I’stut-tut! The word is Zulu, and means motorcycle. Anybody reared on a diet of modern multis would immediately understand why, if they came anywhere near the Durban to Johannesburg Rally. It is exactly the sound emitted by a 1930s Velocette. Or BSA, Norton or Triumph etc, as long as they have only one cylinder.

DJ stands for Durban to Johannesburg, and the annual rally commemorates a completely crazy 400-mile public roads race, that ran from 1913 until 1936, until finally sanity prevailed, in the form of state intervention.

But the DJ was not to be forgotten.

In 1970 the event was revived as a regularity rally rather than a flat-out blinder, but open only to bikes that would have been eligible for the real thing … in other words built before the end of 1936.

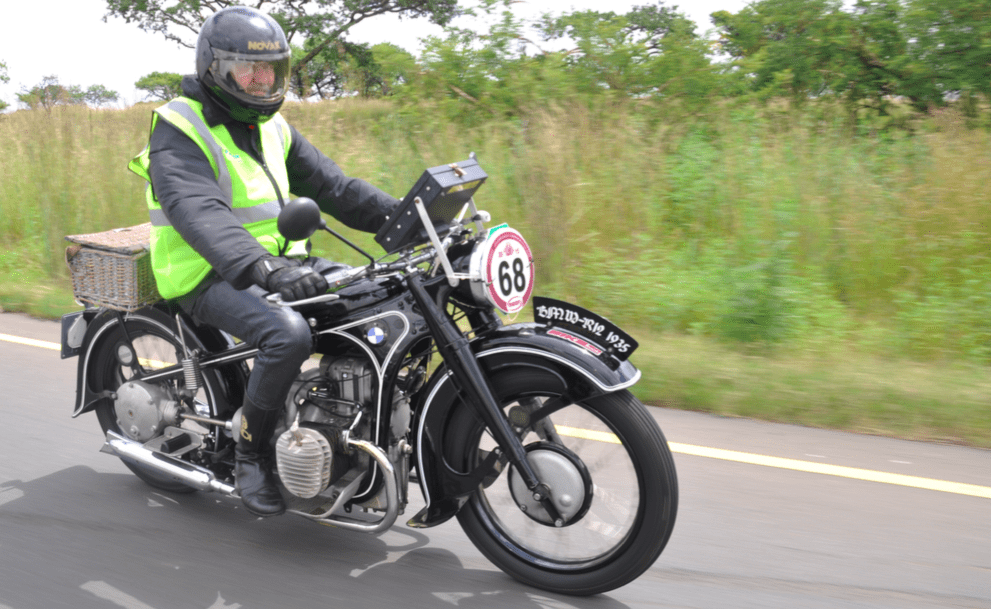

My steed was a 1935 BMW R12, a side-valve 750 flat twin, and my participation was all thanks to Simon Fourie – philosopher, philanthropist, flat-out merchant and old friend. Fourie is a major figure in South African motorcycling, still racing himself at 70, and is editor/publisher of the seriously unique Bike SA magazine.

He is famous for all sorts of reasons. One was the time he used his K0 Honda 750’s sneaky electric starter to beat the visiting Giacomo Agostini’s factory MV Agusta into the first corner at Roy Hesketh circuit, only to spoil it by running straight on. Another is for entering the gruelling dirt roads Roof of Africa marathon (across the mountains of Lesotho) on the same completely unsuitable machine. He almost completed the first of two days before collapsing exhausted in the middle of the road.

This year, however, he decided not to ride in the DJ. Instead, as we ex-changed emails, he said: “Wanna ride me bike?”

No second invitation was necessary.

The BMW R12 is a classic version of the air-cooled flat-twin breed, and one of the bikes that helped Hitler lose the war – though not through any shortcomings of its own. It’s worth recording that three BMWs entered the DJ: another side-valve R12, and the much more exotic twin-cam overhead-valve R5. And three BMWs finished it. The same could not be said for 26 other machines of the 100 starters.

I know of no other event in the world that better celebrates old motorcycles than the DJ, or that tests them harder. The London-Brighton run is admittedly for much older bikes (and cars), but it’s only 80-odd kilometres, and all you have to do is get there.

