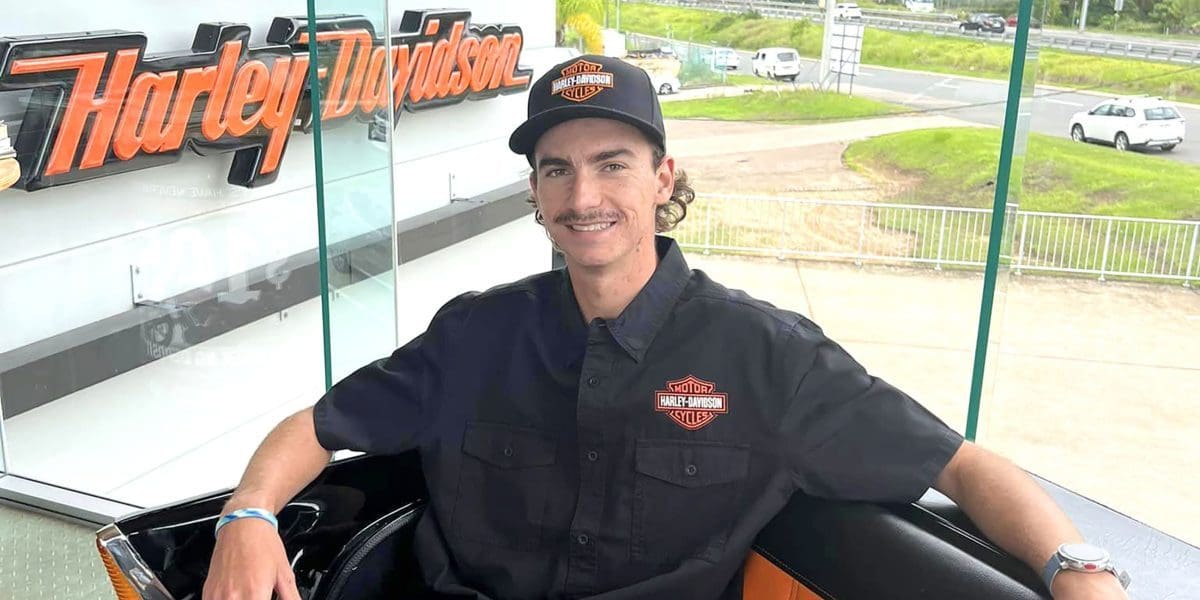

Over the course of a 40-minute conversation, you’d be hard pressed to know Senna Agius is still in his teens. Fully engaged, forthright and completely self-assured, he carries the air of an athlete who has a lifetime of experience behind him, rather than just his 18 years. That’s one of the many reasons the rider from Camden, south west of Sydney, is destined for big things.

After just three and a half years of living and competing in Europe, Agius is nailed on to win the European Moto2 Championship, triumphing in five of the six races he’s competed in to date. He has already impressed a host of world championship bosses thanks to an impressive string of replacement rides both last year and this. And Senna’s pinning his hopes on gaining a seat in the world championship for 2024.

It’s been a rapid rise for a rider who only switched from riding on the dirt for bitumen at the age of 11. Thanks to growing up on 100 acres (40ha) of land, where he could spend his junior days honing his craft riding motocross and flat track, Senna felt at home on the dirt. He racked up 17 Australian flat track titles in his youth before he followed brother Joel Taylor – a wildcard at the 125cc 2010 Australian GP no less – onto the asphalt for the first time. From there, “I didn’t want to ride anything else,” he said.

Reaching the grand prix world championship was always the aim. And after stints in the Asia Talent Cup, the Australian Supersport 300cc class and the all-Japan Championship, Senna moved to Europe with dad Jonathan in 2020 before competing in the FIM JuniorGP series, the feeder class for the Moto3 World Championship.

Results weren’t always straightforward. But a step up to Moto2 machinery in 2022 almost instantly paid off. Such was his speed in the European Moto2 series, he was handed the chance of a lifetime midway through that year: four rides deputising for the injured Sam Lowes in the vastly successful Marc VDS team in the Moto2 World Championship.

A whirlwind year also included an impressive sixth in an Australian junior cycling championship in the Australian summer, as well as an eye-catching second in the Australian Superbike finale at The Bend, where, on a Honda CBR1000RR-R SP Fireblade he finished ahead of the vastly experienced Wayne Maxwell and Jack Miller.

When AMCN caught up with Senna he was still recovering from a hand fracture that kept him out of the recent European Moto2 double header in Barcelona, where he could have sealed the title.

“The motion and mobility are all good. It was just something a bit out of character. I haven’t had many dismounts this year but you’re only going to get away with that for so long. But here we are, on the backside of it so all good.”

Can we infer from your first name that you grew up in a motorsport family?

Yeah. Growing up my dad was a complete fan. But my grandparents weren’t so it was completely forbidden for him. Once he put his big boy pants on and moved out of the house, he started doing it himself. When he was in his mid-20s he started working in a bike shop but it was obviously far too late to make it happen.

