Since the early 1950s the Pacific Highway has been the chief thoroughfare north out of Sydney, replacing the original route via the Wiseman’s Ferry punt that opened way back in 1829. The introduction of the Calga tollway in 1968 did two great things for motorcycling; it freed up the Pacific Highway between Berowra and Somersby to become northern Sydney’s chief racer road haunt, and made a trip to Surfers Paradise Raceway a 12-hour drive, but for the lead-footed, a sub 10-hour run. Equally, it made Amaroo and Oran Parks a viable weekend race option for Queenslanders, cementing the eastern seaboard as the motorcycle competition stronghold of Australia.

It was also a serious engineering triumph and a major piece of public infrastructure that happily remains toll-free in an era of expensive private toll roads in Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne.

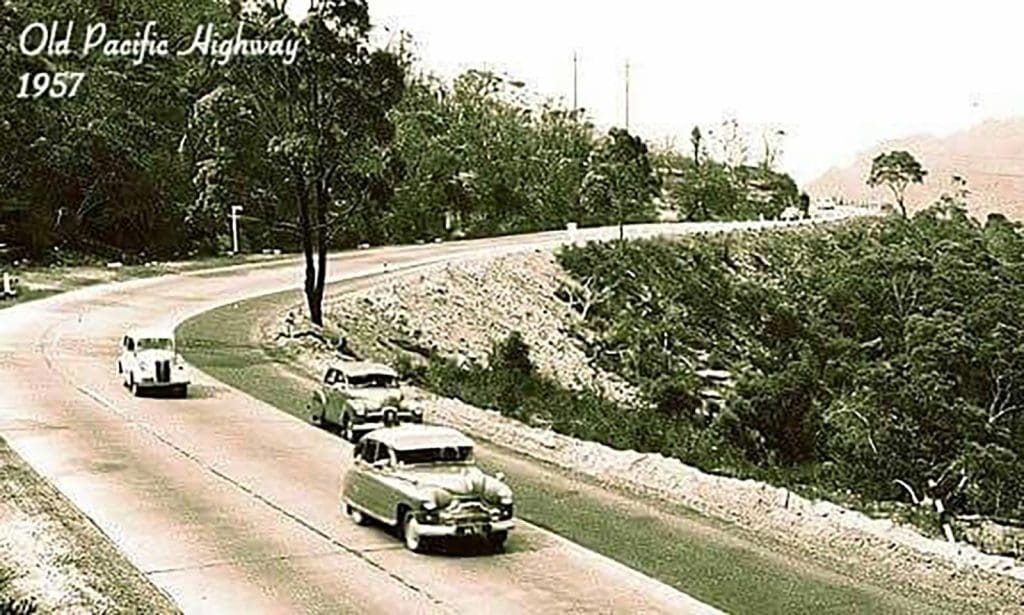

Urged on by the Queensland government, which was responsible for the short 100km stretch of Highway 1 from Brisbane to Tweed Heads, the first fully sealed 950km version of the Pacific Highway starting at Milson’s Point was completed in 1958. By 1962, the main route for the east side shuffle between Sin City and the Sunshine state was the most dangerous thoroughfare in Australia, having claimed more than 400 lives over the previous decade.

On 22 January, 1962, the NSW Labor government announced details of a £36 million Sydney-Newcastle highway in the lead-up to that year’s 3 March election. The new route would cut 32km off the existing 190km journey between the two cities on the Pacific Highway. Roads Minister Pat Hills announced the first toll section from north of Sydney at Berowra to the Hawkesbury River. It would be the first rural expressway built in NSW.

By early 1962, the Heffron Labor government had rejected four private proposals that, while producing shorter travel times, were deemed too expensive. The government’s plan saw the new highway head north-west to Mangrove Mountain then east around to Wyong, many kilometres away from the existing two-lane Pacific Highway that snaked through Gosford. The government’s plan met strong opposition from the Liberal-Country Party coalition, the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper, and NSW Central Coast interests.

A coalition of Central Coast businessmen, industrialists and civic leaders, calling itself the Sunshine Highway Committee, pushed for the new highway to be built along the edge of the burgeoning coast line to boost tourism and industry. The committee’s idea was for a privately built four-lane highway to run through Gosford, Bateau Bay and The Entrance to the east of Lake Macquarie then all the way to Newcastle, cutting 30km off the government’s planned road.

