HRC’s MotoGP woes peaked in 2023, so surely now the only way is up for Honda. The early stages of this season have demonstrated the Japanese factory is facing a long and complicated road back to the top of MotoGP. But at least the world’s biggest motorcycle manufacturer has shown initiative and direction in recent months.

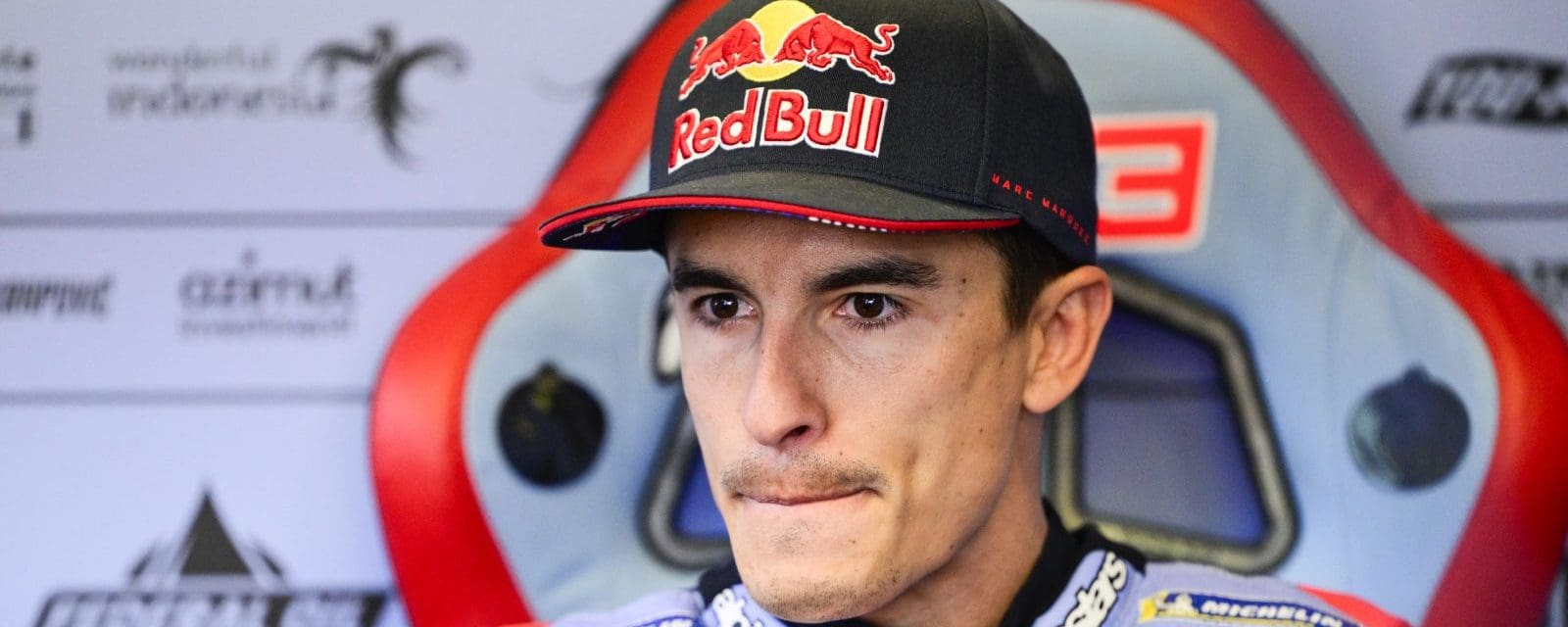

All that was seriously lacking this time last year. Whether it was Marc Marquez’s decision to leave the grid’s most successful team for Ducati’s third satellite squad, Joan Mir considering retirement after just a handful of rounds on the RC213V, or Alex Rins – the sole rider to win for Honda through all of last year – slipping through their fingers, 2023 was painful viewing for anyone associated with HRC. The manufacturer lurched from one crisis to another.

Such situations raised serious questions regarding its MotoGP future. Yet HRC president Koji Watanabe reconfirmed his commitment to the class last summer. While they were unable to convince Marquez to stay, new concessions have granted Honda unlimited testing in 2024. Now its engine and aerodynamics can be developed throughout the season, a freedom not enjoyed by MotoGP’s leading factories, an opportunity awaits.

