The dominance of 500cc two-stroke machines in grand prix racing came to an end in 2001. The following year 990cc four-stroke prototypes were allowed to join the grid heralding in the new MotoGP era, which means this season marks the 20th anniversary of Honda’s first MotoGP bike, the RC211V. Initially dominating MotoGP, the RC211V claimed the riders’ title in the hands of Valentino Rossi in its first two attempts and was raced until 2007, when new rules were introduced and the maximum engine displacement was reduced to 800cc.

According to project leader Tomoo Shiozaki, the basis for the RC211V design was a Honda V6 prototype from 1988, called the FXX.

“This was a study project, with main goals being compactness and mass centralisation,” begins Shiozaki. “We developed it into a rideable prototype and it performed excellently. It delivered a significantly higher performance and, according to our test riders, it handled better than the 750cc RC30 V4 we were comparing it with.”

But a production version of the FXX would never become reality, because the RC30 was proving hugely successful in world Superbike, endurance and Formula One racing so there wasn’t any need to replace it. An added bonus was the high market demand for motorcycle racing replicas, which the RC30 also covered, and so the FXX project came to an untimely end. But it wasn’t all lost, because it went on to form the basis of Shiozaki’s RC211V.

“The most important choice at the start of the project was the configuration of the engine. I chose a five-cylinder because the regulated weight limit for four- and five-cylinder MotoGP racers was set at exactly the same value: 145kg. For a six-cylinder, another 10kg had to be added [and] we didn’t want that extra weight. We didn’t like a triple, despite the fact that it could be lighter, but five cylinders could deliver more power than three or four, so that was the reason for our final choice.

“In addition, a V5 has what we call a functional habitat that suits a motorcycle well. This habitat is the immediate space around the engine block, in which not only can additional functions be placed, such as an alternative airbox, but also, for example, heat can be dissipated and cool air can circulate. Mass centralisation and mass compactness were the starting points of the design and the lessons learned with the FXX formed the outset for this.

“We were very successful doing so, the final V5 engine design of the RC211V created many options for placing the engine in the frame. Multiple angles are possible, theoretically it could even be mounted upside down without changing the riding characteristics much. This gave a lot of design freedom for the rolling chassis.”

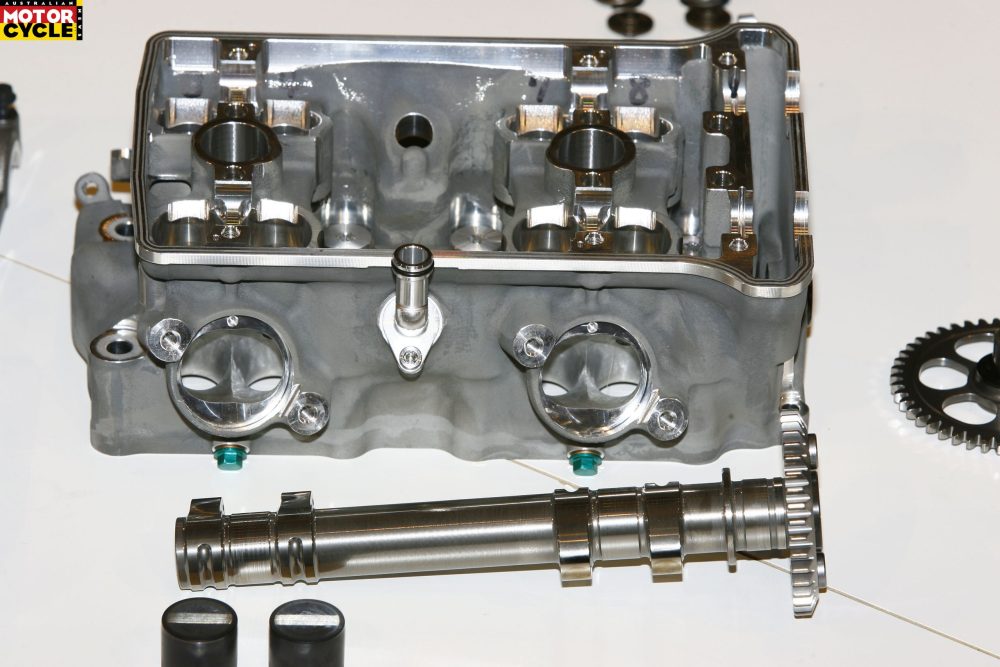

The V5’s layout has three cylinders facing forward and two facing back. The vee angle of 75.5° made not only for a more compact engine, but also provided spot-on primary balance, eliminating the need for power-sapping balancer shafts. Technically, the RC211V was related to Honda’s RC45 WorldSBK racer sharing the same 72 x 46mm bore and stroke and using a similar shaped combustion chamber. The big-bang technology came from Honda’s successful NSR500 V4 two-stroke racer, which allowed the rider to make much better use of engine power and take full advantage of the increased torque.

