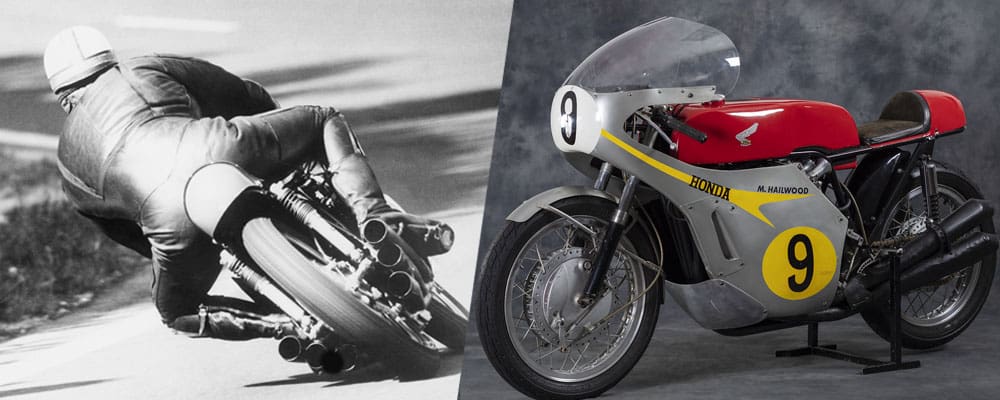

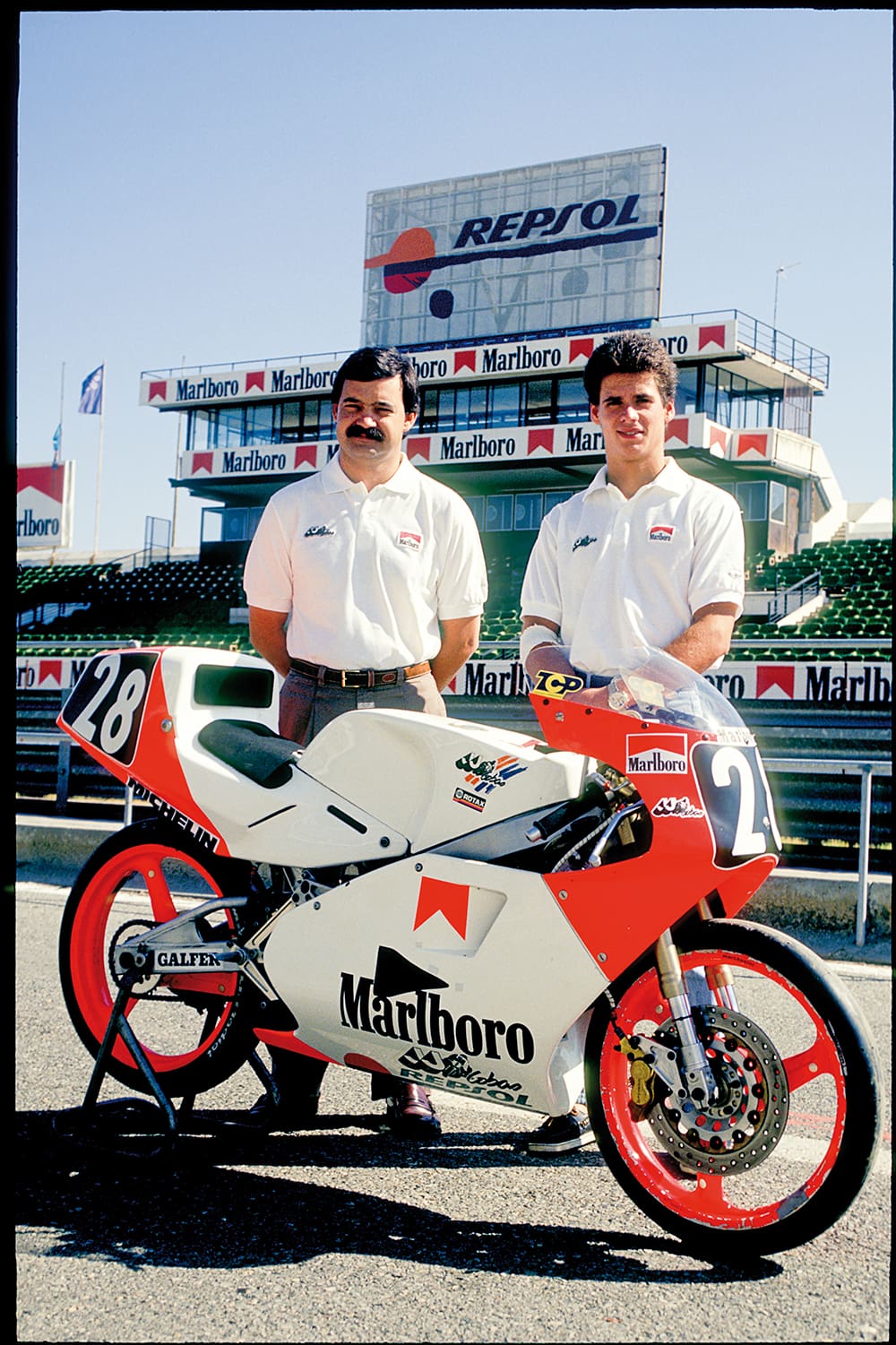

At the age of 19 years and five months, Alex Crivillé (pronounced Cree-vee-lay, not Criv-ill) did more than just rewrite the history books by becoming the youngest-ever world champ in 1989.

It was also the first time a Rotax-powered motorcycle took out a world crown, defeating the well-funded Derbi squad and the mighty Honda factory team run by HRC.

By clinching the championship at the last round in Brno, Crivillé also brought recognition to arguably the most influential chassis designer in Grand Prix history, Antonio Cobas, as well as the most enthusiastic sponsor anywhere in biking – Jacinto Moriana (aka JJ, the bike-mad owner of a major Barcelona car sales empire, JJ Automóviles).

The victory must be the ultimate achievement of what the Italians call a moto artigianale – a bike built from proprietary parts by a single-rider privateer team using a self-built chassis.

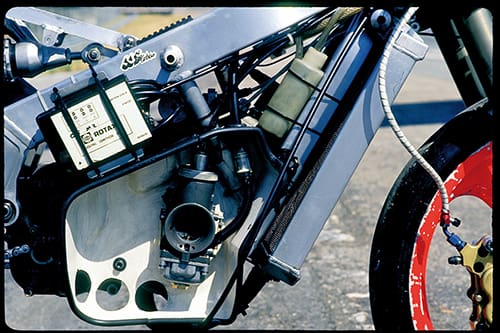

Originally, the JJ-Cobas team had no intention of contesting the 1989 125cc World championship, since the TB5 had been designed as a customer racer. As well as his work as Sito Pons’ race engineer, Antonio Cobas was advising the Minardi Formula 1 team on chassis design, in between developing a JJ-Cobas 250GP racer powered by the team’s own 250cc V-twin engine designed by Eduardo Giró, which was nearing completion after a three-year gestation.

