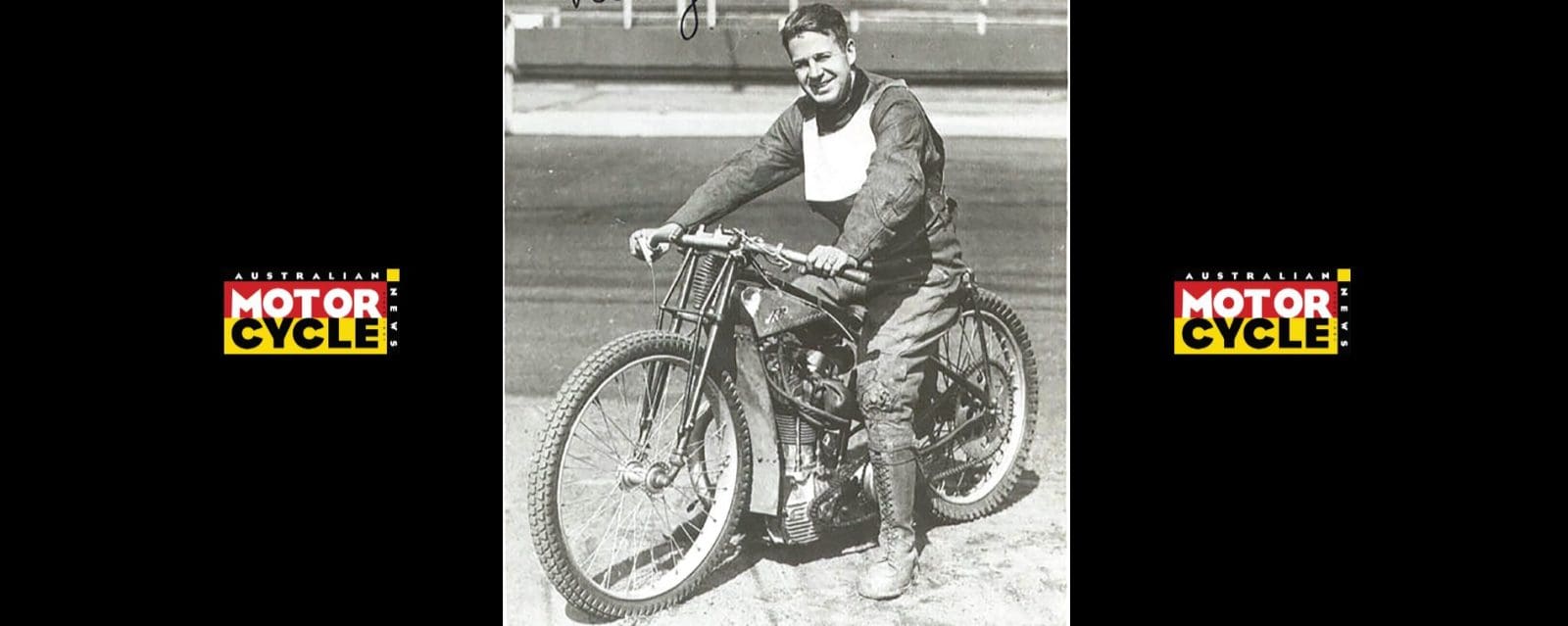

Sixty years ago this Easter, Bob Mitchell won the sidecar race at Mount Panorama on a Norton 500, becoming the only man to win the unlimited three-wheel event there on a single-cylinder machine.

After the race, Mitchell sold the outfit to fellow Victorian Bernie Mack and retired from racing to concentrate on his business career. He wasn’t yet 26, but he had raced on the Continental Circus for three seasons and achieved a placing in the FIM Sidecar World Championship (fourth in 1956) that has never been matched by another Australian. He finished third in the 1955 Dutch TT and 1956 Belgian Grand Prix, and fourth at both the Isle of Man and Assen in 1956.

On the local scene, Robert Lindsay Mitchell (born in Violet Town in October 1931) won Australian TTs at Little River (1952) and Longford (1953) before going overseas. He had previously been the Victorian motorcycle apprentice mechanic of the year.

After returning from Europe, Mitchell won the 1956 Australian TT at Mildura and the 1957 Australian GP at Bandiana. He was a Bathurst winner in 1953 and 1957.

