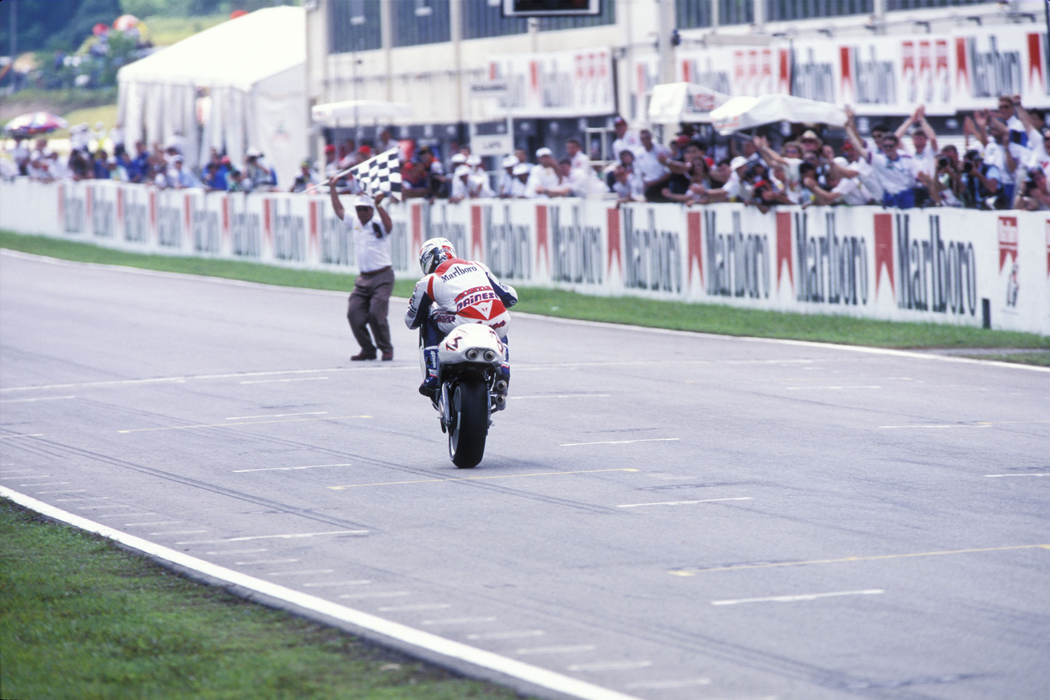

Luca Cadalora’s bike was easy to spot on the brightly coloured 1996 premier-class grid. In amongst world champion Mick Doohan’s unmissable turquoise-and-orange Repsol Honda livery, Alex Barros’ striking yellow-and-green representation of the Brazilian flag and the factory Yamahas’ blazing Marlboro red sat the Italian’s plain white NSR500. No sponsors on the sides of the fairings, where a huge empty space looked like a bold statement: I’ll try to beat the Australian on a similar bike, with bugger-all money and support.

The former 125cc and dual 250cc world champion was coming from three seasons with the Roberts Marlboro Yamaha squad, winning two races each year, for a total of six. Feeling like he was racing with an inferior package, he opted for a surprising move riding an unsupported Honda NSR500 in the belief it would give him the opportunity to show his real value.

This, in his words, is the story of how it all unfolded.

Could your move be defined as crazy?

I simply followed my heart. I felt I had to do it and I committed to it. Of course, it was a big gamble. In some way, what I expressed was some sort of rebellion: it was a reaction to the choices made by my previous team lead by three-time world champion Kenny Roberts.

What was the reason behind the divorce with the team that made you debut in the top class in 1993, with Wayne Rainey as your teammate?

We had Dunlop tyres and I wanted to race with Michelins, like most of the grid. In 1994 I had finished the season in second overall, so my results were not bad. But Dunlops were always a question mark: working really well on one track, on the following they could be a disaster. It was super stressing and I was tired of that.

You went from having a Yamaha factory ride to being a private Honda rider: how was the change?

The first preseason test in Phillip Island was a complete disaster. My NSR had Doohan’s same setting and I didn’t like it. I also had a huge crash. A footpeg made a hole in my leg, a big one, close to the femoral artery. I left Australia in pain and worried.

The second test was in Malaysia, which was going to stage the first race of the calendar. How did it go?

My crew chief Erv Kanemoto, between the two tests, worked a lot on the bike in order to fulfil my requests and the result was great. In Shah Alam the feeling was good and the Showa technician supported us greatly, letting me try lots of things and listening to all my comments and demands. Of course, he was doing it also at his own advantage. They were developing their material and apparently I was a big help.

