Brits are pretty good at inventing things, but much less good at commercialising them. From penicillin through to the internet, there are literally hundreds of British inventions which either people in other countries have brought to the marketplace and profited from, or else have disappeared into the what-might-have-been trash can of history owing to lack of financial support. And the designers of the Wooler Flat Four 500 are no exception.

In post-WW2 Britain, a 500cc ultra-lightweight four-cylinder motorcycle was conceived which was completely practical and unique, incorporated many intelligent features and delivered a level of performance and comfort years ahead of its time. Yet, despite its design being offered to Britain’s existing manufacturers, then enjoying a boom in sales both at home and abroad, the 500cc Wooler Flat Four never reached production.

And it was because its creators lacked the resources to produce it themselves, and the British manufacturers preferred to keep on building their existing models, whose designs were mostly rooted in the past, but safe in the knowledge they could sell every one built. Time, and the arrival of the Japanese the following decade, would prove how short-sighted that was – so instead the 500cc Wooler Flat Four has become another fascinating footnote to the Motorcycle history book.

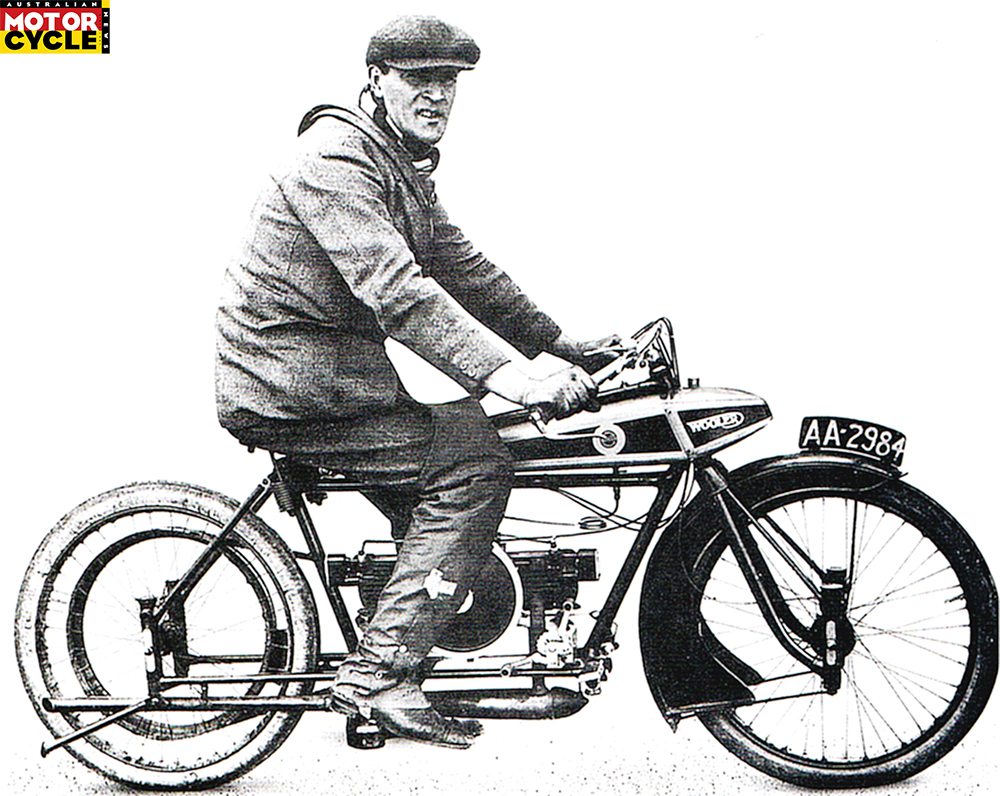

John Wooler was born in 1883 in Chiswick, West London. As a young man, he worked for Napier, builders of the fastest and most powerful cars money could then buy – a prized job which cemented his love of motorised performance. Wooler built his first motorcycle in 1902 by purchasing a powered pedal-cycle DIY kit, followed by his own design of three-wheeler in 1904, with a forecar seating arrangement. But Wooler’s dream was to build his own motorcycles, so in 1909 he quit his day job in favour of working a night shift to allow him to work on his motorcycles during the day. In 1911 the first of these, the Wooler Two Stroke – christened ‘the rocket’ after its unique styling – made its debut at the London Olympia Show.

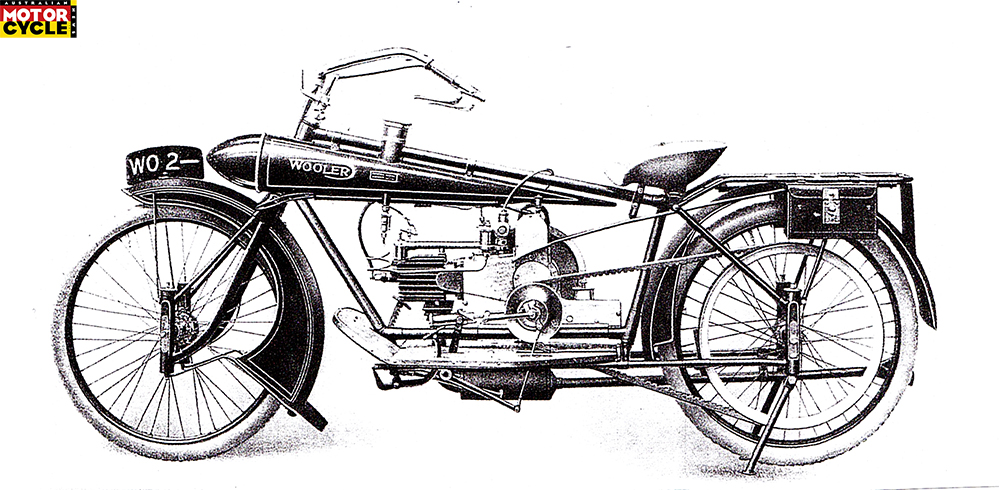

The torpedo-shaped fuel tank protruded forward beyond the steering stem, a feature carried through on all future Wooler models, same as the tubular-steel cradle frame with – amazingly for the time – plunger suspension front and rear. Equally avantgarde was the variable-ratio final drive via expanding pulleys, while the 233cc two-stroke engine’s single horizontal cylinder was closed at both ends, to become a charging pump to force induction without crankcase compression. No wonder the Olympia press reports stamped the Rocket as ‘the most conspicuously novel model on display, with a grand number of innovative features’.