Mitchell was so successful in the 15 months after returning from Europe that, rather than admiring his incredible skill, some on-track rivals and letter writers to motorcycle publications complained about his dominance!

One victory at Mt Druitt was referred to as a riding lesson.

Mitchell with his self-built and tuned Manx Norton, running on petrol, beat 1000cc Vincents running on alcohol.

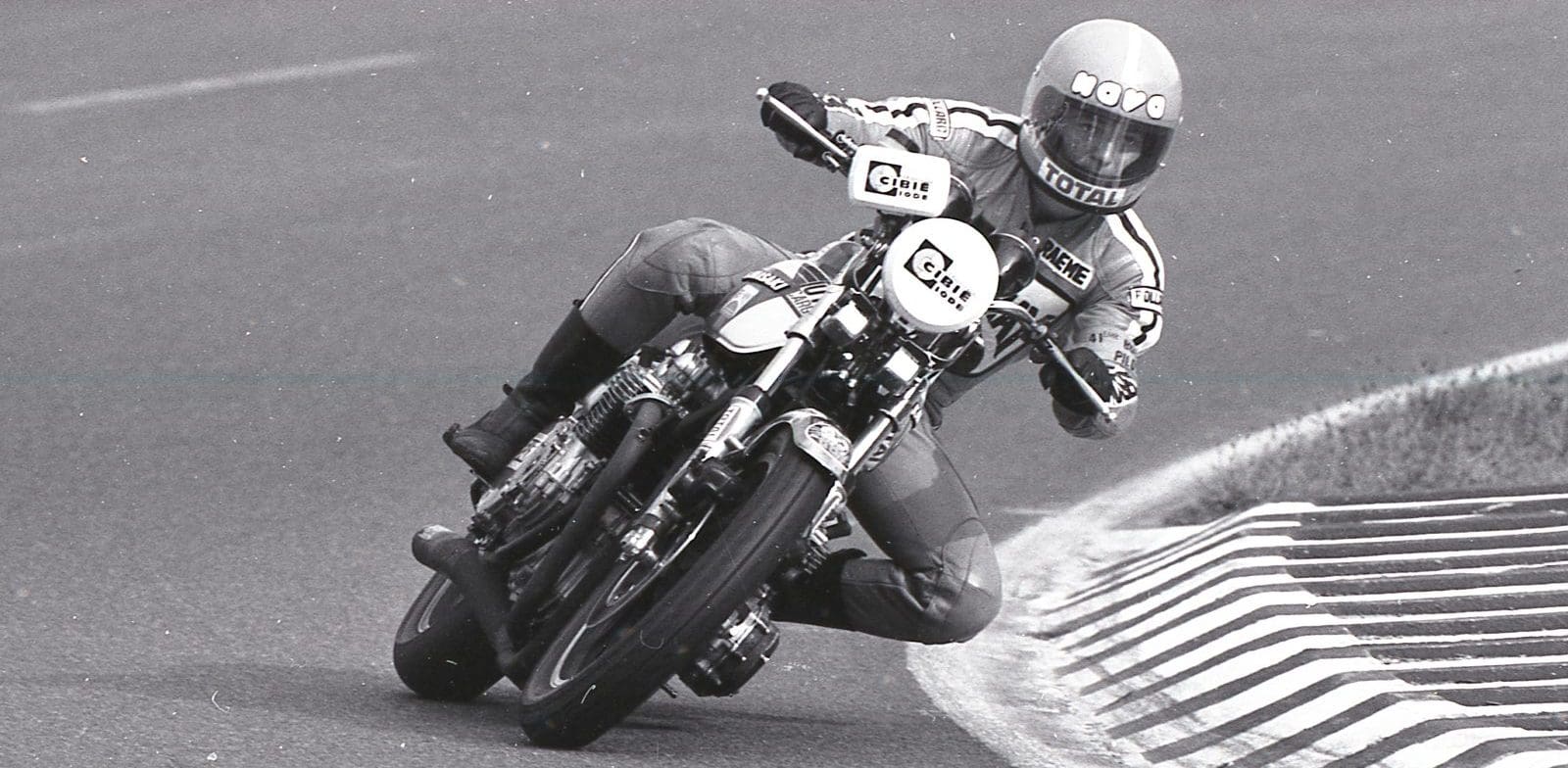

And then there was his style. He was the Sultan of Slide decades before Garry McCoy came along. Power-slide a machine with just 36kW? You betcha. Narrow, rock-hard 1950s tyres didn’t need masses of power to break traction.

