troy was never like that. Apart from one year in MotoGP on a Honda, he stuck with Ducati throughout his international career.

Last month in New Zealand, at the first of what will be many 30th anniversary celebrations of World Superbikes, Troy explained the long-term relationship with the Italian marque.

“Ducati’s been good to me, and I’ve been good to them,” he says. “We’re a good match.”

Bayliss is a bit bruised and battered from a monster crash in early January testing at Wakefield Park. Observers said it looked like his Panigale had been dropped from a helicopter.

“My bike rode over me,” he says, gingerly touching a red-raw neck. “And I’ve got some work to do on my hip. I’m feeling a bit like Frank Bruno (the 54-year-old British boxer also on the comeback trail).”

None of this seems to deter him. As a long-term Ducati ambassador, his work at the big Classic Festival at Pukekohe includes fast demonstration laps on a locally owned 996RS Superbike fitted with one of his old race engines.

It also involves a constant stream of fans wanting autographs and to share memories with one of Ducati’s favourite sons. Off-track commitments can be as exhausting as competing, but it’s all in a day’s work for Troy, although he starts to look a bit tired as nightfall approaches.

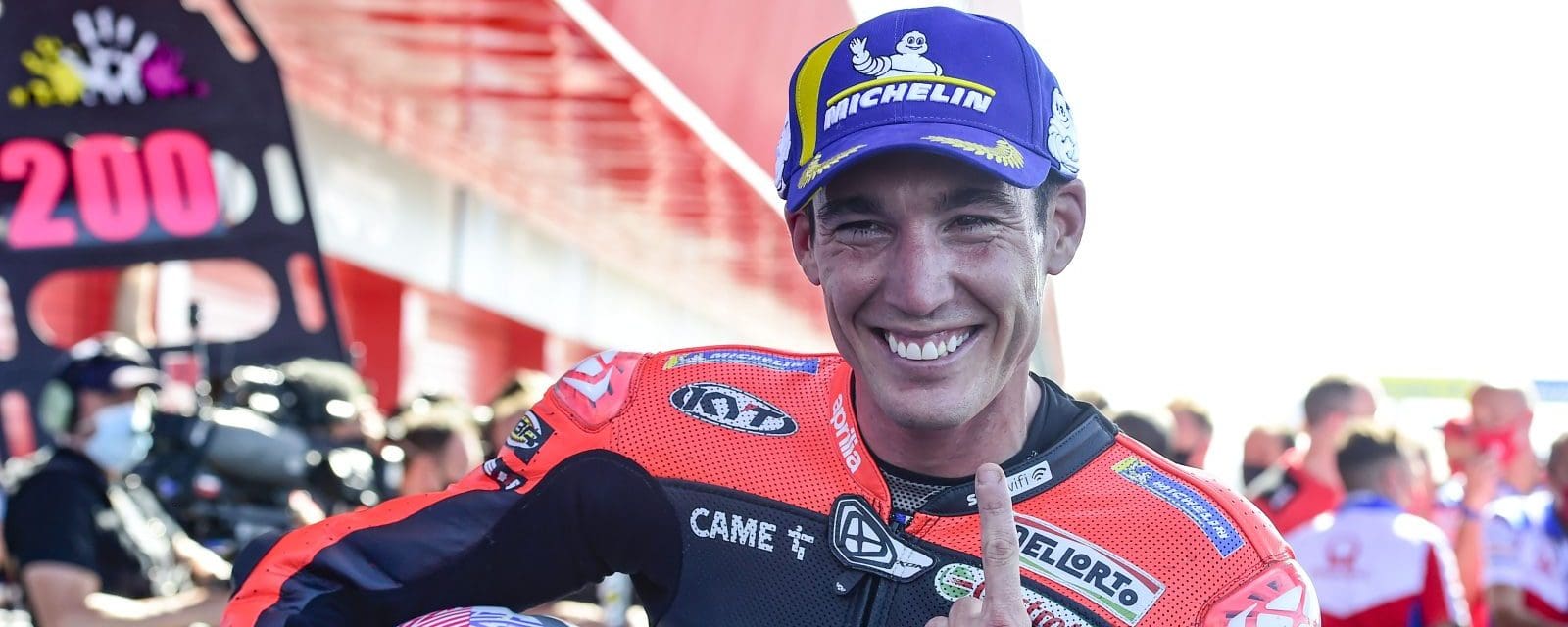

Troy is one of Ducati’s most loved racing heroes.