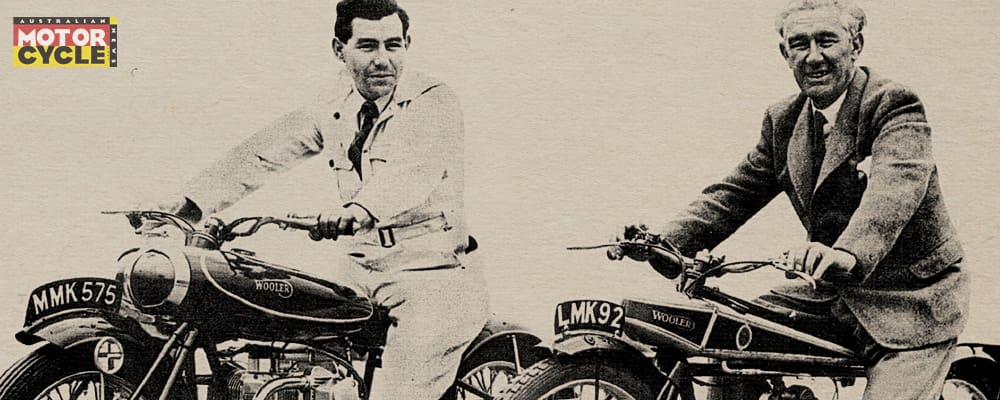

In a small factory, Wooler began satisfying the several orders he’d received. But, in a recurrent theme throughout his life, he was grossly undercapitalised. So he arranged with the nearby Wilkinson Sword company to take over producing the bike with a 345cc version of the two-stroke engine, but it lasted less than a year, leaving Wooler and his brother Charles to again go it alone. Around 100 examples of the Two Stroke were built before 1915, when the company switched to war work.