How did the relationship with Showa evolve?

They offered us the same treatment of the factory teams. But the financial request was incredibly high, above any reasonable amount. I thought: are they crazy? After all the work we did in Malaysia in order to make their stuff work, that was the way they were repaying us? I didn’t like that behaviour.

The first race came and you won it!

I expected somebody from Honda to come and shake hands with us, saying ‘congratulations guys’. But it didn’t happen. It felt like we had done something wrong.

How did things with Honda develop?

Malaysia was the start of a war. The funny thing is: the way we reacted gave them even more trouble. Before the fourth round of the championship, in Jerez, we asked HRC if we could switch from Showa, which was linked to Honda, to Öhlins. I was convinced that if we bought an Öhlins front fork, which would cost us less than a tenth of what Showa had asked us for a factory treatment, and work on it, we would have very good material in our hands. Erv had excellent skills; that was the reason.

Did they allow you to change?

Incredibly, Honda gave us permission. So we went to Jerez with a new front fork and during the whole race I was able to stay with the two factory riders, Alex Criville and Mick Doohan, keeping more or less their pace. The problem for HRC was that after my performance, other satellite teams became interested in switching to Öhlins.

What were your requests in terms of suspension settings?

I’ll make it short. There are two kind of riders. One type likes a stiff bike that needs to be forced, or somehow contrasted, so they use their energy to ride. The second category, on the other hand, feel and follow the movement of a ‘softer’ bike, so they’re less physical in their style and take advantage of the inertia forces, the changes in the centre of gravity, and so on. I was part of the second type.

What was the feeling when the bike was working well?

It was amazing. Like being one with the machine. The motorcycle became an extension of my body. I could feel the rear with my bottom through the seat, and the front with my arms through the fork.

In 1996 you finished third in the championship, like the previous year with Roberts, collecting eight points less, but with two more races in the calendar. The best Yamaha rider was Norifumi Abe in fifth. After Malaysia you were able to win in Germany, beating Doohan in the final stages of that race.

At the Nurburgring we had to lap many riders and had to take some risks, but it worked well for me. During my career I had the privilege to battle with talents like Mick, [Wayne] Rainey and Kevin Schwantz. Really amazing riders that could do incredible things. It was always hard to say what the limit was for them.

What was your approach towards your opponents?

I never rode against somebody. Well, maybe it happened at the very beginning of my career, but I quickly understood it was not the right thing to do for me. I wanted to be the fastest, no matter what. I didn’t care about who I was racing against. So I can say I was racing for myself, for my pure pleasure.

I had started because of a positive reason, trying to fulfil the dream that my father had to give up when he started our family, something he kept secret until I was a teenager. In order to perform well, I had to be happy. I couldn’t be angry or against somebody. At the same time, I recognise that some riders can have that kind of motivation.

Is it true that during your years with Roberts, in the mid-1990s, you studied the bike’s behaviour through videos?

We had a system that made the images go slow so we could see, for example, if during braking my front fork was working differently compared to Wayne’s. It was helpful.

Did you party after good results?

Kenny liked many things about Italy. The wine, for example. And also the opera music. On Sunday nights, if the race went well, we would all go to a restaurant to celebrate, about 30 people. In turn, we had to stand up and say or do something. In my case, I often sang some opera songs. Luciano Pavarotti, one of the most celebrated tenors, was from my same city, Modena.

You worked with prestigious former riders such as Roberts and 15-time world champion Giacomo Agostini, who were both your team managers, in different periods. Did you learn a lot from them?

Yes, all sort of things. They were legends. I must say that I made them go nuts, sometimes. When things didn’t go as expected, I would easily be in a bad mood. I would disconnect completely, stay on my own and be unreachable.

Did any of your opponents teach you something?

I must say that Toni Mang gave me a precious lesson when I was a rookie in the 250 class. In 1987 I had many races in which I felt super good with the bike and was really fast. In Sweden, for example, I remember being able to make many overtakes on the outside.

I was 24, while Mang was almost 15 years older. I was behind him and thought: he’s slow! So I overtook him and thought I was going to gap him. Well, that was not the case. In the last lap he passed me and closed all the doors, beating me for the win for less than three tenths of a second. That day I learned that there was no point in riding always at 100 percent, at the limit in every braking and every corner. Strategy was important. I never forgot it since.

Interview Jeffrey Zani + Photography Gold&Goose