In 1972, bikies ran riot through a New Zealand city square in an event unlikely to ever be repeated

The roar of dozens of British motorcycles heralded an event that is still etched into the minds of police officers on duty in Palmerston North, New Zealand, on Easter Saturday 1972.

In his book of Manawatu police history Beyond the Call of Duty, the author Ray Carter wrote: “It would be without doubt the worst day Palmerston North has ever experienced.”

Back in 1972 Carter, although a police officer of seven years’ experience, was unprepared for the events that unfolded in front of him.

“I was totally overwhelmed by the mass of bikes and hardened-looking characters with their patches,” he told a reporter at the launch of his book in 2016.

Tension had been building for many months between the Mongrel Mob and bikers in the lower part of the North Island.

Over the previous few years an expansion of this mainly Maori youth street gang had seen it spread from the Hastings area all the way down to Wellington, New Zealand’s capital city.

In this time the outlaw-club culture in New Zealand had changed rapidly from the so-called ‘milkbar cowboys’ of the 60s to a more extreme, tougher version the news media called ‘bikies’.

What had started out as loose collections of motorcycle riders hanging out at corner stores and cafes on Friday nights had become a dedicated lifestyle choice.

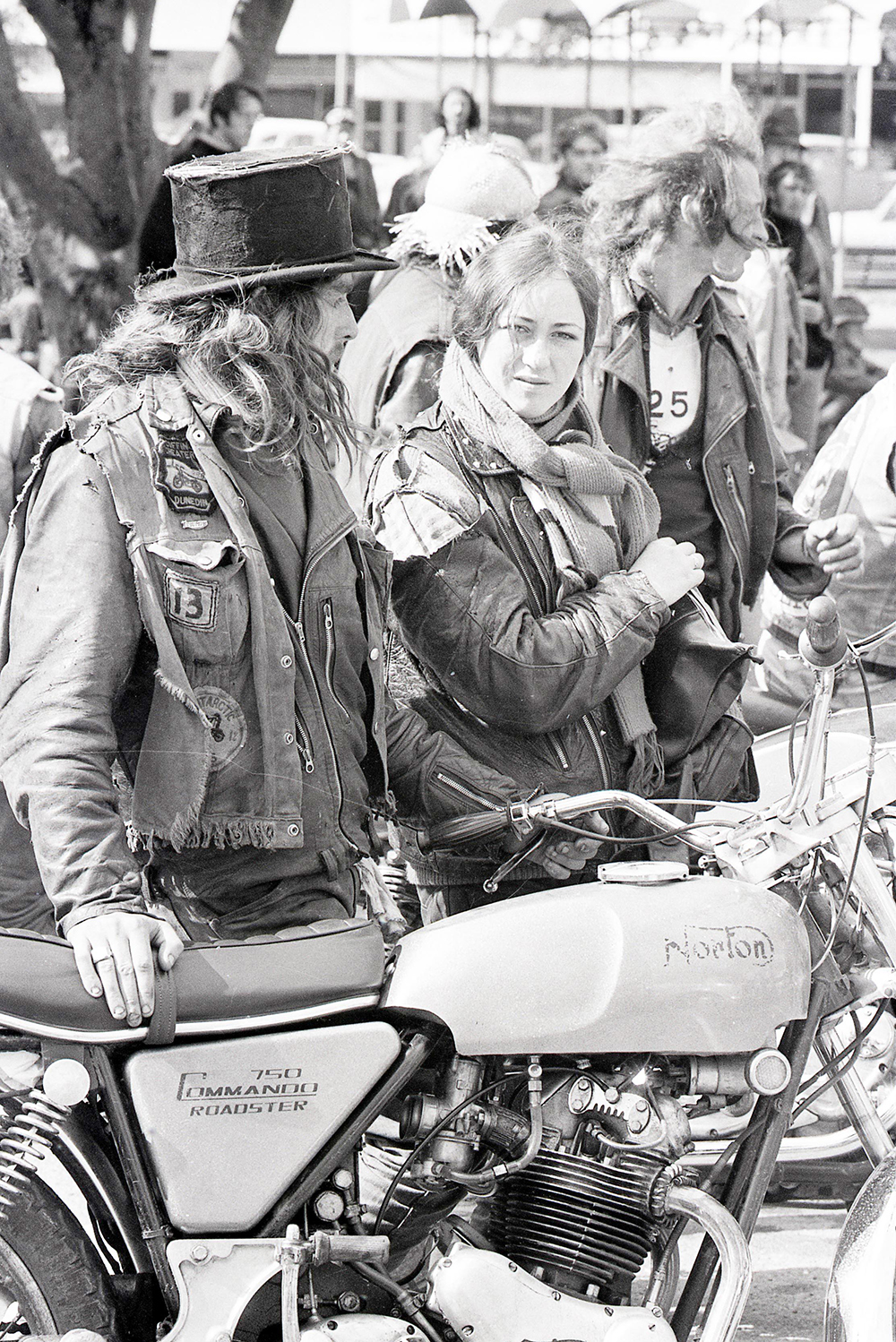

The slicked-back, Brylcreem Fonz (from Happy Days) hairstyle and black leather jacket was replaced by shoulder-length shaggy hair and the ‘Brando’ leather jacket covered by a battered denim ‘cut-off’ vest with a prominent patch sewn on the back.

The groups’ names such as Road Runners and 25 Club were being superseded by more confronting titles, such as Outcasts, Satan’s Slaves and Motherf***ers.

There was a boom in new clubs being formed. Even towns of 30,000 had a bikie group while Wellington and its outlying suburbs had at least three. Probably nowhere else in the world was there such an expansion.

WHO WERE THEY?

Most club members were young, many of them teenagers. Unlike the older milkbar cowboys, they didn’t care about having a full-time job. Their life was riding with the club. It was a time when it was easy to get a casual job to fund an alternative lifestyle. Big old houses were plentiful and cheap to rent, and the cost of living was low.

There were three sub-cultures developing in New Zealand, all based on a blueprint exported from the US: itinerant surfers, laidback hippies and bikies.

Life became one long party on the road, similar to an endless end-of-season footy trip. To quote the 1971 hit song from Australia’s Masters Apprentices: Do what you wanna do, be what you wanna be, yeeaaah!