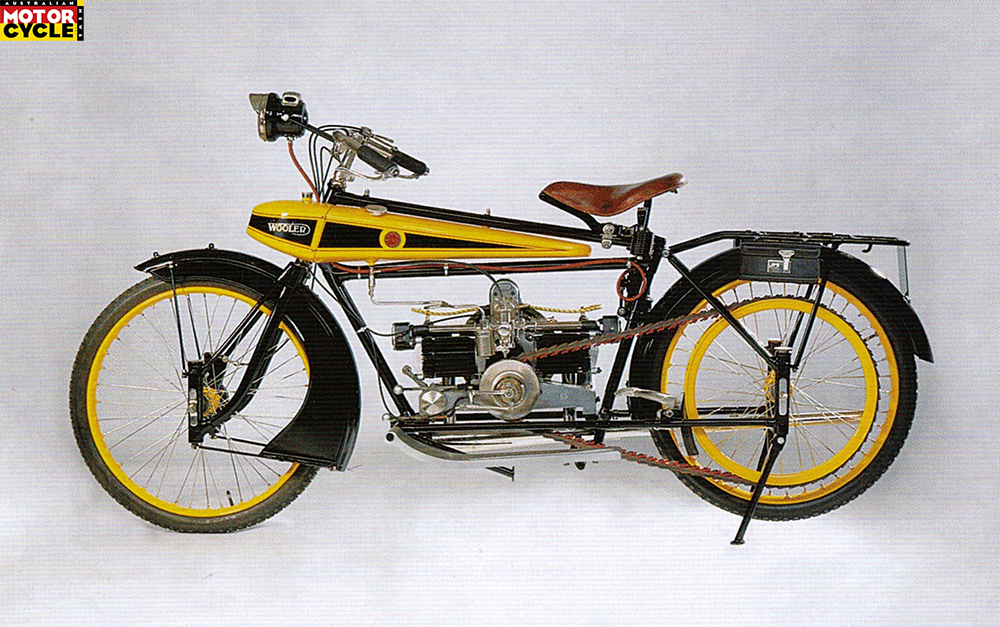

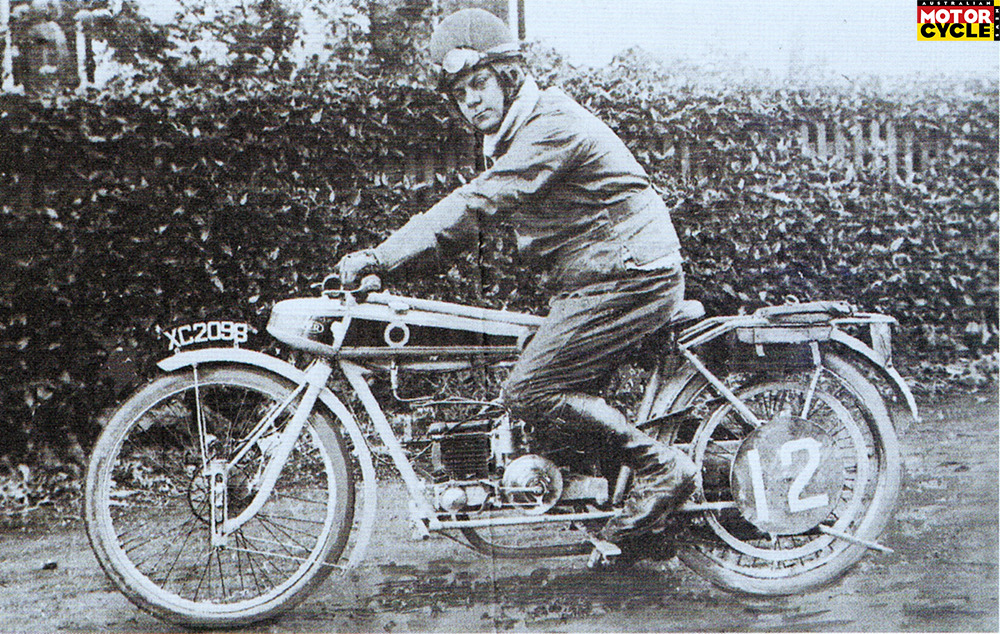

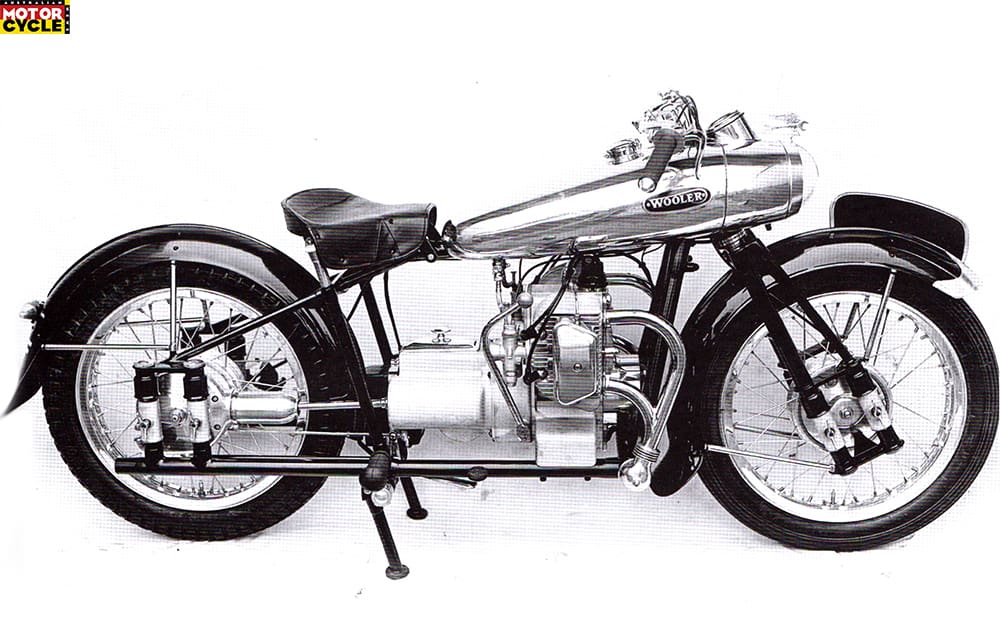

During the war years, and together with an ex-Napier colleague John Hull, Wooler designed his first four-stroke, a 350cc fore-and-aft, inlet-over-exhaust flat twin. This was eventually reputed to produce 18hp at 7800rpm and was installed in a beefed-up version of his Two Stroke frame. It boasted the trademark torpedo tank painted a bright yellow and black, which led motorcycle guru Graham Walker to christen it ‘the Flying Banana’ when it appeared in the 1921 IoM Junior TT, the same year John Wooler’s son Ronald was born.

