Suzuki’s 2013 turbocharged Recursion concept bike will become the template for a range of boosted machines in the firm’s future line-up. We could see the first production fruit of forced-induction before the end of this year, but while the Recursion will be heavily influential, the concept bike won’t turn up in showrooms as is.

Ever since the Recursion’s first unveiling at the Tokyo Motor Show in 2013 it’s been a hot topic. A constant stream of patents over the months and years after it was shown revealed it was far more engineered than the average, purely cosmetic, concept bike. Details including its engine design and the layout of its turbocharging system and intercooler were all subject to patents, but despite that, those are among the elements set to change before we see it in showrooms.

Suzuki insiders have now told AMCN that while we will see a turbocharged, twin-cylinder production bike in the near future, it won’t use the Recursion’s 588cc, single-overhead-cam engine design. Instead the first forced induction Suzuki since the 1980s’ XN85 will use the XE7 engine that sat almost unnoticed on the firm’s stand at the recent Tokyo Motor Show.

While still a parallel twin around 600cc, the XE7 shares little with the Recursion’s engine.

Suzuki’s man explained: “We have changed other elements when taking into consideration it being used for mass production units as well as for various types of the bikes. For example, although it was a SOHC engine with two valves per cylinder for the Recursion, the new engine has been developed with DOHC and four valves per cylinder.”

As well as its different cylinder head design, the XE7’s turbo layout is new as well.

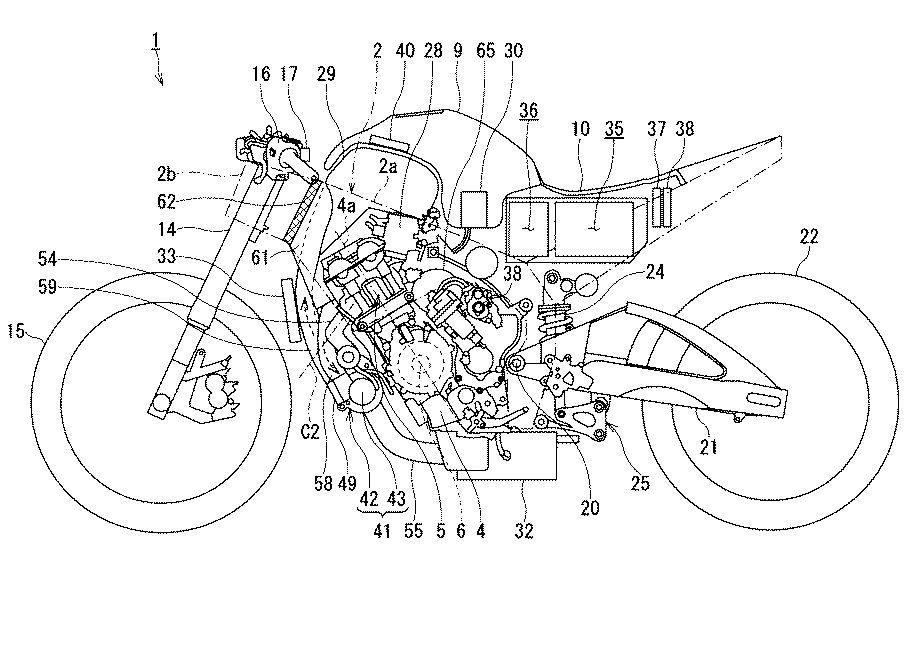

While the Recursion concentrated on repackaging the entire motorcycle around the turbocharged engine, the XE7 approaches the problem from the opposite direction, squeezing all the forced-induction componentry into a unit that’s much the same shape and size as a conventional, naturally-aspirated engine.

Repacking the entire bike around the turbocharged engine poses huge problems from an R&D and manufacturing perspective. Each newly-developed element had the potential to throw up unexpected hitches, delays or problems, and meant if Suzuki wanted to transfer the technology to models in different categories each one would need to be a clean-sheet design.

The XE7’s approach presents itself far more easily to mass production.