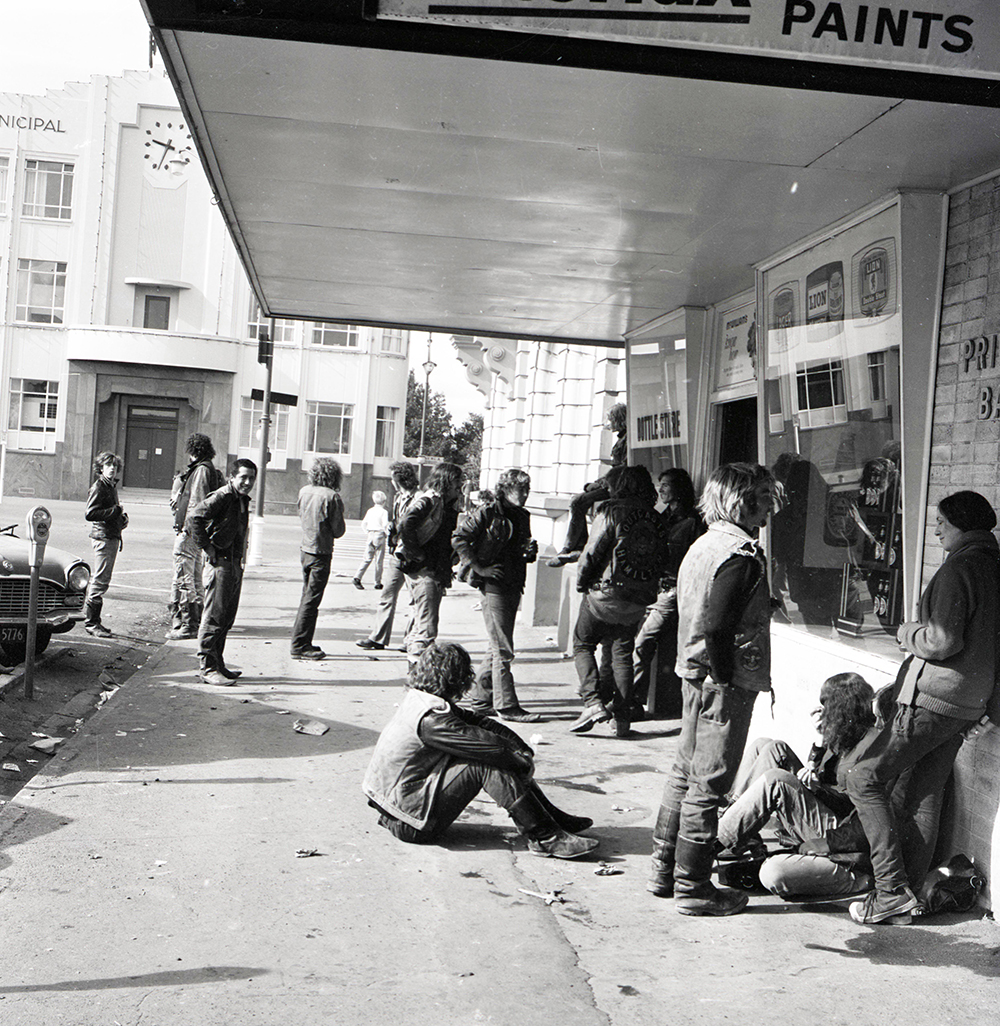

A group of 30 unkept-looking riders on noisy motorcycles with ape-hanger handlebars was an intimidating sight. When around 150 arrived in Palmerston North, a small inland rural city of 60,000, at Easter 1972, the stakes were raised.

It took organisation to get that many together from around New Zealand. What police called gangs were run like an incorporated club, with a hierarchy, weekly meetings, agendas and long-term plans.

