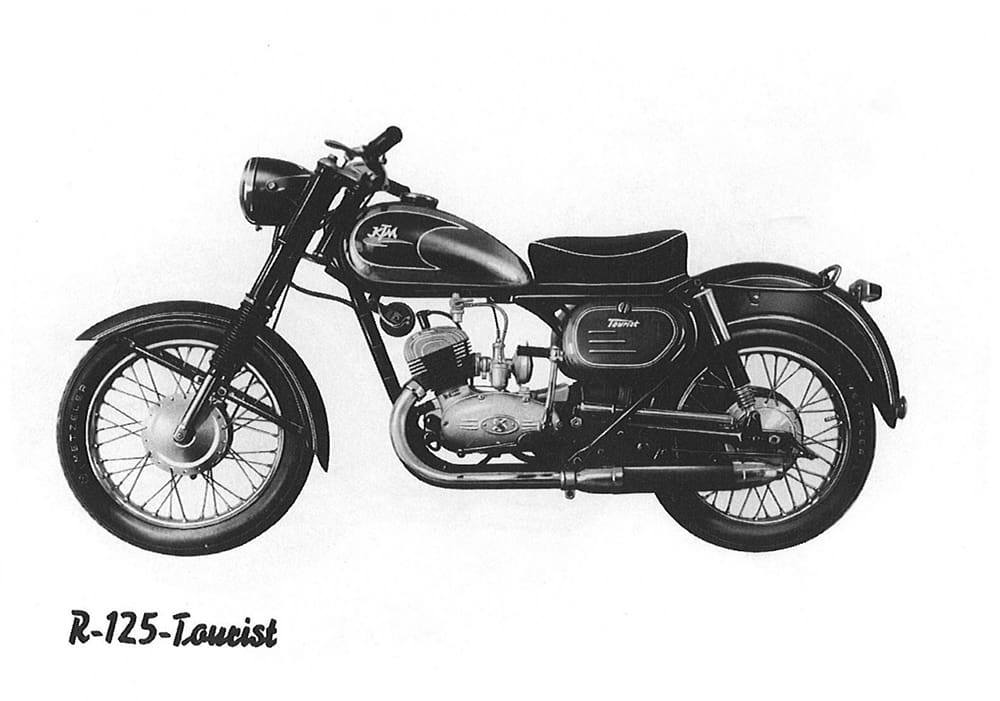

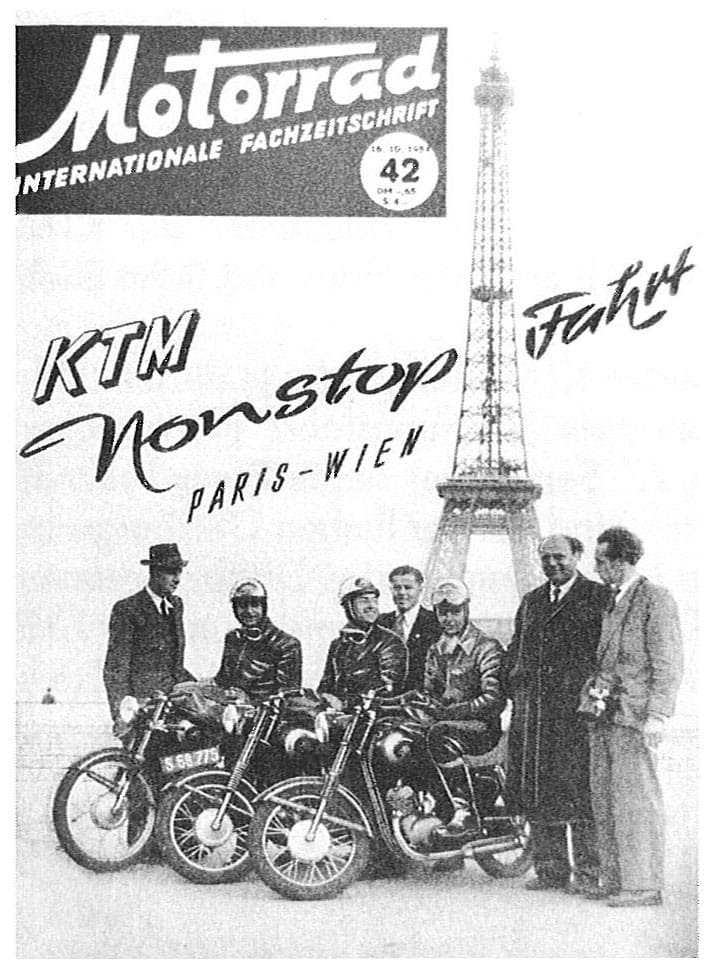

On 30 September 1954, KTM founder Hans Trunkenpolz sat on a 125cc motorcycle in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower in Paris. Facing a daunting non-stop 1300-kilometre ride, the 45-year-old Austrian knew the next 24 hours were crucial. Success would validate both the R125 Tourist underneath him and, more importantly, the vehicle repair company he set up 20 years prior – which had just dipped its toes into building its very first bike.

