Why do you want to interview me? I’m just a 53-year-old washed-up grand prix rider with five toes missing,” says Daryl Beattie with a look that’s half-serious and half-joking.

Those who study the racing statistics and form guides think differently. They know that, if not for a couple of controversial career decisions and a devastating string of ‘bad luck’ accidents, Daryl Beattie would have been the rider to seriously challenge Mick Doohan’s unbeatable run of grand prix wins in the mid-1990s.

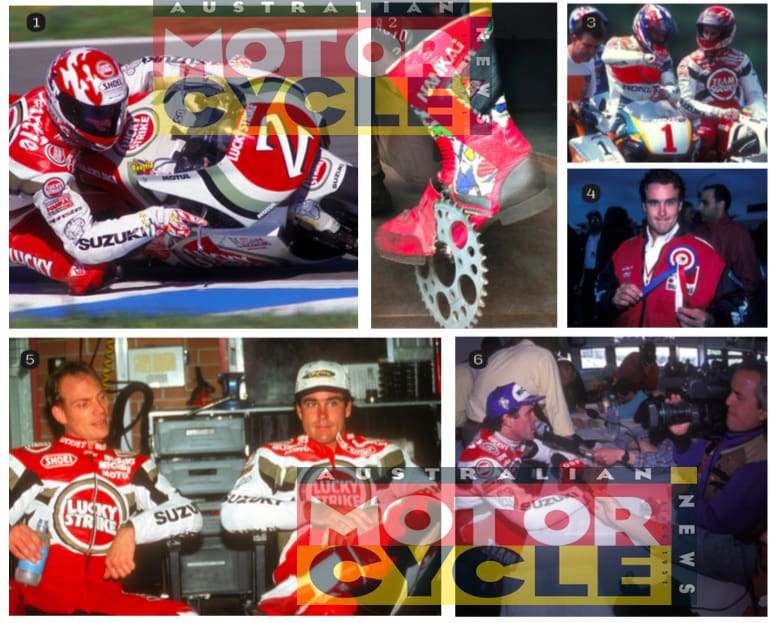

In 1993, his first full championship season, Daryl stepped onto the top of the podium after just six races. He was less than a year older than Casey Stoner was when he won his first grand prix (Stoner, aged 21, went on to win the title that season, his second year in the MotoGP championship). Beattie’s feat of finishing third overall in his rookie full-time season of 500cc racing has only been bettered since by two riders: Valentino Rossi and Marc Márquez.

In his short career, Daryl would go on to achieve three GP wins, seven second places and four thirds.

Sadly, early retirement was forced on Beattie when he was just 27 years old.

Now he’s deep into another phase of his life. When we arrive at his mountain retreat behind the Gold Coast, he’s out working with his father, Paul, loading up an old Hilux ute for a run to the dump. Daryl’s mum, Wendy, is helping prepare for the upcoming outback motorcycle tours and is deep into day one of a month of cooking. Yes, a month. The menu along with notes on cooking, freezing and storing are written up in detail on a whiteboard in the kitchen. Daryl’s self-reliant outback expeditions are built on meticulous planning.

But not only is the DB Adventures outback tour guestbook filling up, the house is about to get a total renovation, and Network Ten’s RPM program is getting ready to roll again. Busy times.

It’s a long way from Daryl’s immediate post-racing years in the late 1990s when he couldn’t even bear to look at a motorcycle – the pain of his enforced retirement was too great. Even now it takes an effort for him to relive his grand prix glory days. But he digs deep into the memories as we spend a day with ‘our Daz’…

Where it all started

Born in 1970 in Charleville, Queensland, Daryl was the youngest of two sisters and a brother.

“Dad worked across the Diamantina country as far as Birdsville, on cattle stations and as a plumber,” Daryl remembers. “I think that’s why I’m so fascinated by the outback now.”

His interest in motorcycling began in an unlikely manner. Nine-year-old Daryl won a Suzuki RM50 on Agro’s cartoon show.

“I was actually presented with it on Channel 7, my first television appearance,” he laughs.

By this time the family was living in outer-suburban Brisbane.

