1955 gave us the very first Yamaha Motorcycle: The Yamaha YA-1 Red Dragonfly

Wars drive advances in technology. By the end of WWII, guns fired more bullets in less time, tanks were heavier yet accelerated quicker, and aircraft flew faster, higher and were more manoeuvrable. But when wars end, armaments factories – especially those making fighter aircraft – have to find new things to manufacture.

Japan made motorcycles before the war, although there were probably only a handful of manufacturers including Meguro Manufacturing (who made the 500cc Meguro), Mizuho Motors (250 and 350cc Cabton), Miyata Manufacturing (Ashai AA, Japan’s first mass-produced motorcycle), and Sankyo (Rikuo, a Harley clone made under licence). Except for the Ashai AA, they were only made in small numbers, but with the end of hostilities motorcycle production was about to really take off. And it was those involved with fighter aircraft that led the way.

Nakajima Aircraft Company made Hayabusa fighters and Kate torpedo bombers, but in 1946 it became New Fuji Industries and began production of the Rabbit automatic transmission scooter in Tokyo. Later that same year, industrial giant Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, famous for its A6M Zero fighter plane, started making the 175cc Silver Pigeon scooter in a corner of its works at Nagoya.

Soichiro Honda, who had developed automated machinery to churn out piston rings for fighters and bombers produced by Nakajima, built his A-Type motorcycle engine in 1947. And Kawasaki Aircraft Co, who manufactured the ground-attack Dragon Slayer and the Daimler- Benz V12-powered Flying Swallow, made its first motorcycle engine, a 150cc OHV four-stroke single, in 1949. Suzuki – who made weaving looms before the war and then aircraft sights, machine guns, and high-explosive shells for the Imperial Japanese Army – also jumped on the motorcycle bandwagon in 1952 with two-stroke tiddlers for the masses.

Japan built fewer than 2500 motorcycles in 1939, but by the end of 1953 production had soared to over 166,000 thanks in part to new rules that allowed riders as young as 14 to get a licence without first taking a test – as long as the capacity was less than 91cc for a four-stroke and 61cc for a two-stroke. By early 1954 Showa Aircraft had taken over Rikuo and started making copies of the 250cc BMW R20, while Marusho produced the Lilac, a 175cc version. Japanese magazine Motor Fan reported that there were between 50 and 100 motorcycle manufacturers, while American magazine Buzz pinned it down to 49 motorcycle factories and another 70 making cyclemotors. Of course not all were industrial giants – many were described as “factories in the home” or backyard builders. There was even a powerful trade association comprising 28 companies in Hamamatsu, headed by Suzuki Shunzo, the boss of Suzuki Motor Company.

When Captain Soar of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers visited the factories in Japan, he was very impressed: “Down-time is kept to a minimum, not necessarily by workshop organisation, although this is an essential factor, but because it seems to be a national characteristic for them to keep working all the time there is a job to be done. If a specification for a job is laid down, then the individual can be left to do it.”

One year after Captain Soar’s visit another manufacturer was about to burst onto the motorcycle scene. Founded by Torakusu Yamaha, Nippon Gakki Seizo Kabushiki Kaisha (Japan Musical Instrument Manufacturing Co) started building pianos in 1900, but in 1921 they branched out into making wooden propellers for aircraft. After Japan invaded China there was even more demand for propellers, so Nippon Gakki stopped piano production – although they continued making harmonicas and xylophones – and began casting, grinding and machining alloy propellers at a rate of one a week. When WWII started they simply couldn’t make propellers fast enough because their methods were too labour intensive. That’s when Soichiro Honda was called in to help out. In 1943 he designed an automatic high-speed milling machine that could simultaneously mill the surfaces of two variable pitch props for a Zero in only 30 minutes. At its height, Nippon Gakki employed 10,000 people in factories throughout the country, and was also making aircraft fuel tanks and wings.

After the war Nippon Gakki once again began making harmonicas and in January 1947 the company shipped 24,000 to America. But they also had a pool of talented engineers who could use the machinery and casting equipment designed for making aircraft parts. Although he knew they were late joining the party, company president Genichi Kawakami decided to make motorcycles; however, he didn’t want to go down the scooter route dominated by Fuji and Mitsubishi. And he didn’t want to make motorised bicycles either. He was going to use his industrial muscle to make a better motorcycle in a purpose-built factory, so he sent his best engineers and designers on a tour of Japan’s top manufacturers. They reported back that, although there were some good products, European motorcycles were better. Kawakami-san duly sent them on a trip to Europe, and they finally found what they were looking for in Germany.