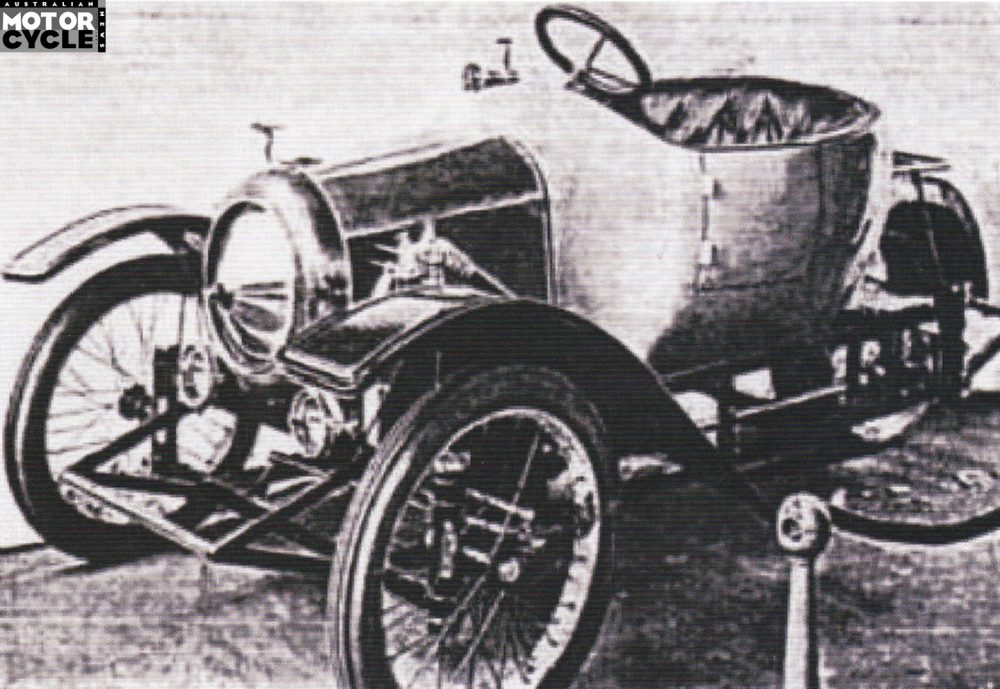

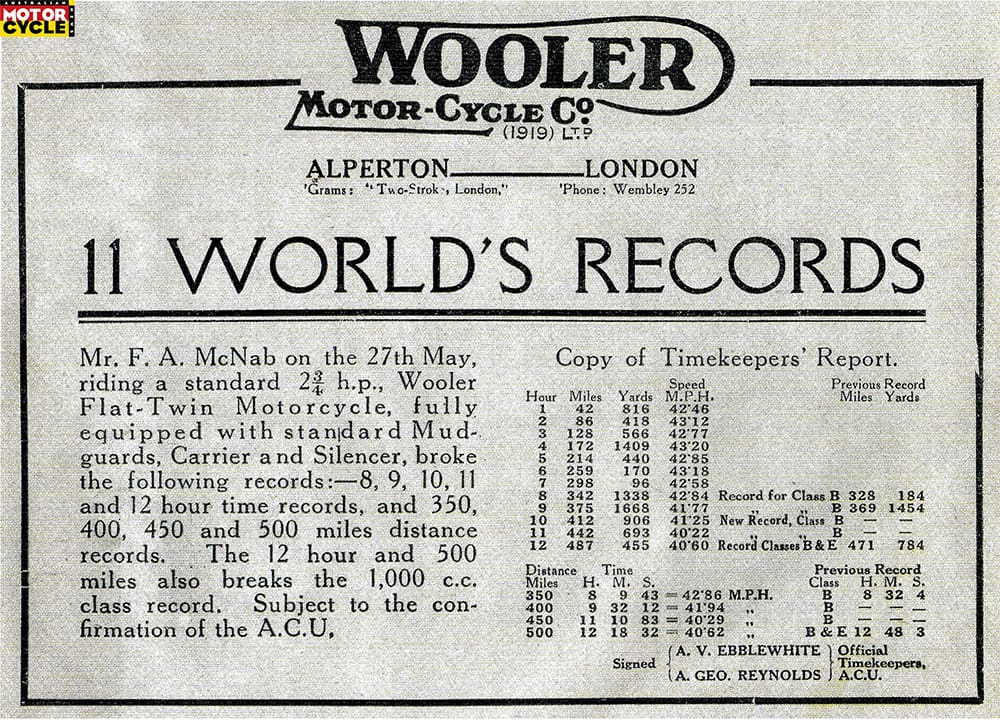

John Wooler had launched the Flat Twin in November 1918 and, thanks to the Wooler Motor Cycle Company’s £200,000 flotation, was ready for series production. However, the 1919 debut of the 1098cc Flat Twin-powered Wooler Mule cyclecar failed to gain traction – just a handful of examples were built – and ate into precious capital. But Flat Twin sales were initially good, however not good enough to keep the company in the black.

In 1922 railway magnate William Dederich bought into the Wooler Company and recapitalised it. This funded development of an overhead-cam 350 Flat Twin and a 500cc version, but like many other such concerns industrial conflict during the postwar slump meant the Dederich Wooler Company was wound up in 1923.

Wooler tried again, this time with a 511cc face-cam single which only existed in prototype form, and in 1926, John Wooler turned his back on bikes, to work as a freelance design engineer specialising in diesel aero engines and automatic transmissions for cars. In 1936 he designed a series of mopeds for the former Wooler importer in Denmark, but otherwise kept busy on consultancy work for defence contractors.

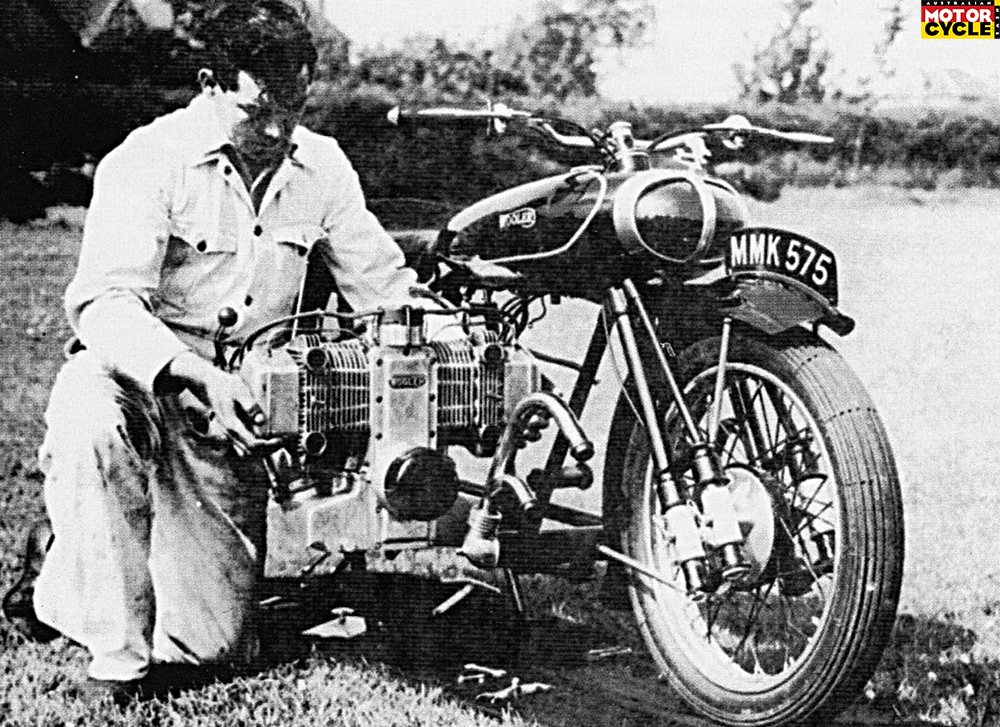

That is, until his now motorcycle-mad son Ron persuaded his dad to pay proper attention to a motorcycle he’d been working on since returning from Denmark. Quite different than anything conceived before – an ultra light horizontally-opposed 350cc flat-four. By now the pair were living together, their Bungalow home also their design studio, with a well-equipped workshop out the back.

