There’s not much I would rather do after a ride than share time with a bunch of mates around the campfire, drinking, laughing and bantering. This is what our sport is all about – recounting the tribulations, the roads and conditions over a few drinks. And that’s just what we were doing in the BIG4 Wye River caravan park after a successful squirt around the Victorian countryside. Our celebrity chef Paul Mercurio (yes, of Strictly Ballroom fame) was feeding us magnificently with nothing more than a mighty Weber, and we could hear the food sizzling in the background as he poured beer on every dish.

After some dinner and more laughs, our attention turned to our steeds – the reason we were all there in the first place – and the laughing stopped. Every one of the journos at the launch of the Royal Enfield Himalayan was impressed. It’s a bike that offers so much for so little, with the ability to be ridden off road surprisingly well. I remember wondering how they did it, and judging by the silence of the usually rowdy crowd, I wasn’t the only one.

The new Himalayan X1 is a completely new machine from the ground up. The Indian-based and owned company has been working and designing this bike in the background for the past two years to fill a void it always had in its model line-up: the complete lack of a multipurpose machine.

The design brief was to make an ultra-reliable motorcycle capable of being used as a point-to-point workhorse over some of the roughest roads and terrain in the world, something Royal Enfield has achieved through its roadbikes for years. If things did go wrong though, the new machine needed to be simple enough for backyard patch-up work, to keep the country’s population moving.

Yep, you heard me right, the population. In India, where 600,000 Royal Enfields were sold in 2016, virtually none of the current road-oriented offerings enjoy a life of luxurious highway miles. A low seat height and great fuel economy were also going to be essential, as most of these new Himalayans probably wouldn’t be leaving their country of origin.

For these reasons, it made perfect sense for Royal Enfield to produce a simple straight-forward adventure-style motorcycle.

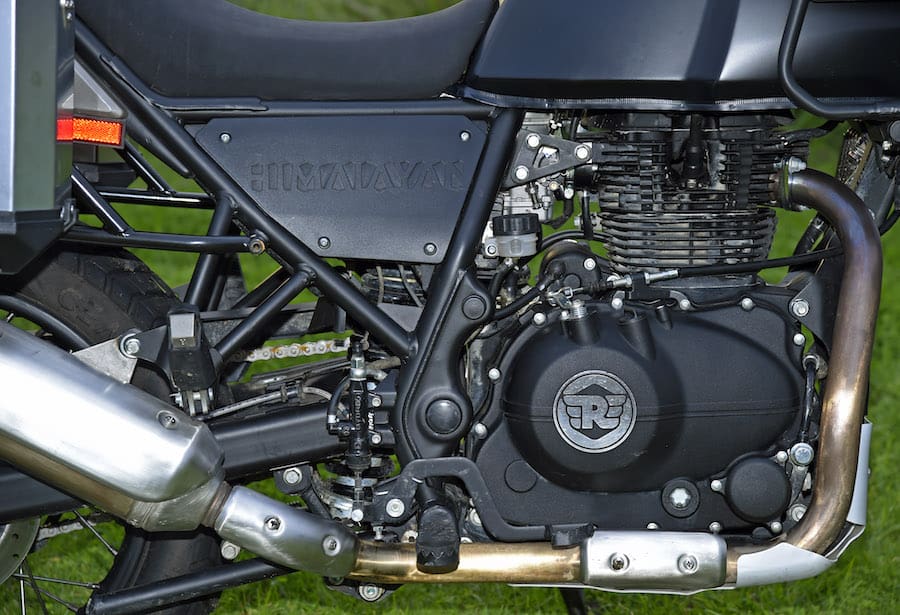

The development of the Himalayan was an immense undertaking, with not only a new frame being designed by Harris Performance in England, but a new engine called the LS410 making its debut. For the first time in the company’s history, Royal Enfield also mounted a linkage-activated rear monoshock system instead of its conventional twin-shock design. The idea was conceived about mid-2013, and by early 2014 there was a test mule running around in England being tweaked by the Harris Performance team to make the basis of the machine in Aussie showrooms today. Harris Performance also designed that monoshock rear end with its linkage ratios, making sure the whole package gelled together using the vast knowledge and experience gained over many years of fettling and racing.

The pedigree is promising, but at first glance the bike did not amaze me. They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and that is true, but aesthetically I would have liked more forethought to have gone into the presentation of the Himalayan. It’s designer, South African Pierre Terblanche, is renowned for futuristic designs like Ducati’s 999 superbike, which would still look cutting edge if it were released today, so perhaps this machine will grow on me. In any case, the effect of the styling on sales figures won’t be huge, because as you get past that initial introduction you realise that this bike has quite a high quality of build.

The switchblocks are top class, and while the instruments are simplistic, they are effective and easy to read. The engine has clean lines and in general the quality of the major components is excellent. I like the attention to detail in a bike that is retailing for $5990 (+ ORC), because those small things are the day-to-day items that make for a better ride experience – and a bike that is easier to live with.

The Aussie Royal Enfield distributor, Urban Moto Imports, told us that the Himalayan model delivered to our shores is the most current version of the Himalayan. I’m guessing though, that they haven’t seen the need to improve the seat – which is a shame, as more padding would have completely changed my first impression of

the bike. However, as it turned out this wasn’t as big an issue as I initially thought. Over the course of the next two days’ riding I became used to the lack of support and my butt was in surprisingly good shape at the end of it.