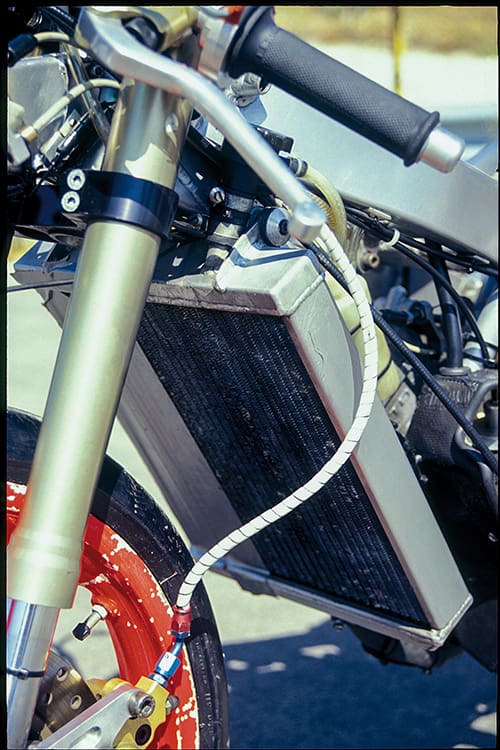

But Crivillé’s sacking from the Derbi team changed all that, and when the decision was made to go GP racing that season, there was only three months before the first race in Japan. Accordingly, Crivillé’s bike was very close to standard for the first couple of races, even using 18-inch wheels and standard tyres to score its debut victory in Australia, before Michelin started supplying its special 17-inch rubber (a front crossply and radial rear from the Spanish GP onwards). This required Antonio to alter the suspension and steering geometry to suit, but apart from that and the upside-down White Power forks that became available for that season, it was a stock TB5 chassis – just a fraction heavier at 67kg half-dry.

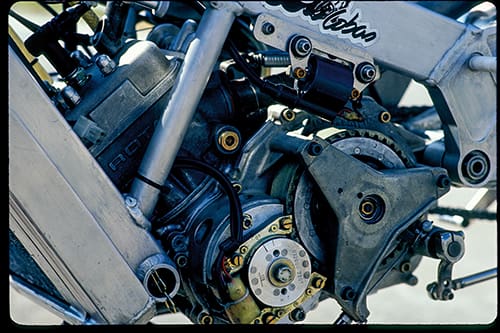

Eduardo Giró’s work on the stock Rotax engine was only slightly more extensive, concentrating on expanding the usable power band, and improving overall performance. He retained the standard five transfer/three-exhaust, eight-port Rotax cylinder without modification, but bored the Dell’Orto flat-slide carb out to 39mm, and modified the crankcase to permit a larger inlet tract with altered rotary valve for different port timing. Long hours on the test bed produced a new exhaust pipe that the team ended up racing with all season long, even though Giró brought slightly different ones to almost every race for them to try.

The standard pistons were replaced with special Mahle ones to give higher compression, matched by new cylinder-head inserts. A carbon-fibre airbox was developed to optimise carburation, but a key modification was to replace the standard radiator with a much bigger one constructed out of a Renault 5 Turbo unit, to enable the Rotax engine to run as low as 45°C, Giró’s ideal temperature reading. These modifications raised the standard Rotax engine’s 28.7kW (38.5hp) output at the gearbox to just

over 29.8kW (40hp).

“Once we saw how competitive we were in Australia, our policy from then on was to take as few risks as possible mechanically,” Cobas explained. “We had to make sure the bike would finish each race, and that meant sacrificing possible performance gains if we weren’t completely certain of their reliability.”

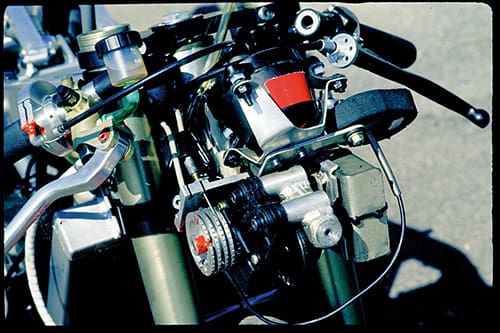

As an example, the team employed the same standard Rotax digital ignition offering a choice of four different pre-programmed curves through the entire season, rather than risk a more sophisticated but unproven computerised system which presented an infinite choice of curves via a pre-programmable microchip. It offered superior power delivery, but was never actually used in a race.

“Getting dismissed by Derbi was the worst day of my life,” Alex Crivillé told me.

“I felt such a fool, as if I’d thrown away my one and only chance of becoming World Champion. But the following day, when they demonstrated their faith in me by establishing a team from the ground up simply to go Grand Prix racing with me – me! – as the only rider, it was like I’d been born again.

“I grew up into a man in those 24 hours, and stopped behaving like a child.