And so on 16 February 1948, the Woolers unveiled their prototype Light Four in running order to the press, prior to its display at the Earls Court Show later that year. Claimed to weigh 108kg, this device saw the opposed pairs of cylinders stacked one above the other, and while tall, the engine measured less than 510mm in width, and weighed just 34kg complete with its unit construction four-speed gearbox. Instead of two crankshafts, two pairs of short conrods pivoted on a centrally-mounted T-shaped beam. The rocking leg of this T-beam operated a normal crankshaft and flywheel assembly via a single conrod, which then drove the rear wheel via a shaft final drive.

The advantages were light weight, reduced vibration, continuous power delivery and decreased friction, with minimal side thrust to the cylinders. Bevel gears at the front of the crank drove a vertical camshaft to operate the valves, with two stacked pairs of forward-facing exhaust ports. Top speed was claimed to be 145km/h, though no power output was quoted, and the flat car-type combustion chambers in which the valves sat parallel to each other didn’t hint at that level of performance from a 500cc motor.

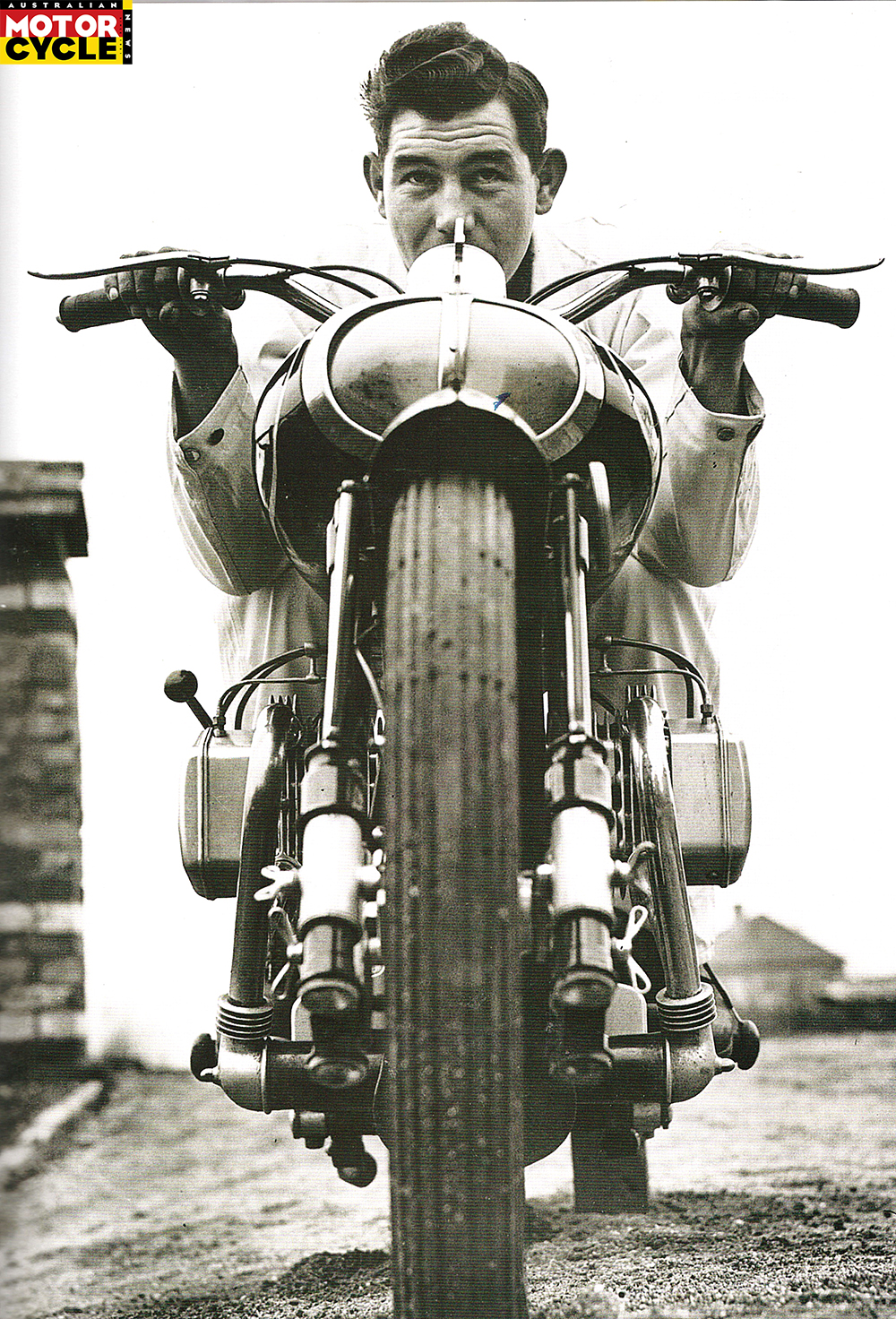

This unorthodox engine was housed in a duplex cradle frame whose lower frame tubes doubled as the exhaust pipes. Undamped plunger suspension was featured at both ends, but this time there were two spring boxes on either side, including the girder-type front fork, making a total of eight altogether. Wooler’s trademark torpedo-shaped fuel tank carried a Lucas headlight blended into its front, complete with the flying silver spanner mascot bearing the company slogan: Accessibility. Just a single double-ended spanner was needed to work on the bike, which together with a screwdriver, was carried in the toolbox cast into the gearbox housing, while a tyre pump was fitted inside a chassis cross-member. Similarly, the seat’s springs were hidden in the vertical frame tubes, while the two legs of the centrestand could be operated independently to act as sidestands.