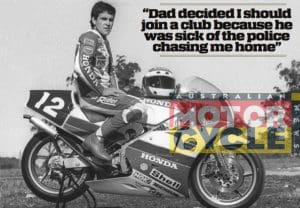

“There was bush near our house and I ended up riding it there until Dad decided I should join a club because he was sick of the police chasing me back home,” says Daryl. “He never had a lot of money but Dad was good with his hands and he built a trailer and we went dirt-track racing.”

From there he progressed to speedway.

“My real ambition was to race speedway in the UK,” Daryl says. “As a 15-year-old I had a two-valve Jawa and was invited to race at Surfers Paradise Speedway. I won the night but it ended in tears when it was discovered I was underage. Next weekend Dad and I went to the Swann Series, saw Wayne Gardner and co and I realised road racing was for me.”

How did a teenager finance it?

“I left school at Year 10 and got a job as a lackey at John Oliver’s Moorooka Yamaha,” he says. “I bought an RZ250LC and my first road race was on my 16th birthday, 26 September 1986, at the last ever meeting at Surfers Paradise Raceway. Back then I was pretty much the only young kid road racing, whereas nowadays it’s run of the mill. I was fortunate enough to be in the era where the international Australian stars came home to race in the domestic series. I think the closest thing to it now is the Spanish domestic championship.”

Daryl was a kid in a hurry, impressing his elders with his raw ability but also level-headed enough to learn from them. He says his biggest influences were Michael Dowson and Jeff Sayle. Sayle was about to transition from racing to team management, while Dowson appeared to be on the verge of entering GP racing after years of success in Australia, Asia and Japan.

Daryl got his first big break through Yamaha.

“Warren Willing and John Cotterill organised a discounted new TZ250 for 1988,” he says. “Mum and Dad worked hard to get it for me and Mike Dowson was a great support.”

Then Honda came knocking for 1989.

“They took me on with an RS250 and I won the Australian 250GP title and was 12th at the Phillip Island World 250cc Grand Prix race (out of 33 finishers),” says Daryl.

He finished a big year by winning the Swan Lager Six Hour at Phillip Island with Malcolm Campbell on a Honda RC30 Superbike.

Back to school

Still only aged 19, Daryl was sent off to a kind of finishing school in Japan, courtesy of Honda.

“My connections with Honda Australia, and especially Mick Smith, got me a test on a GP NSR250 at Suzuka,” he says. “I did a couple of 250cc domestic races in Japan and then got involved with the TTF1-spec RVF endurance racer.”

Jumping from two-strokes to four-strokes would become a pattern for the next two years.

In 1990 Daryl won the biggest race of his career so far, the Suzuka 200km, a lead-up to the 8 Hours but with only one rider and one fuel stop.

“It was a pretty cool race to win,” says Daryl, “being a lot more laps than a GP.”

He also came fourth in the 250cc world championship round at Phillip Island. Later that year he finished fourth in leg one of the final round of World Superbikes at Manfeild, NZ.

He then won the major races at Australia’s richest meeting, the Arai Cup at Eastern Creek,

on an RC30.

“If you won everything you got over $30,000,” he says. “I won both legs of the main event against guys like Malcolm Campbell, Peter Goddard and Rob Phillis, but I crashed out of the Dash for Cash.”

Most of 1991 was spent in Japan racing either the RVF four-stroke or 500cc two-stroke in the Japanese championships.

“I learned about Japanese food and culture, and how different it is over there to Australia,” he says.

Mum Wendy chips in: “I used to cry on the way home from dropping you off at the airport. You were still young and I didn’t know if you had any idea of how you were going to get from the airport to the factory. They left you to find your own way but I guess they were trying to toughen you up.”

Daryl explains his involvement with Honda’s racing development program.

“At that time Honda was turning its RVF endurance and TT racer into the RC45 [successor to the RC30 Superbike – see feature on page 68],” he says. “I was testing it as well as racing in the Japanese TTF1 championship. We brought a prototype RC45 out to the 1992 pre-season 500cc test at Phillip Island and I did ‘thirty-sixes’ on it.” The Superbike lap record of 1m38s had been set a few months earlier by Kawasaki factory racer Aaron Slight. Daryl was also testing new ideas for Honda’s 500cc GP effort.

“The factory had a secret proving facility and I did a lot of wind-tunnel testing,” he says. “I also did midweek tests on a go-kart track testing fuel-injection systems on two-strokes.”