The late, great Ayrton Senna was definitely his idol growing up. It wasn’t just because he was his favourite driver and had a cool name; he really liked the mentality and technical ability behind Ayrton. It took a bit of convincing of mum to get the name across but it’s super rare. I can count one on hand the people I know with the name so it’s quite cool.

You grew up around Camden, just outside Sydney. Was this a perfect place to pursue the dream of being a motorcycle racer?

We are living on around 100 acres. So, I could have a bit of a playground inland while not being so far from suburban places. From around six to 10 years old I was a motocrosser. We moved onto a farm with a motocross track. I was racing for KTM in the national motocross championship at the time. I was going to be a motocrosser, was totally in love with it and then a few things happened. [I had] a few injuries and [saw] what my brother was doing at the time. I wanted to try road racing. As soon as I did it, it was like flicking a light switch over to the bitumen.

How has ex-Aussie racer Tony Hatton influenced your career?

He was the first Australian to win the Suzuka 8 Hour and he raced for Moriwaki for many years. He is like a massive part of my life. He helped me from the beginning and was like a grandfather figure at the racetrack. He started doing some engine maintenance for some of our racebikes. At first, he was just a guy that rebuilt my engines. But then he started taking an interest and then he started coaching. He still rings me the Monday after every race and tells me 10 to 15 million different things he’s seen from the TV. He even wants to know about setup. Sometimes I’m like, I can’t tell you as I’m not asking every bit of geometry about my bike! He’s so technical and so involved in the sport still from a distance, it’s nice.

You raced in the Asia Talent Cup at just 12 years of age. How was that first experience of racing abroad?

Looking back now it was a very fast progression and I think I paid for that later on. I was 11 at the tryouts coming from not riding on anything bigger than a kart track – with the age restriction in Australia you can’t ride on a GP track without a roadbike licence. We saw the Asia Talent Cup as a possibility. We went to the tryout in Malaysia at 11 – it was all so new. I crashed in the middle of the selection event and broke my collarbone.

We went to the hospital and I was devastated I wasn’t going to get selected but we got a phone call that night saying I had been. The next March we went to Qatar for Round 1. To go to a country like that with a completely different culture, in front of MotoGP was like the biggest experience of my life at that point, 100 percent. My first round at the ATC was my best one – I came sixth in Race 2 in Qatar. Then I struggled in some other races. I missed two races in the middle of the season. So I didn’t get invited back in 2019, which was hard for me to accept.

After that you raced in Japan in 2019. Was that a formative experience?

After 2018 we just went back home. We didn’t have many ideas for 2019. We didn’t really want to race in Australia because the only racing available at the time was production racing. We wanted to go the GP route. From the beginning ‘Hatto’ said the goal is GP bikes. He pulled some strings and got an old contact in the Moriwaki family and organised for me to be a Moto3 rider in the All-Japan championship.

The level was really, really high and I spent all of ’19 racing in Japan. That was amazing as I got to experience so much cultural stuff. I got to grow up really fast. I would leave school on Thursday afternoon, catch a flight from Sydney to Osaka or Nagoya. Land Friday morning and go to the track. Then I’d ride Saturday, Sunday. Get home Tuesday morning and go straight to my house, pick up my bag and go to school.

I was just on a completely different planet at that point to my friends in year seven. That was the first year I started getting some good results and training became a part of it. I lost a big part of my social life when I started doing that.

You raced a proper Moto3 machine for the first time in 2020, in the FIM JuniorGP World Championship and moved to Europe. How was that transition?

We had an apartment in Valencia. We had two coaches – a physical coach and a riding coach for 2020. I was riding for SIC58 Corse, Paolo Simoncelli’s junior team in 2020. I went from an ETC bike to a standard Moto3 bike. It was honestly huge, the level jump. I wasn’t really ready for it at the beginning. I was quite slow and took a long time to adjust. But I started to progress through the year. I hit a wall at the end of 2020 and didn’t really get what I wanted the following year.

I went back with some better training under my belt and did a second year with SIC58. I changed coaches at that point to Steph Redman, who is my current coach. Steph’s been with me for the past two years. I got some better results in ’21 and made a clear step forward. But the level was also super high. I was racing (Diogo) Moreira, (Dani) Holgado, (Izan) Guevara, (Ivan) Ortola… names that are now at the front of the world championship. It was definitely cut out for me that year.

How did you find racing for Paolo Simoncelli? Aside from not speaking English, he isn’t afraid to lay the boot into his riders if he feels it’s necessary…

Definitely when it’s deserved, he sees no harm in telling you how it is. I didn’t mind it. If you show you’re listening, and from that moment you show a change that he suggested, then he’s so happy. Because he can’t speak English, it’s always through a third person. It’s an effort to give some constructive feedback. When a rider doesn’t do it or listen, then that’s when he isn’t afraid to tell you what he’s thinking. I also think he was a bit more lenient on us than his world championship guys because the world championship guys were there for more than three years each. He knew we were all young and just coming to Europe. He’s coming from a good place. Also, from what that family has been through, the emotional side is quite hard in that team. I’ll be forever thankful for it.

