Does a bike built to a price feel like a compromise? Does restricting its performance for the Australian and New Zealand LAMS market dilute the riding experience? Is the 2021 Triumph Trident 660 a step forward in technology and performance in the entry-level segment or is it just a clone of the main players?

To find out AMCN attended the official Australian Trident launch, which involved two days of riding across all the types of roads Australian riders will ever encounter. From freeway cruising, to high-speed backroad sweepers and clattering into rippled hairpins on the run up to Victoria’s Mount Baw Baw ski field, the Trident was subjected to the best – and worst – of Australia’s roads.

Before I rode I got a detailed presentation from Triumph Australia that underlined its aggressive intent to take on the main players at the premium end of Australia’s LAMS market.

It is very rare for marketing staff to mention rival brands directly but Triumph makes no bones about challenging Yamaha, Kawasaki, Honda and Ducati. Constant references to Yamaha’s MT-07 twin makes it easy to assume that Triumph considers this the current LAMS benchmark in Australia.

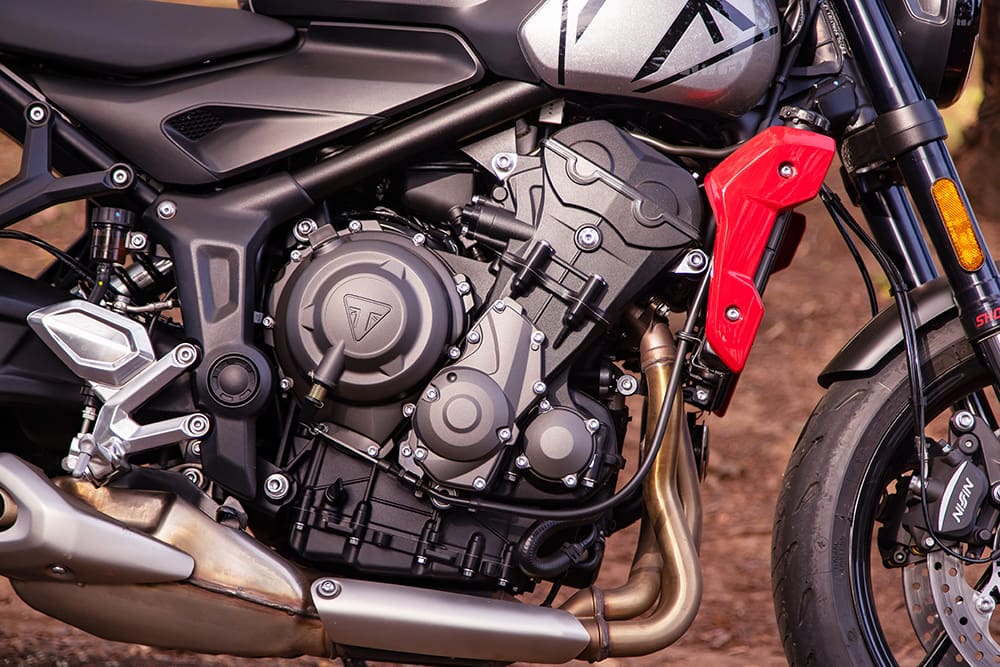

The presentation gave me the chance to view the Trident up close for the first time. Its styling is crisp and refreshingly distinctive. The more you look at it the more there is to see. Such details as the MotoGP-style exhaust, sculptured petrol tank, aerodynamic-looking front mudguard and a stylish TFT dashboard add layers of class.

The person responsible for the styling is Italian designer Rodolfo Frascoli. He has been an integral part of the Trident’s four-year development cycle and it shows. Frascoli has previous form with such diverse projects as Moto Guzzi’s Griso, Vespa’s Granturismo and Suzuki’s born-again Katana.

His work with Triumph has involved several models. Frascoli has brought cleaner lines and a hint of heritage to the current Triumph range. You only have to look at the revised Rocket 3 to see what I’m talking about.

The Trident packs elements of several current and historic Triumphs into its design. For example the rear swingarm area with its taillight and numberplate holder looks like a similar arrangement on the Rocket. This contrasts with the knee cutouts and associated plastic pads on the petrol tank, which reference the cutouts and rubber knee pads of a mid-60s Triumph twin.

The effort put into the styling has other benefits as well. There are no loose wires or cabling, mismatched bolts and other fittings you sometimes find on a bike built to a price.

So the quality is there. So is the physical size, because the Trident certainly doesn’t look like a small, entry-level model. That is an important factor for Australia’s LAMS riders, who want to quickly transition from tiny bikes within that range to larger ones without blowing the budget.

A lot of this is due to that large petrol tank, which also gives the Trident a slightly menacing, British bulldog attitude. That tank is actually a cowling covering an integrated fuel tank and airbox. In order to meet Euro5 emissions laws while simplifying production and keeping maintenance costs down Triumph opted for an automotive-style fuel induction system.

