Nothing succeeds like success, and English entrepreneur Paul Sleeman knows this better than most. In 2014 he brought Hesketh back to the marketplace with the limited edition ‘24’ V-twin streetfighter. Having now sold all 24 of these at £35,000 (approx. AU$56,000) a pop, he is following it up with the Hesketh Sonnet café racer. It’s an unlikely revival of a marque whose story has, from the beginning, been worthy of a Hollywood script.

Paul Sleeman, 52, is a mechanical design engineer whose London-based company Tullman Design has developed and manufactures the best-selling Diesel Key, a patented invention which makes it impossible to mistakenly fill a diesel-engined vehicle’s fuel tank with petrol. The generous profits generated by this and other Tullman Design products have allowed the British bike enthusiast and ‘70s Norton Commando owner to satisfy his ambition to become a motorcycle manufacturer. He duly acquired the rights to the Hesketh marque in a deal signed with Lord Alexander Hesketh in May 2010, and since then has been working to relaunch the brand with a range of V-twin motorcycles.

“It was only natural that people had their suspicions when we restarted Hesketh,” said Sleeman at the Sonnet’s public launch this year. “There’s been lots of small high-end motorcycle companies come and go over the past 20 years, and while we weren’t exactly criticised for making the 24, there was a slightly downbeat reaction to it – as if people were thinking, how can they possibly survive? Well, we’ve not only survived, but we’re prospering, too.

“We’ve found our two dozen customers for the 24 all over the world, with the majority in the UK, but we’ve sent bikes to Germany, Spain, Australia and Russia, and we’ve had rave reviews from all of them. It seems the Hesketh 24 completely lived up to our customers’ expectations, which is the most important thing you can ever do when you’re asking someone to part with a large sum of money on a promise as much as anything else. Now we have to show everybody that Hesketh is not a one-trick pony, and that’s what the Sonnet represents. In building this bike we’re showing the world we aren’t going anywhere for now but up, and we’ve got other exciting, quite different things in the pipeline.”

Indeed so. Sleeman has targeted selling 100 examples of the Sonnet in 2017 – a volume which he says will generate the funding to produce the next landmark model along the Hesketh comeback trail – a V4 streetfighter he terms “a big thuggish roadburner of a bike that will dominate the highway in terms of real world performance.”

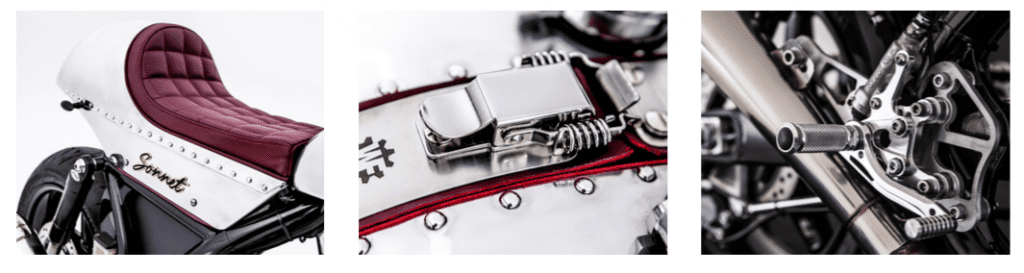

But that’s in the future, and the Sonnet is the here and now. The Sonnet is a continuation of its earlier sister bike’s Anglo-American theme, albeit a more conscious modern reinterpretation of a British café racer. Sleeman and his R&D team have swung the styling needle firmly back in time towards the Swinging Sixties.

Hesketh has also gone large. Powered by an uprated version of the same US-built S&S X-Wedge in the 24, the Sonnet boasts a capacity of 2163cc compared to its 1917cc sibling. Coupled with a sportier trio of camshafts with more lift and dwell, the ‘square’ 111.76 x 111.76 mm engine dimensions help deliver 108kW at 6000 rpm, a useful 15.7kw more than the earlier model, with a corresponding jump upwards in the bike’s massive tractor-like torque. The Sonnet now produces a hefty 210Nm at 3000 rpm, making it the most torquey series production twin-cylinder motorcycle available in the marketplace today, second only in absolute grunt to Triumph’s 221Nm, triple-cylinder Rocket. And yet, Sleeman has ended up providing Hesketh customers with more bike for less money. The Sonnet retails at a reduced GBP25,000 (just over AU$40,000), partly thanks to economies of scale in purchasing, and less costly suppliers.

