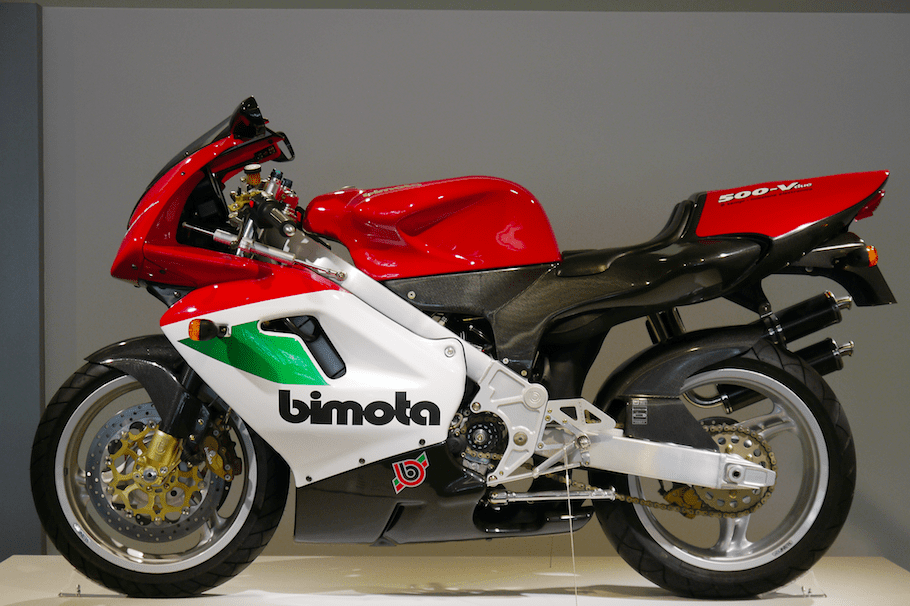

Fewer than five hundred Bimota 500 V-Due two-strokes emerged from the Rimini firm’s tiny factory, and the bike has gone down in history as a spectacular disaster. Hyped as the saviour of the two-stroke, it instead became the final nail in the coffin for two-banger sportsbikes.

Revealed in late 1996, the V-Due (Italian for V-Twin) was arguably the most talked-about bike of 1997 while its development continued, with the promise that production models would reach dealers in 1998. It was heralded as the second coming of the two-stroke; a lightweight, flickable machine with close to GP-bike power and weight, yet with the capability of beating the tightening emissions laws that had already wiped the vast majority of strokers from production.

Of course, we all know now that the dream became a nightmare. That revolutionary engine’s fuel injection system – the key that should have unlocked the door to beating emissions limits and breathed new life into two-strokes – never worked properly. No sooner had deliveries started than customers aired their disappointment in machines that were unreliable, and barely rideable even when they did work.

Eventually Bimota was forced to accept that the V-Due wasn’t fixable and offered to replace customers’ bikes with SB6R or SB8R models, a move that quickly sent the firm into bankruptcy with a warehouse full of glorious, beautiful, unworkable two-strokes.

Yet it could all have been so different.

The V-Due project might have come to prominence in 1996, but its roots go back much further. In the late 1980s, Bimota – which despite its small size had seen considerable racing success at both national and international level with its combination of bought-in engines and bespoke frames – wanted to go GP racing. At the time, the 500cc world championship was made up almost entirely of four-cylinder two-strokes, as it had been for years, but there was a growing idea that twins, benefitting from a lower minimum weight limit of just 105kg against 130kg for four-cylinder bikes, could be competitive.

Later, in the mid-1990s, Aprilia would go on to race twins – effectively big-bore versions of its 250 GP racers – and even Honda developed a V-twin stroker, the NSR500V, on the off chance that the layout would be better than its normal V4 racers,

so Bimota’s idea was hardly crazy.

But it was incredibly ambitious. While Bimota’s ability with frames was beyond doubt, it needed an engine to go GP racing. So it turned to two-stroke specialists TAU Motori, headed by Aroldo Trivelli, to develop an engine for the project.

While that was underway, Bimota chassis guru and engineering chief Pierluigi Marconi was developing a frame for the engine to sit in.

Those familiar with the production V-Due might be surprised that the original idea was to use a Tesi-style chassis with hub-centre steering. In fact it was in this form, variously known as the Tesi 500 or BB500 (‘BB’for Bimota engine, Bimota chassis, just as other models had been called SB, HB, YB, KB or DB depending on their engine suppliers), that the bike first appeared. Intended for grands prix, the Tesi 500 only managed to race in the Italian championship in 1993.

It was at this stage that the racing project was suspended and the company turned its eyes to creating a road-going two-stroke using the new engine as its basis.

However, making a GP bike is simplicity itself compared to building a production model that needs to be produced to a budget and to meet the

wide array of international rules and regulations to be allowed to go on sale.