Shiozaki opted for a semi-dry sump. Though in the same engine case, the crankcase in which the crankshaft rotates is fully separated from the gearbox. The engine oil is located in a reservoir in the gearbox, underneath the gear cluster. He chose this to reduce pumping loss and to prevent blow-by as much as possible.

“During combustion, high pressure is created on the top of the piston, the combustion gasses push the piston down. It’s impossible to prevent a very small part of these gasses from being blown past the piston rings into the crankcase, along with small droplets of fuel and oil. This blow-by costs engine power and increases the crankcase pressure, but with semi-dry-sump engine, this happens less.

“In addition, the semi-dry sump allowed us to keep the crankcase more compact, which makes the crankcase stronger and which contributes to a high power output and a better durability. The oil level in the gearbox cavity remains more stable compared to a wet sump and there is also no need for a separate oil tank.”

The RC211V’s V5 engine was shorter than a V4 as well as being narrower and much more compact than an inline-four cylinder. Like its competitors, it featured double overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder. The valves were closed with valve springs, although in 2001 there were already experiments with pneumatic valve action.

“Choices we made for the fuel injection and the engine management system also were done to enhance the handling of the motorcycle,” explains Shiozaki. “We placed two multiple hole atomising injectors in the inlet tract for each cylinder, one above the throttle valve, which operated at full throttle and one below the throttle valve for better performance in the low- and mid-rev ranges.

“The fuel pressure was variable, we could control it continuously. Based on this continuous ECU control, we designed the inlet tract and the exact position of the injectors in such a way that when opening or closing the throttle, a certain amount of fuel actually remains in the intake ports between each engine cycle. It clings to the inner surface of the inlet ports until the inlet valves open for the next cycle. This optimised gas response for the rider and had a positive effect on the engine’s power output.”

“The engine management system needed to be very advanced to cope with this technology,” Shiozaki continues. “It was the first of a new generation. We found out that a good setting massively contributed to the throttle response and with that the dosage of engine power. This greatly improved the rideability of the bike. The system could be programmed very easily, which turned out be a bigger advantage than expected when traveling from track to track and dealing with so many different atmospheric conditions. In the end we managed a maximum power output of just over 220hp at 14,000rpm and an estimated engine life of 120km. The power delivery was very smooth and from the lower revs straight up to the higher revs the huge amount of torque remained intact. The V5 configuration played a big role in that, but also the design of the exhaust system.”