But the problems in bringing such a novel design to production were many and varied and mentions of the Wooler project became fewer and further between in the press, and it seemed the ambitious project had died a death.

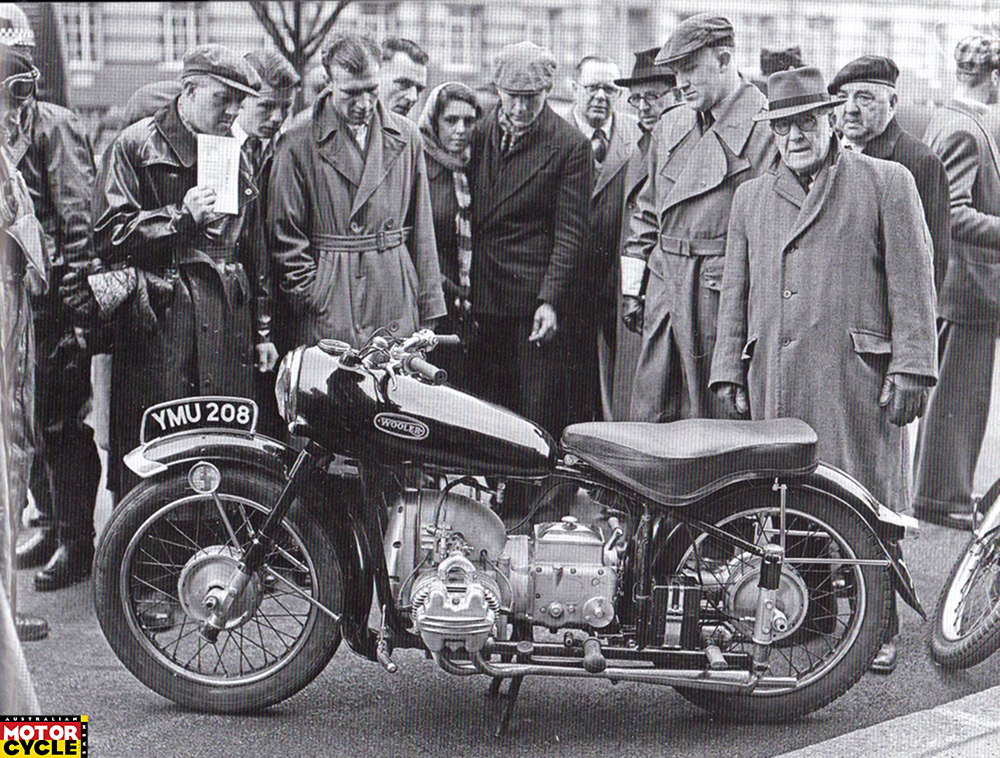

But in October 1952, it was announced the all-new 500cc Flat Four would enter production the following April – and while this ambitious target was missed, it was unveiled to the press in August 1953. In November the following year it was displayed in public to great acclaim at the 1954 Earls Court Show.