One of Mitchell’s friends, the late Ray Kelly, saw many of these races from the sidecar platform of rival Bernie Mack’s outfit. His opinion of Mitchell’s status? “Bob Mitchell was better than they said he was! No one could touch him when he came back from Europe, not even the guys with Vincent-HRDs. He had finished fourth in the world championship and certainly proved himself because there was some hard opposition over there. He came back and broke records everywhere.”

Bob Mitchell was 22 when he and passenger Max George left Melbourne in 1954 on a dilapidated ocean liner. They rode two seasons together before George came home.

In 1956 Bob had hoped to have motorcycle racing reporter Mick Woollett as his passenger, but Woollett was already committed, so British sidecar ace Eric Oliver recommended chirpy Londoner Eric Bliss.

By that stage Mitchell had married Jean, who had been a secretary at Norton Motors, and they had a son, Mark.

When they settled in Australia, Bob had a car dealership in Shepparton, followed by a caravan park at Surfers Paradise and then a tourist boat on the Gold Coast canals. He rode a pristine drum-brake Kawasaki Mach III 500 and bought parts at Bob Cowley’s Gold Coast Motorcycle Wreckers.

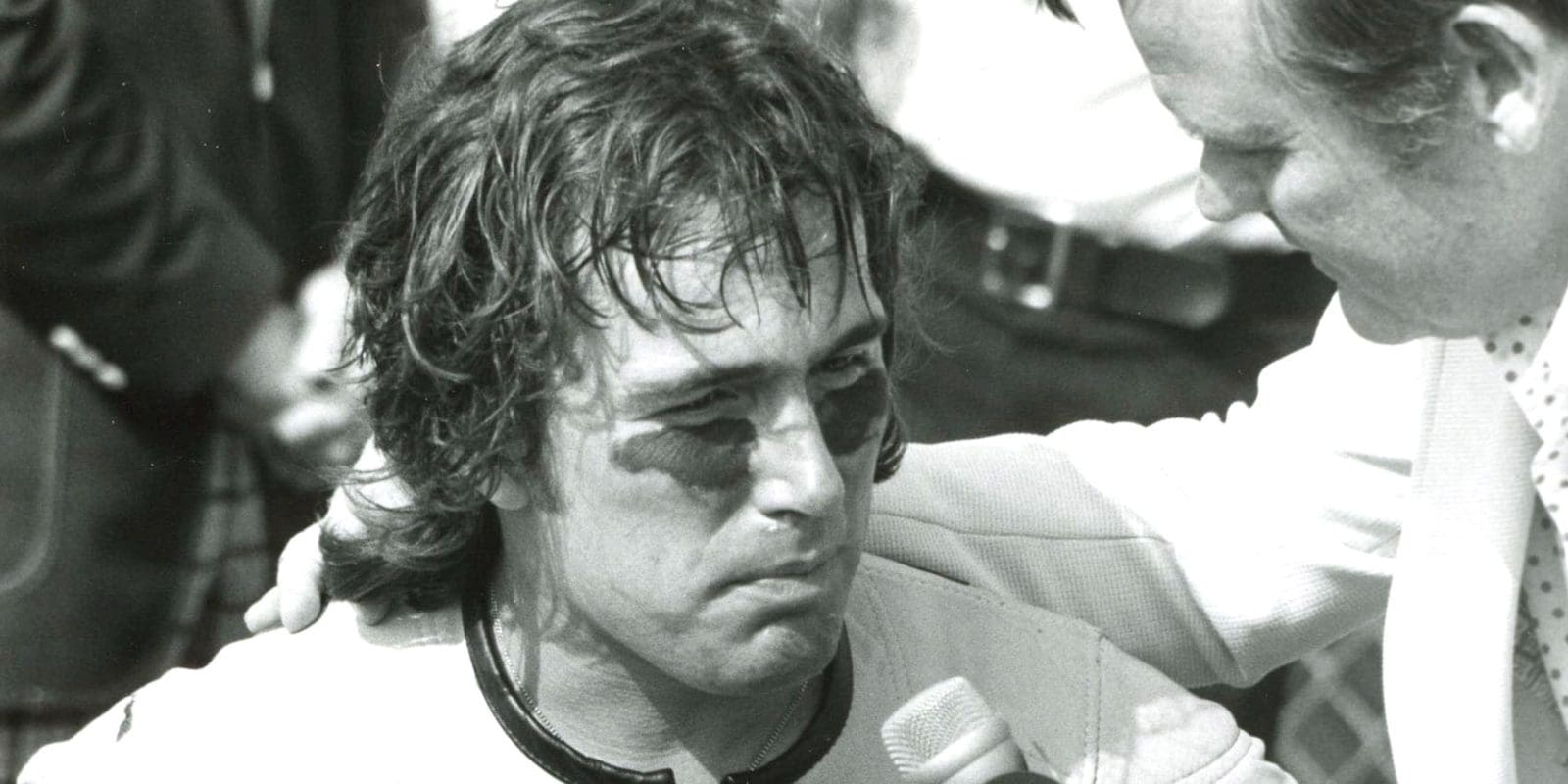

Outside of his family and a couple of friends, Mitchell’s exploits went largely untold for 30 years after he retired. Clearly it was a great story, full of bravery, high drama, gritty determination, romance, tragic loss, elation, disappointment and acts of bastardry. And eventually it did come out, with Bob adding more layers and background right up to his last days in 2007.