The former spray painter became a professional racer aged 27, when he was already a family man. He finished runner-up in the ASBK series in 1997, then stunned international racing with a wildcard ride in the 250cc Australian GP. He ran as high as third on an underpowered machine before being relegated to sixth on the run to the chequered flag.

This launched his career path to 52 World Superbike race wins, three championships and a MotoGP race victory. All achieved on Ducati machinery, this also earned him a special place in Italian motorcycling folklore.

At an age when most riders would be thinking of retiring, in 2006 Bayliss achieved the impossible. After clinching his second World Superbike title, Ducati gave him a MotoGP wildcard entry – and he won. This was the first time any rider had won a race in both world championships in the same year, let alone by a reigning champion.

In 2008 Troy won the World Superbike title again on the all-new Ducati 1098.

Troy has always been prepared to roll up his sleeves and get stuck into the task, recently taking on team ownership, the promotion of major motorcycle events in Australia and even riding again this year.

Troy on…

Hey, TB, tell us about…

Telling wife Kim about your race return

“I’d been waiting for the right moment to tell Kim, but one night at the dinner table Oli said, ‘Hey, old man, when’ya going to spill the beans to Mum about racing again?’”

And her reaction?

“She seemed OK with it and said, ‘Whatever; if it keeps you off the beer and gets you fit again’.”

Your kids

“Mitch is a full-time cage fighter (he’s had three fights for three wins so far). I’m not sure where Oli will end up in racing as he’s growing pretty tall quickly. Abbey is a full-time uni student doing a mathematics degree. She’s the smart one but she’s got no money.”

The Bayliss involvement with motorcycle events

“Kim and (long-time business associate) Mark Petersen are going full gas in 2018. There’s going to be some great events with more of a festival feel to them.”

Why you decided to have a go at American flat-track after winning your own prizemoney at the Troy Bayliss Classic

“To see what it was like riding The Mile at full-throttle with no front brake.”

Your riding style

“I ride with my feet sticking out, like Daffy Duck.”

On the huge poster Ducati has on its factory wall

“Mine replaced Carl Forgarty’s and it seemed to stay up there a long time. Maybe they forgot to take it down.” (Or maybe it took a few years for Casey Stoner to win for Ducati).

Humble beginnings

Born in 1969, Troy grew up in rural New South Wales. His first motorcycle was a Honda Z50 his father bought for him when he was four. By age 10 he was racing every dirt class he could on two- and

four-stroke enduros. However, he gave up bikes when he went to high school. It wasn’t until he lost his car licence for a few months in 1990 and took up cycling that he rediscovered motorcycling.

“On my way to work I’d cycle past this motorcycle shop in Taree that had a Kawasaki ZXR750 in the window,” he says. “I borrowed the money to buy it. Then, after a few times washing it and blow-drying it at 200km/h, I started to think I should get off the road.”

Watching the 1991 GP at Eastern Creek inspired Troy to try road racing at 23 years old. The Kawasaki cost $9000, and Troy simply put on aftermarket bodywork – which he painted himself – and hit the track.

He soon realised a 250cc Kawasaki KR1 would be a more suitable bike so he raced (and crashed) that. Then a ZZR600 brought a new focus to the dangers of racing at the top level.

In 1994, he won the second 600cc Supersport race at Bathurst, ahead of Graeme Morris and Wayne Clarke, having retired while leading the first when he ran out of fuel. This meeting made him analyse how committed he was to racing.

“We came out on the track as the first race after the fatal sidecar crash (when Jim Colligan and passenger Ian Thornton were killed) and it was a really hard thing to do,” he remembers.

Troy shook off any self-doubt with a sensational start from the third row to challenge Morris for the lead. The pair swapped places throughout the shortened four-lapper until Morris appeared in front on the last run down Conrod. But Bayliss wasn’t finished. In what would become a trademark braking technique, he went in hard and fast to Murrays Corner, gathered it all up on the exit and won by a whisker.

Troy finished second in the 1995 Supersport title. He entered the final round just one point behind Dean Thomas but crashed.

Troy got his first big break in 1996, joining Martin Craggill in the Team Kawasaki Australia team. He won both races at the second round at Eastern Creek but crashes curtailed his effort and he finished third behind Craggill. Winner Peter Goddard, heading off for international endurance racing, recommended him to Suzuki.

