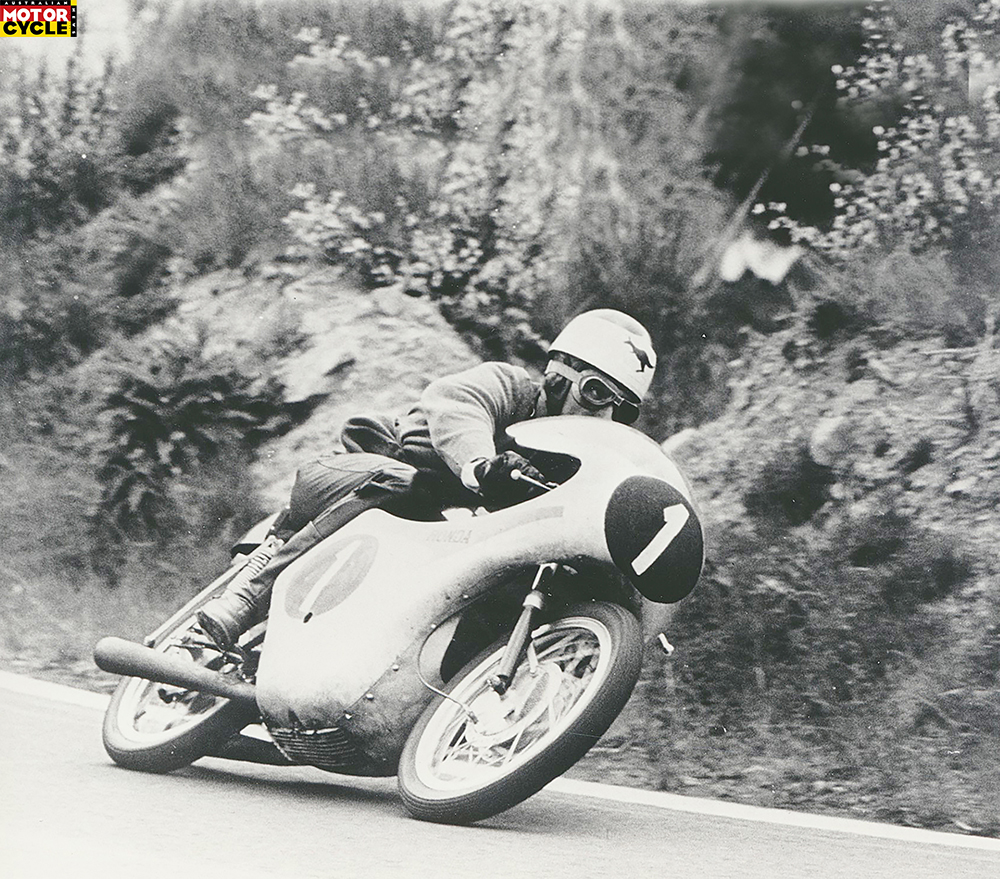

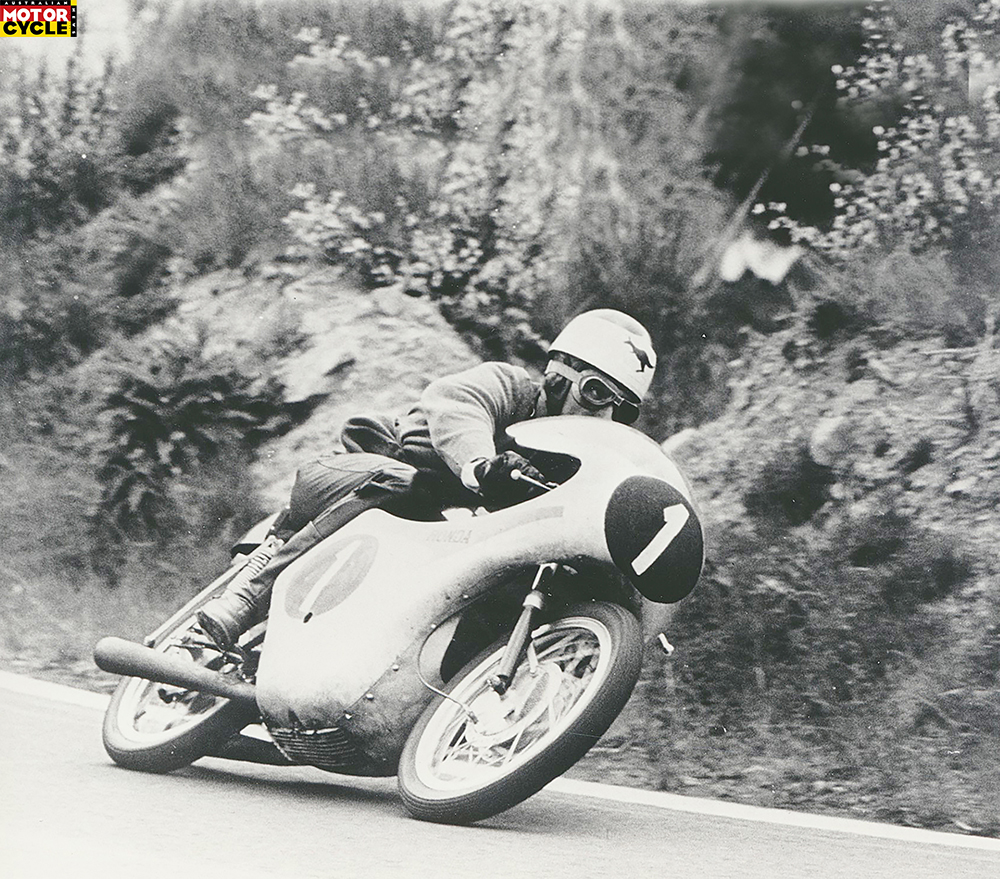

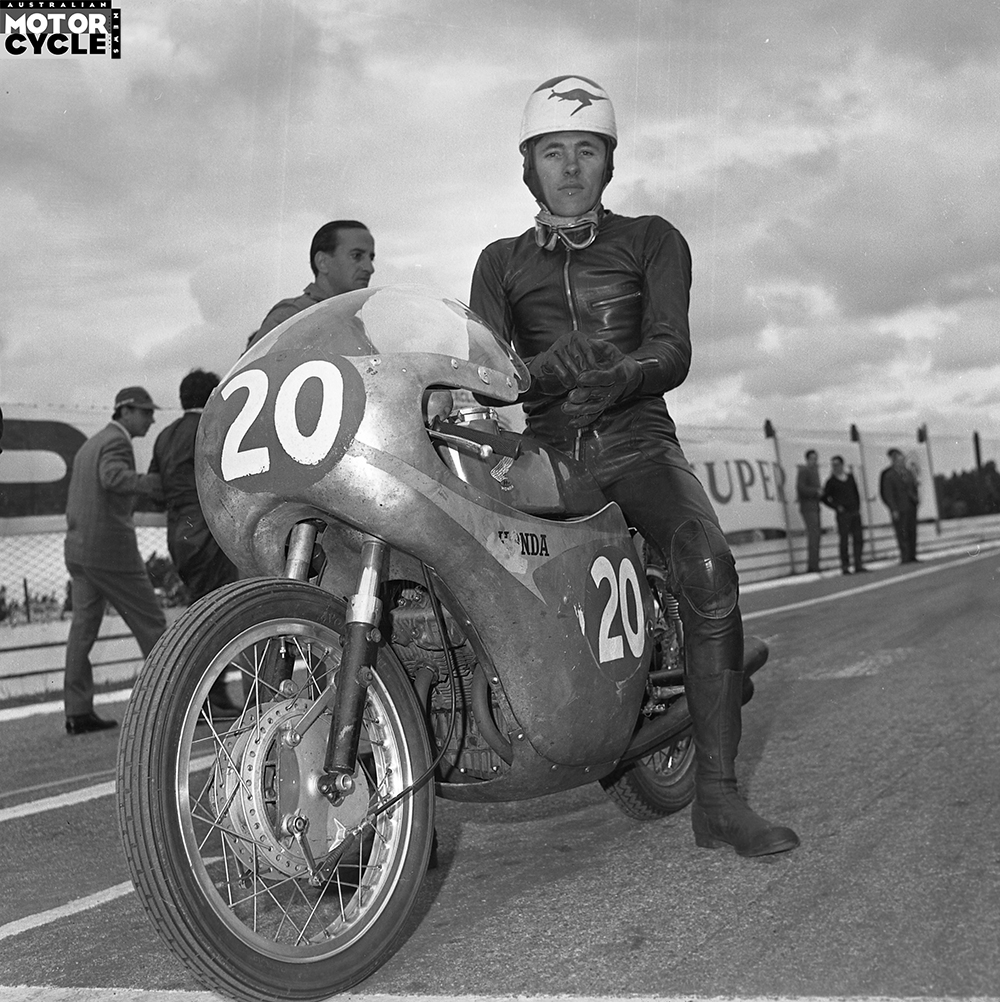

Hisakazu Sekiguichi was on a mission. As Honda team manager, he had to ensure Tom Phillis won the final round of the 1961 125cc title in order to secure the crown. Phillis’ eight-valve twin had to complete 50 laps of the 2.652km Autodromo Municipal De La Cuidad De Buenos Aires.