The most advanced two-stroke engines available for road-going motorcycles were built in Zschopau by DKW, once the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer. That was now in the Russian sector, so DKW opened a new factory on the Danube at Ingolstadt and began making the three-speed unit construction RT125 again in 1949. Because of war reparations this was a patent-free design and the three-speed Deek was copied by Harley-Davidson, who made the Hummer, and Moto Morini, who made the 125 Tourismo. Perhaps to disguise its German origins BSA produced a mirror image of the engine with the gearchange on the right and called it the Bantam. Now the RT125 would become the basis for Nippon Gakki’s first motorcycle.

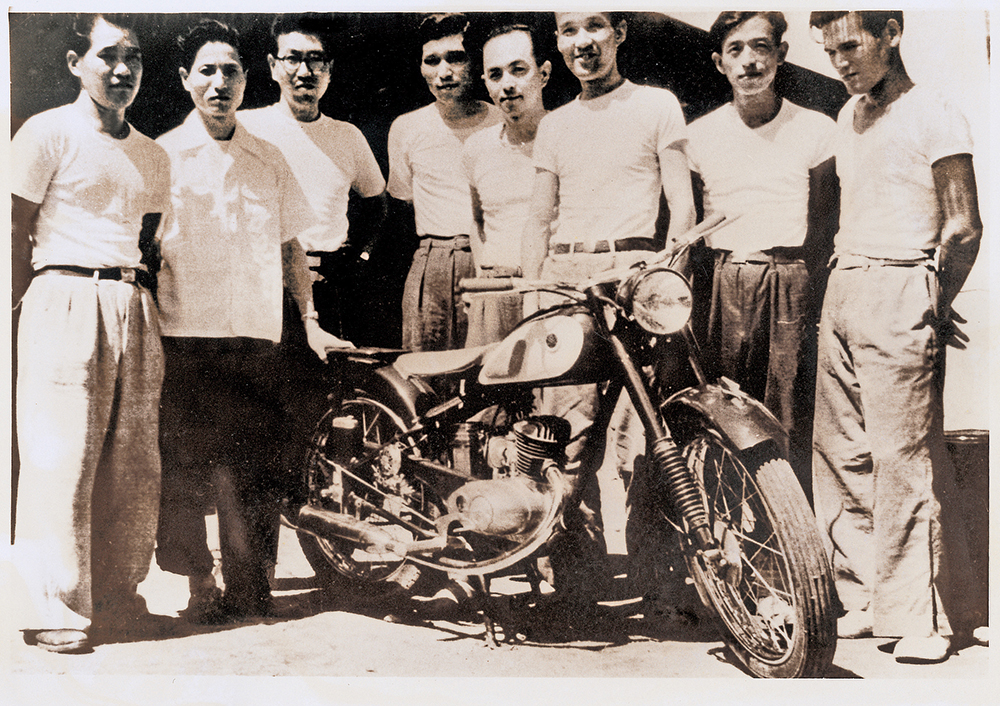

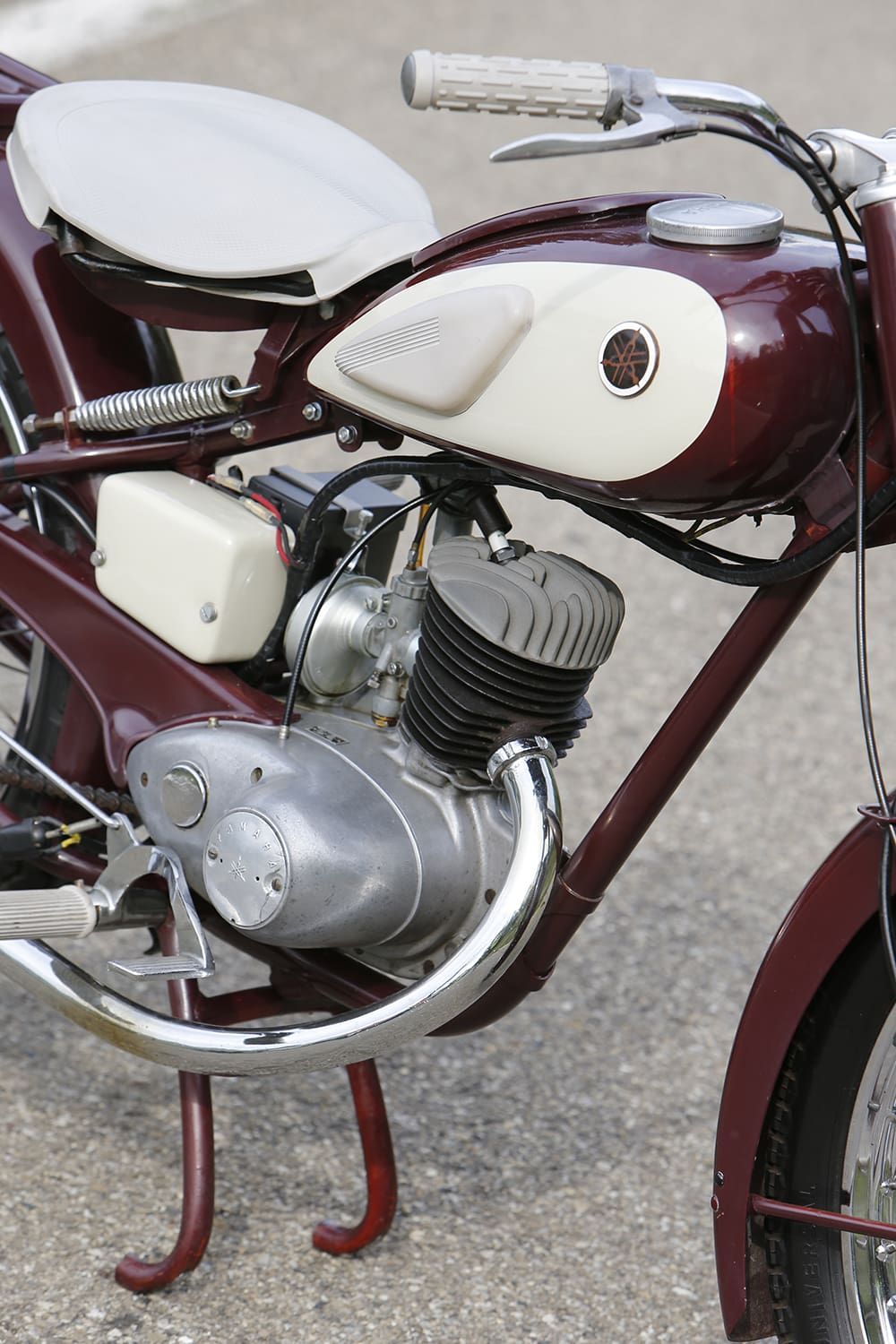

Development engineers began work in October 1953 and the prototype Yamaha YA-1 was ready for testing the following August. Although it shared the same 52 x 58mm bore and stroke as the DKW this was no simple copy. For a start, there was an extra ratio in the gearbox and there was a geared primary drive instead of the Deek’s chain. And while most motorcycles could only be kickstarted with the gearbox in neutral and the clutch engaged, this Japanese design used a primary kick-starting system. The large primary driven gear was turned by means of a kick idling gear and a kick pinion, so the engine could be started in any gear as long as the clutch was released. And it was possible to shift directly in neutral with just a half-stroke of the lever from any gear.

There was a telescopic fork and plunger suspension at the rear, but whereas most plungers use grease to lubricate the sliding parts the Japanese employed an oil bath. In a nod to the company’s musical instrument heritage the enamelled badges on each side of the 9.5L petrol tank featured three tuning forks, and there was also a stylised brass tuning fork mounted on the front mudguard. The tuning fork device and the chestnut red and cream finish were the work of Professor Iwataro Koike’s team at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Members of his group would later go on to design the iconic Kikkoman soy sauce bottle.

After the bike passed a tough 10,000km endurance test, Kawakami-san gave the go-ahead for production to begin in January 1955. Named in honour of Nippon Gakki’s founder, the first Yamaha motorcycles began rolling out of the new Hamana factory in February at a rate of 200 a month. Because of its slender shape and stylish paint job, motorcycle enthusiasts were soon calling the Yamaha YA-1 the Aka-tombo – Red Dragonfly. On 1 July 1955 the motorcycle business was split from Nippon Gakki to become Yamaha Motor Company.