In the DJ, it’s around 400 miles, and complicated by the need to stick to an exact time schedule past hidden control points, over several extended regularity sections with varied average speeds.

With bikes starting at one minute intervals, and in different speed groups, so you can’t use anybody else as a marker, either. I’d chosen to be in the 60 km/h group, on the grounds that means one kilometre a minute. Didn’t help much – speeds over five timed sections on the first day varied from 25 km/h to 60, and all points between.

As a rally virgin, my first aim was just to get to the end. But there were certain tips to follow. Like counting the white lines.

I had two stopwatches on my rally dash, beneath the roller strip with the pace notes, on a box that conceals the speedo. Should have been three, but I lost one at the crucial time. One you set going as you are counted off at the start, and try to match it to the pace notes, which display cumulative time each day. The other is spare, for things like counting those white lines. Which I did assiduously for a while only to find I was getting so far ahead of the pace notes that they quite ceased to make any sense. I later learned that in the new South Africa such logic no longer prevails in the road markings.

Nor do the pace notes help much. Legends of marker points are few and far between on the timed sections; and the landmarks wilfully vague. For example: “Bridge”. Or “Overhead wires”. Or “Tree”. I was passing through a forest the first time it suggested I should be ticking that one off.

I’d met the bike the day before. A beautiful low-slung hunk of gleaming black enamel and white pinstripes, with flared mudguards, footboards and a heel-operated rear brake. A pioneering telescopic front fork provided some suspension at that end, while a large sprung seat insulated the rider from the pain felt by the hardtail rear. A pressed-steel frame kept the wheels apart; levers projecting from the bar ends operated the clutch and (rather notional) front brake in the normal way, the layout not only keeping cables tucked out of site within the bars, but providing better leverage, with the stronger fingers having the greatest mechanical advantage.

The major difference from a modern was the four-speed gear change, operated with a car-style H-pattern (first to the left and down, and so on).

Fuel on, tickle the carb, and it’s an easy sideways kickstart, settling to a chuffing idle. Time for a brief test ride in the Jo’burg ’burbs. My apprehensions about the gearchange proved ill-founded. The four-speeder was easy to operate, though slow and inevitably clunky on downshifts: with your right hand off the throttle, you can’t blip. As Gawie Nienaber, riding the other R12, explained: “At least you know you’re in gear.”

The problems lay elsewhere: I was unable to keep pace with Fourie on the escort scooter, who planned to indicate the speeds to me (30, 40, 50 km/h) so I could familiarise myself with the beat. Soon the R12 stopped altogether – it was completely flooded. The test ride was abandoned for a trip to the workshop. Rather worryingly, no faults were found, but the carb was cleaned and the float valve resettled. Hope for the best … I eventually if belatedly discovered that creative use of the advance-retard lever on the left bar was of great remedial value.

But I was yet to learn this (silly vintage virgin) as I lined up for the start at 06.08 two days later. We’d been up at 05.00 to truck the bike down the day before, and at scrutineering in an underground carpark I’d acquainted myself with my rivals.

Bike-wise, it was a nostalgic dazzle. There were 26 different makes, mainly British and mostly singles … easier to estimate your speed when you can count the beats. Most numerous were BSA, Velocette, Ariel and Sunbeam, in that order, and between them making up almost half the entry. Norton, Triumph and AJS were strongly represented; handfuls of Royal Enfields, Panthers, Indians and Zeniths swelled the numbers. There were a couple of Harleys, and some real rarities, including a single Motosachoche and a New Henley among the remaining Rudges, Zündapps, OK Supremes and Matchlesses etc. And a gorgeous 1936 DKW 500 two-stroke twin, that suffered dynamo failure and failed to make it off the start line.

Oldest bike of all was a clutchless pedal-operated single-gear belt-drive 1909 Humber, ridden by plucky Samantha Anderson, who had taken up mountain biking to get fit enough to help it up the hills.