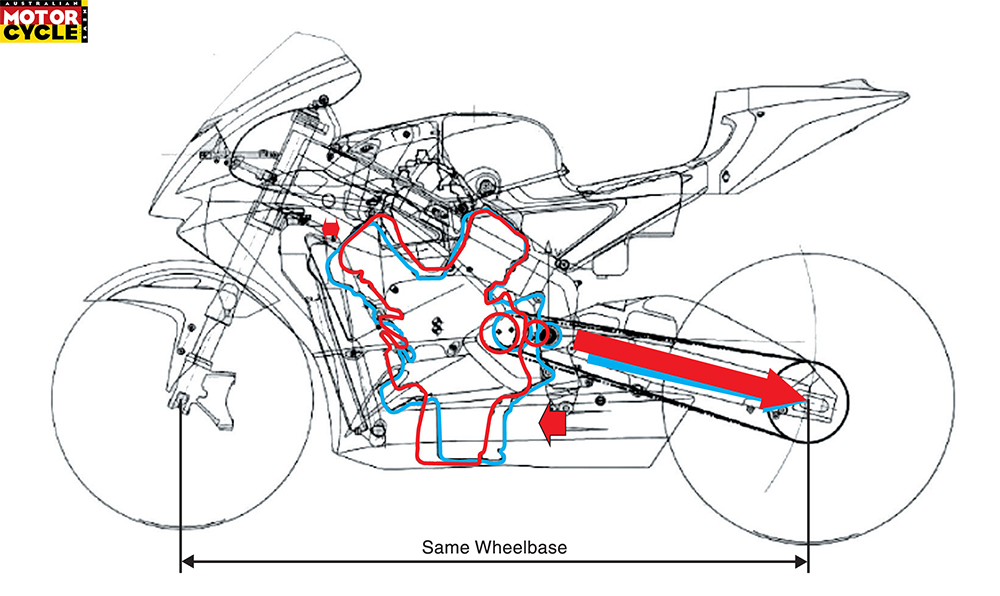

Although electronic rider aids didn’t really start appearing until 2003, the RC211V used a slipper clutch in combination with a six-speed gearbox which was operated by a quickshifter. The chassis was a further advancement of the NSR500 chassis, but the RC211V’s 1440mm wheelbase was 40mm longer. The overall layout of the aluminium twin-spar frame was not only determined in conjunction with the engine, but also with the most ideal location of the fuel tank within the chassis.

“The starting point was again mass centralisation. The fuel tank was placed for one-third under the rider’s seat and as close as possible to the motorcycle’s centre of gravity. As a result, an increasingly emptying fuel tank doesn’t disturb the handling as much.”

According to Shiozaki the chassis was designed with emphasis on longitudinal stiffness. This was specifically done to make the chassis slightly more flexible at higher lean angles, which enhances the control of the bike during sliding.

“Together with the new frame we also designed a new Unit Pro-Link rear suspension and a new aluminium rear swingarm. Compared to the NSR500’s conventional Pro-Link system, we eliminated the damper mount on the upper cross-member and placed the rear shock in a much more vertical position.

“We did this so we could further improve mass centralisation and also optimise the positioning of the bike’s overall centre of gravity. The new Unit Pro-Link also boosts the action of the suspension at the extreme angles the bike is under while cornering. With this design, high cornering suspension control is not dependent on the roll angle of the bike and when accelerating out of turns it also has a positive effect on the bike’s roll behaviour, which it stabilises.”

Computer Aided Engineering (CAE) played an important role in the design of the new frame and swingarm.

“Through CAE simulations we determined the most ideal lateral and torsional rigidity values. If we compare these to the NSR500, the frame had 17 percent less lateral rigidity and 23 percent more torsional rigidity. For the swingarm these values were 12 percent less lateral and 29 percent more torsional. We did this for a very good reason, because the flex of this combination feels very natural to the rider, especially under cornering.”

The aerodynamic bodywork was wind-tunnel designed because unsurprisingly, Honda “wanted to keep it as slim and small as possible,” says Shiozaki. “Aerodynamics, engine cooling and the handling of the motorcycle formed the starting points of the design. In addition, we also wanted to be able to change the gearbox without disassembling the entire fairing.”

Carbon-fibre brake discs and Nissin four-piston brake calipers initially provided the front-end’s stopping power but later, Brembo calipers were also used. The instrument cluster was minimal, it consisted of a rev counter and a digital display indicating the lap time and engine temperature. On the left clip-on ’bar was a three-way switch that allowed the rider to choose between the different engine mappings. One of these mappings significantly reduced the engine power to enable an effective race start.

“All in all, you can say that a perfect balance in all aspects of designing and engineering a motorcycle was our priority at the time,” Shiozaki says. “Everything was designed in conjunction with each other, the engine, the chassis, the bodywork, as a complete motorcycle.”

The reactions of the riders who used the RC211V in the new MotoGP World Championship were positive. Despite the high engine power, the machine was described as docile and neutral, with decent road holding. Torque was said to be imposing, yet controllable. This was due to the RCV211V’s rather flat torque curve, which also ensured a relatively long rear-tyre life and, more importantly, allowed the riders to maintain easier control while sliding.

In the inaugural MotoGP season Honda’s RC211V was victorious from the start, winning the first race of the new four-stroke era at the Japanese GP at Suzuka, Japan. Valentino Rossi (Repsol Honda) took the win in soaking wet conditions and went on to rule the 16-race season with a further 10 wins.