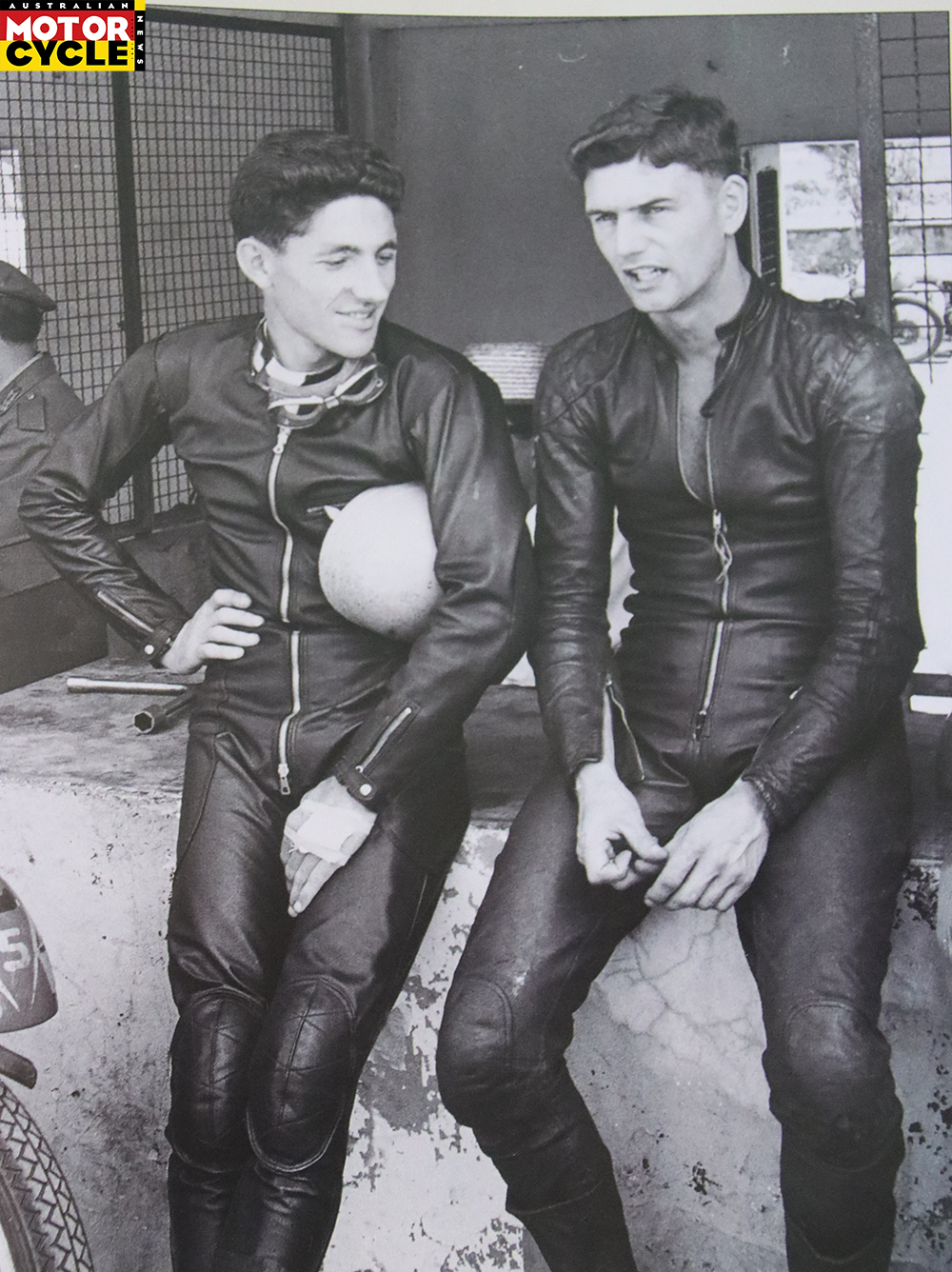

Phillis, 27 at the time, had his fingers crossed. After four seasons as an international racer, the last two with Honda, he was on the cusp of becoming Australia’s second world motorcycle Grand Prix champion. The 125 championship was the only 1961 title still to be decided and Honda sent a full team to Argentina – regular works riders Phillis, Jim Redman and Kummitsu Takahashi on 125s and 250s, with an extra machine for the top local.

It was the first world championship GP held outside Europe. Race conditions were marginal; it was raining. Phillis was in form; he’d won the previous day’s 250 GP by nearly half a minute, but over 35 laps of a different (3.912km) circuit layout.

The morning after the race, Phillis sent a telegram to his parents Tom and Elsie in Sydney.

“Home in three weeks with title – Ted.”

‘Ted’ was the name Thomas Edward Phillis was known by in his family, to avoid being confused with his old man.

On the Tuesday, Phillis wrote home from the Hotel Continental in Buenos Aires. Half a world away, wife Betty and their two young children were sailing to Sydney for the summer on Britain’s newest ocean liner, SS Oriana.

Phillis covered family matters and the future, before discussing the races. In this and following excerpts, we see a different world: the pressures, potential machine dramas and the injuries that might have ended his dream.

“The immediate past has been all rain here in Buenos Aires, especially the 125 race on Sunday, which was an easy ride for Jim and I with instructions from the pits to take it easy all the time. Jim finished a length behind with Takahashi third after crashing with a few of fastest local riders early in the race. The team manager was overjoyed, especially as they had spent the week making sure my 125 would go the full 50 laps. Changed the engine once – found a crack in frame on the eve of the race – fitted a mudguard just before the race and (that) seized the front forks with one of the mounting bolts…

“I get on well with the team. The manager Sekiguchi was the manager of the original 1960 team. His job was to make sure I won the 125 race, so everyone’s happy, except poor Ernst Degner, who had to watch on the sidelines due to a shambles in the transport arrangements of his EMC from London. (More on Degner later.)