That brings us to the second element of Suzuki’s plan; the turbo engine isn’t destined simply for one new bike. Eventually, the firm envisages an entire range of models, spanning several categories and all fitted with the same turbocharged engine. Few firms build engines dedicated to a lone model, and this is no exception.

“We are continuing development with a view to using turbo technology in production machines in the future,” Suzuki’s man said.

DEVELOPING SIMPLICITY

According to AMCN’s Suzuki insider, “It quickly became apparent there was a demand to see a mass produced version of the Recursion’s turbo technology, and this led to further development of the engine.” Here’s a quick look at how they achieved it.

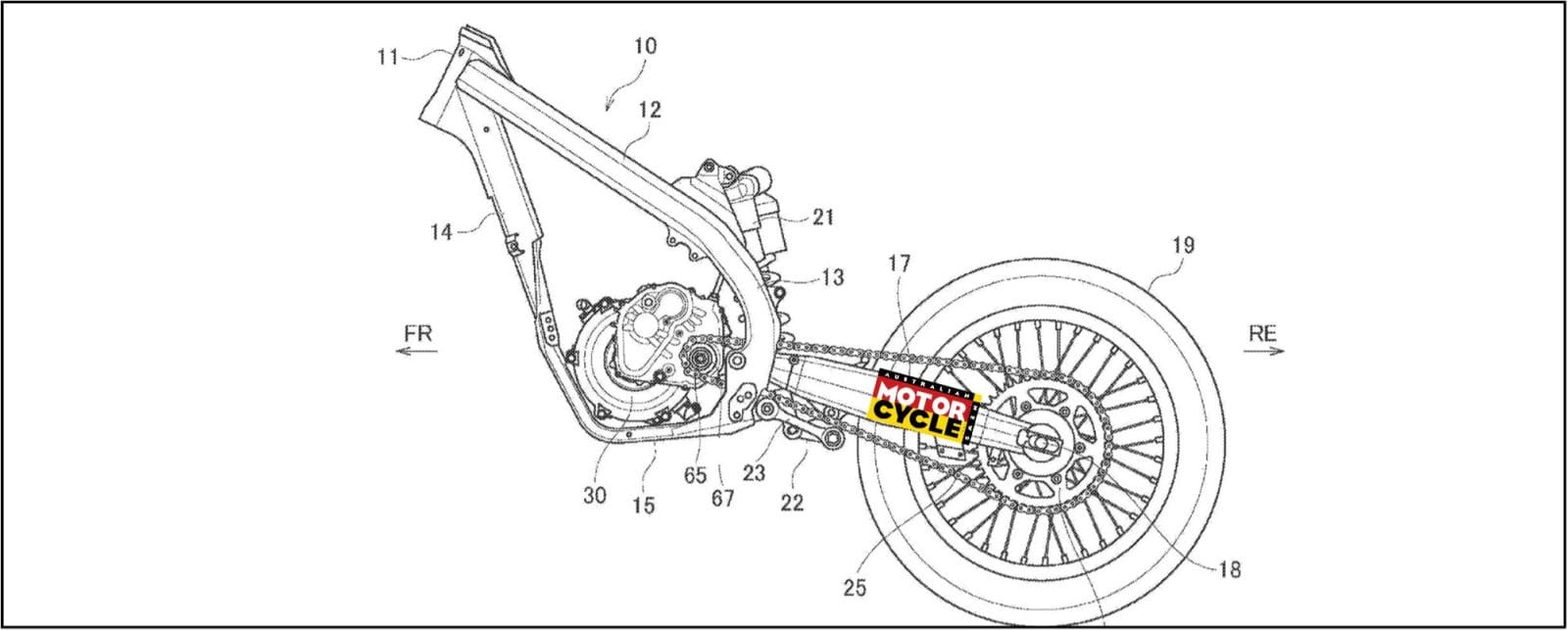

Recursion Engine

The Recursion drew its intake air from an air filter mounted near the rider’s left foot, sucking it into a turbocharger hidden in the belly pan. The air was then compressed and sent to an intercooler under the rider’s seat which was chilled by fresh air ducted through the headstock. It was a well-thought-out design, but one which required the whole bike to be developed from scratch around the turbo engine.