How did you decide to switch to Moto2 machinery?

I was edging on six foot at the end of 2021 and I didn’t get any better than a top 12 (in JuniorGP). And I spent two years there. That’s when at the end of ’21 we signed with Promoracing, Raúl Jara’s team for the European Moto2 Championship. I remember my first session on a Moto2 bike and I was completely blown away. And this was on a Honda – the lesser man’s version of the Triumph we’re on now. I dedicated two years to try and get to the front of (JuniorGP) and I didn’t quite get there. I wanted to do a third year to prove to myself that I could do it. But a lot of people had to twist my arm to change onto a bigger bike and possibly step out of that world championship. I definitely felt like I was finishing something I didn’t achieve and it didn’t sit well with me. But looking at the situation I’m in now I’m glad I listened to the people around me.

The 2022 season was your breakout year. You shot to attention when you won both European Moto2 races in Barcelona. Was it a massive relief to win there, and prove to yourself you had what it takes?

One hundred percent. I’m kind of reliving it now that you’ve said it! I was quite humbled by the situation. But immediately, and this is something I’ve been told I unconsciously do and have worked on – I was really happy that I won but I was so focused that there was a race that afternoon. Then when I won that one, I was thinking there was another race in two weeks. I just had to be pulled away to understand what I did and then be happy.

I remember we went out for dinner on the Tuesday night (after the race) when my mum was here. That’s when I was like even happier than in parc fermé. That part of me of always wanting to do better, I was thinking I was only 30 points behind (Lukas) Tulovic (eventual 2022 European champion). If I could learn what I’d unlocked, maybe I could be in the championship fight. It definitely took some experienced people to grab me and say: ‘Mate, you need to be happy with what you’ve just achieved and switch off.’ But that’s just another personality trait of mine. Reflecting on the win [now] it was huge.

Your rides for Marc VDS in the world championship really put you on the map. You also progressed rapidly, finishing ninth in just your fourth race. How did that happen?

One hundred percent, the highlight of my career to date [is] when I got my first top 10 in the world championship at Valencia. Also, the professional side of being involved in one of the best Moto2 teams on the grid.

That first race in Austria I felt like a little kid at school. I made a constant progression and learnt so much working with someone like Gilles (Bigot, crew chief). I was so nervous. At the beginning I felt like I didn’t belong there but I knew I wouldn’t have got the opportunity if that was the case. So definitely when I got over the nerves and rolled out of pitlane next to guys I’d been watching on TV for the past 10 years, it wasn’t something that was very easy to see as normal. When I got over that, I got stuck in and understood where I was. That first weekend in Austria was a massive eye opener. But it was a breath of fresh air for them working with me being young – and I just loved it. I learnt a lot of things. When I went back to the CEV I was a different rider in terms of how I worked, understood the bike, and rode.

I heard you say you beat yourself up quite a bit when results didn’t come when you rode when you were younger. How have you learnt to deal with that?

It’s definitely better than what it was. But it’s something that’s ingrained in my DNA and I’ve learned to accept it. Nowadays I’ve got more skills mentally to channel it. But I’ll never lose that anger toward a situation. It’s an anger that comes from believing I can do something better. But now I can just understand that a bit more, and keep it within me. Before I was emotional, my emotions were affected and then obviously the information I gave to the team becomes affected and you become flustered. But now when I know I’m underperforming, I can focus on what I think is missing. Whether it’s the feedback I’m giving toward the setup or my riding. Nowadays you need to be mentally strong so that includes mental training. You have to be physically fit. And you have to make sure you’re good enough to race with the best in the world. Things have definitely progressed but I think that’s what’s needed to be in the world championship.

You’re managed by Leon Camier and train with him and the likes of Chaz Davies in Andorra. How valuable is it to be surrounded by that level of experience?

I really enjoy where I am at the moment and who I’m around. That’s a massive part of it and I learn from people that want the best for you at all times. It’s very important and I’ve got that now with Leon, my manager. He’s like an older brother to me. We can go hang out and we don’t need to speak about motorbikes one bit. Chaz and the different boys here in Andorra work in different disciplines and they’re all the best in the world at something. It’s quite nice to hear their journeys because they’re all ahead of me. Guys like John McPhee are still racing. Jules Cluzel has just retired. Chaz and Leon have retired. Even some of the rally guys like Adrien van Beveren and Sam Sunderland are there and coming toward the end of their careers. They see me as just beginning. It’s like a breath of fresh air for them and I can understand how they tackle different challenges in their career. And also just to be mates outside of racing – I’m really grateful for that.

What are your plans for 2024?

It’s no secret that I want to be in the world championship next year. We’re in discussions now. Nothing’s concrete so I don’t have much to report on that front. But my intention is to absolutely be there, 100 percent. Hopefully a few things play my way in the next couple of weeks and let’s see what happens.

Interview Neil Morrison + Photography Gold&Goose