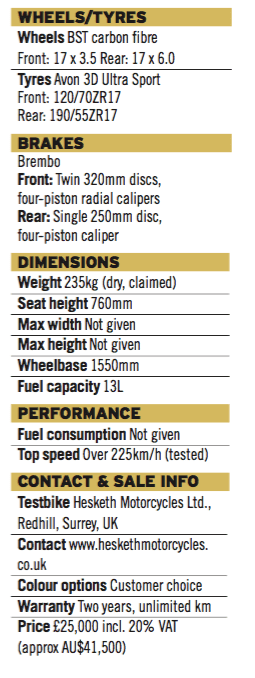

One look at the Sonnet tells you that this is a more potent, more muscular and simply more modern take both visually and dynamically on the café racer era. And this impression is confirmed when you throw a leg over its low 760mm seat, and reach a l-o-n-g way forward over the polished alloy fuel tank to the clip-on handlebars, mounted beneath the triple clamp.

But while the riding stance thus delivered is totally authentic, it’s not very comfortable for, er, more mature riders, who are likely to comprise the majority of Sonnet. That’s compounded by the rearset footrests being precisely that – they’re pretty far back, leaving you in a semi-forward inclined stance that also puts more weight on your wrists and shoulders. This at least helps load up the front wheel with your body weight for extra grip in turns, though it can get tiring in the process. What Sleeman needs to do here is to offer his clients the choice of a set of raised swans neck ’bars which will deliver a more upright riding position.

While we’re at it, another item on the to-do list is a redesign of the solo seat, so it narrows behind the fuel tank. It’s much too wide there at the moment, which is not only painful but also prevents you moving around easily on the bike in turns. It’ll be an easy fix, but Sleeman needs to pay some attention to getting the ergos right on the Sonnet.

That hand-beaten fuel tank’s left hand section in fact comprises the oil tank for the dry-sump S&S motor, complete with a neat dipstick that becomes accessible when you flip up the Monza filler cap, with the remaining real estate comprising the 13-litre fuel tank with an extension under the seat. That’s a little on the small side for such a big engine. The US-made two litre-plus V-twin motor employs a single injector per cylinder, and just one 52.4mm throttle body which doesn’t stick out unduly – so I never started fouling it with my right knee.

I actually had a double dip at riding the Sonnet. With just five miles showing on the Sonnet’s lonely-looking Koso speedo when I first rode it, the bike needed loosening up before I could form an opinion on it. So with that done, a couple of weeks later I met up again with Paul Sleeman and his Hesketh team headed by development engineer Iain Miles for a day’s ride in the Isle of Man, in the lead up to Classic TT week. With no speed limits outside towns and villages, this gave a great opportunity to mark the Sonnet’s report card as a high performance hotrod.

Which is what it surely is, in spite of still being way overgeared for my IoM ride. The Sonnet is the first modern Hesketh to employ a belt primary drive and Hesketh’s R&D team have guessed wrong on the gearing – it needs the equivalent of 3-4T more on the back wheel than at present. Still, thanks to the massive torque, acceleration is genuinely mind-blowing. Revs are almost irrelevant on the S&S motor – just thumb the starter button (no key, just a remote electronic sender unit you tuck into your jeans), relish the groundshaking presence as it fires up and settles to a lazy idle, then grab a big handful of clutch to engage bottom gear. A lighter clutch action than on the 24 makes riding the Sonnet in city traffic less tiring on your left hand, and the change action is now slicker, though it still pays to use the clutch for upward shifts in the bottom three gears to avoid jerking the drivetrain.