“This was an important year for me as Kim (his wife) and I decided I’d try to make a living out of motorcycle racing,” he says.

By then the couple, married in 1993, had toddler Mitch, so it was a big decision for Troy to give up his job as a spray painter.

He experienced extreme highs and lows in 1997.

Two fifth places as a wildcard in the WSBK opener at Phillip Island were an eye-opener, and in the Shell Superbike Series he led an all-Suzuki podium at Phillip Island and started the ARRC (ASBK) Superbike title chase with double wins at Baskerville and Phillip Island.

However, he crashed at Lakeside, breaking a vertebra in a vicious highside. He clawed his way back for a championship showdown with Craggill at Mallala but missed out on the title by just half a second in the last race.

His efforts were rewarded with a wildcard entry in that year’s Grand Prix at Phillip Island.

And epic shoulder-to-shoulder battles with Ralf Waldmann and eventual champion Max Biaggi put Bayliss on the world map.

Could have raced GPs

Offers to join the GP paddock flowed in, but there was a catch. “We had to bring money, starting at $200,000. It just wasn’t an option.”

An unexpected call from Darrell Healey, the owner of UK Ducati team GSE, was the game-changer. The Bayliss family, now with infant Abbey, uprooted from Australia to begin a 10-year odyssey working overseas.

Under the guidance of crew chief Colin Wright, also responsible for helping Neil Hodgson and James Toseland to the top, Troy battled the culture shock of the damp and dangerous UK tracks.

But another person was key to his success.

“I’d be standing there looking out the window at another rainy day and Kim would kick me out of the house to do my cycling training,” he says. “She kept me going in a difficult first season.”

Troy nominates Kim and Ducati team manager Davide Tardozzi, who has been involved with him since 1999, as the biggest influences on his career.

Tardozzi first met Troy at a dreary Knockhill round of the British Superbike Championship, and later said he was impressed with the Aussie’s work ethic, which began at 8am when not a lot of people had surfaced for the day.

Bayliss won the 1999 BSB title, after a previous season hampered by crashes and bike reliability.

To secure his first superbike crown, he had seven wins, including two doubles, winning the title by 28 points from Chris Walker, followed by John Reynolds and GSE teammate Neil Hodgson.

The three amigos

Three Italians played a crucial role in Troy’s international career. Ducati’s Tardozzi, Paolo Ciabatti and Claudio Domenicali signed him to race in the AMA championship. It was a crucial time for the company, trying to expand its worldwide sales reach at a time when important new models were about to be released.

Bayliss and family happily set up a new home, this time in sunnier surroundings.

The job ahead was never going to be easy, with another year spent adapting to new tracks and a new lifestyle. But Troy soon revealed his single-minded attitude.

Few tracks are as intimidating as Daytona. Approaching its 31-degree banking for the first time is like riding at top speed towards a wall.

In 2000 Troy fronted it for the first time in a pre-season tyre test on the Vance & Hines Ducati Superbike. Asked if the infamous track’s challenges were playing on his mind, he said: “I can’t be bothered with all that, I’ve got a wife and kids to support.”

Bayliss was the fastest rider that day, and followed it up a month later by setting pole for the Daytona 200 ahead of Mat Mladin and Nicky Hayden. Watched by Ciabatti, he led half the race before crashing. Soon after, another phone call came through and Troy was taking over injured Carl Fogarty’s ride in World Superbike team.

It took a few races for Troy to find his feet after being knocked down in the first two, and he admits it was Kim who kept him motivated.

The breakthrough didn’t come with a win but two stirring rides at Monza. Some desperate earned him two fourths and the respect of a partisan crowd.

“Monza, Imola and Brands Hatch are my favourite tracks,” he says. “They all have some slow corners where the spectators are really close and that lifts me like I can’t describe.”

Two weeks later he won for the first time at Hockenheim, but Brands Hatch, Foggy’s old home ground with 100,000 fans, was always going to be tough. But not for Troy, who came first and second in the two races, earning this comment from King Carl: “He wants to win and hates to lose, so some similarities to me, I guess. I’m just glad I don’t have to race him.”

The following year Troy took Ducati’s fight to defending champion Colin Edwards, who was racing Honda’s VTR1000 SP V-twin. Six wins earned Bayliss his first World Superbike title. Ducati was back on top.

