Righto, let’s set the scene before we add the Salt. In the last couple of years, there have been a few bikes that get called ‘Australian made’. One comes from China complete and is rebadged here, the rest are customs with impressive dollar tags to match.

Then there’s the murky world of the cafe-racer scene. I say murky because as an old motorcyclist, it seems most of these ‘custom shops with a cafe bar’ put more engineering into their T-shirts than the bikes they so-called build. Time spent getting the seat right rather than working the fork and brakes. Like most people who rode through the 1970s, looking at a bike that was mundane rubbish in the day ‘customised’ into something that’s still rubbish can be hard to handle.

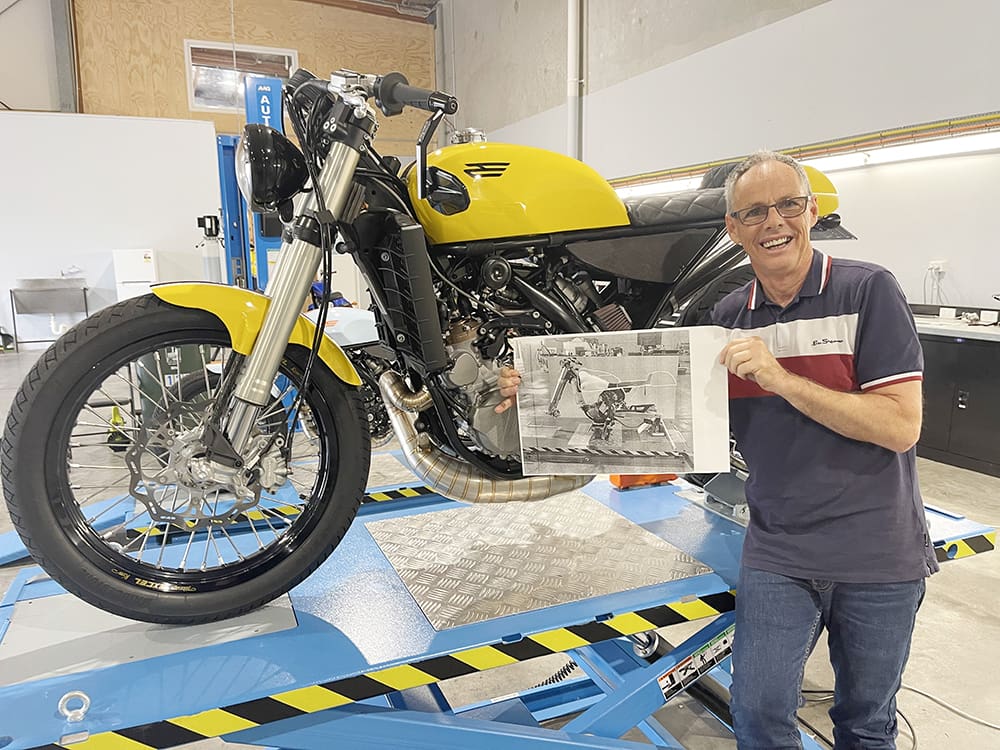

This is where Salt Motorcycles steps away from the crowd. Yes, they wanted cafe racer looks because well, who wouldn’t? But they wanted performance, they wanted technology that worked well, they wanted reliability and longevity and most of all, they wanted to build a rider’s bike that Australia could be proud of.

The result? World-class beautiful machinery. This is what happens when real motorcycle enthusiasts build a bike.