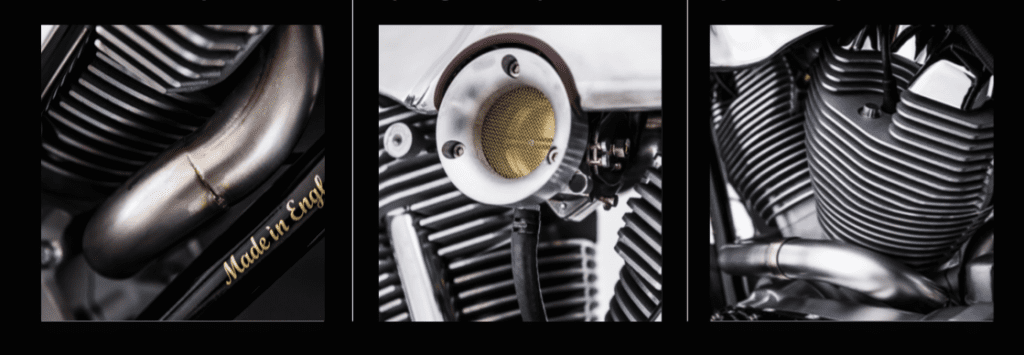

The S&S X-Wedge motor continues to be the most sophisticated-seeming American aftermarket big twin engine I’ve yet ridden, with dynamic qualities on a par with anything produced by Harley or Indian. It’s devoid of the rattles and shakes of most other such engines, with a pleasantly potent-sounding muscular roar emanating from the twin upswept exhausts either side of the bike, and a deliciously lumpy offbeat lilt. Although S&S disdains fitting a counterbalancer to iron out any vibes, it’s also very smooth, pulling cleanly off idle thanks to the huge amount of torque on tap at almost any revs – the only tingles you’re aware of come through the handlebars once you really get it revving.

By American V-twin standards it’s pretty refined in terms of operation, practically civilised – well, until you have the chance to exploit the humongous reserves of torque. Then it becomes seriously bad as well as heaps of fun, with awe-inspiring grunt out of turns coupled with remarkable competence in hustling through them.

The clutch barely needs to be troubled accelerating out of even the tightest turn from little more than walking pace, though you’re best off keeping the revs dialled up a little higher, again to avoid any hint of transmission snatch. But there’s acres of torque from there all the way to what transpires in the curious absence of a tacho (especially on a purported café racer) to be the 6000rpm revlimiter. But there’s no earthly point in revving the X-Wedge anywhere near that high. Instead, surf that so-strong torque curve and it takes very little time before you see the 100mph (160km/h) mark showing on the black-faced speedo. Still, you can’t resist blipping the throttle when changing gear, just to make music via that meaty-sounding exhaust, which issues a gratifying pop on the overrun after you shut off.

But the Sonnet isn’t just a point-and-squirt device. It’s a pretty capable corner carver, and the Avon 3D Ultra Sport tyres really help you to build confidence, whether carrying turn speed through fast sweepers, or delivering all that meaty torque to the ground via the fat rear, which grips well when you light the fuse cranked over out of tighter turns. It was the first time I’d ridden with these new Avon triple-compound tyres, and I found them impressive in harnessing the Hesketh’s massive muscle.

Equally satisfactory was the K-Tech suspension fitted to the Sonnet to replace the 24’s much dearer Öhlins hardware. It’s the first time the British race suspension specialists – whose products dominate BSB grids in most classes – have ever provided OE products for a street model, and I’ll admit to being a little leery of the change, which Paul Sleeman admits was driven by a desire to cut costs. But that was before I rode the Sonnet, and discovered the K-Tech equipment’s outstanding ride quality, especially over bumps. The fully adjustable KTR-2 upside down fork provides excellent front-end compliance – and heaps of confidence in attacking corners. Damping, however, is a little softer at both ends compared to the Swedish suspension on the 24.

That could be because the Öhlins shocks on that were quite stiffly sprung, presumably in order to avoid the S&S motor’s huge torque compressing the rear end when you get on the gas exiting a turn, and thus delivering substantial understeer. The Sonnet does suffer slightly from that, especially accelerating hard cranked over in the lower gears. And unfortunately, since the twin nitrogen-charged springless K-Tech Bullit shocks are completely non-adjustable, I couldn’t even crank up the spring preload to try to resolve this. A pair of longer shocks might be a fix, to lift up the rear end and throw more weight on to the front Avon. Ground clearance is already pretty good, with just the sidestand on the left grounding out occasionally as an early warning sign that you’ve reached the limit – no dramas, though.