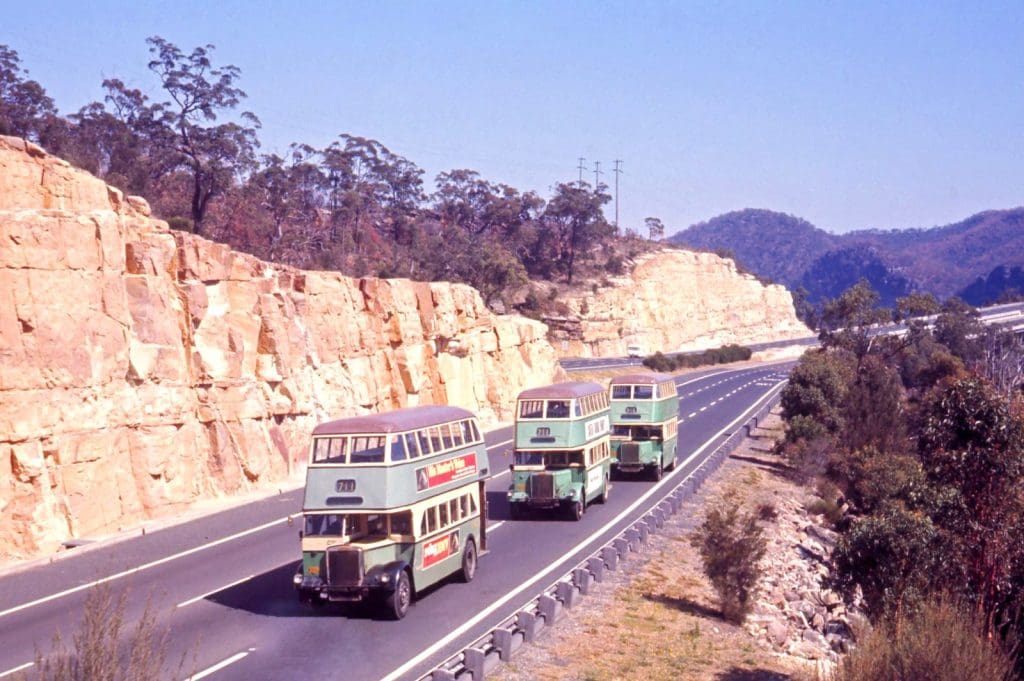

The Calga tollway was opened on 13 December, 1968, with the six-lane toll plaza located on the Mooney side of Hawkesbury River Bridge, eponymously referred to as the ‘Brooklyn Bridge’. The completed Berowra-Calga expressway was opened in October 1973 coinciding with the opening of Berowra’s 50c tollway and the closure of the Mooney toll plaza.

Australian racers who had ventured to the Continent in the 1950s and 1960s reckoned the engineering feat of the new expressway rivalled anything they saw in Europe. What impressed most were the spectacularly tall sandstone cuttings drilled and skilfully blasted through thousands of tonnes over many kilometres. To complete this stunning effect, crawler track-mounted drills burrowed down 4m and, when the rock strata was more favourable, 10m at a rate of 0.3m a minute. The blast compound was a mix of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil, the main charged primed by gelignite activated by electric detonators. The steep carbon-stained sandstone cuttings remain a spectacular signature of the expressway.

In the 1970s, the shuffle up and down the coast saw dozens of top riders engage in cross-country sprints in their trailer-towing sedans and utes. By the time they had reached their destination most riders were well primed for the racing that lay ahead.

Sydney A-grader Ross Hedley remembers the intensity of those crazy trips being as competitive as the racing itself.

“We had my dad’s Valiant and we’d leave after work and drive all through the night to Surfers Paradise, 12 hours straight, arrive at 6am, catch up a few zeds and wait for the gates to open.

“On the way, you’d have a race with the other guys. They were all gun drivers.

“You’d see Toombsie or (Bryan) Hindle and other boys on the road, and you’d have a drag to see who could get there the quickest. One time we got to Surfers and Toombsie pulled up just after us. He had towed his Hendo G50, a 350, 250 and the 125. A truck coming the other way had side-swiped his trailer and emptied all the bikes out, smashed and bashed.

“The camaraderie was fantastic, everyone rallied around; someone had a fairing, someone else had screens or levers and managed to get all of his bikes, in patchworks of colours and sizes, back together.”

Former racer Graeme Ausburn recalls Toombs and others ripping over hill and dale to the downhill run and ‘finish-line’ at Bangalow with dawn fast approaching.

Toombs sometimes caused a bit of mayhem on the way home. He rarely hung around for Sunday’s post-race drinks and was the first to head back to Sydney, tearing through the back-country villages of northern NSW. Alerts were raised and the next group of marauding utes were intercepted by the law.

On Friday 31 August, 1973, Chesterfield Superbike series leader Max Robinson was en-route to the Marlboro Two-Hour production race at Calder Park Raceway.

His car suffered a rear tyre blow-out near Glenrowan in northern Victoria. He attempted to correct the slide but the vehicle left the road and Robinson, 29, sustained fatal head injuries.

His wife Janice survived the accident. Pole position for the Calder two-hour was left vacant in his honour…

WORDS: DARRYL FLACK