“The engineers actually built a completely new engine, castings and everything, that I tested but it never saw the light of day,” he reveals. “It was a twin-crank NSR500 very much like the Yamaha design of the time. Looking back I reckon I was the only round-eye that I knew of working in that part of Honda’s operation.”

Injury to Wayne Gardner prompted Honda to take a chance with Daryl and he made his 500cc GP race debut at Eastern Creek in 1992. He finished third and backed it up with a sixth at the next round in Malaysia.

Later that year, he teamed sensationally with Gardner to win the Suzuka 8 Hours (Gardner had won it the year before with Mick Doohan).

“I remember being surprised at how the RVF had lost a few ponies being turned from TT-F1-spec into an 8 Hours bike,” he says.

Nevertheless, press reports of the time described the winning RVF as weighing less than 140kg, about 10kg lighter than even Ducati 888 Superbikes of the time, and producing around 115kW. Reports also described Beattie as being groomed as Gardner’s successor. And so it came to be – Beattie’s win in the All-Japan 500cc title later that year plus Gardner’s career retirement saw him become Mick Doohan’s teammate for 1993.

GP tearaway

Young Daryl wasn’t overawed by the big time.

“I’d raced against many of the big names at the Suzuka 8 Hours and in the All-Japan 500cc championship so I knew what to expect,” he says.

He built his championship momentum quickly, achieving his maiden win at Hockenheim in Germany. Doohan led that race early but retired with a mechanical problem. Kevin Schwantz then took the lead with Beattie second. Then, on the last lap, Beattie pounced for the win. An indication of both the race pace and Honda’s technology was third-placed Shinichi Itoh setting the first 200mph (321.86 km/h) top speed in 500cc GP racing. Itoh was the third rider in Honda’s team and had a development role, even using fuel injection for several races that year.

Honda’s 1993 pay cheque for Daryl was $400,000 (worth nearly $1m in today’s terms). Soon he would join GP’s earning elite thanks to a multi-million-dollar deal with Yamaha.

Leaving Honda

Daryl finished 1993 third in the championship with a win and three other podiums, but already was on the way out of Honda

“They were releasing the RC45, told me it ‘had to win’ and wanted me to race it in World Superbikes,” Daryl said. “Superbikes was not where I wanted to be.”

Cashed-up Team Roberts Marlboro Yamaha snapped up Beattie to replace Wayne Rainey and he joined Luca Cadalora, but it was not the move he had hoped for.

“It was a disaster for me, both the bike and the [Dunlop] tyres,” he remembers. “In testing

everyone privately agreed that the all-new 1994 bike wasn’t great, but we all wanted to make it work. They literally pulled out Wayne Rainey’s old bike on the eve of the first round and fitted the new parts to it.”

The turning point was at Le Mans, France.

“I lost five toes in that crash when I landed back on the bike after a highside. The end of my boot was hanging off and white bones were sticking out. A flag marshal fainted. Years later I found out that the tyre warmers hadn’t been turned on.”

Daryl returned to the paddock six weeks later, despite his foot still bleeding, but his first race back was another disaster.

“I was battling at Laguna Seca with Norick Abe [his replacement during his recuperation] when the battery running the power valves died.”

Cadalora went on to win the race and cement second in the championship behind Mick Doohan while Daryl walked away to Suzuki.

“Kevin Schwantz got me to Suzuki and Gary Taylor did the deal,” he says. “Straight away I felt comfortable on the Suzuki, its Kayaba suspension and the Michelin tyres.”

Hangin’ five in ’95

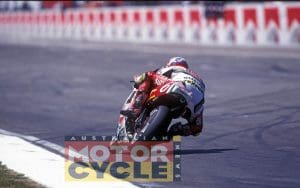

Daryl was the only rider to seriously challenge a dominant Mick Doohan in 1995. In 1994 Doohan won the title by 143 points from Cadalora. In 1995 Beattie finished just 33 points behind.

He took two wins, which he describes as feeling almost effortless.

“I especially remember Nürburgring [Daryl’s last win]. I qualified well, then Mick Doohan crashed in front of me and I finished nearly 10 seconds ahead of Luca Cadalora. I felt so relaxed I could have gone out and done another race.”