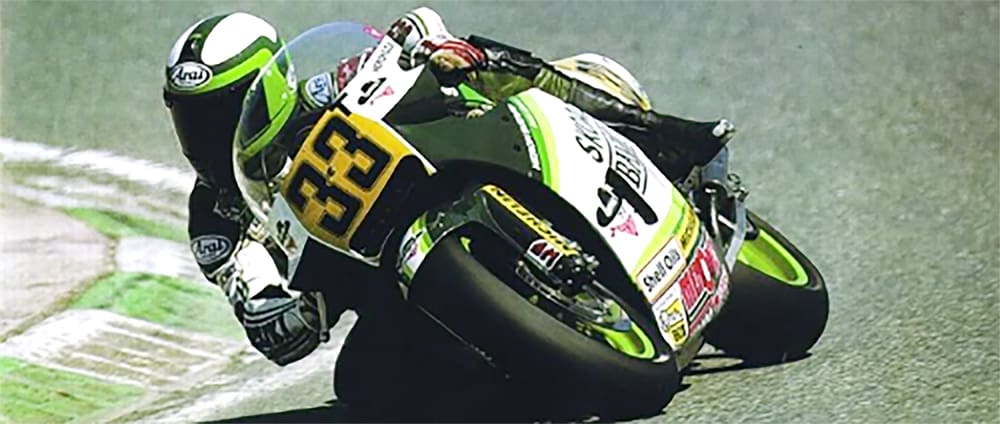

It started when former GP rider Paul ‘the Angry Ant’ Lewis was still managing Morgan & Wacker. One of his repeat customers was Brendan James, a motorcyclist who’s also a very successful mining engineer with a career in metallurgy and reprocessing old gold tailings. Brendan owned a few bikes – including a two-stroke, of course – but he’d had a hankering to build a real Australian bike. And after 10 years of punting the company Ultra Glide to work, Paul had had enough of retail.

As a teenager Lewis was fixing motorcycles in Altona, in Melbourne’s south-west. He was soon apprenticed as a mechanic but was too quick on a bike to not go racing. I saw him ride at Bathurst in the 1980s when he blew his bike up on a Saturday and had it completely rebuilt and ready to race by 3am Sunday morning. He might have taken speedway champion and mate Gary Flood to Europe as his mechanic, but it was usually Paul on the spanners. In fact the hardest thing for him when he graduated to a factory ride was to walk away and let the mechanics sort the bikes. He’d get back on the bike and think ‘did they bolt that caliper back on properly?’

Paul had always wanted to build his own motorcycle. He and Brendan got together.

Eventually, they’ll build a complete hydrogen-fuelled V8-engined motorcycle here in Australia, but to kick things off and build the Salt name for quality, they decided to start with something a bit less daunting. Like Paul said, “to build a bike from scratch with the V8 is going to take time, we wanted to get in and show what we could do.”

So after lots of research they settled on the most popular two-stroke on the market, KTM’s 300 EXC, the only registerable stroker with a balance shaft. The 300 is legendary in the world of enduro, which demands reliability as much as performance. It’s a top-quality machine with an abundance of parts available, a perfect starting point for a project like this.

But they wanted solid cafe racer looks, too. This is where things take a little sidestep because with the expertise on tap, it would have been easier to build a racebike. The Salt isn’t a road racer; it’s a cafe racer that goes, handles and stops like a racebike.

You can see that in the combination of 18- and 19-inch wheels. Sure, there are better wheel/tyre combos for racing, but you lose the look. Don’t worry, if you can’t go harder on this cafe racer than most blokes on their trackbikes, the problem isn’t the tyre size.

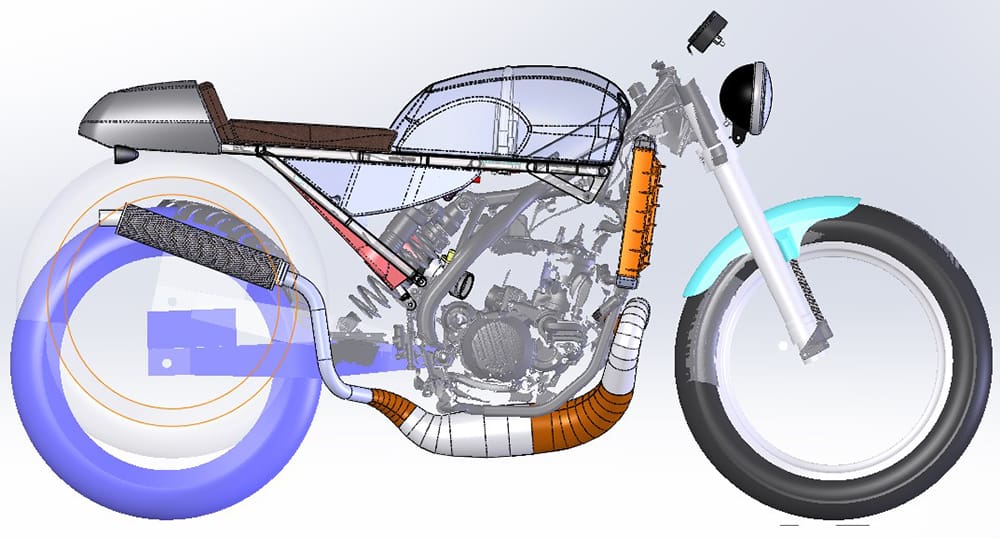

So a KTM was stripped and analysed. Common sense said to keep the standard cradle frame intact (no cutting or welding) but the aluminium subframe was binned and a new one engineered to suit. It’s integrated engineering though, with the frame scanned by Solid Works guru Stuart Black and all components computer engineered before being trialled in real life.

