There’s always a frisson when a new manufacturer dives headlong into the top level of racing. Will they make it? Or will the waters be too deep?

More of a frisson still when they eschew conventional racing practice to embrace novelty. After all, what succeeds in racing is what succeeded last year, plus a couple of per cent. The same mantra on which the Japanese bike industry achieved its strength: copy, but improve.

So when, for example, Aprilia greeted the new four-stroke era with a unique and sonorous in-line triple designed by racing-car firm Cosworth, it was not so great a surprise that it was ultimately found wanting. (Honda’s successful V5 was also unconventional, but based around familiar V4 motorcycle technology.)

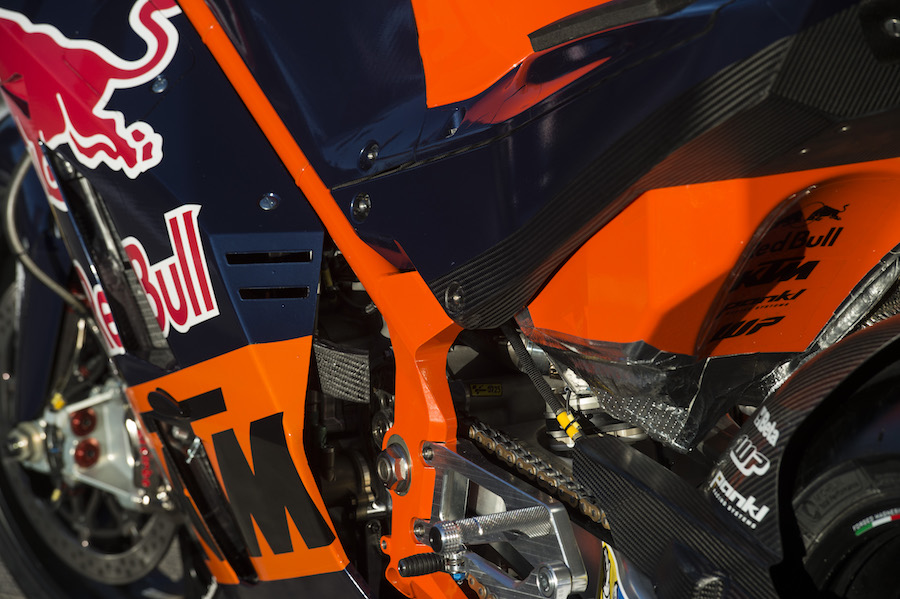

Now it’s KTM’s turn. And while its V4 engine is in line with main rival Honda’s (although the vee angle and firing intervals remain a closely guarded secret), the Austrians have been unable to stop themselves with the same heresy that has marked their participation in the less demanding technical enclaves of the smaller classes.

This time they are using that old and long since outdated chassis construction – welded steel tubes.

But is it really outdated?

If you look back at history, yes. And if you look at the history of heretical chassis designs, ditto. Just remember what happened to those extraordinary French Elf heretics.

Steel tubes were superseded in the 1980s, when extruded complex-section aluminium tubes came into fashion, with fabricated box-section aluminium a viable alternative.

There were several missed cues and false turnings, and it later transpired that the Holy Grail of the time was itself a false idol.

Everyone thought that a chassis should be completely stiff. This would preserve the carefully designed chassis geometry, and allow the suspension to work accurately.

To this end, there had been some earlier experiments in carbon-fibre, most notably by Suzuki’s by-then independent Britain-based near-factory team, battling to find ways to keep their obsolescent square-four RG500 engine competitive.

Racing car designer Nigel Leaper introduced a material then popular on four wheels (and still in commercial aircraft) for its combination of light weight and tremendous stiffness, especially when correctly braced: synthetic honeycomb sandwich board. Not for nothing was the resultant glued-and-bonded chassis nicknamed ‘the cardboard box’. It was very stiff indeed. And very hard to ride.

Over the next few years, metal chassis that on paper failed the ultimate stiffness test actually turned out to be more effective on the track. The truth filtered into general consciousness: extreme stiffness may be correct for a car, but it is wrong for a motorbike. What a single-track vehicle needs, especially with the ever more acute angles of lean achieved on fast-improving tyres, was to be able to flex. But only in the right way.

Controlled flex has been the new Holy Grail for well over 10 years, and remains so. And greater understanding of the design of aluminium spars continues to pay dividends in taming chatter and increasing corner speeds.

However, there’s no technical reason why steel cannot be engineered to give similar results. At least that’s what KTM thinks.

And, funnily enough, what Ducati thought when they entered MotoGP with a steel trellis frame in 2003. I’ve never forgotten the elegant response from Claudio Domenicali, then head of Ducati Corse and now CEO, when I asked him if he thought a steel trellis was the right idea. “That,” he replied, “is like asking your host if the wine is good.”

Well, it was fairly good, but by the time genius rider Casey Stoner won the title in 2007, the steel tubes were merely a vestige, and Ducati had embarked on an affair with super-stiff carbon-fibre that almost cost Rossi his career, and from which they are only now recovering.

We wait to see how good Austria’s wine will be.

By Michael Scott