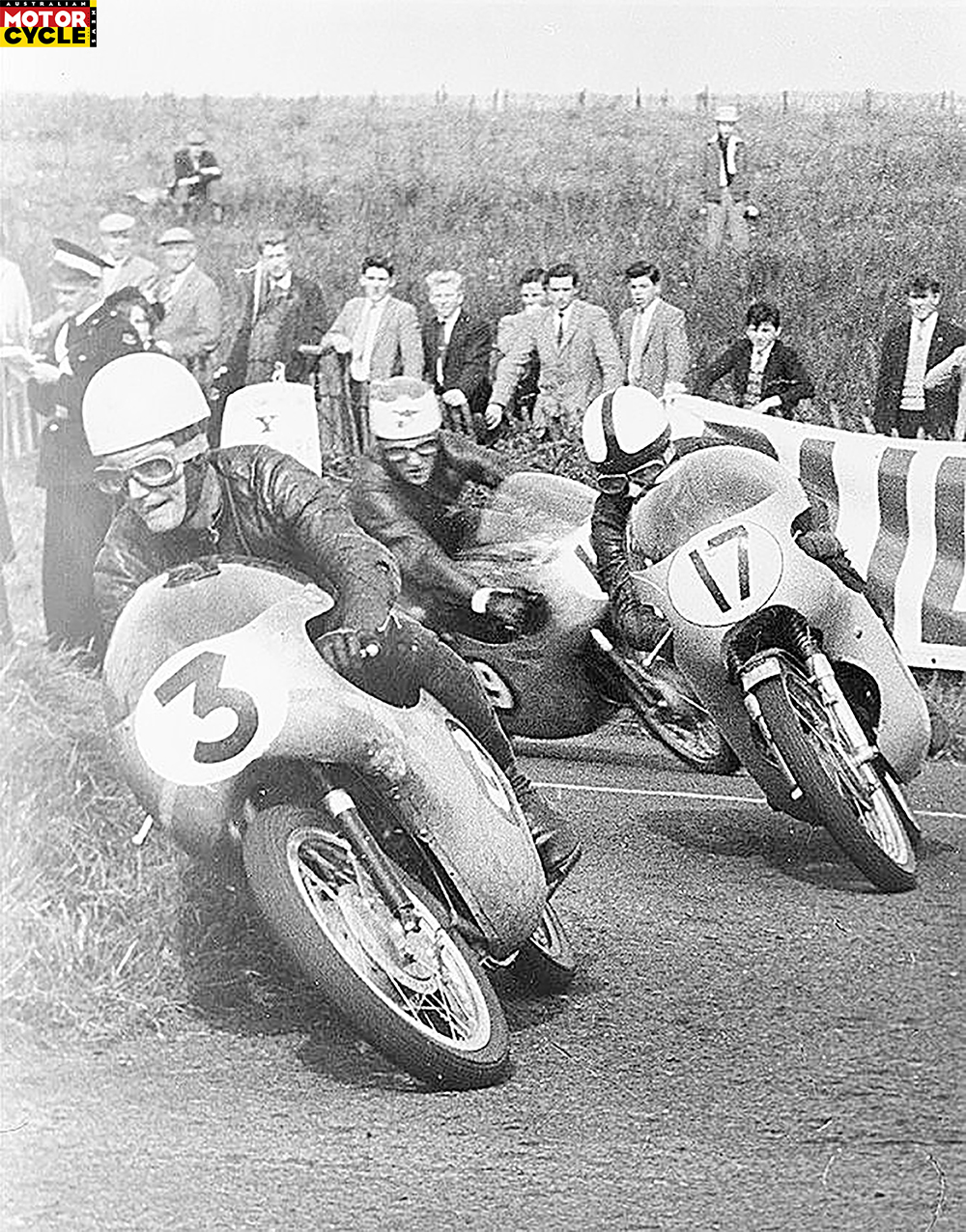

“The 250 race was run in drier weather on a larger circuit – 35 laps to do and it was a Honda benefit, with only one Yamaha (Fumio Ito) and a Suzuki apart from four Hondas in the race. At the start, the local champ (Benedicto) Caldarella took his Honda into the lead and held it there for two laps, followed by Takahashi, with Jim’s bike fizzing at the starting line. After two laps, I shot through and left Calda and Tak to fight for second spot, with Tak getting the better of him. Then Calda pulled into the pits, said it wasn’t handling properly and retired. However, Jim kept in favour by keeping going with a sick engine and eventually running third. Then with the ‘take it easy’ signal hanging out from the pits, we circulated in that order to end the ’61 championship. I think my 250 win brings me to second place (to Mike Hailwood) in that title.

“That’s all for now. I’m looking forward to seeing you all soon and to see the new maestro (a nod to his father) ride his Velocette. ‘Hasta la vista’, Ted.”

Phillis’s Argentine double gave him six victories for the season, four in 125s and two in 250s, and his second double victory. No Australian rider would better those marks until Gregg Hansford in 1978. Only two Australians have recorded GP doubles.

The championship was the pay-off for an act of faith two years earlier when, as a second-year Continental Circus private entrant, Phillis had written to company founder Soichiro Honda, asking for a ride.

He’d seen the potential when Honda Motor Company entered the 1959 Isle of Man 125 TT, run on the 11km Clypse circuit, finishing sixth, seventh and eighth.

