The end of the 2021 MotoGP season brought the curtains down on the unforgettable career of Valentino Rossi and love was in the air at the last round in Valencia. Also clouds of yellow smoke, the sound of 75,000 shouting voices, and not a few sentimental tears. They had all come to share in a special moment in motorcycle racing… the end of an era that is unlikely ever to be equalled.

Only tenth place in his final race, for a rider who had chocked up 115 wins and nine world championships over an unprecedented 26-year winning career was neither here nor there. Aged 42 and still racing at the highest level, this was simply the celebration of a genuine legend.

Valentino Rossi was always a brilliant racer – one of the best ever, natural talent combined with an iron will. But so much more than that: Rossi is a gigantic character – unpredictable, witty, self-assured, mischievous. A one-off, with a rascally sense of fun, who shares his joie-de-vivre and his devilment, and did more than just illuminate sport with it.

Rossi celebrated with a doctor as pillion in 2001 and has stuck with the moniker ever since

Rossi celebrated with a doctor as pillion in 2001 and has stuck with the moniker ever since

Rossi’s charisma took motorcycle grand prix racing by the scruff and held it to world scrutiny, bringing himself and his sport to the attention of hundreds of thousands of people worldwide who, without him, would probably not even

have noticed it.

Clever and astute, and commanding the brains and loyalty of his close circle – the original Tribu dei Chihuaha – in his home village of Tavullia, he also monetised it. With apparently natural inspiration, he built the yellow VR46 logo and ‘The Doctor’ nickname into a brand. It is now a comprehensive bike-racing business, and he became one of the top-earning sportsmen of his era.

Emotional scenes after his last-ever race as a MotoGP rider

Emotional scenes after his last-ever race as a MotoGP rider

Much more than that. Rossi and his cohorts created an all-new pathway to stardom for those who wanted to follow him. While there are highly successful Spanish rider development programmes, the VR46 Academy is unique, and the world’s best racer-training foundation. It has developed and continues to develop a legacy of Italian racing talent that perpetuates his legend.

The winner of his final GP in Valencia, Pecco Bagnaia, is just one of his proteges. There’s also Franco Morbidelli and his half-brother Luca Marini in the premier class, plus a bunch in Moto2 and Moto3, including race winners and podium finishers Marco Bezzecchi, Celestino Vietti, Andrea Migno, Niccolo Bulega and several others.

The last round was approached in the same way as the 431 that came before it

The last round was approached in the same way as the 431 that came before it

Along with the VR46 team which has grown up through Motos 3 and 2 to a fully-fledged MotoGP squad next year, this reflects his long-standing the sun-moon helmet logo, which speaks of the light and dark sides of his character. Take, and once you’ve done so, also give.

His retirement (as one of his several deadly rivals Jorge Lorenzo put it on the day it was announced) is epochal. Writing on Twitter, Jorge (who twice beat him to the title) said: “End of an era. On the track the four of us were just as fast, but in terms of charisma or transcendence @valeyellow46 is at the level of Jordan, Woods, Ali or Senna.”

Rossi said he had concerns about the four-story-high mural painted in his honour at Valencia. But he’s happy with the result

Rossi said he had concerns about the four-story-high mural painted in his honour at Valencia. But he’s happy with the result

This torrent of tributes was followed by fans and rivals from all branches of motorsport and beyond at the time, and repeated at Valencia, where Brazilian football legend Ronaldo was just one present to share in the moment, along with his great rivals over the years Casey Stoner, Jorge Lorenzo, Dani Pedrosa, Loris Capirossi…

Valentino’s path to glory might have been written in the stars. It had been gilded, thanks to prescient support from Aprilia and the Italian racing establishment, and also his grand-prix-winner father Graziano. And it had been rapid. He showed it as a 10-year-old in a kart, which Graziano preferred to motorcycle racing as being safer. But Valentino knew that four wheels were two too many.

Most importantly, he had the killer instinct. In spades. A ruthless streak that the cheerful charm couldn’t quite conceal.

I recall asking him once if he ever felt even an ounce of empathy with any beaten rival. He threw back his head and gave his trade-mark cackling laugh. It had clearly never occurred to him. Rather the reverse. He preferred to crush his rivals on and off the track.

As he said, at his retirement press conference, “A real racer doesn’t go racing for fun. You are there for the results. To win.”