Failure would mean public humiliation, and possibly a premature end, for both the bike and the company.

Accompanied by fellow riders Paul Schwarz and Albert Brenter on identical machines, Trunkenpolz set his sights on his homeland’s capital. The trio believed this new 4.5kW machine could travel from Paris to Vienna faster than a train, which took a full 24 hours to complete the journey. But with a top speed of just 90km/h, the 125cc bike would need to be ridden flat out, day and night, stopping only for petrol and sustenance. Sure enough, after 21 hours and 41 minutes, all three arrived at the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, publicly proving the speed and reliability of the R125 Tourist.

So, 60 years to the day later, I also sat on a KTM 125cc motorcycle, in the same shadow of the Eiffel Tower. A shiver formed on my neck and wriggled its way slowly down my spine. Vienna hasn’t moved any closer in the past six decades. And while the RC125 beneath me might be a little faster than an R125 Tourist, it’s still an unlikely candidate for a non-stop 1300-kilometre ride. Besides, unlike Hans, Paul and Albert, I don’t have a team of support vehicles accompanying me.

Though the world is more familiar with KTM today, the company’s latest 125 still has a question mark hanging over its head. As with the 125, 200 and 390 Dukes before it, the RC125 isn’t built at KTM’s main factory in Austria, but by Bajaj in India. Sixty years on, this 1300-kilometre challenge will once again serve as a solid acid test of a bike’s build quality.

Sixty years apart

Whatever concerns were on Trunkenpolz’s mind that morning in 1954, it probably wasn’t dealing with this much traffic.

And it certainly wasn’t surviving the permanently congested Périphérique, Paris’s four-lane ring road which wasn’t even built 60 years ago. But at least I’m on something slim and light. The RC125 effortlessly dissolves into traffic as I slip sweetly and neatly through a sea of car mirrors.

Multi-lane commuter chaos slowly fades the further we creep from Paris, aiming for the N4 to Nancy – the same route the original journey took. It finally filters to a single-lane road, ploughing straight through the middle of wide open French farmland. With little more than fields of corn stretching to the horizon, it’s not hard to imagine this could be the same view Trunkenpolz had.

Out here the RC125 sits at the 90km/h speed limit comfortably, the single-cylinder engine spinning over with a few thousand revs to spare in top gear. This was the absolute maximum speed of an R125 Tourist, but the RC still has enough in reserve to steal a few cheeky passes on slower trucks. This steady pace mixed with the sense of history and occasion is hugely enjoyable. After three hours and 260 kilometres, I swing off the N4 looking for petrol. I top the RC up with less than eight litres of petrol and buy lunch. I’m a fifth of the way there already. This is easy.

Welcome to Germany

The N4 skirts round Nancy and charges east towards Germany. It’s mostly dual carriageway now, making the RC feel much busier and buzzier. The 11kW engine can just about pull to the 110km/h speed limit, but with far fewer revs left and the throttle now regularly held to the stop.

Even though the engine starts to feel strained, I don’t. The RC125 is surprisingly full-sized, with reasonable room for my 1.75-metre frame. Seat-to-peg distance is fine, and the clip-on bars aren’t wrist-heavy. The seat is small, though this bike has the benefit of KTM’s plusher PowerParts comfort item. A taller screen also claims to improve wind protection.

So far, the RC is behaving impeccably. On the original trip 60 years ago, the three men had already stopped twice in the first few hours: once for Paul Schwarz to change a jet in his carburettor; and once to replace a broken fork leg on Trunkenpolz’s bike. I look down at the RC’s sturdy-looking upside-down fork and cross mental fingers. But the RC’s serious-looking components aren’t just for show. A rare roundabout along the N4 after a long dual carriageway run is too precious to waste. A few needless knee-down laps lets off a little steam and shows the RC125 has a true sporty side behind its full-faired image. Bet Trunkenpolz never got to do that on his bike.

The N4 carries on into Strasbourg. Riding over the Rhein into Germany is done with so little fuss I double back to check I really have just crossed an international border.

But all doubts are dispelled when I hit the autobahn and, instantly, the RC125 feels woefully slow. The traffic is startlingly fast – and it’s not all speedy Ferraris and Porsches, but humdrum household cars blasting past a good 70 or 80km/h quicker.

Stopping to refuel is a welcome relief from the intimidating intensity of it all.

Sausages and coffee

The sun sets as I follow signs north to join the Karlsruhe-Stuttgart-Munich autobahn, just as the KTM crew did 60 years ago. Wearing goggles and pudding basin helmets, they certainly never had to think about swapping a tinted visor for a clear one. With light fading fast, I wish I had. But I’m not pulling over again now, fearful any non-essential stop could delay me beyond the 24-hour target.