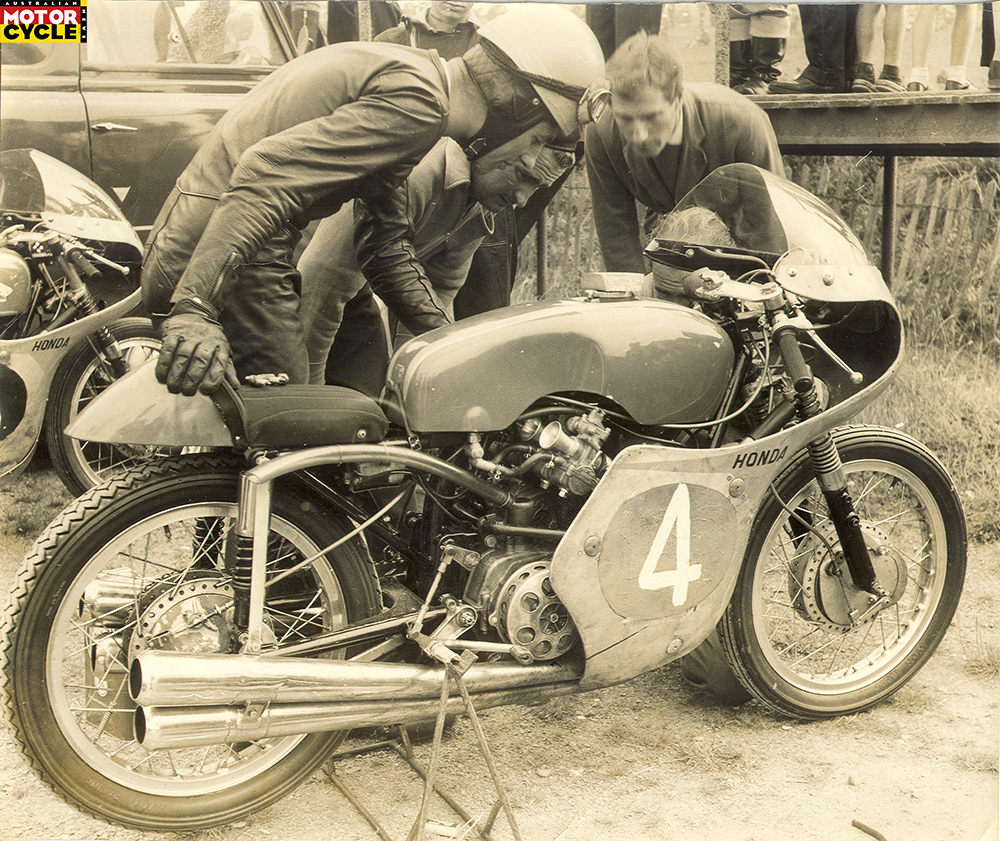

Honda returned in 1960 to face an added challenge. All races would be held on the Mountain Circuit. It brought both new-look 125s and, stunningly, 16-valve four-cylinder 250s. Phillis was now a works rider, supported by compatriot Bob Brown for the TT.

Phillis capped his 1960 season by finishing second in the Ulster 250 GP, a bare two seconds behind the winner. This was the closest a Honda rider had come to winning a world championship event.

Honda launched full 125 and 250 programs in 1961. Phillis and Redman visited Japan to test the bikes in March 1961. Flying to London, Phillis wrote: “The 1961 racers have some surprising changes and should be the goods… here’s hoping for a bit of luck to back up the hard work.”

Honda used the 1960-model works racers for the early season international events and the opening GP in Spain, with the new machines fresh for the West German GP at Hockenheim.