This was his driving force from his first outings on a go-kart, then as a pre-teen switching to minimotos, until beyond his last win in 2017 at Assen.

If it is possible to pick a defining moment out of the longest world championship grand prix career (on two or four wheels), it happened not even one third of the way through.

The Doctor spoke to his YZR-M1 ahead of a race for the very last time on 14/11/21 which, incidentally, adds up to 46

The Doctor spoke to his YZR-M1 ahead of a race for the very last time on 14/11/21 which, incidentally, adds up to 46

It was a sunny afternoon outside the dusty gold-mining town of Welkom in South Africa, and Valentino – aged 24 – was already five times a champion, once each in 125 and 250, thrice in the premier class.

Already wildly popular – his speed, skill and showmanship unsurpassed, his charm and trademark put-downs to his rivals and his post-race pantomime celebrations had made him so. But now he had taken the greatest gamble of a high-risk life. Feeling undervalued at Honda, whose engineering-bent management valued machinery more than manpower, he had jumped ship, and switched to underdog Yamaha.

Valentino qualified ahead of his dear friend and first VR46 Academy recruit Franco Morbidelli, and led him over the line to finish 10th

Valentino qualified ahead of his dear friend and first VR46 Academy recruit Franco Morbidelli, and led him over the line to finish 10th

The move, accomplished after undercover negotiations, had been “do or die mission” for Yamaha, long-standing head of the racing department Lin Jarvis explains. “We hadn’t won a championship for 12 years [actually 11]; we were getting beaten up by Honda. But if you take the best rider in the world, and you don’t succeed…”

Throughout the negotiations, Rossi had spoken about how he wanted to have fun again in racing. Yamaha responded with a hastily reconfigured M1, raised on its suspension after his early tests, powered by a crucially redesigned inline-four engine, with revised firing intervals that emulated the more tyre-friendly power stream of a V4.

This bike brought a new exhaust note to the tracks for the opening round of 2004. And new rider Rossi put it on pole position. But the race was far from easy. He had to fight every inch of the way with bitter rival Max Biaggi, culminating in a bare-knuckle last lap. Rossi won it by less than half a second.

On the slow-down lap he stopped, leaned the bike against the barrier, and slumped onto the ground, bent forward, shoulders tumbling. It looked as though he was weeping. He took most of the rest of the year to correct that impression.

“I was laughing,” he eventually disclosed.

Valencia MotoGP race, 14 November 2021

Valencia MotoGP race, 14 November 2021

As well he might. The achievement was far greater than one race win, and one more humiliation of Biaggi. For Yamaha, said Jarvis, “He gave us the faith back to all in Yamaha racing.”

A faith that the factory generously repaid.

It was 18 years ago in Valencia that Rossi had his last-ever ride on a factory Honda

It was 18 years ago in Valencia that Rossi had his last-ever ride on a factory Honda

Rossi came to MotoGP in 1996, riding a factory-backed 125 Aprilia. He took his first win at Brno that year – narrowly beating multi-champion ‘Aspar’ Martinez, now a rival team owner – then the championship in 1997. His big personality was noticeable from the first, a laughing cavalier of sheer enjoyment.

On to 250 in 1998 for two years with Aprilia, and more of the same: race wins in his first year, the championship in the second. By now he was an accomplished entertainer, but he’d learned to be more careful with the press. His fellow-Italian journalists might seem friendly, but they would not hesitate to bite.

Fittingly, the number 46 has completed a total of just over 46,000 race kilometres

Fittingly, the number 46 has completed a total of just over 46,000 race kilometres

It was one aspect of a growing worldliness that he kept well hidden behind his growing penchant for post-race play-acting, and beneath an ever-changing variety of hairstyles and colours… including a memorable half-white/ half-black version.

In 2000, the big-time welcomed the burgeoning new star. Riding in an independent Honda team, inheriting not only the mighty NSR Honda that had taken Mick Doohan to five successive titles but also the highly successful Jerry Burgess-led pit crew left at a loose-end by Mick’s career-ending crash in 1999, Rossi had arrived at where he was meant to be.