THE INVASION

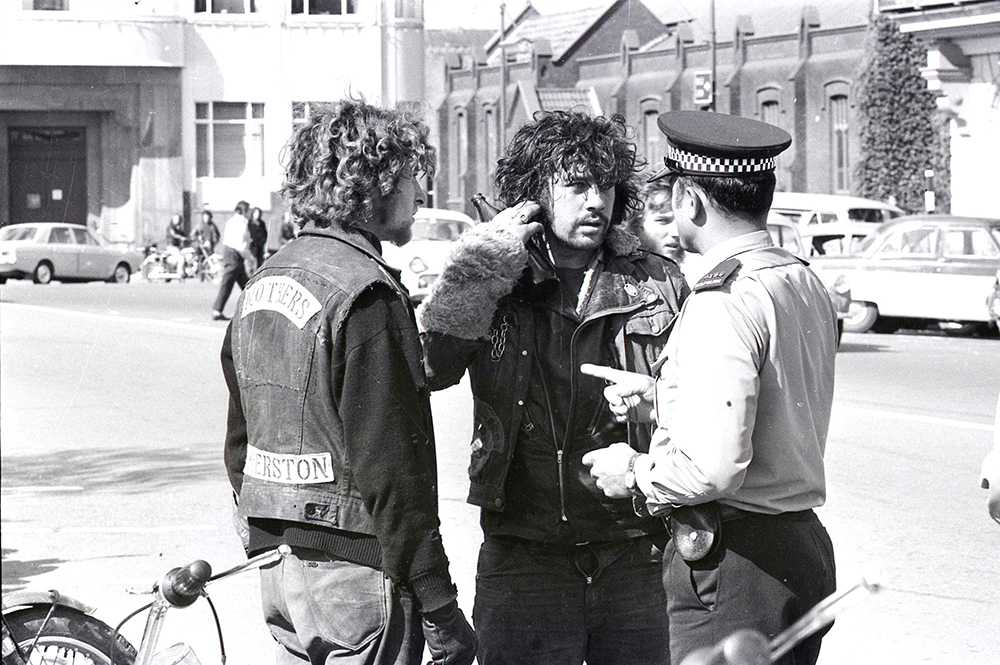

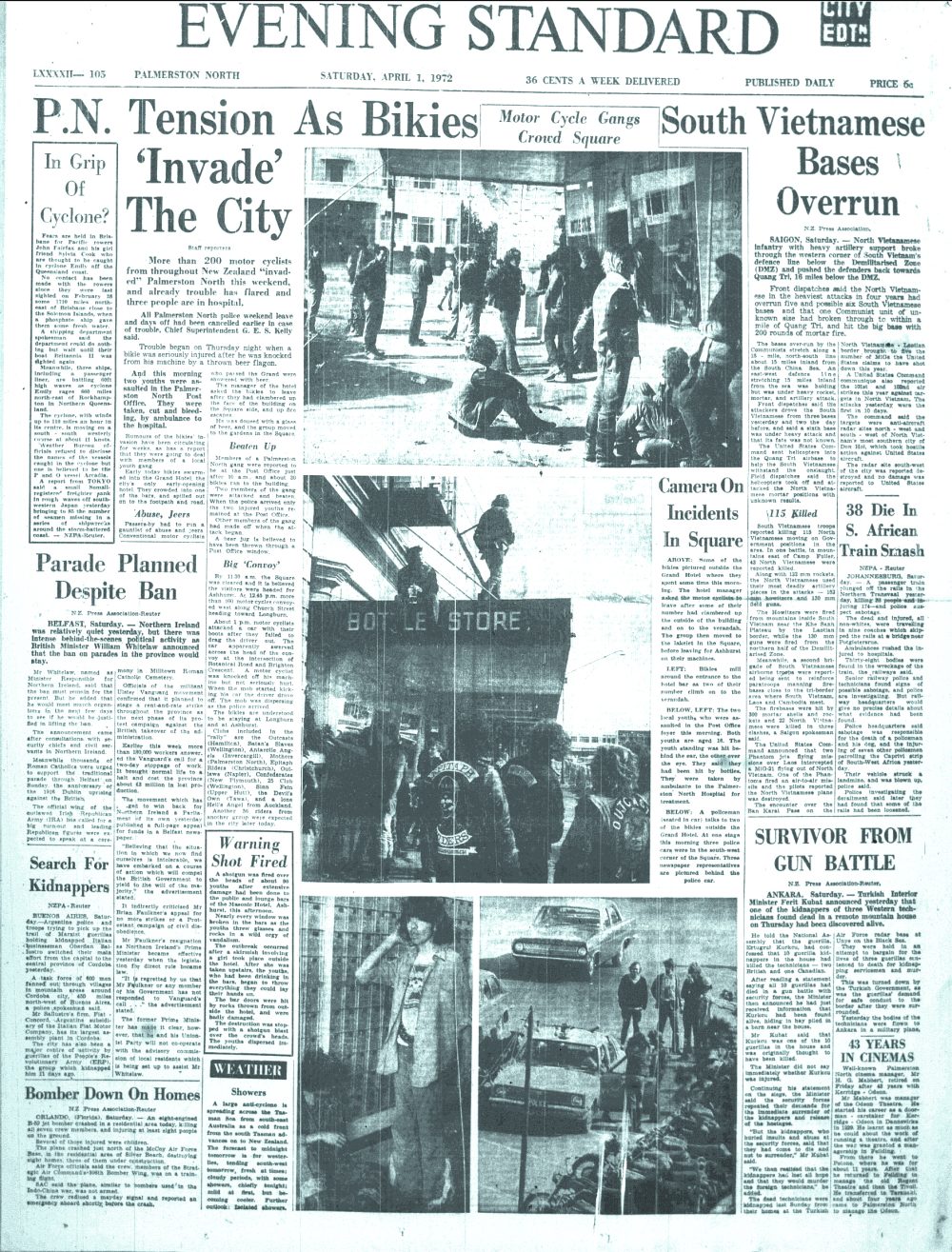

As the motorcyclists arrived, the Manawatu Evening Standard newspaper stated: “Rumours of the invasion have been circulating for weeks, as has a report that they were going to deal with members of a local youth gang.”

The newspaper coverage began to read like the script of that famous B-Grade Hollywood biker movie Hell’s Angels ’69 (The Rumble that Rocked Vegas).

“Trouble began on Thursday night,” the Saturday evening edition reported (newspapers didn’t publish on Good Friday), “when a bikie was seriously injured after he was knocked from his machine by a thrown beer flagon.”

Events started escalating early on Saturday morning.

“Bikies swarmed into the Grand Hotel, the city’s only early-opening hotel,” the report continued. “They crowded into one of the bars and spilled out onto the footpath and road.”

Reporters and photographers didn’t have to go far to get the story as their offices were opposite the Grand Hotel, a faded version of the once impressive building that had hosted royal tours. It would eventually close later that year.