Rossi’s title win showed domination, but riders who were allocated RCVs later in the season also did well. The late Daijiro Kato (Fortuna Honda) took a close second-place finish in his first race with an RCV in August’s Czech GP, while Alex Barros (West Honda) won his debut RCV race at Motegi, beating Rossi in a thrilling last-lap duel, even though he had only ridden the V5 for the first time during Friday morning’s practice session.

Thanks to Valentino Rossi’s 11 wins and teammate Tohru Ukawa’s single victory, Honda also won the 2002 Constructors World Championship, the company’s first four-stroke constructors’ title since 1966. The fastest machine in the inaugural MotoGP season was Ukawa’s RC211V, reaching a speed of 324.5km/h at the Mugello circuit in June 2002.

How it got its name

RC stands for Racing Cycle; the 211 indicates it was Honda’s first GP racer of the 21st century, while the V has three meanings; the cylinder layout, the roman numeral for five and, of course, V for victory.

The 2003 season

How the bike evolved

As the seasons went on, the RC211V evolved, but the basics were kept intact. In 2003 modifications to the combustion chamber, valve timing and other components resulted in a power output of 230hp at 15,800rpm. An electronic engine braking system appeared to create smoother cornering characteristics, and the factory experimented heavily with exhaust systems that season. And as well as the introduction of a steering damper, there was an updated fairing to create more airflow to the engine’s main cooling radiator.