Randy Mamola ‘celebrates’ Rossi’s 2001 title at Phillip Island

Randy Mamola ‘celebrates’ Rossi’s 2001 title at Phillip Island

Again, one year to learn – the first of two 1999 race wins coming in Britain, and one year to win. But that was just the start of it. Those were the first of 89 race wins, 2001 the first of seven championships – four more over the coming years, a further two in 2008 and 2009. The first three were with Honda, the next four with Yamaha.

To list his achievements would take pages. A small selection draws a clear picture.

The post-race celebration in the garage after his fine 10th place

The post-race celebration in the garage after his fine 10th place

There was his domination at two of the fastest classic tracks, where a rider can really give a MotoGP bike its head. At Mugello Rossi won every year from 2002 to 2008; at Australia’s Phillip Island he owned the circuit from 2001 to 2005.

His first-ever grand prix win in Brno in 1996. There have been another 114 since

His first-ever grand prix win in Brno in 1996. There have been another 114 since

One could go on, but for this writer, present at every one of his 115 race wins in all three classes, as well as the 2004 South African GP, two more achievements stand out.

The first followed on from Welkom, when he won the 2004 championship for Yamaha, to add to three won on a Honda. To that point, only four riders in history had won the premier title on different makes of motorcycle, all legends: Geoff Duke, Phil Read, Giacomo Agostini and Eddie Lawson. Only Lawson did so on consecutive years. And now also Rossi.

The 1998 victory in front of his growing number of home fans at Imola was his second 250cc win

The 1998 victory in front of his growing number of home fans at Imola was his second 250cc win

The other was the Australian GP of 2003. Valentino was already champion, so he could afford to relax, but he planned to win. It was the wake of Barry Sheene’s death, and Rossi acknowledged Barry as his true predecessor – a gifted entertainer who had taken bike racing beyond its niche boundaries. He planned a celebration if he was to win, taking one of the bed-sheets from his hotel and painting Sheene’s number 7 on it. “Sorry, hotel,” he said afterwards.

He took control of the race, a little clear of a big brawl behind him, comprising Hayden, Melandri, Capirossi, Gibernau and briefly also Troy Bayliss and Max Biaggi, before the former knocked the latter off. But one of his passes to get there had inadvertently been under a yellow flag. Ten-second penalty.

Rossi, Valencia MotoGP 2003

Rossi, Valencia MotoGP 2003

This forced him to show the full measure of his ability. Where usually he was content at least to make races look close, in the interests of entertainment, now he needed to make a margin. It was, he said later, the first race that he had ridden at 100 percent for the full distance. He won by a country mile, adding almost another five seconds to the 10 he needed to make sure Capirossi was only second, and he could display his painted bed sheet.