It’s a mistake. Mist and fog compound the darkness, while the RC125’s single projector dipped beam is hopeless. Moisture accumulates on my visor, and when I eventually brush a glove across, it only succeeds in smearing 350 kilometres of splattered flies across my eyeline. Lacking in speed and now vision too, things feel a much more serious.

And realising that even after a full day’s ride I’m not even halfway there gives morale a kicking. It’s gutting to know it would still be quicker to turn around and head back to Paris than carry on to Vienna.

The motorway twists and turns uphill and the RC struggles. I need to drop back to fifth gear when the speed falls to 90km/h. Thankfully this gives more time to spot the stream of brake lights up ahead. Traffic has come to a stop and many drivers are out of their cars, standing on the road. I filter gingerly between them, relieved to be able to lift my visor and not worry about being the slowest thing on the road for a few kilometres.

When the traffic starts to move, once again I’m back to being a very small fish in a very big pond. And then it starts to rain. Waterproofs are in my bag, but I’ll be pulling over for fuel in half an hour or so anyway, and decide there’s no point stopping twice.

Another mistake. By the time I find services, just past Ulm late in the evening, I’m cold, wet and only just past the halfway point. I fill the RC for the third time and head inside for some food.

The Burger King here would be easy, but it doesn’t seem in keeping with the spirit of the trip – the firm didn’t open their first restaurant until December 1954. A magazine report of the original journey shows riders tucking into sausages and coffee, so I order that from the restaurant instead. I hope it works.

Cat and mouse

Waterproofs pulled over a belly full of pork and nerves, I head back out into the night. The 100 kilometres to Munich takes an hour, and the long ring road ride around the city begins just after midnight. As the rain gets heavier, I realise one thing missing from German autobahns: cats’ eyes. Not only are these motorways not lit, there’s nothing to help spot the lanes at night.

I switch to high beam and leave it on permanently.

The drizzling darkness is relentlessly demanding. Judging closing speeds from trucks’ tail lights is exhausting when you’re also checking those pinpoints of light in the mirrors won’t suddenly explode into a 200km/h Audi. Holding the RC125 around 110km/h on the autobahn feels like being both cat and mouse at the same time.

After just two hours’ riding I stop again. The bike still has petrol and continues to run faultlessly, but the fleshy bit on top isn’t quite as reliable. It’s past 1am and my concentration is shot. I fill up again and, being only about an hour from Salzburg, take the opportunity to buy a toll pass from the petrol station to allow me on Austrian motorways. I give a can of Red Bull half an hour to work its magic, then carry on.

Sweet amnesia

Pitch-black motorways have stretched to infinity. After hours of identical darkness there’s no sense of perspective any more, no sight of changing landscape to help judge my progress – just an incessant grind onwards, onwards, onwards.

Distance signs offer brief relief: Salzburg 100km. Salzburg 80km. Salzburg 50km. Salzburg 30km. Every sign passed feels like a small victory, but whenever one objective is reached, a new one takes its place: Wels 100km. Wels 80km. Wels 50km.

The only way to deal with the apparent futility is to forget it all. Switch off short term memory and, if you can’t remember, it never really happened. Live in the moment, then let it vanish forever. When nothing happens, hours pass in seconds.

Most of the time I lean on my left forearm which rests on the tank – comfy until my shoulder falls asleep. Stretching legs out to relieve aching knees, I feel pools of water in my boots slosh from heels to toes. It’s strangely satisfying.

When I stop again, it’s 4am. Only freaks and weirdos are up at this hour, especially at a motorway petrol station somewhere in the middle of Austria. I find a quiet corner and shut my eyes for just a second.

Oh… Vienna

Two hours later. I’m still sat in my quiet corner. It’s still dark outside. It’s still raining. And Vienna is frustratingly still more than 170 kilometres away. Damn.

But eventually, almost reluctantly, houses appear dotted among trees in the distance. A sign of civilisation. Street lights in Vienna’s suburbs at last announce the end of the motorway.

My finish line remains the Schönbrunn Palace, just as it was in 1954. When it quietly slips into view, behind gates guarded by a pair of golden eagles, the absurdity of the whole trip seems laughable, but the internal satisfaction is immense. Just 20 hours ago I was in Paris, 1338 kilometres away. I’m faster than the original trio by nearly two hours.

As a coach offloads a fresh batch of tourists eager to gawp at the palace, I try to imagine how Hans Trunkenpolz felt looking at this landmark 60 years ago.

To have completed that ride at all still seems an achievement today.

To have managed it back then on a machine he’d built would have felt exponentially more significant. The hardship and exhaustion would have been instantly replaced by pride and optimism for the future.

Hans Trunkenpolz could never have imagined one day his little firm would grow into the largest motorcycle manufacturer in Europe, let alone that it would produce bikes in India.

Or that such a bike would, with no preparation and no support, complete the same incredible journey considerably faster and entirely fault-free. I reckon he’d be proud of the RC125.

Story Martin Fitz-Gibbons Photography Chippy Wood