And the competitors? A gathering of granddads, leavened by a smattering of youngsters, including one 23-year-old. The oldest rider was one Henry Kirton, who at a very chipper 82 had yet to turn three when his 1930 Ariel left the production line. He finished 54th. It was company in which – in my advancing years, and along with Cal Crutchlow’s dad Dek – I could feel comfortable, and even sprightly. Adventure before dementia. You know it makes sense.

The rally starts some 30 kilometres inland from Durban, where it becomes convenient to join the Old Main Road, and follow the authentic route. Back when it first started it was mainly a very rudimentary dirt track, including farm gates and stream crossings; now it is (in many stretches) a deteriorating secondary road long since replaced by freeways. While on day two in Gauteng Province (the former Transvaal), long stretches feature extensive stop-and-go sections where only one-way traffic is allowed, entailing waits of up to 20 minutes. This forced the organisers to abandon some previously timed sections, but gave overstressed old engines and riders a chance to get their breath back, in time for the next session of kick-starting.

The rally started in light rain as we chugged up a serious of escarpments to finish 348km and more than nine hours later in Newcastle, with a couple of stops for refreshment. Long before arrival it had turned blazing hot. Wearing leathers under full waterproofing, I was slow-cooked. Having lost touch with the pace-notes soon after the lunch stop, where my main stop-watch mysteriously zeroed itself, I was surprised to find myself placed 57th out of 100 entrants. Incentive to try a bit harder the next day, to get into the top half.

It rained in the early hours, but a brightening sky persuaded me to abandon my waterproofs, packed away in luggage carried by support crew Fourie and companion Sharon Kell. We had one more major escarpment to climb – past the famous Majuba Hill, scene of the decisive battle in the first Boer War, where the British were routed by commando-style troops in 1881. Beyond lay the Highveld, around 1820 metres high, where I reasoned that dry heat would be more of a problem than rain on the almost 320km run to Johannesburg. This proved a very foolish error.

The same start time, in the middle of a power cut – which caused one unfortunate to fall victim to a muddle at the inert traffic lights in a luckily not too serious collision.

For the rest, the beckoning vista of the Drakensberg mountains revealed ominous patches of mist clinging to the valleys, as we passed our indicated trees, bridges and overhead wires.

The rain began again on the climb past Majuba, but got really serious on the Highveld. Soon I was wet through, my sodden leather jacket weighing me down. I was freezing cold, teeth chattering, hypothermia threatening, and the support truck nowhere to be seen. Eventually we did hook up … luckily at the end of a timed section, although by then I cared little about regularity, and would willingly have lost the 15 minutes it took to get warm, waterproof clothes on.

Others were less lucky. At the next fuel stop, at Balfour, I watched a brave elderly man remove his boots, empty them of water, and wring out his sodden socks. A female spectator took pity. “You can’t put those back on,” she said. “Take my socks.” Which is why he ended up wearing pink hosiery from there on.

Long stop-and-go sections with generous time allowances meant I could catch up again, and on the last run into Johannesburg I was within 15 seconds of the final three targets. I was learning how … a little too late perhaps, but enough to elevate me to a reasonably satisfying 51st overall.

But in this company, 15 seconds is yawning gulf. For comparison, my total accumulated points were 2116. Winner Kevin Robertson has erred by a total of only 136 seconds, with fellow Velo rider Mike Ward a heart-breaking eight seconds off, and third-placed Martin Davis (Sunbeam) just ten away. The top 30 all accumulated less than 1000 points – they clearly knew what they were doing.

Bonhomie prevailed at the prize-giving at the Vintage and Veteran Club the next day. Anyone who got a finisher’s medal could be proud. In bad conditions on ancient motorbikes, getting to the end of this unique event was some sort of accomplishment. As unique in its way as the Isle of Man TT.

The DJ is not exactly under threat, but there are (as with the original race) growing murmurs of the danger, on a deteriorating road system with increasingly busy traffic, including some merciless taxi-buses and big trucks, which don’t pay much heed to slow-moving old motorcycles.

International support would do a lot to counter these arguments, which are clearly an anathema to every single participant. Got a pre-1936 bike? Got a good friend who can lend you one?

STORY MICHAEL SCOTT PHOTOGRAPHY