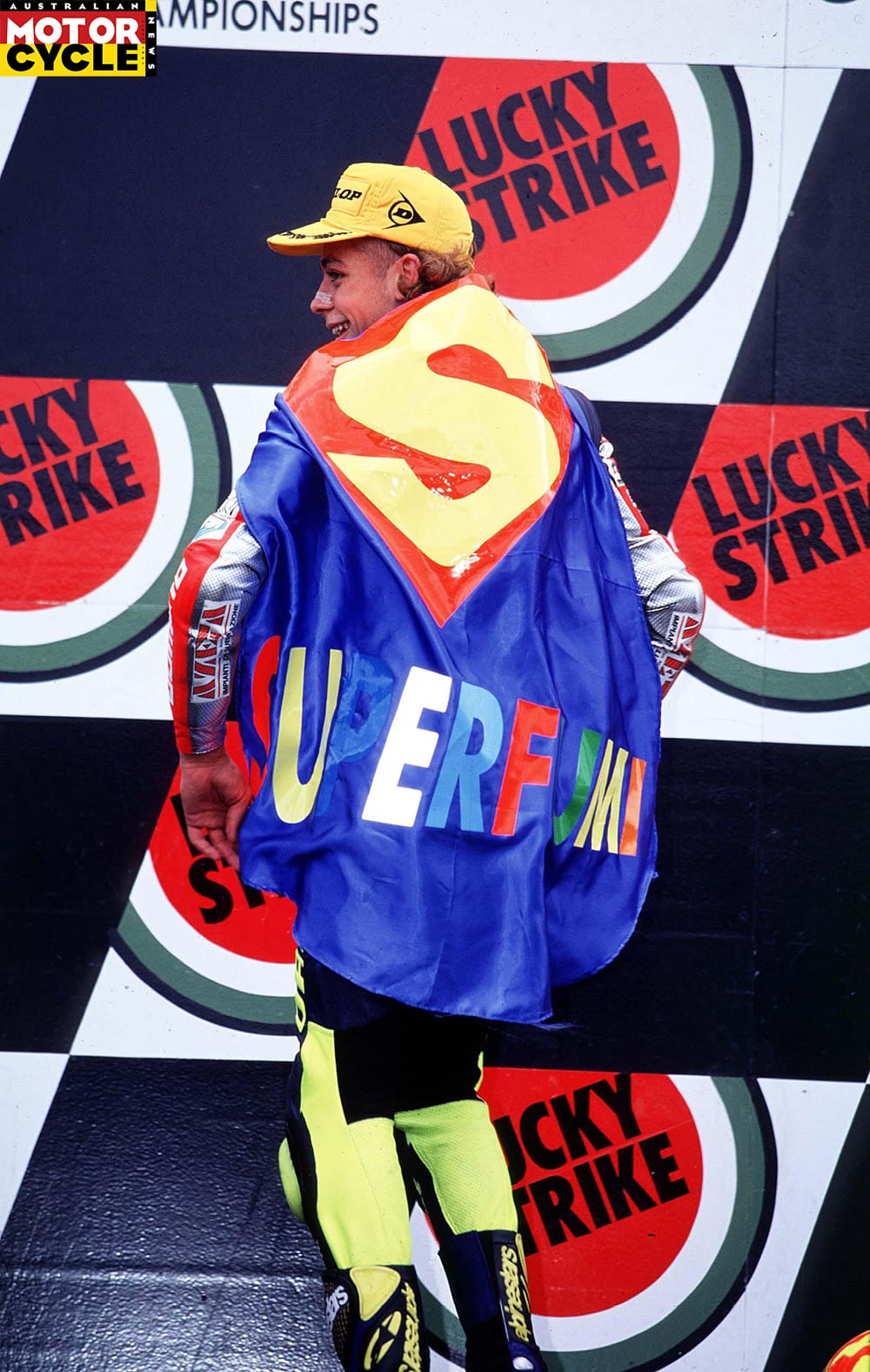

On and off the track, Rossi was always an entertainer; the value of pleasing the crowd was something he not only understood better than any successful rider before him, and probably since; but was also able to accomplish. He had a real gift. He was already working up the cult of personality from his earliest GP years, on a 125

in 1996 and 1997.

Prankster Randy Mamola on the grid with Rossi ahead of the 2000 season-ending Aussie GP

Prankster Randy Mamola on the grid with Rossi ahead of the 2000 season-ending Aussie GP

In his first years in 125, with reference to his many Japanese rivals and an early demonstration of his awareness of the importance of branding, he adopted the nickname ‘Rossifumi’. (This later gave way to ‘Valentinik’ in honour of a Disney character, before he adopted his permanent nickname ‘The Doctor’ in 2001.

Entertainment is something he celebrated at the announcement of his retirement.

Rossi’s crew made him a cape to celebrate the 1997 victory at the Dutch TT

Rossi’s crew made him a cape to celebrate the 1997 victory at the Dutch TT

“The difference between me and other great riders… I was able to bring a lot of people close to motorcycle racing. I did things to switch on the emotion, and I entertain a lot of people on Sunday. I am very proud. I think for this I am a legend.”

Some of that entertainment was just from the way he raced. He was never less than committed and spectacular. Classic overtaking moves were a hallmark.

Rossi reenacted his first and most famous victory with the Yamaha during his last outing before switching to Ducati

Rossi reenacted his first and most famous victory with the Yamaha during his last outing before switching to Ducati

There was the move on Max Biaggi at Suzuka, after his rival had ridden him onto the grass on the main straight, Vale went round the outside at the first corner, and flipped him the bird as he went by. The one on Casey Stoner at Laguna Seca, taking the second apex at the Corkscrew a metre

or two inside the white line, on the dirt.

A bitter Stoner commented: “I lost some respect for Valentino today.”