“For six years I didn’t see anything like the commitment they’re showing now,” said one figure connected to the Repsol Honda Team at the 2024 Portuguese Grand Prix. AMCN spoke to people associated with the factory to understand how Honda finds itself in this predicament and the steps it’s taking to get out of it.

THE ROAD TO NOW

Honda’s dramatic turn for the worse coincided with Marquez entering his own personal hell. That career-defining crash at Jerez in the July 2020 and complications that arose from it ravaged the eight-time world champ for three years, as he raced at just 50 percent of the 52 MotoGPs from 2020 to 2022. This disrupted the team’s rhythm.

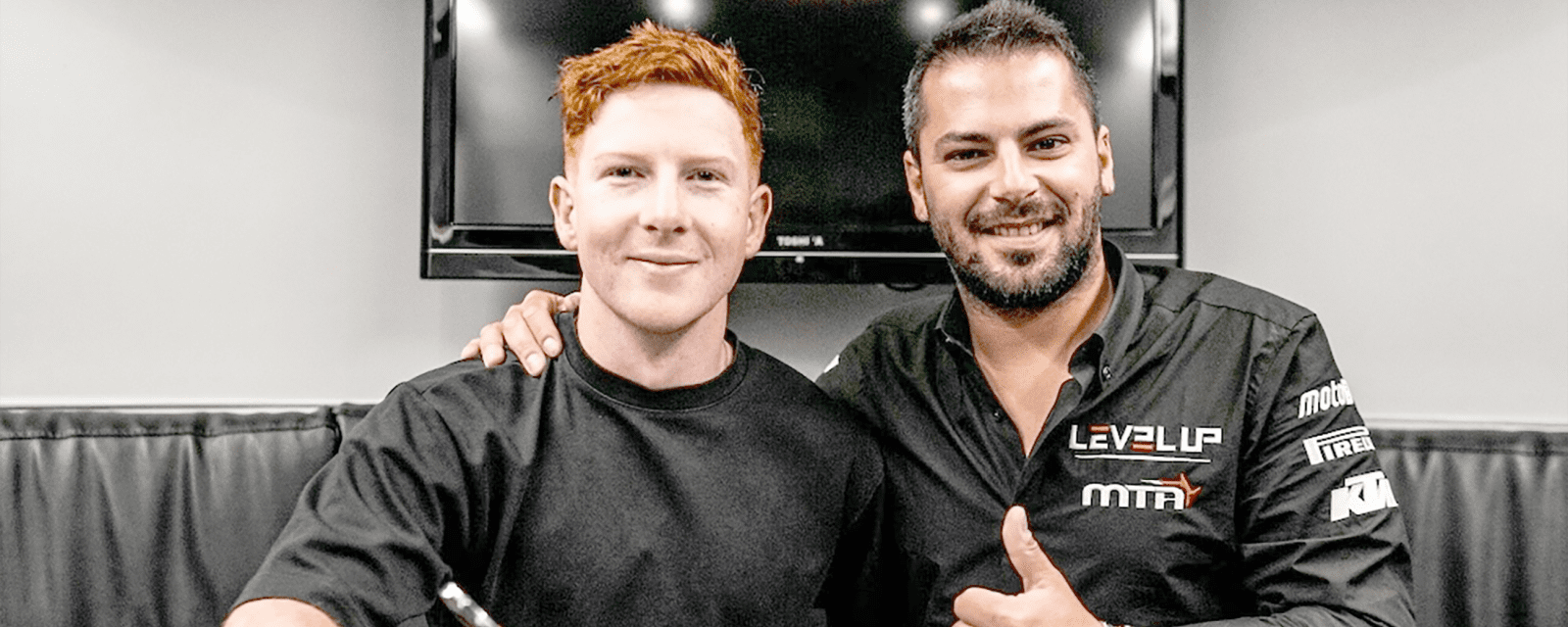

“It didn’t help Marc had a serious injury and he kept postponing his comeback,” explained LCR Honda team manager Lucio Cecchinello. “He’s not only a great rider; but he was a great leader inside Honda. Honda has a lot of consideration for him. They kept waiting to hear his comments on which direction they should go.”