Daryl’s win at Japan earlier that year was also a significant victory, even though he was on a Suzuki, not a Honda.

“It felt like a homecoming because I had won the 8 Hours there,” he says. “By the middle of the year I was convinced I could win the championship.”

Daryl was leading by more than 20 points and then broke his collarbone during practice at Assen. He got it plated and returned to finish third in the next round at Le Mans.

“The title fight went right down to the [penultimate] round in Argentina and we both broke the track lap record,” Daryl remembers.

Doohan won the GP and the world title but Daryl set the fastest lap.

“I was really excited about the 1996 season and early pre-season testing looked promising with the Suzuki faster over a race simulation distance,” Daryl says. “Then they went looking for more mumbo and started playing with the pistons.”

The result was a series of piston seizures and massive highsides that knocked Daryl out.

“When you shut off from full throttle the tops would tear off the pistons. When it lunched itself in Malaysia I was in intensive care for a few days. It happened twice in a row back in testing in Europe so I had three concussions in a row.”

Teammate Scott Russell was racing a lower-spec engine and went on to finish sixth in the championship while Daryl languished in 18th. A fourth place at Mugello, Italy, was followed by a qualifying highside at Paul Ricard, France.

“It was my fault,” says Daryl. “I got flicked over the top on the cold side of the tyre.”

As well as being knocked out, he had a collapsed lung and broken wrist.

“I don’t remember going home to Monaco,” Daryl says. “After an X-ray showed I had a fractured skull a neurosurgeon told me: ‘Go home and let it heal’.”

But at the start of 1997 he says “everything felt weird” and he struggled. Medical tests in Europe couldn’t pin down Daryl’s troubles and it took an Ears Nose and Throat specialist in Brisbane to discover a ruptured eardrum.

“I didn’t have any speed and didn’t know why,” he says of 1997. “I tried as hard as I could but ended up just not wanting to be there anymore.”

Matters came to a head as the season neared its conclusion.

“Suzuki weren’t talking to me about 1998 and when I turned up at Phillip Island [the last round], I was also sick with the flu so went home,” he says.

Honda offered a lifeline with a ride on the new twin-cylinder NSR500V. He turned it down and it went to Sete Gibernau.

It was a sad end to what had promised to be a stellar grand prix career just 18 months before. But Daryl had seen a similar outcome when he first joined Suzuki.

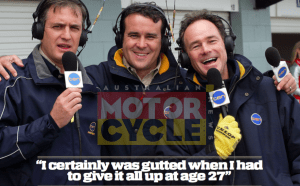

“I was sharing a house with Kevin Schwantz in Austin, Texas,” he says. “One day he said he wasn’t flying back to Europe. I think Kevin’s comment ‘I reach into my pockets and there’s nothing there’ sums up the feeling of many racers realising they have to retire. I certainly was gutted when I had to give it all up at age 27. I didn’t even look at a motorcycle for a few years.”

The long road back

Daryl eventually got rid of “a weird floating feeling” associated with his concussions but says what followed was “two years of nothing”.

“You became a beach bum,” his mother suggests.

“I tried travelling,” he says, and explains by going outside to a couple of old VW Kombis. He jumps into a split-window ute, which looks like a beater but is a real survivor in full working order.

“I drove this to Perth and back through the Red Centre,” he says.

He was still at a loose end when, in 1999, his old schoolmate-turned-sports commentator Leigh Diffey suggested he buy an airline ticket and meet him at the Phillip Island GP.

“The Channel 10 guys got me to describe some on-board footage and the producer came in later and said he’d never heard a lap of the circuit described like that and offered me a job,” says Daryl. “I’d cringe if I had to see some of my early pitlane work but that was where I learned the most about interviewing.”

More recently he started up DB Adventures.

“In many ways Honda’s been my family since 1989 and they helped me out with bikes to start up the tours,” he says. “I reckon they thought I’d only last a year or so.”

Daryl now takes customers across the outer reaches of the outback, including the remote, 1800km Canning Stock Route.

“I can’t get enough of the outback,” he says.

The campside camaraderie, the horizon-stretching emptiness, the self-reliance a traveller out there needs. This world is a million miles away from the goldfish-bowl world of grand prix motorcycle racing. And Daryl couldn’t be happier in it.

By Hamish Cooper

Photography Lou Martin