Sideways on his way to victory during the 2004 Catalunya Grand Prix

Sideways on his way to victory during the 2004 Catalunya Grand Prix

The surprise move on Jorge Lorenzo at Catalunya in 2010, after he seemed beaten on a breathtaking last lap, with an unprecedented inside swerve into the last corner… and who will ever forget when he barged bitter rival Sete Gibernau wide at the last hairpin at Jerez?

Then there were the pantomimes. Whether it be putting a man in a chicken suit on the pillion, rushing to the toilet, getting a mock speeding ticket or miming working on a chain gang. Other riders have imitated, none have come close – though Lorenzo had to be rescued from drowning after jumping into a lake at Jerez in 2010.

That he, or his fans, weren’t aware the 2019 Australian Grand Prix was to be his last is a disappointing outcome for a rider who has so many great memories at Phillip Island

That he, or his fans, weren’t aware the 2019 Australian Grand Prix was to be his last is a disappointing outcome for a rider who has so many great memories at Phillip Island

All of it built his brand, and promoted racing, as his fame spread far beyond the fans who would have been dedicated with or without him. Cal Crutchlow summed it up, saying: “No matter where you are in the world, when you say motorbikes, people just say Valentino Rossi.”

Rossi made a huge one-man contribution to the growth of MotoGP. Among the riders, he took the lion’s share of the benefit – as Barry Sheene had before him. But he pulled the rest along behind him; everybody’s earning power increased. More importantly, he helped Dorna to pull racing through the perilous financial times after the loss of tobacco sponsorship and in the 2008 financial crisis, making it possible for the series to expand internationally as never before. Be it in Rio de Janeiro or Australia, China or the USA, the instantly recognisable figure on the publicity posters always wore the number 46.

Rossi, Austrian GP 1996

Rossi, Austrian GP 1996

It wasn’t all plain sailing, which underlines his persistence and makes the unprecedented length of his career all the more remarkable. Most ghastly, the accident that killed Marco Simoncelli in Malaysia in 2011. Marco was a friend and protégé, but fell right under the wheels of Rossi’s Ducati and Colin Edwards’s Yamaha.

There were the well-publicised tax problems in 2007/8, settled in negotiation with the Italian authorities, for a payment variously reported as between 18-million and 51-million Euros.

There was the blight on his charmed injury-free life, with a double leg fracture at Mugello in 2010. He was back in action just 41 days later, setting a record for the forced pace of his recovery and missing only four races. He suffered a lesser leg fracture in a training crash in 2017, but has otherwise had a remarkable ability to bounce back from crashes.

Rossi right Burgess left Sepang MotoGP Ducati test 2011 2012

Rossi right Burgess left Sepang MotoGP Ducati test 2011 2012

Then there was, in 2008/9 the perceived betrayal by Yamaha, when they signed Jorge Lorenzo as his teammate. Famously there was a wall down the middle of the factory pit box: nominally because they were on different tyre brands but also because Rossi refused to share data. He went public, saying if they kept Lorenzo he would leave… and that is what happened.

His move to Ducati for 2011 and 2012 was contrived as revenge and as a chance to prove to 2007 Ducati champion Casey Stoner that the right rider could fix the subsequent lack of success for the Desmosedici. That went badly wrong. While Stoner smashed the title on his new Honda, Valentino struggled to make the podium on the recalcitrant beast.

Misano 1993 Cagiva 125 sport production Luca Villa Cadalora Valentino Rossi

Misano 1993 Cagiva 125 sport production Luca Villa Cadalora Valentino Rossi

At his retirement conference, however, he declined to express any regret. “The Ducati was very difficult, but it was a great challenge – an Italian rider on an Italian bike.”

He was, he admitted, “a little bit sad not to win 10 championships. I lose two times in the last race, so I think I deserve 10.”

What next? Car racing, and team management. And fatherhood, with a daughter on the way.

Valentino Rossi, Emilia-Romagna MotoGP, 23 October 2021

Valentino Rossi, Emilia-Romagna MotoGP, 23 October 2021

“I will miss the life of an athlete, to get up every morning to train. I will miss the team, and the emotion of Sunday morning, the two hours after you wake up, and feel nervous for the coming race.

“But especially I will miss to ride a MotoGP bike – it really is a great feeling.”

MotoGP Racing will miss him more. We move on to a new era. It won’t necessarily be worse, and in many ways it will be better.

But it definitely won’t be the same.

Interview Michael Scott Photography Gold&Goose