XE7 Engine

The overall shape and size of the engine is much the same as a conventional parallel twin. The air filter is mounted above the cylinder head. The intercooler and pressurised plenum chamber are mounted alongside it in the same spot and the whole lot is no larger than a normal airbox. The turbocharger is tight against the front of the and attached to the shortest exhaust headers – a change that should reduce turbo lag, too.

PERFORMANCE?

Suzuki has been open about its turbocharging plans but actual details of the XE7 engine are still shrouded in secrecy. For the SOHC two-valves-per-cylinder 588cc Recursion, Suzuki claimed 75kW (100hp) at 8000rpm and a superbike-sized 100Nm of torque at just 4500rpm. Indications were it was a low-revving engine tuned for grunt rather than power, with economy also high on the list of priorities.

The XE7, with twin cams and four-valves-per-cylinder, is more like a modern normally-aspirated engine in its design, suggesting it’s intended to reach higher revs (the four-valve layout reduces reciprocating mass, allowing more revs).

Indications are the turbo will be a low-pressure one, designed to minimise lag and give a spread of power rather than massive levels of boost. It will also allow the engine to have a higher compression ratio, so the off-boost performance isn’t lethargic.

If, as suspected, the engine is around 600 or 650cc, a light-boost turbo would probably increase performance to 750cc-1000cc levels.

WHY TURBO?

Turbos in the 21st-century form have allowed small-capacity cars to produce impressive power while also returning impressive economy and low emissions. In blunt terms, the turbo increases the effective capacity of an engine, compressing intake air before it even reaches the cylinder so a small-capacity engine can, when required, burn as much air and fuel in a single cycle as a larger naturally-aspirated engine would. The turbo is driven by waste exhaust energy and doesn’t sap power as it goes about its business.

But unlike a large normally-aspirated engine a turbocharged tiddler can revert to its frugal, small-capacity levels of economy and emissions. On a part-closed throttle, a big engine is wasting energy trying to suck air through that small remaining opening into its massive cylinders, resulting in so-called pumping losses that are the enemy of attempt to make engines economical.

THE FOUR CYLINDER?

The twin-cylinder XE7 might be the first turbo Suzuki we see but the firm has also been working on a much higher performance four-cylinder design. Patents revealed last year showed Suzuki is researching a large-capacity inline four with a turbocharger mounted at the front, much like a double-sized version of the XE7. The patents also showed the bike is being developed with an electrically-assisted turbocharger, borrowing the idea from the latest F1 cars. An electric motor would spin the turbo up to speed to eliminate lag, while also acting as a generator to recover electricity when the turbo needs to be slowed.

Some have speculated that the bigger turbo Suzuki will be the basis of the next Hayabusa, but insiders have hinted it’s unlikely, with the next-gen version of the firm’s hyperbike expected to retain a large, naturally-aspirated four-cylinder engine. For the generation after that, in perhaps a decade’s time, a turbo might make sense.

THE PAST

We’ve not seen a turbocharged production bike in decades but the new Suzuki won’t be the first boosted machine to carry the firm’s name. The XN85 of 1983 was Suzuki’s effort in the brief turbo bike era of the 1980s.

The XN85 was derived from the existing GS650 engine, modified to 673cc and given a chain drive instead of a shaft. A modest level of boost meant that peak power was 85hp – giving the bike its name.

As with the other turbo bikes of the era, Honda’s CX650 Turbo, Yamaha’s XJ650 Turbo and Kawasaki’s GPz750 Turbo, it turned out to be a short-lived machine, with few riders seeing a benefit to turbocharging. Now, with far better technology and a greater pressure to create fast, economical and environmentally aware bikes, the turbo might finally have the success it failed to achieve 30 years ago.

by Ben Purvis