How the riders performed

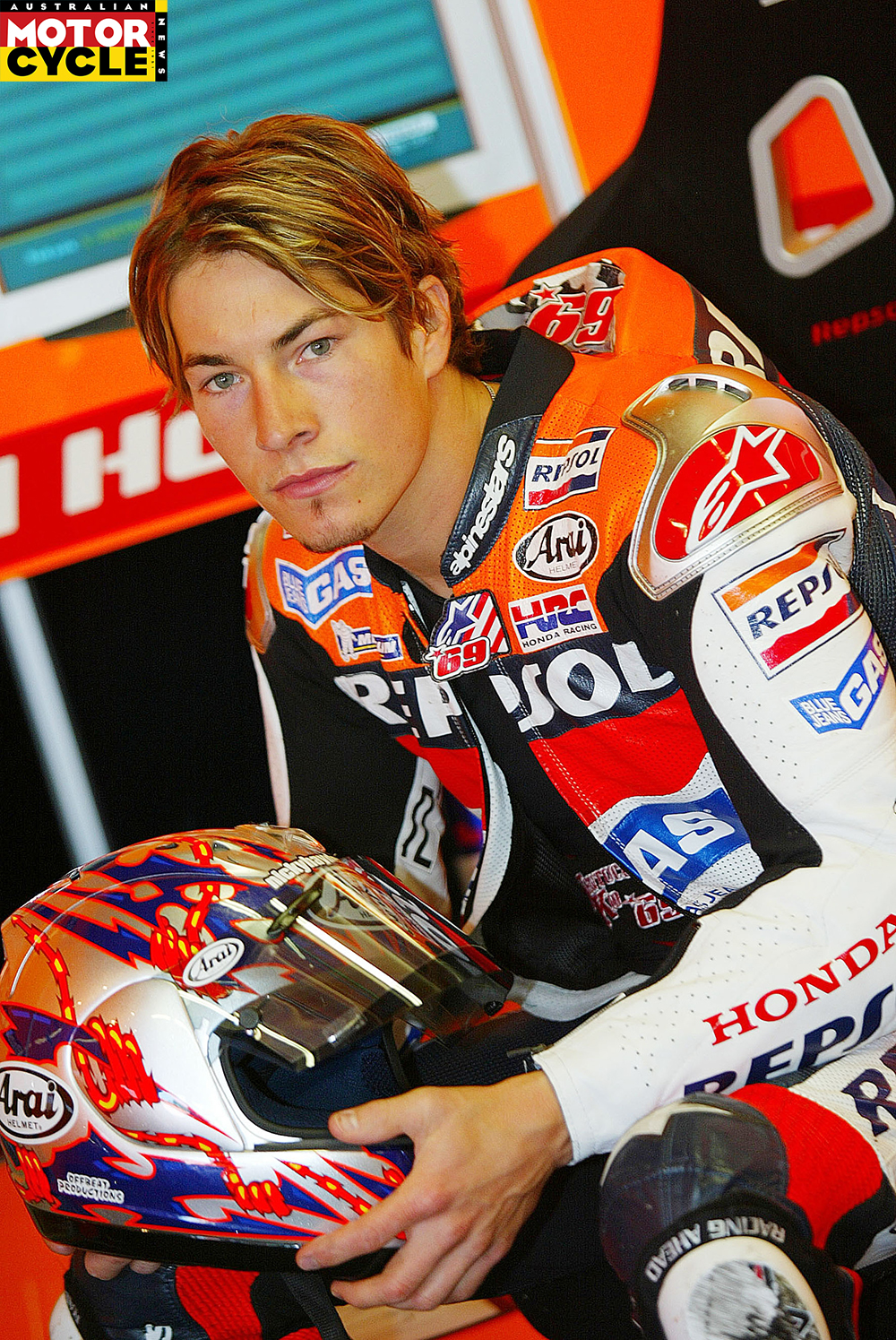

Six riders contested the 2003 MotoGP series on the RC211V, taking four of the top five positions in the World Championship. Three riders won 15 of the 16 races: Valentino Rossi (Repsol Honda), Sete Gibernau (Telefonica Movistar Honda) and Max Biaggi (Camel Honda). Honda and Rossi won their second successive MotoGP riders and constructors titles. Rossi had a new teammate in 2003, reigning US Superbike champ Nicky Hayden, who scored two podiums in his debut MotoGP season. In 2004 Valentino Rossi made his well-publicised switch to the factory Yamaha team.

The 2004 season

How the bike evolved

The 2004 RC211V engine was thoroughly reworked in a bid to reduce reciprocating weight. A new 5-into-4 exhaust system improved torque but also increased power to 241.5hp at 16,000rpm. Honda’s Intelligent Throttle Control System appeared, while the frame and swingarm also underwent a number of changes throughout the year, as Honda experimented with geometry. The new fairing was more stable at high speeds and improved manoeuvrability.

How the riders performed

While Rossi proved his point by running away with the 2004 riders title with Yamaha, Honda did successfully defend its constructors title with the RC211V. Sete Gibernau had his best premier-class season yet, winning four GPs to take second overall on his Telefonica Movistar RC211V, ahead of Max Biaggi (Camel Honda), Alex Barros (Repsol Honda) and Colin Edwards (Telefonica Movistar Honda). The RC211V filled five of the first six places in the overall ranking that year. Barros clocked the highest RC211V speed of the season: 343km/h at the Italian GP at Mugello.

The 2005 season

How the bike evolved

In response to Valentino Rossi’s championship on board Yamaha machinery, Honda opted to redesign both the engine and chassis for 2005, using the season to refine the bike for 2006. As well as a smaller and lighter engine, new bore and stroke values of 76 x 43.6mm saw power increase to 253hp at 16,000rpm. The ITCS system was developed to have the two rear cylinders controlled by ride-by-wire, while the front three maintained cable control. The more compact engine meant that with the same 1440mm wheelbase a longer swingarm could be used to allow for a wider range of chassis settings.

How the riders performed

Rossi again won the riders world championship with Yamaha and again RC211V riders completed the overall podium. It was Marco Melandri who finished second this time with his Fortuna RC211V, followed by factory Repsol Honda rider Nicky Hayden. Max Biaggi finished fourth on the second works RC211V, in front of Colin Edwards on a Yamaha.

The 2006 season

The last for the 990 RC211V

For the 2006 season some minor changes in geometry were made as well as further refinement to the electronics to enhance traction, engine braking, cornering and acceleration. The fairing was slightly altered to improve handling characteristics. With the new-generation RC211V, Nicky Hayden won both Dutch and American MotoGP races and also finally wrestled the riders world title off Valentino Rossi for the first time since the Italian joined the premier class. Dani Pedrosa replaced Max Biaggi for the 2006 season, but was given a base model, often referred to by HRC as the ‘Original’ version. Basically this was a further refined 2004 RC211V, fitted with an updated chassis featuring minor changes in geometry and a slightly reworked version of the 2005 electronic control system. Pedrosa won two grands prix on the so-called Original, lofting the trophy at both the Chinese and British GPs. Casey Stoner reached a speed of 334km/h on his LCR RC211V during the Italian GP at Mugello.