The swingarm is standard but whereas enduro bikes need a lot of droop to get traction in the dirt, that’s not necessary on the road. The WP suspension was modified to give 110mm of travel at the back and 112mm up front with re-valving handled by Paul Bearicke at MPE to Lewis’s specifications.

I’m going to say this once but put it on replay throughout this yarn. Nobody understands geometry, suspension, weight, strength and the interplay of same than a GP rider who’s done his own mechanic-ing. Nobody. And the attention to detail is next level.

Take the petrol tank. There are bucketloads of aftermarket cafe tanks out there but most of them are buckets at best. The KTM frame takes a plastic saddle bag tank, so Paul and the team had to start from scratch. They designed a shape they wanted with a 19-litre capacity on the computer and took their idea to John Cox on the Gold Coast. John’s the guy who’s famous for building all those Hollywood monsters before CGI took over and he’s got a huge CnC mill, so he machined a tank from foam using their file. Once happy with the shape, the team built a wooden buck to facilitate building tank panels with aluminium shaped on an English wheel. Those panels are welded to a base plate Paul designed that takes the fuel injection pump.

That folks is attention to detail. It’s also what you get when the emphasis is on nothing but the best. That’s what makes the Salt different; every component has been subjected to a design and construction regime to make it perfect. Look at that exhaust.

The best pipe for the KTM is acknowledged to be the DEP performance pipe. Unfortunately, unless you’re kicking dirt, it’s as ugly as Scomo in drag. But two-strokes demand perfection in expansion chamber design so Paul took a DEP pipe, scanned it, measured it and sliced it up on the computer. They worked out the volumes and straightened it out into a horizontal plane. That left them with a bunch of cone shapes and a huge problem. Who could roll cones like that?

Enter the Lewis factor again. There are a couple of expats in Thailand who specialise in this stuff but they were too busy to contemplate such a big job. At least they were until they found themselves talking racing with a legend.

Paul got them back, stuck them together with duct tape and spot welded up a system once the computer decided how it would best fit the bike. That then went back to Thailand for production. Lots of effort but the result is a work of art that actually performs better than the original.

Talking performance, the Lewis factor means the ECUs go to the best man in the business: Melbourne-based Dave – surname withheld so you don’t pester him – flashes the KTM ECU to give it more oil for longevity while ramping the fuel to allow for the higher-compression cylinder head. This wasn’t so much about compression as getting the squish right – more GP level tuning. Yes, the result is more power, everywhere, and the stock KTM wasn’t exactly a shy bike, to begin with.

The brakes are the standard KTM Brembos for a very simple reason: you couldn’t make them any better. Not so the gearing though. Paul settled on a 38-tooth rear sprocket to replace the KTM’s water-wheel sized thing and, once again, who knows gearing better than a GP rider?

Top shelf, eh? Like everything else here. The trailbike footpeg position was all wrong, so using the same formula – scanning, computer designing, 3D printing and modifying – Paul used the standard mounts to bolt on new lightweight ’pegs to suit road riding. Side panels, manifold, radiator guard, even the carbon-fibre front mudguard with its hidden mounting rods were all engineered to the same specifications: good looks, perfect fit, long lasting and all for the least weight possible.

The same thinking went into sourcing all the ancillaries and electricals. No plastic here – mo.lock key system, Moto Gadget electrics, aluminium button blocks from Estonia – the best stuff in the world. Not cheap, but really good.

However no amount of cleverness could get around the fact that the KTM gearbox doesn’t have a barber’s pole on the selector drum which means fitting a neutral light isn’t possible. Paul did his research and came up with the Rekluse clutch which, with some retuning, centrifugally locks in between 2500 and 3000rpm, perfect for the power delivery. That means a rider can pull up, trigger down the shifter to find first and then gun it to go. As a side benefit, it’s also a superb launch control. Just bang the throttle and go! But remember to hang on…

No two Salts will be the same. Why? Because when you put your order in, you’ll be asked what colours you want, how tall you are and er, how many pizzas you consume in one sitting. The team then mock up your bike on the computer until you’re happy with it and Paul himself tailors the seat height and suspension to suit you. The yellow one I rode was built for a short, aggressive person who weighed a whole lot less. I’m not good enough to know the difference, but I’m still smiling!

Okay, so for about $40k you can have a beautifully fast motorcycle built and tuned just for you by a former GP rider. Personally, I’m surprised they can do it for that kind of money. Add in the fact that this is arguably the best production motorcycle ever built in Australia, it’s bound to be a collector’s item in the future.

But true happiness comes from sprinting through a set of corners, swinging through the gears and keeping that stroker on song. Oooh, bloody marvellous, motorcycling mates.

Words John Rooth Photography David Cohen & John Downs