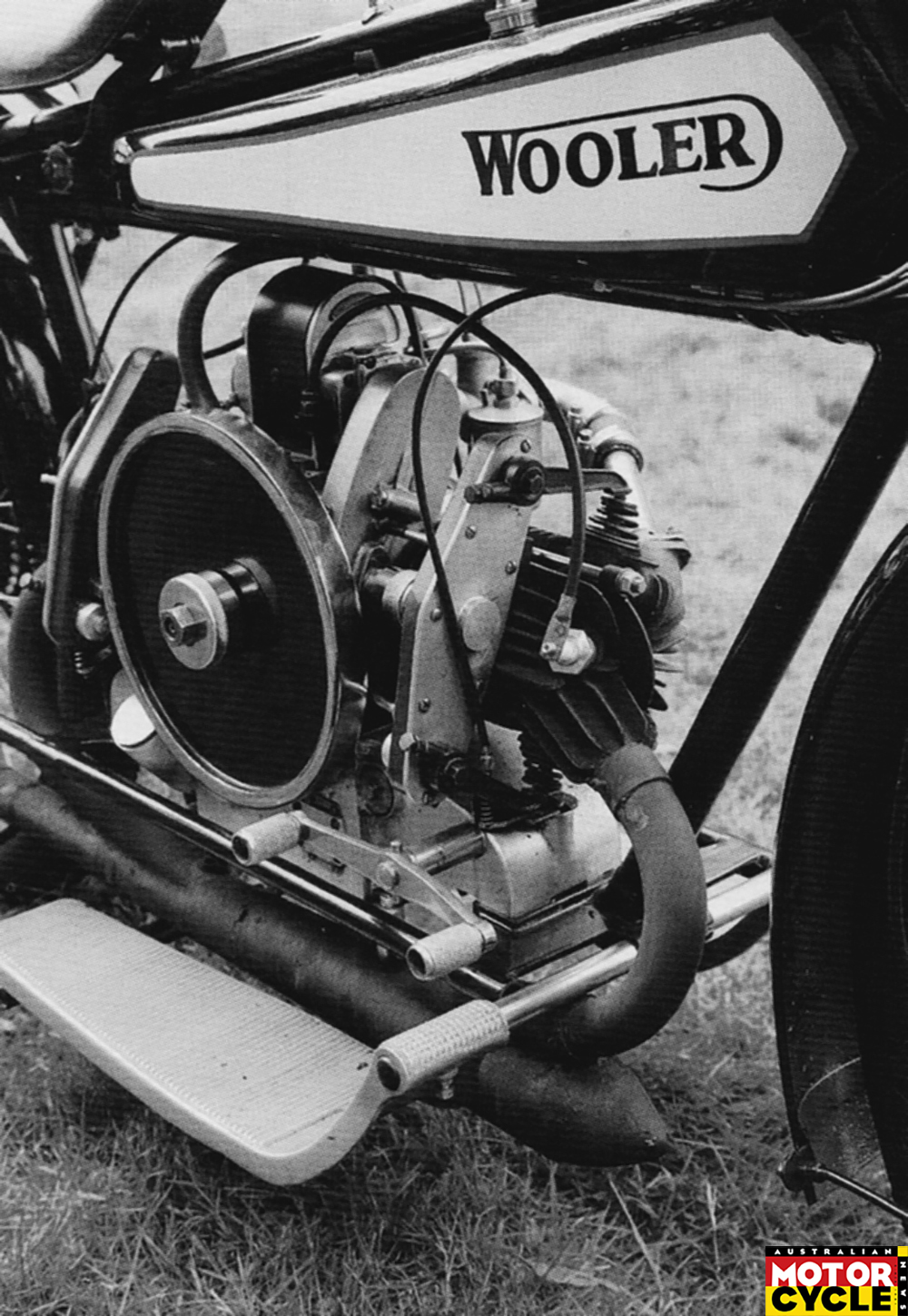

The all-new OHV wet-sump engine had been designed by Ron Wooler, who was evidently more pragmatic than his dad. He’d replaced the beam engine with a more conventional layout, while still a horizontally opposed flat four, the pairs of cast aluminium cylinders on either side each measuring 50 x 63.5mm for a capacity of 499cc were now mounted side by side, rather than stacked, and claimed to produce 32hp at 6000rpm on an 8:1 compression ratio. The forged aluminium conrods had forked plain bearing big ends, while the one-piece cylinder heads each contained two hemispherical combustion chambers. These were operated via aluminium pushrods and forged light-alloy rockers by twin longitudinal camshafts running below the forged three-bearing crankshaft, which were driven by a chain running off the crank.

The same gearbox remained, still with the cast-in toolbox, while the previously unshrouded shaft drive now ran within a swingarm leg. Accessibility was still the watchword, with removal of the engine from the frame claimed to take only 10 minutes using just a single double-ended spanner, with the rear wheel out in three.

This tubular steel duplex frame – now with just a single spring box either side – and a single still undamped plunger spring unit at the end of each leg of a tuning-fork front-end. This delivered a compact 1385mm wheelbase, with a leading-axle mount for the 19-inch front wheel housing a drum brake, all of which was interchangeable with the rear. Dry weight was a claimed 161kg – against 195kg for a concurrent BMW R 50 flat-twin.

This time it seemed the Woolers had struck gold, with press tests confirming the claimed 145km/h top speed. While British dealers were hesitant to commit to orders for a 500cc Flat Four – which at £292 was priced the same as the 1000cc Ariel Square Four – foreign buyers weren’t. After Ron Wooler demonstrated the bike to the Spanish police, he received an order for 500 bikes, while with motorcycle imports banned in Argentina under General Perón, the Woolers had an offer to build the Flat Four there under licence. But with testing going well, their problem was how to gear up to put the bike into production.

Electrical Equipment Co. (EEC), a 50-year old firm building generators initially agreed to handle the machining of engine components, before committing to assembling complete bikes. But the huge number of parts needed, and the large volume required by each supplier to make pricing affordable, cashflow took a hit – and the Woolers hadn’t taken deposits from prospective customers.

But in 1954 Ron Wooler won a government commission to supply a 600cc Flat Twin engine to power a foldaway light aircraft, but then the government cancelled the project, essentially ending the motorcycle project. EEC bailed, and the thousands of components it was holding were sold for scrap – though its project leader Bernard Fowler managed to acquire sufficient parts to build himself a Wooler Flat Four. John Wooler passed away in June 1954, aged 71, without ever seeing the final model bearing his name receive the acclamation it obtained at that year’s Earls Court Show – but he was, however, spared the sadness of its later demise.

Still, in October 1955 Ron Wooler converted both prototype machines to swingarm rear suspension, while the front fork now featured hydraulic damping. But it was too little, too late – even if that year it was displayed on the government-sponsored British stand at the Berlin Trade Fair in Germany. Spurned by all Britain’s mainstream manufacturers, it had the potential to be a range-topping model for any brand. When Ron Wooler passed away in 1980 at just 59, it must have been with lingering frustration.

A total of five Wooler Flat Fours are believed to have been built, two prototypes by the Woolers themselves and three pre-production models by EEC – plus potentially a sixth in Fowler’s own machine. While keeping one for himself, which is now in the UK’s National Motorcycle Museum, Ron Wooler passed the other of the two originals on to family friend Laurie Fenton, and this bike is today displayed in the Hockenheim Museum in Germany, alongside a ‘Flying Banana’ Flat Twin. The only other known survivor is in the Sammy Miller Museum, who found it in the late 1980s and his right-hand man Bob Stanley, restored it.

“It came to us more or less complete but very definitely a non-runner,” said Bob.