You do feel very much in control of the new Hesketh, whose handling is almost intuitive in spite of being such a heavy package scaling 235kg dry, and with such a long 1560mm wheelbase. In spite of the long wheelbase it steers well, thanks mainly to feeling so well balanced. While the clip-on bars don’t provide much leverage, it’s not a problem because the geometry feels right. Lowering the cee-of-gee by positioning part of the fuel load down low helps improve manoeuvrability, so that while the steering feels heavy at low speed, it becomes sharper the faster you go, and the Sonnet changes direction well, without undue rider effort. That’s partly thanks to the reduced gyroscopic weight of the front BST carbon wheel. Besides being sun-glinting eye candy that lifts your spirits as you walk towards the bike ready to hop aboard, it helps sharpen the steering and improve suspension compliance via reduced unsprung weight. I’m glad Paul Sleeman’s cost-cutting exercise didn’t extend to ditching the South African-made round black featherlight gold ingots…

Incredibly, he’s also saved money by fitting Brembo brakes to replace the 24’s highly effective but also far more expensive Beringers. And they’re not just any Brembos, either, but top of the line radial four-piston Monobloc calipers gripping a pair of floating 320mm discs up front, with the same rear caliper and a 250mm disc. The result is that the Sonnet stops brilliantly from high speed thanks to the great bite delivered so controllably by these brakes, with zero stability issues thanks to the long wheelbase. The K-Tech fork is still stiffly enough sprung that the substantial ensuing weight transfer doesn’t collapse them, and stroking the front brake lever to lose a little speed in turns doesn’t get the Sonnet sitting up to try to head for the hedges.

Paul Sleeman and his Hesketh R&D team have succeeded in producing something very distinctive and worthwhile in the new Sonnet, a rorty, raw-edged and totally invigorating combination of American V-twin musclebike performance with British styling flair and handling capability. The new Hesketh delivers a completely unique blend of Anglo-American performance that nobody else offers on two wheels right now.

AT A GLANCE

X-Wedge’s mega grunt

Cooler and quieter

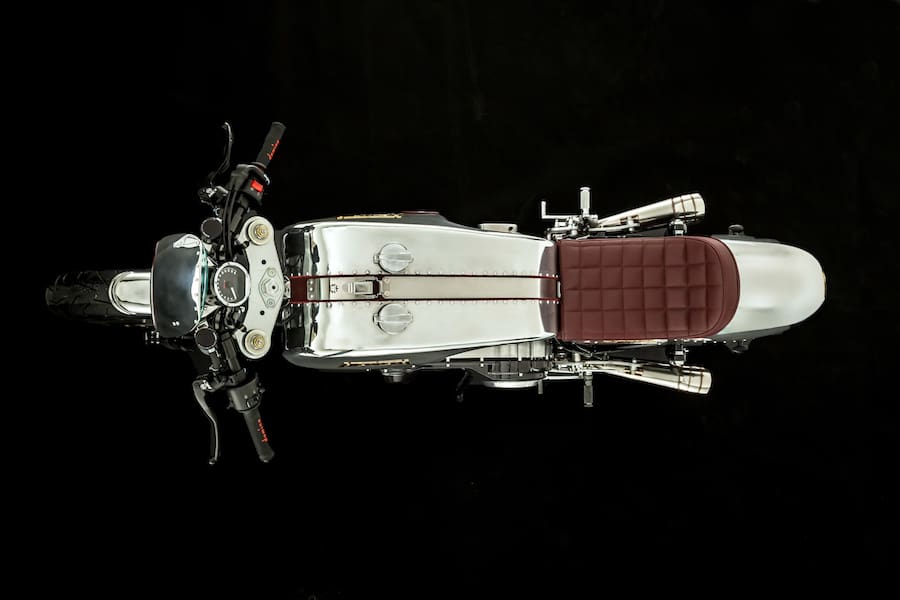

The XW124 version of the engine in the Sonnet measures a square 111.76 x 111.76mm for a capacity of 2163cc, and weighs 75kg before adding the single S&S 52.4mm throttle body mounted between the cylinders. The closed-loop fuel injection system pumps mixture into those two wedge-shaped combustion chambers contained in the five-stud cylinder heads, which have around 50 per cent more fin area than previous S&S Harley-type 45o engines. The X-Wedge is actually 5dB quieter than an old-type Sportster-style S&S engine from 2000rpm through to 5000rpm, says designer Jeff Bailey.