There is now an admission behind the scenes that many Honda engineers felt Marquez simply returning would immediately elevate their fortunes. LCR’s technical director Christophe Bourguignon admits as much.

“We had Marc covering the weakness of the bike,” he said. “Probably they were waiting too much on him to find his good moment and (thinking) all would be beautiful when he did.”

Little did they know that not even a rider of Marquez’s calibre could mask the deficiencies of the RC213V.

Secondly, the effect of the global pandemic on MotoGP’s Japanese factories cannot be overstated.

“They just had a couple of engineers going around racetracks, sending emails and data back to Japan,” said Cecchinello of that time from 2020 to early 2022, when serious global travel restrictions were in place.

Unfortunately for Honda, this coincided with Ducati, Aprilia and KTM upping the stakes in the premier class. At certain tracks, race records were shattered by 10 seconds or more.

Honda was also slow to react to its rivals’ gains in the aerodynamic field, as well as the ride height and start devices.

“Probably the development department inside HRC, without seeing with their own eyes what was going on at the racetrack, how the competitors were moving forward, applying new, unconventional technologies… played an important role in our bike development,” admitted Cecchinello.

It wasn’t just the bikes that were changing; the off-track approach was, too. As Bourguignon stated, “(In those years the European manufacturers) started hiring technicians from other manufacturers and having their own aero department, wind tunnel, things like this. Aprilia had all these F1 people coming into the game.”

Like Yamaha, Honda was extremely slow to react. By the time it did, it found itself years behind the curve.

Lastly, question marks over the organisation of Honda’s MotoGP project were brought into focus at the start of 2022, when confusion meant test rider Stefan Bradl’s bike or leathers didn’t turn up in time for the Sepang shakedown – a gross logistical oversight saw the German testing at Jerez just a few days before.

That was only the start of it. So perplexed were engineers at the RC213V’s behaviour at the start of 2023, they asked Marquez to ride without any aerodynamics at the Sepang test. As European manufacturers perfected bikes designed around their respective aero packages it demonstrated just how far HRC trailed.

This was another event which fueled the Catalan’s questioning of whether Honda had the nous to get out of this crisis.

Then there was the treatment of Rins. With Marquez absent from last year’s Argentinean and American rounds, the recent arrival from Suzuki grew dissatisfied at not receiving the latest parts in LCR.

“Honda needed to commit 100 percent toward Marc,” said Cecchinello, “because he had already informed Honda, ‘Hey guys, I want a winning bike and if not, I’ll consider other options.’ They felt a lot of responsibility (and) needed to face (the situation) with limited capacity production of some parts.”

Still, during the early season Rins and LCR engineers pushed HRC for updated aero packages which offered more downforce. When he tested numerous aero options at the Jerez test last May and none had the intended effect, Rins decided his time there would be short lived.

With the factory struggling, why not look elsewhere for brainpower? Team manager Alberto Puig tried, as he sought to bring in engineers from Ducati for 2023. Yet it was revealed this was rejected by Honda’s top brass. They wanted to do it their way.

Overall, Honda’s approach was too conservative and stale compared to the Europeans.

NEW TALENT

The hiring of Ken Kawauchi from Suzuki at the start of 2023 addressed the disorganisation and opened communication to the factory. Takeo Yokoyama made way for his compatriot. There have been other notable changes, too. HRC general manager Tetsuhiro Kuwata has been relocated this year, while divisive long-time HRC director Shinichi Kokubu was moved on last October, with Shin Sato brought in as replacement. Some felt Kokubu’s intimidating demeanour did little to encourage or inspire the less-experienced engineers in his ranks.

“The fact they engaged Ken Kawauchi was part of the project to increase the communication link between racetrack and what’s passed to the R&D division,” said Cecchinello. “Of course, the distance plays a difficult item in the middle. Aprilia, Ducati or KTM, after a race week go back together to the warehouse and can have open and deep discussions. They have many more people that can talk face to face. While in Japan they’re just receiving emails. I’d like to see, let’s say, more opportunities to meet each other during the year, to make it closer.”

There was also a serious recommitment from Watanabe last summer. Suddenly a greater number of engineers were present at the track toward the end of 2023.