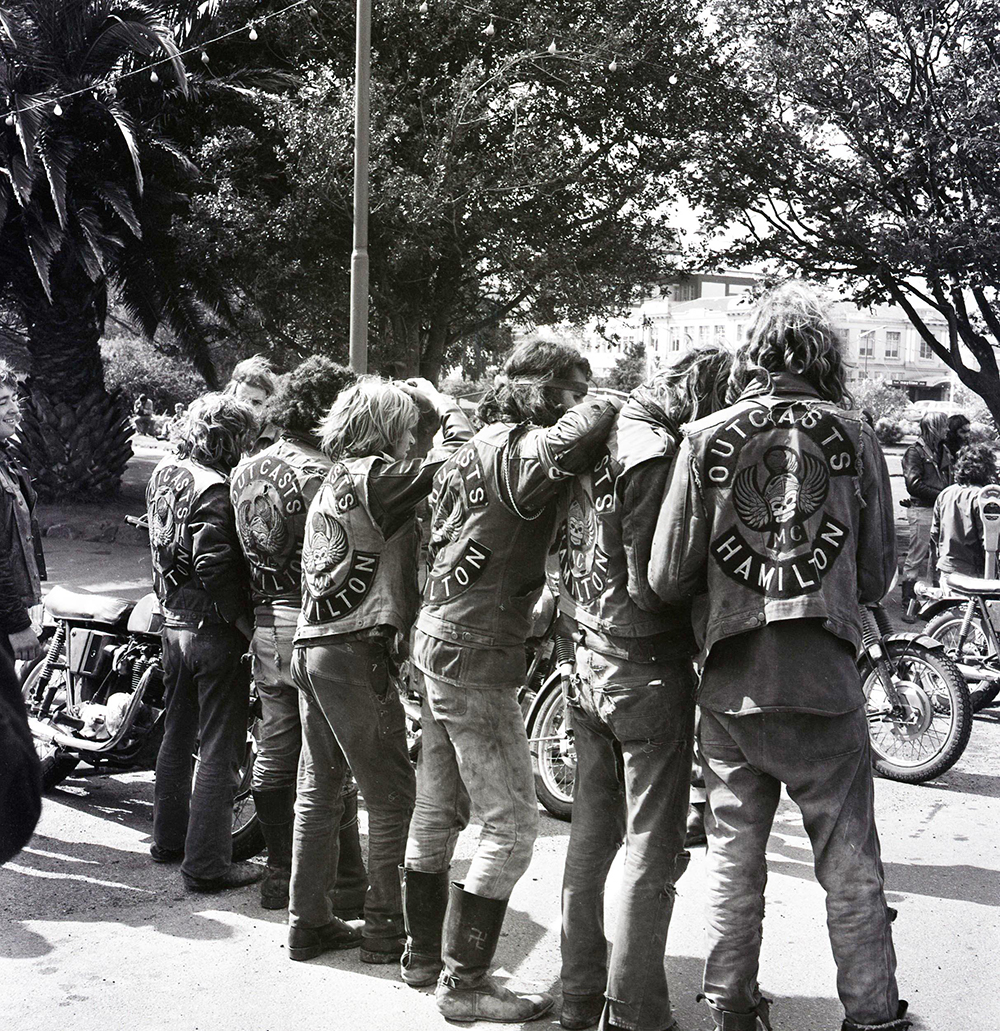

Directly across the road from the Grand Hotel was All Saints Anglican Church. Its neo-gothic appearance combined with the Grand Hotel’s French Napoleonic style to create an unlikely backdrop for the 120 or so bikies milling around. As the square, with its large lawns and ponds, was the retail centre of the city, Saturday shoppers arrived and several stayed to watch what must have seemed like a circus sideshow. Big British motorcycles were parked anywhere their owners cared, sometimes three deep and ignoring the parking meters.

Eventually, police persuaded the groups to move away from the Grand Hotel and they shifted to the other side of the square near a pond, where at least one stripped off and jumped in.

Then word came that members of the Mongrel Mob were near the Post Office.

The newspaper reported: “… 30 bikies ran to the building … when police arrived only two injured youths remained.”

Beside a photograph of the dazed youths, an extended caption read: “The two local youths who were assaulted in the Post Office foyer this morning. Both youths are aged 16. The youth standing was hit behind the ear, the other over the eye.”

Under the sub-heading Big ‘Convoy’, the Standard reported: “By 11.30am the Square was cleared … At 12.45pm more than 100 motorcyclists convoyed West… About 1pm motorcyclists attacked a car with their boots… The car had apparently swerved across the head of the convoy at an intersection… A motorcyclist was knocked off his machine.”

Saturday’s main report finished by naming clubs included in what it now described as a “rally”: “Outcasts (Hamilton), Satan’s Slaves (Wellington), Antarctic Angels (Invercargill), Mothers (Palmerston North), Epitaph Riders (Christchurch), Outlaws (Napier), Confederates (New Plymouth), 25 Club (Wellington), Sinn Fein (Upper Hutt), the Devil’s Own (Tawa) and a lone Hells Angel from Auckland”.

It said another 56 riders were expected later in the day. Meanwhile, police reinforcements were on their way from as far away as New Plymouth (three hours away) to boost numbers in Palmerston North to around 100. Mongrel Mob members from around the lower North Island were also heading to the city in cars.

Just below the main report was another with the heading Warning Shot Fired. It recounted how the publican at the nearby township of Ashhurst “fired a shotgun over the heads of about 90 youths after extensive damage had been done to the public and lounge bars” in the afternoon.