Troy started 2002 in dramatic fashion, winning eight of the first 10 races. However, Honda brought in a new version of the 999cc engine and Showa upgraded the suspension package. Colin Edwards won the last nine races to take the championship.

Their final showdown at Imola is still considered one of the best confrontations in the series’ history and afterwards Edwards summed it up: “Troy’s given it everything today when he knew we (Honda) were in better shape.”

Meanwhile, Troy spoke about his planned move to Ducati’s inaugural MotoGP effort: “I’ve been in World Superbike for three years now, I’ve had a really good time and the atmosphere is very friendly. I’m sorry to be leaving it, and I will certainly miss it”.

MotoGP misadventure

The Bayliss family had been considering Troy’s possible retirement. He had often been quoted as saying “racing is a job, a championship win a bonus”, but the MotoGP offer was too good to refuse.

Loris Capirossi took the Desmosedici GP3 to a podium on its debut and a win five rounds later to finish the championship fourth overall. Bayliss was sixth and missed out on Rookie of the Year honours by just two points to Hayden, who finished more races but had fewer podiums.

The next year was a struggle, both for Ducati’s technicians, trying to tame the Desmosedici’s savage power output, and its riders. Capirossi slumped to ninth in the title standings while a series of crashes found Bayliss in 14th – and out of the team. With no Superbike options (the factory had re-signed 2004 winner James Toseland and runner-up Regis Laconi) Bayliss found his way to Sito Pons’ satellite Camel Honda MotoGP squad.

He showed a flash of the old brilliance at Laguna Seca – he qualified fourth and was running second before being relegated to sixth – but missed the last six rounds through injury and finished only 15th in the final standings.

Meanwhile, over in World Superbike the return of Suzuki and Yamaha had amped up the series and Ducati’s dynamic duo of Toseland and Laconi were reduced to fourth and sixth. The factory was a lowly third in the manufacturers title.

Bayliss was drafted for 2006 and almost single-handedly regained the world titles for riders and manufacturers. He had 12 wins, including eight in a row, on a model that was nearing its use-by date.

“The 999 felt almost like a GP racer,” he remembers. “It was high-revving to stay competitive with the 1000cc four-cylinders and its engines only lasted 450km.”

Ride of his life

The family thought twice about an end-of-season offer to return to MotoGP as a wildcard at Valencia to replace the injured Sete Gibernau.

“I thought it might be a cool thing to do,” Troy says, “but we had some talks over the money we’d be paid and who I’d have with me.”

In typical Bayliss fashion, the deal was simple. The higher he finished the more he’d be paid, and he wanted the three people he wasn’t allowed to take to MotoGP previously.

So his championship-winning Superbike engineer Ernesto Marinelli was joined by Davide Tardozzi and Paolo Ciabatti in what would be Troy’s 45th GP appearance.

“I took my Superbike handlebars and suspension settings, jumped on the bike, and we progressed from there,” Troy says. He qualified ahead of Desmosedici veteran Capirossi to claim second on the grid behind Valentino Rossi.

“I was a bit worried after Sunday warm-up as I was only 13th,” he says. “But the crew settled me down by saying the Bridgestone tyres (which Troy had not used before) were no good for this sort of session. I had a crazy good start and my biggest problem was keeping Loris at bay. He was like a dog with a bone.”

With Rossi having crashed out and Troy leading, Ducati had a 2017-Lorenzo-Dovizioso-type dilemma. Honda rider Marco Melandri was closing on Capirossi and, with Hayden cruising to his first world title, one option would have been for Bayliss to let Capirossi past to cement third place in the championship.

The order from the pit wall never came and Capirossi managed to hold out Melandri at the flag to finish the season one point ahead.

Ducati president and CEO Federico Minoli summed it up later: “This day will go down in Ducati’s history. This is the first time we have had a one-two finish in MotoGP, the first time we have won the first and last races of the season, and our best-ever championship finish.”

Bayliss took a remarkable win, by 1.3sec. “I had to force myself to keep smooth and stay under control,” he recalls. “In the last few laps I had to say to myself, ‘This is happening’. It was so special and a great way to end the 990 project that Loris and I had started.

“I had the same feeling in my last Superbike race at Portimao two seasons later.”

By Hamish Cooper

PHOTOGRAPHY Phil Aynsley, Gold&Goose and AMCN archives