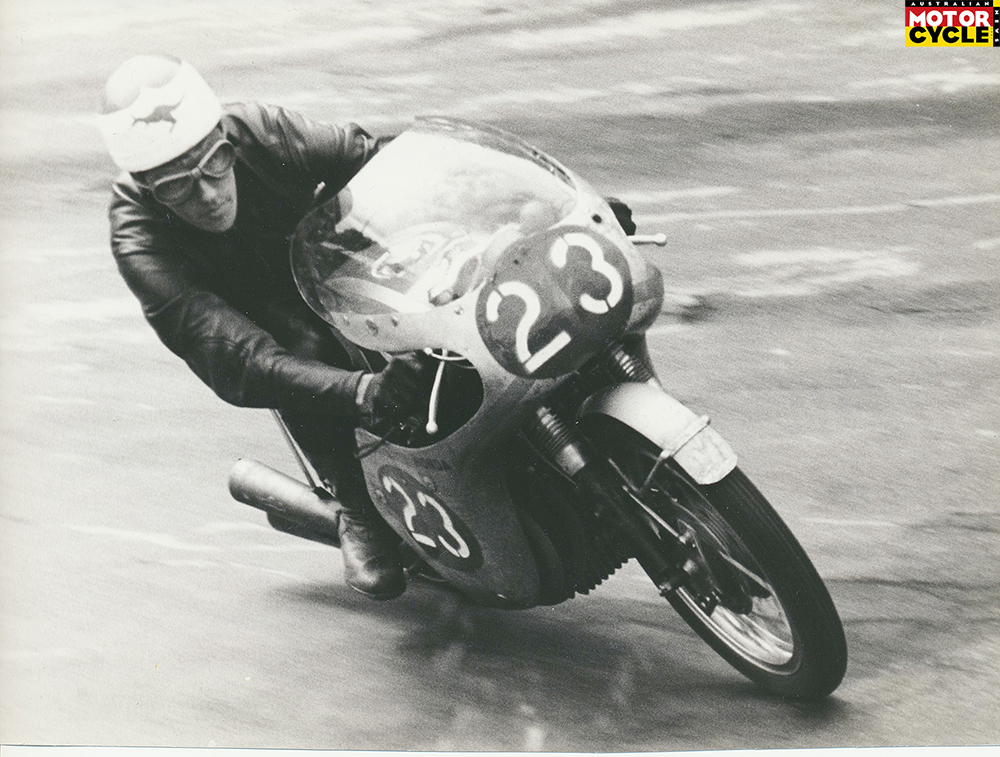

The milestones came quickly. On 23 April, Phillis riding the ‘old’ 125 etched his name in Honda history as the company’s first grand prix winner, winning on the streets of Montjuich Parc, Barcelona.

It was 17 May before Tom Phillis next wrote to his parents, from Clermont-Ferrand.

“I’m in a hotel here waiting for the French GP practice to start. There are 12 Honda men here, mechanics, riders and managers to liven things up. They were really happy last Sunday when Takahashi became the first Japanese ever to win a ‘classic’ in the 250 German GP at Hockenheim, his race speed being quicker than the previous record lap.

“I also set something of a record at the German by being the first man ever to break two Hondas in one day, so I must be at the bottom of the class just now. However, the company is most anxious for me to have some more success on the 125, following the Spanish GP result, which brightened up the camp considerably.

“It’s been busy, but ‘Blue’ (Tom’s former national service mate and now mechanic Bob Lewis) should help to lighten the load when he arrives.” Phillis won the 125 and 250 French GPs.

Early in the 1961 season, Honda boosted its European race presence by sending new-generation racers to some of its European agents, who entrusted them to Switzerland’s Luigi Taveri, Isle of Man ace Bob McIntyre and England’s rising 21-year-old star, Mike Hailwood.

Honda whitewashed the field in two classes at the 1961 IoM meeting, taking the first five places in the 125 and 250 TTs. Hailwood won both races, with Phillis third in the 125 and second in the 250.

Tom also rode the experimental twin-cylinder Norton ‘Domiracer’ to third place in the 500 TT, with the first 100mph lap recorded using a pushrod engine.

As if Phillis’s three podium finishes in a week weren’t enough, son Braddan was born during the meeting.

“Now that the frantic fortnight is over, we are on our way to the Dutch TT, taking in Mallory Park last Sunday, where I won the 250 race. The TT was not one of my luckiest races; in fact I had mechanical trouble in all four races, but kept going in all of them except the Junior (350). However, in view of the run on the Norton ‘twin’ in the 500 race, Norton Motors is being very good about my future and present repair bills. PS. Works riding is getting really hard.”

Phillis won the next 125 championship round, the Dutch TT, but lost to Taveri by a 10th of a second in Belgium. The 11-round 125 championship was developing into an intense battle, with Phillis the top-scoring Honda rider.

However, intertwined with the 1961 championship season were the stories of Ernst Degner, the MZ two-stroke racers, engineer Walter Kaaden and the German Democratic Republic that existed from 1949 to 1990.