BLOOD FLOWS

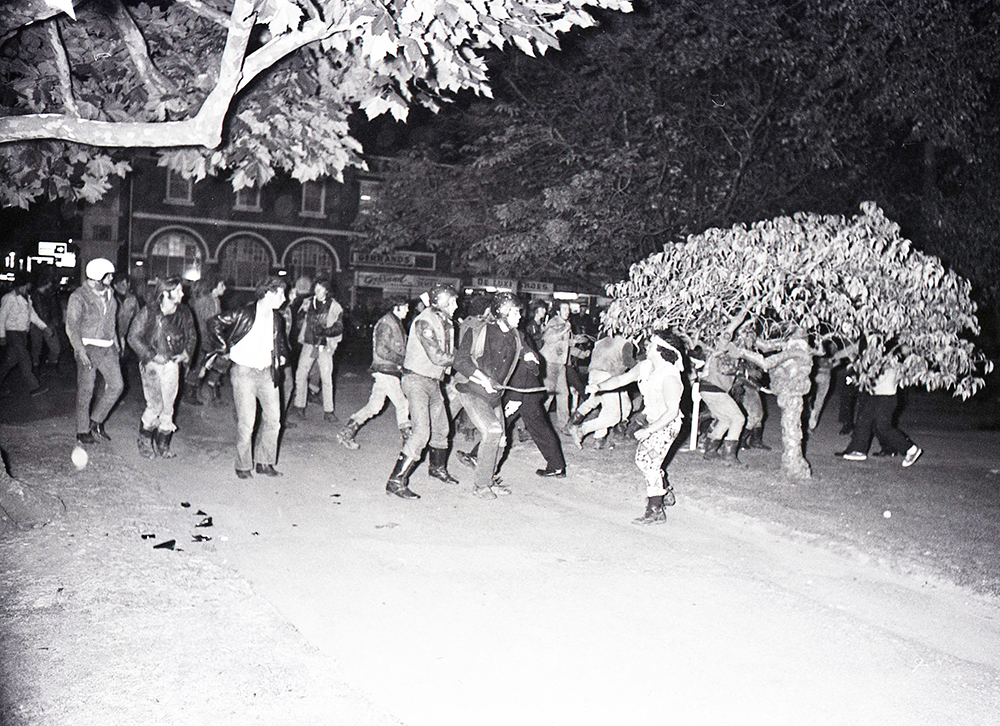

The newspaper didn’t print on Sunday but it was worth the wait for Monday’s front page. It was a ripper, with the heading Blood Flows in Square When Rival Gangs Clash, amazing photographs and a description of an all-in brawl with the Mongrel Mob at 9pm on the Saturday night.

“About 70 Mongrel Mob members, including many youngsters, were packed together in a corner of the Square when 80 bikies streamed in,” the paper reported. “Chains, marker posts, beer bottles, knives, a tractor lever and iron bars were drawn… fights broke out and no quarter was asked or given.”

The report was backed up by a number of confronting photos.

In his police history book, author Carter states: “We moved in just as the gangs started to clash… the fights had started in earnest and the bikies came well prepared.”

He noticed how some Mongrel Mob members were “disturbingly young”.

The newspaper says “the actual fighting lasted about 15 minutes and the Square was cleared after 30 minutes”.

Rather than being a full-on riot, it appears to have been a series of skirmishes with police running around using wooden truncheons to break them up. Interestingly none of the policemen were wearing any type of protective riot gear.

The newspaper described one fight: “A Mongrel Mob member, looking like a karate exponent, faced a group of bikies. Undecided for a second whether or not to rush him, the bikies held off until one of their number rushed through their ranks and fly-kicked the Mongrel.”

Twenty-two arrests were made and the newspaper described the relief as the bikers left the town the next day: “Tensions ebbed and peace returned.”

POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES

This event had major consequences, eventually becoming a political issue before the general election held later in 1972. Labour leader Norman Kirk promised to “take the bikes off the bikies”. New legislation prohibited unlawful assembly of more than three people wearing patches. As it was a street gang, the Mongrel Mob was most affected by this law.

In 1976 the laws were expanded to allow the confiscation of vehicles used to commit offences. As well, undercover detectives had started to infiltrate the clubs and thick dossiers were being compiled on members and their activities.

The noose was tightening, the stakes increasing. Nothing would be quite the same again for those involved. Ultimately, the main attraction in 1972 was the adrenalin hit of roaring down an open road in a group of 30 or more and making your own rules. Only those involved really knew what

it was all about.

Words Hamish Cooper Photography Stuff.co/nz/Maurice Costello/Manawatu Standard