Is Ducati the new Honda?

Current events in MotoGP show a kinship that is both impressive and alarming. Along with a great and rather heart-warming reliance on having plenty of horsepower, there is a certain attitude. It is the creed that engineers are the most important part of the combination. Under the autocratic control of the gifted Gigi Dall’Igna, this has been heavily reinforced.

Enea Bastianini, MotoGP race, Qatar MotoGP, 6 March 2022

Enea Bastianini, MotoGP race, Qatar MotoGP, 6 March 2022

Rossi’s long-serving crew chief Jerry Burgess, a long-term fixture at Honda with Gardner, Doohan and Rossi, summed it up neatly: “For Honda, riders are like light bulbs. When one burns out, you screw in a new one.”

That attitude triggered Valentino’s turncoat departure to Yamaha at the end of 2003, taking Burgess and his mainly Antipodean gang with him. He was determined to prove that it was the rider that made the difference, not the bike. Four more championships proved his point.

Yet the opposite happened when he went to Ducati for two years. The bike ruled the results. And not in a good way. The Italian Stallions have been revitalised since those dark days. As well as being the most technically adventurous MotoGP bike, the Desmosedici is reliably the most powerful. Desmodromic valve gear is not just for bragging rights, you know. It cuts engine drag, and offers very precise and very rapid valve opening and closing, especially at high revs.

Ducati combines its enviable engine with a raft of innovations to the cycle parts. Ducati were the first with wings, and continue to set the pace with aerodynamics; the first with the “spoon” ahead of the rear wheel – nominally to cool the tyre, but also with aero benefits; and the first not only with shape-shifting launch control, but also to introduce it to both ends of the bike, and to allow riders to operate it during the race rather than just off the start line.

In every case rivals have tried to thwart them, then copied them … at least until this year, when protests forced a ban on “any device that modifies or adjusts the motorcycle’s front ride height while it is moving”.

Responding to the ban, sporting director Paolo Ciabatti made clear the company’s disappointment. The investment in time and money was “fully compatible with our budget. Some manufacturers spend high amounts on their riders. It’s up to them. But they should not criticise when we spend money on development.”

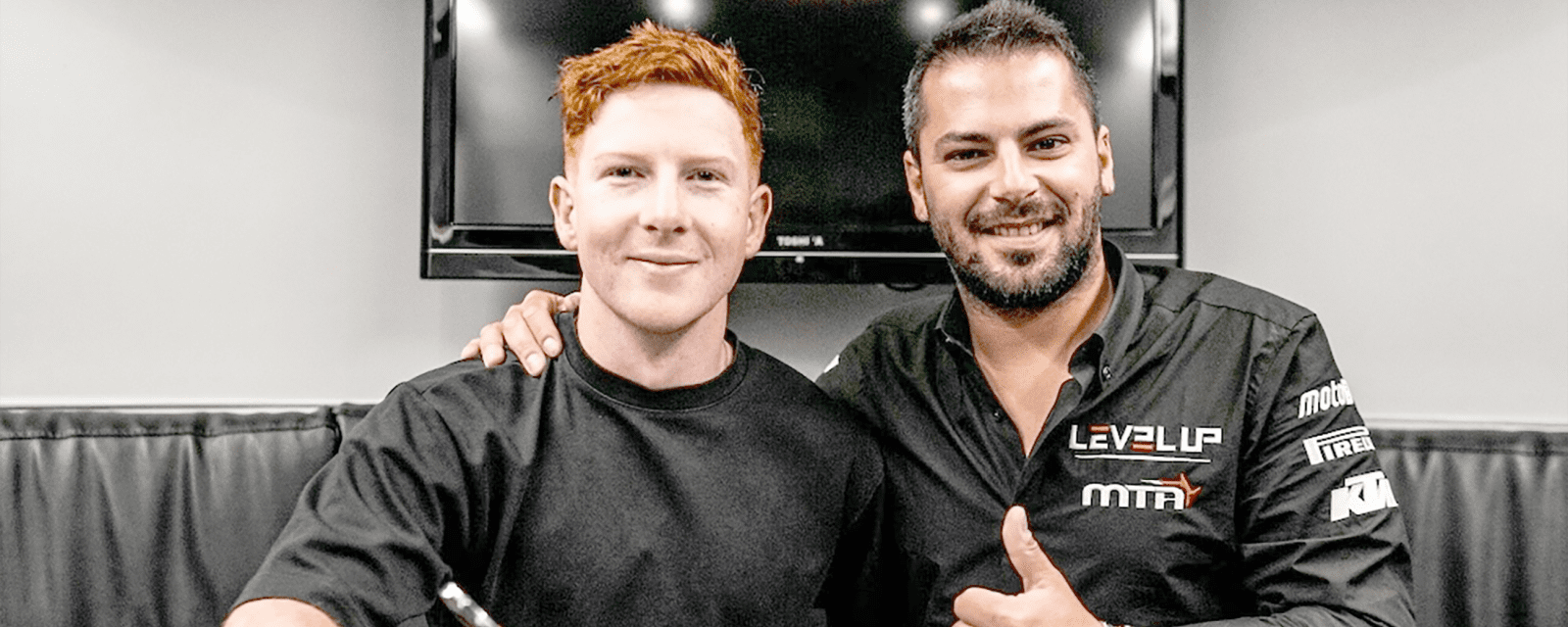

All this makes it very clear. Ducati’s main emphasis is on engineering. But back to the light bulbs. The Bologna firm has a dazzling array – eight riders is at least double any other constructor, and in the case of Suzuki and Aprilia four times as many.