“From what I have heard from the HRC president, there is the full commitment of Honda Motor to increase the budget for racing,” said Cecchinello. “Honda don’t have to prove their technology. They’re able to build a winning Formula 1 engine, robots, planes, winning off-road machines. I’m sure they’ll be back. But it’s a matter of time and budget.

“They’re increasing manpower and the number of engineers involved in the project. I don’t see any action trying to economise expenses. They’re really focused on making it happen.”

“I see many new faces,” said Bourguignon at the end of last year. “A lot of people from R&D. They have clearly invested human resources and financially in the aero studies in Japan. It’s clear we now see some engineers that aren’t just specific to the chassis; they’re specific to aero.”

As if to demonstrate how it can flex its muscle, Honda built a completely new bike in the two months between the Misano and Valencia tests last year, while further improvements were made before preseason. There are even claims the new machine weighs 8kg less than its predecessor.

WIDER EXPERIENCE

It was no coincidence Honda’s two new riders for 2024 have a combined seven years of experience aboard all-conquering Ducati machinery. Honda is hopeful Luca Marini and Johann Zarco can provide development direction.

“Johann is not a beginner,” said Bourguignon. “One hundred percent he’ll be able to give us some direction to help us understand where we can improve our bike.”

Marini has already offered up advice on how the aerodynamics engineers can improve the RC213V’s level.

“They started with new people, aero engineers that are new for this year. And I gave them good ideas,” said the Italian at Sepang.

One of the few bright spots of the Qatar test was an improved aero package that all riders liked.

Honda is also calling upon Alex Baumgartel, the genius behind Kalex’s Moto2 domination. In his role as technical adviser, Honda hopes he can aid chassis development in the months to come. And Cecchinello revealed HRC is ensuring it is not short on new parts, as it was with the Rins situation last year.

“Now they are making agreements with new suppliers around the world and are fully committed to improving that area,” he said.

WORKING AS ONE

Ducati’s success doesn’t just lie in having the best bike; its structure is built around optimising its resources. General manager Gigi Dall’Igna regularly checks in on its satellite teams, while all eight riders can compare data to improve settings or riding style. In the past, Honda’s approach wasn’t always as joined up, something which dismayed Pol Espargaro – a Repsol Honda rider in 2021 and 2022 – who saw every rider and their own team working for themselves.

Yet after the Sepang shakedown in February, Takaaki Nakagami noted how Honda was debriefing and pooling information with all four of its riders.

“(Now) the factory and satellite teams are a unit,” he said. “(Japanese engineers) come to our garage more often. I feel it’s more like one Honda family.” Bourguignon agreed. “We’ll try to be more open between all of us to share the workload about development, to do back-to-back tests and comparisons when we choose the direction, so it’s not a ‘maybe’ direction; it’s a ‘sure’ direction.”

One Honda insider noted an increased presence of HRC office staff at the track during preseason, as it bids to strengthen communication between track and factory.

This also includes the test team taking on greater responsibility as it seeks to take advantage of the new concessions. In 2024, it will participate in a total of 22 events, including tests and wildcard appearances.

ONWARDS AND UPWARDS

The early races have shown Honda still trails Ducati by some distance. And there are real concerns over the early performances of new signing Luca Marini, who finished 20th (42 seconds behind the victor), 17th (40 seconds back) and 16th (34 seconds back) in Qatar, Portugal and Texas respectively.

But at least HRC is addressing its weaknesses, both on the bike and in its approach. Joan Mir – now working with Marquez’s old crew – has stepped up to become Repsol Honda’s lead rider. He is riding with more assurance than at any point last year. It’s fair to not expect too much in the season’s first half.

“The aim is to be more competitive in the second half of the year,” said Puig.

Cecchinello felt it could be even longer to return to the top. “To build a real competitive bike for any rider, yes, we need more than one year,” he said. “I think to be able to build a bike for one special, talented rider at a special racetrack, it’s possible to achieve wins, as we already proved last year with Alex Rins.”

Bourguignon concurred: “After all, we are not looking into a crystal ball. It’s difficult to know if it will take half a season this year to (be competitive). The atmosphere is good and the way you feel that you are part of a project that really wants to move forward is quite nice. The positive thing is the attitude is good at the moment. And there’s no reason why Honda can’t build a winning bike.”

WORDS: NEIL MORRISON PHOTOS: GOLD&GOOSE