This has single-port injection on each cylinder but only one main throttle body. Crucial to the effectiveness of this system is the airbox, which has been specially designed for this application. Its shape demands more space above the engine, hence the faux tank.

There is no shying back from the fact that Triumph is proud of the Trident. Its logos are boldly displayed on various key components. It even has Showa logos on the front fork and Nissin calipers, although these are basic versions of what these famous companies have to offer in suspension and braking.

Do the technical aspects match the quality of the styling? At first glance they do.

Triumph has managed to build to a price using ingenuity and the experience of 15 years manufacturing of its 675 and 765 triple-cylinder engines.

Forget Triumph’s previous LAMS-approved Street Triple 660. That simply was a destroked 675 and was priced nearly $3k higher than the new Trident.

As we have reported before, the Trident is a heavily revised version of its long-running series of triples incorporating over 67 new components. Tuned for torque and linear power it has also been designed for long service intervals (after the initial break-in period of 1000km) of 16,000km.

Enough of the theory, now for the practical.

As I suit up for the ride a small feeling of trepidation creeps over me. Covid has kept me away from a motorcycle launch and riding in unfamiliar places for nearly a year now. Today I am heading from suburban Melbourne, dodging the mid-week work/school run to get to the Yarra Ranges and its claustrophobic, narrow roads, with the final destination Mount Baw Baw.

Perhaps I’m feeling like any newbie LAMS rider out for the first big adventure, or an older rider just out for a week-day ride as a reminder about how good it is to be on two wheels.

As I head off there are two immediate impressions; the Trident may look like a big bike but the low seat height (805mm), slightly cantered-forward riding position and 189kg wet weight makes it feel very manageable.

As I drop the (slipper) clutch and blend with flowing, multi-lane traffic, rather than feeling asthmatic at low revs there is a punch of torque pushing me forward. Triumph claims more than 80 percent of the Trident’s torque is available from 3600rpm. You better believe it.

A simple white-on-black LCD readout displays speed, revs and fuel level. Below it a colour TFT screen displays gear position, the time and set-up menus. Simple and effective.

An hour later I’m into the narrow twisties of the Yarra Ranges. Once I’ve shrugged off the constraints of several villages and blind entrances to hobby farms a series of well-cambered, uphill bends beckons my throttle hand.

The engine spins up freely and the exhaust note chimes into that three-cylinder howl that is a Triumph trademark that has echoed across five decades. It’s surprisingly loud and shows that an engine can meet Euro-5 laws without sacrificing its soul. Internal engine modifications have eliminated much of the mechanical noise of the older Triumph triples, allowing the exhaust note to take centre stage.

And that tenor-like wail underlines that fact that the Trident is the only three-cylinder engine in the LAMS class. The day winds on like the roads. Perfect early autumn weather makes me just want to keep riding. Eventually I’m on the run up to Mount Baw Baw. This road is a bit special. Later this year it will host the Mount Baw Baw Sprint, a round of the 2021 Australia Tarmac Rally catering for modern, classic and showroom-spec cars.

So now I’m riding up the course that a million-dollar sport will take over in November. If there are any failings in the Trident, this switchback ski-field access road will reveal them in the blink of an eye.

It doesn’t matter if you ride a mountain road in attack mode, fast cruising or dawdling along with your eyes on the scenery. Roads that are more often damp than dry in summer, wet in autumn and spring, and buried in snow in winter are always a challenge to ride.

The Trident handles these conditions with ease, with the traction control only activating a couple of times to flatten the power as it squirms out of a damp, shaded corner. However the ABS is never activated.

The triple’s strong torque delivery means you don’t have to chase gears to keep the momentum going. You can also cruise along at low revs while you admire the long-distant views.

Basic suspension is put to the test when I hit a patchwork of bitumen repairs. A few times I get kicked up off the seat slightly by a large bump but the Trident stays on line and the chassis never feels overstressed.

The non-adjustable front end works fine and even under hard braking remains stable. I need to change line suddenly as a ute cuts the corner on a narrow road, the Trident obeys instantly. The only small issue I find is that the seat shape seems to want to push me towards the tank.

Next day’s riding is on high-speed, open backroads across the dairy country near Warragul, followed by a short freeway run back to base. The Trident had felt nimble up in the mountains and now it feels rock solid cranked over on the cambered sweepers. The riding position is fine for freeway work and the torque means the engine isn’t working hard to get into the fast lane. It’s obvious the Trident was subjected to a lot of testing in real road conditions before it was put into production.

This is a model that deserves to sell well in a very competitive market segment. It may very well have set a new LAMS standard with category-leading features such as road and rain riding modes, traction control, fly-by-wire throttle, a high-spec TFT dash and full digital lighting.

Triumph Australia staff said it expected its rivals to soon up the ante to match it. But right now the Trident has a clear advantage.

Test Hamish Cooper Photography Ikapture