Trouble is, almost all of them are 200-watters. Every Ducati rider has won at least one grand prix, and half of them premier-class races. Four of them – Bagnaia, Bastianini, Martin and Zarco – are former world champions. Small wonder that they take points away from one another at every race.

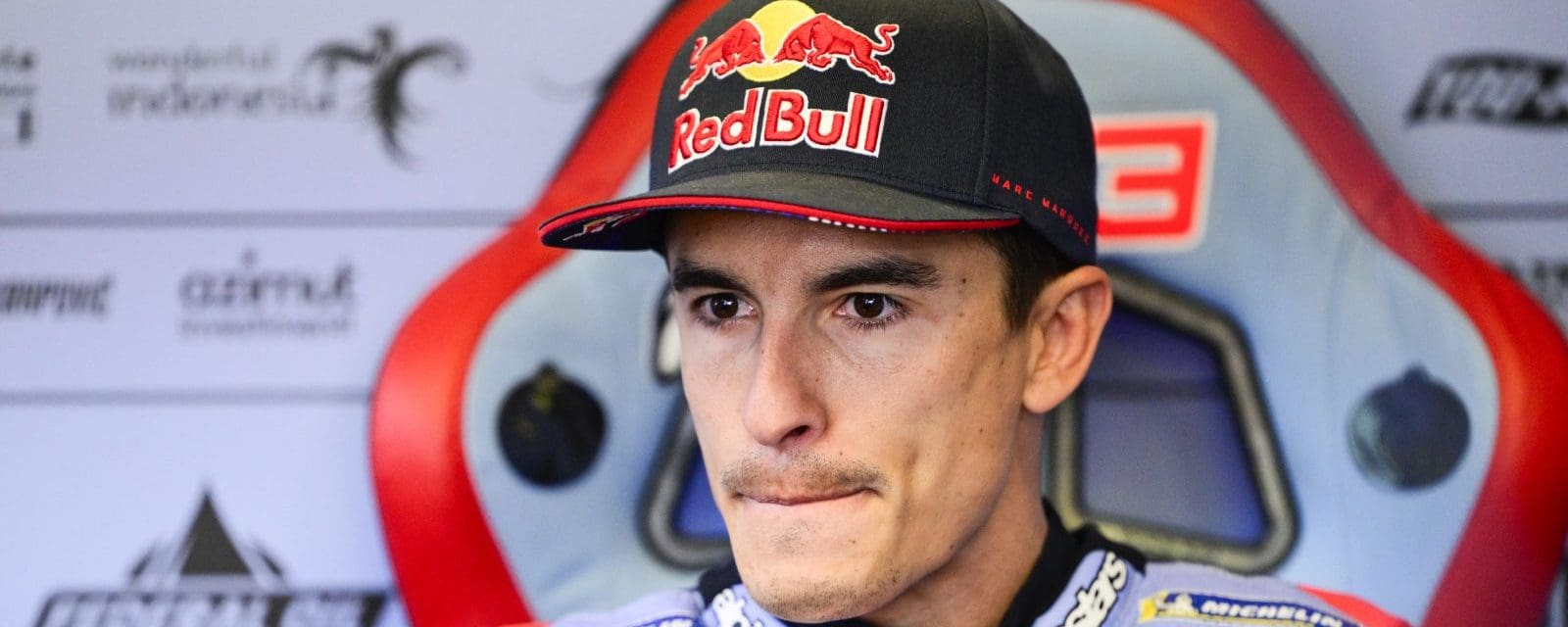

Seems that Honda may have played the light-bulb strategy better. By and large, at least since the long-distant days when Wayne Gardner and Eddie Lawson disputed the 1989 title on rival Rothmans-backed NSRs, it concentrates on just one very bright bulb and has won the majority of riders’ titles over the past four decades. Spencer, Doohan, Rossi, Marquez … a burning-bright array.

Then again, this has cost the factory dear for three seasons now. The absence of arc-lamp Marc Marquez meant a historic zero wins in 2020, only a handful in 2021, and a 2022 where the prospect of another winless season has been compounded by a German GP with not even a single point – a first since 1982.

Ducati’s light bulbs clearly undermine each others’ title chances. But the factory engineers can at least gloat about the near certainty of a third successive constructors’ crown.