Honda and MZ traded victories as the riders traipsed across Europe in their little vans.

A ferry trip after visiting Betty and the children in the IoM gave Phillis a chance to write to his father on 6 August.

“The world championship position is a shambles, due to a complete lack of team orders. With four more meetings to go – Ulster, Sweden, Italy and the Argentine – I’ll have to make a desperate effort to hold even one title. Even ‘Blue’ is getting nervous – the ‘big time’ atmosphere shakes him but he is really enjoying it and is a big help to me.”

Phillis’s 125 championship hopes were almost dashed when he crashed the Domiracer from second place in the Ulster 500 Grand Prix, sustaining a cracked bone in his left forearm, cuts to his hand, knee and shoulder, and concussion.

The next championship round was in three weeks, at Monza, and he had to ride, albeit below peak fitness. He finished at the rear of a Honda 125 freight train in fourth place, while Degner won. Phillis’ only consolation was fastest lap. He would end the season with fastest race lap in six of the 11 rounds.

In addition to the championship situation, Phillis was still coming to terms with the death at the Ulster GP of compatriot Ron Miles, who had been his 1959 travelling mate. On September 4, he wrote home.

“Dear all, I’m just flying back from Monza after losing my lead in the world championship to Ernst Degner. The Ulster doctors told me to take two months off after the crash there, but I had to go to this one, it was important. I felt okay in the races too, except my knees, which ain’t what they used to be. My head seems okay again except that I don’t remember going to the Ulster race day and can only remember a bit about practice.

“Ron’s death there is another matter – I remember it all clearly now, being at the hospital, phoning Bill (Miles) in Melbourne, going to the inquest, arranging the cremation… The game’s not fair – he was killed at the first corner on the first lap of practice. How is it possible?

“Mr Honda saw his first race meeting yesterday – he was very pleasant as usual, gave me a radio and told me to take it easy in the 250 race which Jim Redman won; but I think he was disappointed that I couldn’t win the 125. Unfortunately, he didn’t say anything about next year so we are still in the dark. It has been decided however that Jim and I will go to the Argentine next month.”

Events then took on the feel of a John Le Carre spy novel. The Cold War stand-off between the West and the Soviet Union gained a new symbol, with the building of the infamous Berlin Wall.

Degner created a sensation on 17 September when he defected to the West after competing in the Swedish GP, passing on MZ parts and knowledge to Suzuki. Coinciding with Degner’s defection, his wife and two sons were spirited through a Berlin check point, hidden in a secret compartment of a large American car.

On the track in Sweden, Hailwood won the 250 race to seal Honda’s first championship, while Taveri won the 125 race. Phillis was sixth with machine problems. Tom would have to wait another month to race in Argentina.

There is myth aplenty about the 1961 championship, much of it written without reference to the actual points score situation, where riders counted their best six scores from the 11 rounds. The bottom line was that Phillis needed to win or place second and have Degner not score. Degner needed to finish ahead of Phillis or for Phillis to finish no higher than third.

However, Degner’s defection meant he could no longer ride the MZ and the East German motorcycle federation wanted him banned. In England, Dr Joe Ehrlich offered Degner his EMC racer, a rotary disc valve single similar to the MZ. Degner went to London to apply his tuning knowledge to it. But the bike never reached Buenos Aires. Degner suspected sabotage by East German agents.

Phillis stayed on in South America for another two weekends, racing in Argentina and Chile, then flew home. He was feted with a civic reception at Sydney Town Hall and as the first motorcyclist featured in the ABC Sports Person of the Year.

He rode celebration laps at the Warwick Farm circuit during a major car-race meeting. One spectator recalled that when Phillis leaned into the first corner, the crowd gasped, thinking he’d fallen.

Tragically, Tom Phillis was gone within eight months of winning the championship. He crashed a new 285cc Honda four at Laurel Bank during the 1962 Isle of Man 350 TT and died in the ambulance. He was 28.

The Phillis Letters

Tom Phillis’ letters were preserved by Betty Phillis and by his parents, who both lived to their 90s. Betty and daughter Debra made them available. You can view some of Tom’s trophies

and memorabilia at tomphillis.com

Words Don Cox Photography AMCN archives & DC