While the first road-going prototype continued the Tesi-framed theme, Bimota at this stage was moving away from hub-centre steering and back towards more conventional aluminium frames. Marconi developed a lightweight oval-tubed aluminium trellis that used the engine as a stressed member to help keep weight down, and the whole lot was wrapped in carbon-fibre bodywork designed by Sergio Robbiano. Although many period tests claimed that the V-Due’s weight was as low as 145kg, official technical documents put it at 164kg dry, or 184kg with everything needed to run, including a tank of fuel.

The big challenge, though, remained getting the engine to pass emissions limits that were rapidly killing two-strokes across the board. Bimota decided that the solution was fuel injection.

While injected two-strokes weren’t a totally new idea – Honda had even run its NSR500 GP bikes with injection in 1993 before reverting to carbs – Bimota’s method hadn’t been tried before. Where previous efforts had simply replaced carbs with throttle-body injection, Bimota struck upon the idea of direct fuel injection as the solution.

Instead of mixing the fuel and oil with air before it was sucked into the crankcase, fresh air alone was drawn in. Just like a normal two-stroke, that air was then transferred to the cylinder above the piston, forcing out the exhaust gasses, but because there was no fuel mixed in, it was no problem if some of it went straight out the exhaust. Only after the piston had risen enough to close the intake and exhaust ports was the fuel added – squirted straight into the combustion chamber.

Bimota wasn’t the only firm working on direct injection for two-strokes in the early 90s. Australian company Orbital was pushing its own direct-injected stroker design and getting a lot of interest from car firms. Surprisingly, the engines were reckoned to be more efficient and environmentally friendly than four-strokes.

But direct-injected strokers had a big problem to overcome. To be emissions-friendly they couldn’t add fuel to the mixture until the very last moment, after the exhaust port had closed, and that left very little time for the fuel to atomise and mix with the air in the combustion chamber.

While Orbital’s successful solution was to use high-pressure compressed air to atomise the fuel as it was injected, Bimota reckoned that if the fuel was fired from the injector and bounced off the top of the approaching piston before the spark plug fired, it would be atomised enough to burn. With this system in place, Bimota arranged for Motori Franco Morini to produce the engines on its behalf and forged ahead with development and production of the V-Due.

Unfortunately, the direct fuel injection that was intended to make the V-Due a viable roadbike and guarantee Bimota’s future instead proved to be a costly dead end.

The bikes were often reported to be spectacular by journalists who were given closely supervised test rides on hand-made, carefully set up pre-production bikes with Bimota technicians close by to keep them in perfect tune. But customers with production-spec bikes soon discovered that they just didn’t work. They would misfire, oil their plugs, drop onto one cylinder at random moments, or seize entirely. It left owners and the factory alike bemused, with varying symptoms from one bike to the next and no clear solution.

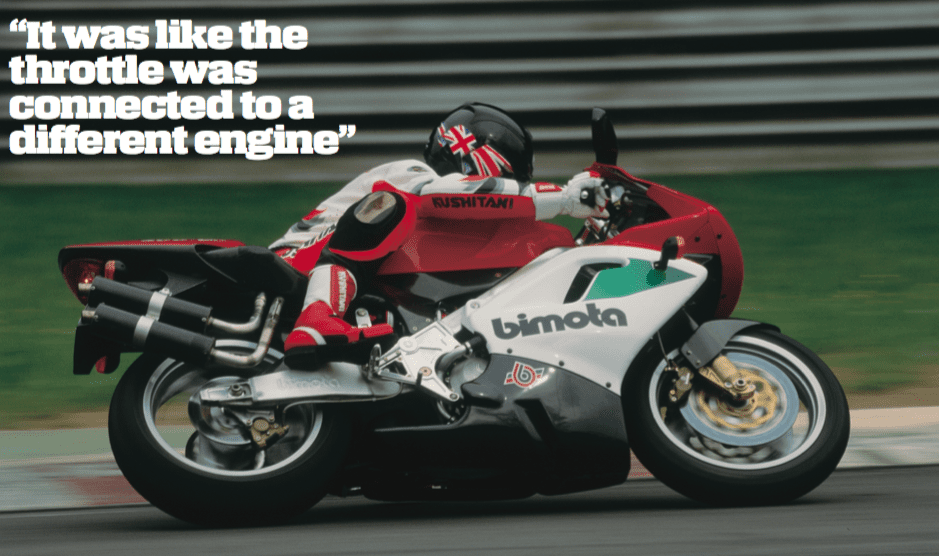

Chris Moss is a British bike journalist who got to experience a customer-spec V-Due when the bike was new. It’s not something he’s forgotten, even almost 20 years on.

“It was fantastic on paper, but the bike just didn’t work,” he says. “The throttle response was awful. It was like the throttle was connected to a different engine; just unrideable. It wasn’t ready for sale.”