“There was no valve gear or anything in the heads, but the bottom half of the engine, pistons inwards, was complete. We sourced the rockers and pushrods from a guy with some Wooler aircraft engines. So we managed to build it up okay, with just the kickstart skew gear mechanism missing, which we managed to adapt from a Sunbeam S8. The rolling chassis already had the swinging arm conversion, so we just had to rebuild the wheels with new bearings and brake linings, fit new seals and gaskets to the driveshaft – and here’s the key!”

Starting the Wooler with a run and bump took me back to my Historic GP days in the late 80s. Even without any choke (the carbs have a cold-start enrichment circuit), the Wooler purred into life almost instantly, though the unique anti-clockwise firing resulted in this Flat Four sounding just like the Miller Museum’s Ariel Square Four I’d been riding only a few weeks previously (AMCN Vol 71 No 01). Riding the Wooler along the almost 2km-long private driveway allowed me to stretch its legs – and it certainly needed the space to do that, because acceleration was frankly disappointing, not helped by a very slow twistgrip action. Considering the low weight, I assume the engine performance was the let-down.

However, persevere long enough and the Wooler does gain momentum, until the needle on the lovely 120mph Smiths Chronometric speedo set into the fuel tank’s headlamp nacelle reaches 65mph at half past six, and it simply stops going any faster. I suspect it’ll cruise at that speed, but I didn’t have the room to find out – but the untuned Silverstone prototype bike was a 100 mph machine, and contemporary road tests speak of greater performance, too. Still, what performance there is, is indeed smoothly delivered.

For a flat-four with a longitudinal crankshaft and shaft final drive the Wooler’s gearchange is excellent, and it doesn’t rise and fall on the suspension when you shift gear as other such twins do. There’s a gear indicator disc on the left flank of the gearbox, which is useful when finding neutral, but it’s dangerous to peer down at this while riding. With a 737mm height for the luxuriously sprung Feridax seat, you’re sitting quite low down but in a comfortably upright stance, with the grips of the one-piece handlebar mounted on the fork stem nicely pulled back. This would be a good long-distance ride, since the jutting-out cylinders don’t intrude on your leg space and the view from the bridge is very distinctive, with the torpedo-shaped fuel tank’s smooth snout stretching away in front of you.

Though I couldn’t test its agility around any tight turns, the Wooler’s handling felt poised at speed, and it tracked very safely through faster sweepers, including one with a bump on the apex. Roadholding was excellent, despite the unusual front-end featuring what’s essentially an oil-damped plunger fork. The brakes, however, simply aren’t effective. But with only two miles on the clock when I took it over – and those entirely registered by riding it up and down the Museum carpark – I suspect the new linings haven’t been bedded in properly. Aside from that, and the lack of acceleration, this was a bike which definitely lived up to the expectations promised by a specification that was extraordinarily advanced for its time.

Before riding the Wooler Flat Four and delving into its background, I’d come to assume that John Wooler had been on a massive ego trip in creating the Light Four and Flat Four. Apart from the fact there are so few photos of him pictured with them that it’s hard to regard him as a self-publicist, the sacrifices he and his son Ron made in swimming against the tide of convention to create these two innovative contributions speak for themselves.

While the beam engine Light Four was certainly flawed, it gave rise to the Flat Four, which by any standards is a two-wheeled work of art. But with no consideration at design stage for cost-effective series production, the problem lay in making its design commercially profitable – and this would surely have entailed making compromises which ultimately neither father nor son would have been prepared to make. What a pity.

SAMMY MILLER MOTORCYCLE MUSEUM

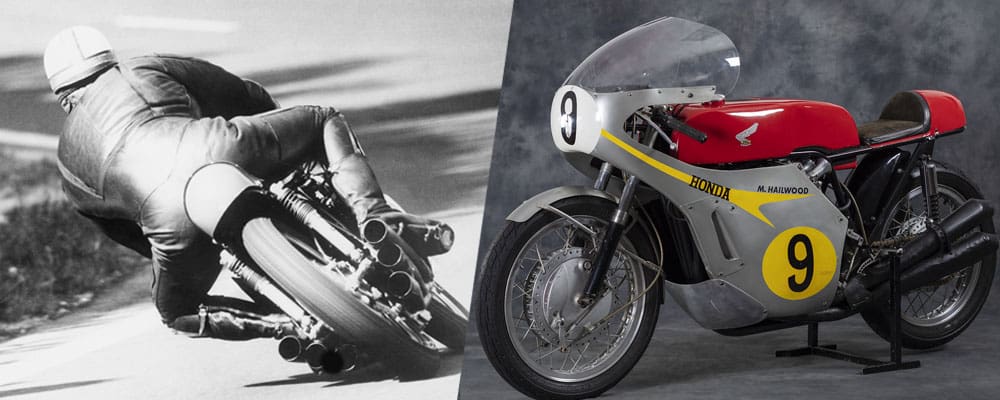

The Sammy Miller Museum in New Milton, Hampshire, UK, is crammed full of interesting machines – including factory prototypes and numerous ingenious designs from all over the world. There’s one of the world’s largest collections of exotic racing bikes, all of them in running order and including the legendary V8 Moto Guzzi 500, supercharged V4 AJS 500 and postwar Porcupine – the first ever 500cc World Champion, V-twin Husqvarna 500, V4 Suzuki 125, 250 Mondial with dustbin fairing, and innumerable famous bikes from Triumph, Norton, AJS, Velocette & many more! And of course, there are plenty of offroad enduro, motocross and trials icons. The Museum is open to visitors daily from 10 am year-round.

The museum address is Sammy Miller Motorcycle Museum Trust, Bashley, New Milton, Hampshire B25 5SZ. Tel 01425 620777/616644 or visit www.sammymiller.co.uk for further details.

Test Alan Cathcart Photography Kel Edge