Putting the seat aside, the rest of the bike is good. There’s a nice reach to the handlebars and the seating position is ergonomically correct. I did notice that the clutch perch has no hand adjuster like most bikes do, which worried me a bit. The only way to adjust the clutch is down on the engine with spanners, but the good news is that the Himalayan comes with more than just a token toolkit – unlike so many bikes. The clutch was certainly strong and I gave it plenty of abuse, but thankfully I never needed to get the tools out.

Starting is not a simple affair like on most modern machines – just tapping a button won’t fire the X1 into life. For the young folk out there, this bike has no EFI, it’s got a thing called a carburettor. Easy to work on in the outback and feasibly more reliable on Mount Everest, but morning starts require turning the fuel tap on, pulling the choke and then tapping the button and remembering to turn that choke off again. It’s no big deal and kind of nice to remember the old ways.

Once the engine is warm the tune is very good, and I doubt anybody could tell the difference between an EFI bike and this old-school carb. The power delivery is smooth with no jerky throttle, allowing you to keep forward momentum without flat spots or splutters.

The first time you pull the front brake lever is pretty interesting, though. I initially thought the bikes were so new that the pads needed to be run in, but that was not the case. It takes quite a bit of lever effort to pull the bike down from speed. Once again, I don’t think that it would be too hard to fix this problem. A set of better quality pads would be at the top of my list if I were to buy one of these bikes.

Freeway cruising is easy, with nothing to take your mind off the road. All the info available is on the dash in real-time to see. There are no heated grips or cruise control like the BMW GS, but you can buy multiple Himalayans for the cost of one GS – or perhaps just buy an aftermarket heated grip kit, and pocket the difference.

There was some conjecture about the screen and its ability to cut a path through the wind. I found I got buffeted no matter where I sat, but a few of the guys on the launch had no issue. I think it comes down to your own preference on this one and with a massive raft of options on the way, I feel there will be a larger screen available soon.

The Himalayan’s non-adjustable suspension is quite compliant and works well with that Harris-designed chassis to give a very good experience when you are just patiently clocking up miles on the freeway. But it’s when you press the indicator button and veer off the beaten track that things get surprising.

I honestly didn’t hold much hope for the Himalayan when I read the spiel in the press conference that this bike would handle the rough stuff, but – gulp – I was wrong.

On paper, it doesn’t have a lot going for it with its non-adjustable 200mm of front suspension and 180mm on the rear, off-road tyres from a company I’d never heard of (CEAT) and a 411cc motorbike that weighs in at over 180kg.

But the bike also has a lot of good stuff going on. Firstly, the suspension both front and rear is surprisingly well mannered in the dirt. I have been doing a lot of adventure riding lately and have been lucky enough to try all the major brands, and this suspension punches above its weight. Normally bikes with a smaller price tag are a disappointment when it comes to riding them. Royal Enfield has genuinely put in some effort to make this set-up work on the road and off it, and has pulled it off quite nicely.

A massive part of the credit should go to the Harris brothers, as it’s the frame they designed that holds the Himalayan together. It’s made of all the right materials and the angles and geometry to make this bike work. As a package it’s a good all-rounder.

There were a few different aspects to the off-road component of our ride, including slippery mud-covered single trails, a few low-level jump sections, and even a bit of sand thrown in for good measure. My favourite – and the one where I thought the Royal Enfield was in its element – was a 20km run up the Wye River to Separation Creek, east of Lorne. It consisted of 50-60km/h corners covered in loose stone, which meant there was a lot of movement under the bike.

The Himalayan was in a constant drift, and had just enough power to get the rear spinning and sliding on turn exit. The bike excelled, and thanks to the work put into the chassis, I felt in control pretty much all the time. Even the front brake I had been worried about worked well in these difficult situations, giving good feel and never locking, even though this machine has no ABS.

Amazingly, those CEAT tyres were quite good. They gave me a decent amount of feel off road in various conditions and only in a very slippery creek bed did I have some nervous moments.

There was also a nice twisty asphalt road heading out from the back of Lorne to Erskine Falls that let me test the scratching ability of those CEAT tyres. The surface was far from perfect, with wet patches, potholes and changing tarmac. But the tyres and bike combo once again handled all that was thrown at it. I managed to scrape the ’pegs and was pushing quite hard with good feedback from the rubber. If I owned the bike though I would fit a better-quality set of tyres at replacement time, and I’d opt for a known brand with history, just as cheap insurance.

After riding the bike for a while off road, a couple of other modifications came to mind. First, the ’pegs tended to have a bit of a droopy feel, especially when the rubber inserts were removed for the off-road section. I would look at aftermarket ’pegs, just to lift the overall quality. My only other gripe was the sidestand. It was always a bit of a struggle to find an area where the bike would balance well when parking. The stand is easy to reach but probably slightly too long, meaning I was in fear of it toppling over. It never did, but I just had that unnerving feeling.

Heading back up the freeway from Geelong after a couple of fun days on the Himalayan gave me some time to reflect on this new model. It’s not perfect by any means, but I don’t know a bike that is. It can’t compete with models like the Triumph Tiger 800, the BMW GS family, or the new KTM Adventure range in a mechanical sense, but it can go to the same places these machines do, and at a fraction of the cost.

Its fun factor is huge, with lots of laughter and hilarity to be had. It’s also LAMS approved – with that low retail price and the ruggedness of a mountain bear, it could be the perfect bike to ride to uni or work during the week, then take off road on weekends. I won’t be surprised if a lot more groups of mates find themselves swapping stories around the campfire after adventures on their Himalayans.

TEST STEVE MARTIN PHOTOGRAPHY JEFF CROW