Some said the problem was the fuel injection – that using the piston as a surface to spray against didn’t give a predictable result. Sometimes the fuel would be atomised and burn properly,other times not. The engines tended to work properly only in a very limited rev range – some said the spread was 1500rpm, the less charitable put it at nearer 500rpm – when the piston and fuel came together at just the right speed. At other speeds, getting the fuel to burn was a hit-and-miss affair, with plugs soon fouling and making performance worse still.

Other theories ranged from ignition problems to incorrect port heights.

Regardless of the cause, the issues weren’t fixed and owners were soon demanding refunds.

Despite order books that suggested Bimota would be turning out 500 units per year – a huge number for the tiny firm, particularly given the high price of the bike – in fact only 185 of the original, fuel-injected V-Dues were produced. Bimota withdrew the bike from sale and bought back many of them, offering owners replacement models from its range.

The firm struggled on, attempting to fix the

problem, and in 1999 built 26 carburetted, 91kW ‘Trofeo’ versions of the V-Due for a one-make race series. But even then there were failures and, faced with little prospect of solving the engine’s problems and huge losses from buying bikes back from customers, Bimota hit the rocks.

That might have been the end, for both Bimota and the V-Due. But in fact both lived on, albeit in separate lives.

In a bankruptcy sale in 2003 a new group of investors bought the Bimota company, but the V-Due project – including the intellectual property, all the remaining stocks of unsold bikes and the ones that Bimota had bought back – was sold separately to former Bimota engineer Piero Caronni. He created the 2003 ‘Evoluzione’ version of the bike, with carbs, and later the ‘Evoluzione 04’ in 2004, with an extra 7.5kW. In total, 141 Evoluzione and Evoluzione 04 models were made, and Caronni also offered a service to convert original injected bikes to Evoluzione spec.

As a last hurrah, Caronni’s company, V-Due SRL, created the 2005 Edizione Finale. This was a track-only version making as much as 97kW with a fully sorted carb-fed version of the engine.

Bob Steinbugler of specialists Bimota Spirit in North Carolina says that, while switching to carbs solved some problems, the V-Due’s bigger issue was the crankcase seals.

“These seals were too small and not up to the task of sealing the crankshafts,” Steinbugler explains. “They would allow small amounts of air to be sucked past them, and that phenomenon in a two-stroke changes the mixture. The amount of air varied over time and from V-Due to V-Due, so it couldn’t be tuned out.

“For the Trofeo series, Bimota changed from fuel injection to carburettors initially and nothing really improved. Upon further observation they discovered the crankcase seal problem. This was a difficult problem to solve because there was not enough material in the crankcase castings to machine a pocket for a larger outside diameter seal to fit the crankshaft and seal it better. They used a seal that was the same outside diameter and had a smaller inside diameter, but to do this they had to machine down the ends of the crankshafts. This then led to some crankshaft failures.

“The main investment that Piero Caronni made was to go back to the foundry and have crankcases re-cast with a new design that added some material around the crankshaft holes to accept better seals. Once this was done, the bikes became predictable and consistent. The fuel-injection system still suffered from lack of development time – the original prototypes used fuel-injectors supplied by Ferrari and were precise in the range that the V-Due required. For the production versions these were not available, so they went to a production injector and these were not precise enough at the low volume end and did not have enough mapping development to sort them out really well.

“The combination of the new crankcase seals and carburettors has delivered on most of the original promise. Over 100hp [75kW] perfectly running, sweet-handling bikes. It’s unfortunate that it took so long to arrive at this point and that the vision of the direct injection was lost – I’m sure that direct injection could be achieved if the proper resources were put to the task of developing it.”

Now, 20 years on, the direct fuel injection that was both the V-Due’s main selling point and its

fatal flaw would likely be less of an issue. Modern injectors atomise fuel more efficiently and direct injection is increasingly mainstream. There’s a small industry involved in finding solutions to V-Due problems, and a growing number of owners now claim to have bikes that finally live up to their original billing – two-stroke GP-style performance and handling in one of the best-looking packages ever sold.

V-Due prices today certainly belie the bike’s troubled reputation. In 2003, Piero Caronni would sell you an original injected bike – brand new but still with all the inherent problems – for around A$16,300. Now you might need closer to A$40,000 to buy a second-hand one.

That’s a hell of a jump for a bike that’s best remembered as a failure, and shows that despite this status there are still plenty of people who dream of making the last of the great two-stroke roadbikes fulfil its initial promise.

Instead of saving the two-stroke, the V-Due’s failure cemented the idea in most riders’ minds that combining clean emissions and two-stroke performance was an unworkable dream. But what if that injected stroker really had met both its performance goals and emissions limits? Perhaps Honda’s investigations into clean two-strokes, demonstrated on its EXP-2 prototype in 1995, wouldn’t have been mothballed. Perhaps Orbital’s direct injection would have been adopted by Bimota’s rivals. And if the technology had still been relevant, MotoGP might have even remained a two-stroke class, and today we might be living in a world of screaming two-stroke superbikes.

The Bimota 500 V-Due could have changed the face of motorcycling as we know it. If only it had worked.