Along with the life and times on the Continental Circus came a full picture of Mitchell: feisty, outspoken, sentimental about his lost mates, especially Keith Campbell, and full of classic terms like “not worth a cracker”. Oh yes, and as competitive in his day as any current racer.

Mitchell’s regular sounding boards were his son, and fellow Continental Circus private entrant Jack Ahearn – in conversations laced with sometimes hilarious, often caustic, unflattering and possibly libellous assessments

of various promoters, motorcycle factory officials and team managers.

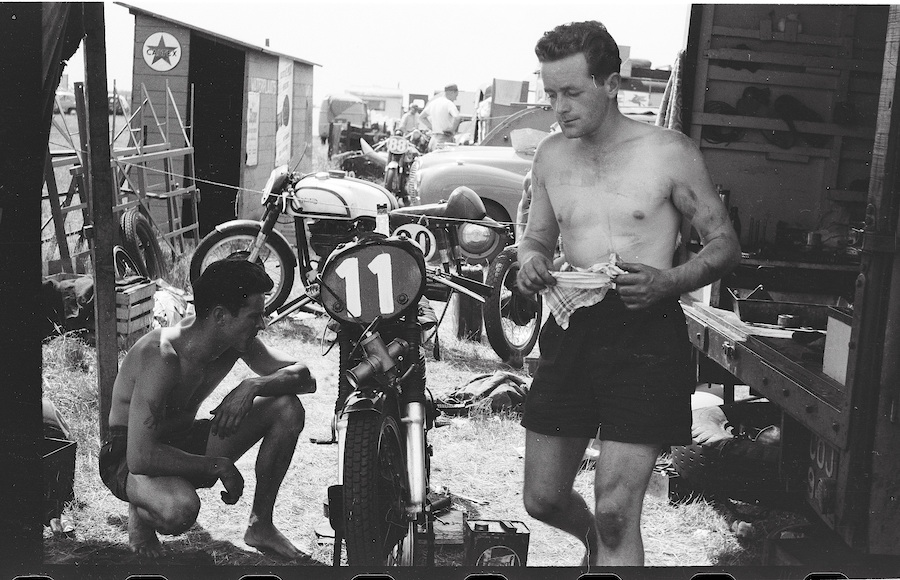

That wasn’t to say Bob did not have a ball. There are photographs in which he can be seen horsing around with fellow racers and their helpers in race circuit paddocks.

But Bob Mitchell was different. Some Australasian internationals in the 1950s were happy just to be able to race every weekend for five or six months. Others were content to have a one-year extended honeymoon in Europe and then settle back home, having lost friends to accidents on public road circuits. Bob was there for only one thing: to win. When he couldn’t get his hands on the machinery required – and in the 1950s that meant a BMW – he sought new challenges.

Bob’s tale is told in The Sultan of Slide – a privateer’s story by his son Mark.

BY DON COX