Playing the angles

To prevent the large-diameter forged Mahle pistons clashing their skirts near BDC, the cylinder angle has been increased to 56.25o. Each cylinder head has a fuel injector mounted directly in it for a straighter squirt and more efficient combustion, while the die-cast aluminium cylinders with cast-iron liners are interchangeable front and rear. The three camshafts are driven by a single Gates toothed belt, running in a dry timing chest on the right of the engine. The two separate exhaust cams flanking a common intake cam collectively achieve almost dead straight pushrod angles that create a very quiet, EPA-friendly valve train.

The Hesketh story…

Thomas Alexander Fermor-Hesketh, the third Baron Hesketh, KBE, PC was born in 1950, and inherited the title and wealth of Lord Hesketh at the age of four when his father died young. The family’s money was held in trust for Alexander, who didn’t inherit it until turning 21, so after tiring of life as a boarder at his British public school, he ran away aged just 16 to become an upmarket used car salesman. Stints as a stockbroker in San Francisco, and a ship broker in Hong Kong followed, before he returned to the UK and took up the life of a landed British nobleman whose family estate at Easton Neston was conveniently adjacent to the Silverstone motor racing circuit.

In his days in the used car trade Lord Hesketh had made friends with a charming but unsuccessful racing driver named Anthony ‘Bubbles’ Horsley (best not to ask why), who introduced Alexander to motor racing, and in 1972 to James Hunt, an impecunious fellow-racer from a similar public school background. Now aged 22, Hesketh decided to form his own racing team, together with Hunt as driver and ‘Bubbles’ as team manager, with such necessary accoutrements as a Bell Jet Ranger helicopter to get to and from the circuits, and a Rolls Royce for paddock transportation, as well as crates of champagne to provide refreshment, and a bevy of beautiful women to pour it, among other tasks.

Eschewing such tiresome necessities as any form of sponsorship, which might have prevented them from having a good time, the team was entirely bankrolled by the Hesketh cheque book and raced a car painted in patriotic red, white and blue livery under the slogan “Racing for Britain and for You”. Hunt paraded an alternative motto on his race suit: “Sex – Breakfast of Champions”! Inevitably, the rest of the Formula 1 paddock, encompassing such hard-nosed individuals as Bernie Ecclestone and Colin Chapman who’d fought their way up from humble beginnings, regarded Team Hesketh as a bunch of toffee-nosed buffoons with more money than sense. But when Hunt finished third in the Dutch GP at Zandvoort, to reach the rostrum in only his and Hesketh’s fourth F1 race, the sneers were wiped off their faces, and with eighth place in the championship at the end of their rookie F1 season, James Hunt and Hesketh Racing had arrived on the scene in a big way.

As more success followed in ’74 and ’75, the small privateer team became folk heroes in Britain – and elsewhere, too. Still gloriously unsponsored, they represented the triumph of the little guy working out of a stable workshop over their colossal and much better-equipped rivals, while having a bloody good time in the process. It was sport, not business – Hesketh in F1 was the last hurrah for the Corinthian principle in Formula 1 racing, even if bankrolled by a wealthy aristocrat.

But Alexander Hesketh’s funds began to run dry, and at the end of the ’75 season he sold the team. James Hunt moved to the rival McLaren team for 1976, and duly won the world championship. With Formula 1 off the agenda, Alexander Hesketh was persuaded to bankroll the revival of the failing British motorcycle industry. (Norton had gone bust, Triumph was in the hands of the soon-to-fail workers’ cooperative, and all other marques were already dead.) The Hesketh V1000 duly appeared in prototype form in 1978 and was unveiled to the press in 1980 in the presence of Mike Hailwood. Production began the following year with a 47-strong workforce recruited and a goal of producing 2000 motorcycles per year.

But there were numerous problems. Apart from a heavy, slow gearchange, there were constant oil leaks caused by differential expansion rates between engine components, as well as seizures caused by a lack of airflow to the overheating rear cylinder – issues which engine developer Weslake should certainly have addressed. As non-motorcycle people, Hesketh management realised too late they’d chosen the wrong developer, and the resultant bad press combined with an underdeveloped bike, spiralling costs, and a collapsing global motorcycle market, meant that after producing just 139 examples of the V1000 in total, Hesketh Motorcycles Ltd. went into receivership in 1983.

TEST ALAN CATHCART PHOTOGRAPHY KYOICHI NAKAMURA