“Then, when I broke my collarbone in the very first race in Japan, I was disheartened – but not despondent. I knew the season was a long one, and that I could recover from that setback.

“I made sure from then on that I didn’t make any more mistakes and, except for crashing in Italy, I don’t think I did.”

Austria’s first World Championship-winning bike

…and it felt like this

Taking the JJ-Cobas for a test ride at the Jarama GP circuit in Madrid, straight after the bike won the championship, the machine felt well-balanced and practically spacious – if you can use that term for such a tiny bike with a 1270mm wheelbase. Even someone of my height could actually get their head under the screen down the main straight.

The balance

Because the TB5 offered such a neutral stance, it was less tiring to ride hard for any length of time because you had less body weight on your arms and shoulders. The weight distribution was 54/46 percent when the bike was static, but with the rider in place this became nearer to 50/50.

The stable and predictable handling was aided by conservative steering geometry, with a 24° head angle and 98mm trail.

It felt predictable, smooth and forgiving, with little vibration. It was a bike that seemed to respond to your thought processes almost before you’d issued them, yet could deliver a light slap on the wrist to stop you exceeding either its or – more likely in my case – your own limits.

The suspension

The degree of sensitivity offered by the White Power inverted front fork sent a message that the chassis relayed faithfully, while at the rear, Cobas’ progressive-rate rear suspension had a precision and sense of control completely missing from the RS125R, Honda’s less sophisticated cantilever rear end.

The brakes

The single 280mm Zanzani front steel disc, gripped by a four-piston Brembo caliper, gave ample braking performance even with my extra weight aboard – so much so that once I started to get brave it was all too easy to lift the back wheel if I grabbed too hard and too late.

The engine

JJ-Cobas’s Rotax engine also offered a big increase in rideability compared to the similar rotary-valve Derbi I’d ridden the year before, rivaling Gianola’s reed-valve Honda in terms of flexibility and torque (not usually a word used about a 125 single!)

The engine pulled smoothly from 8000rpm up to just over 13,000rpm in a way that belied its rotary-valve format.

The power valve was obviously responsible for this flexibility, but unlike on 250GP Rotax engines I’d ridden, fitted with the same porting and pneumatic exhaust valve, the Cobas didn’t have a step in the powerband around 10,500rpm when the on/off valve came fully open (or closed, depending how you look at it).

Instead, there was a completely smooth transition that was presumably due to the more refined operation of the electronically-controlled system.

The advantage of such a punchy motor became apparent when I tackled the steep hill behind the pits at Jarama.

With the gearing fitted, I had a choice of revving it hard in third, in which case I’d hit the 13,000rpm redline just as I crested the hill under the bridge.

The front wheel lifted way off the ground as I did so, and I had to change up at an inconvenient moment while trying to avoid running off the edge of the track, as well as cope with the wheelie!

Better instead to short-shift into fourth at about 10,500rpm, then let the engine’s strong midrange power carry you up the hill before grabbing fifth appreciably sooner for the run up to the blind La Ciega right-hander. The smooth and torquey delivery of the Giró modified Rotax engine was all-important.

The gearing

Rotax offered a wide choice of ratios even as standard – seven each for first and second gears, four for third, and three each for the top three ratios.

Even this wasn’t enough for the Cobas team, who had the Austrians make them two

extra choices for each of the top two and bottom two ratios, as well as an alternative primary-drive ratio.

With all this potential to become hopelessly confused, it wasn’t surprising Antonio Cobas said he had to spend the first few test sessions after Alex signed up with them teaching him how to set up a gearbox.

“Derbi had too much going on to be able to spend the sort of time with someone as young and inexperienced as Alex was in order to teach him how to do this,” Cobas said. “We made 18 gearbox changes alone in our first couple of test sessions, before he began to understand what it was all about.”

Call it step one in the steep learning curve that took the young Spaniard to the 500cc World Championship exactly 10 years later with Honda’s NSR500, in 1999.

Story Alan Cathcart Photography Emilio Jimenez