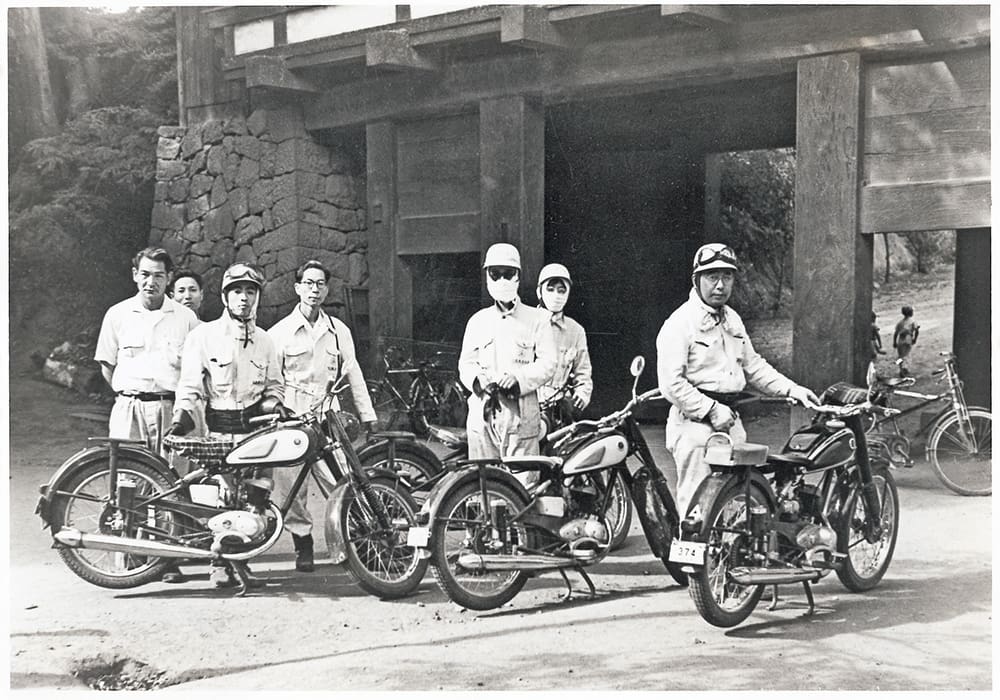

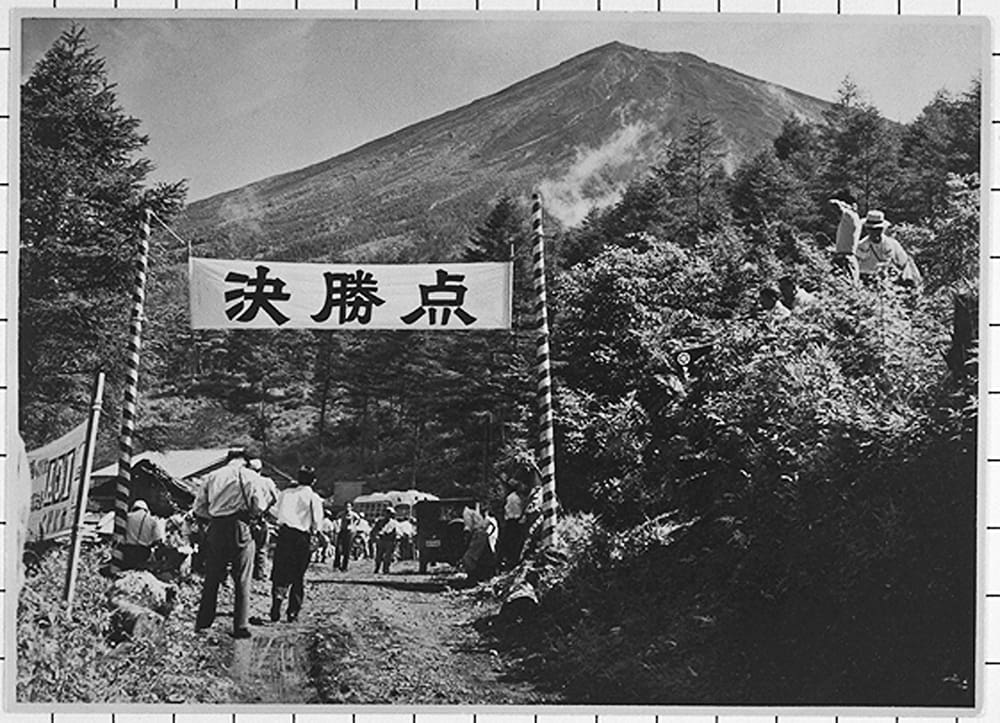

Then it was time to show just how good the Red Dragonfly was by entering the third Mount Fuji Ascent Race. The dirt road was more like a motocross circuit than a racetrack. Riders climbed from the Asama shrine in Fujinomiya to the finish line one-fifth the way up to the 3776m summit of the volcano. Open to production models only, it was the most prestigious race in Japan.

The Yamaha YA-1 produced a respectable 5.5hp (4.1kW)at 5000rpm before Yamaha’s technicians started working on it. A silencer from the latest DKW RT125 added half a pony so they made their own version, and high-octane fuel and colder spark plugs also boosted performance. Ten riders were entered for the Mount Fuji ascent, and they spent several days practising on the 24.2km course until they could do it blindfolded.

On 10 July the Yamaha team arrived. Then, while other teams looked on in bewilderment, the technicians whipped the covers off a mobile dynamometer. Each Yamaha YA-1 was run up and the ignition and carburetion tweaked for maximum performance for the altitude and atmospheric conditions. Whether this really made a difference to engine performance is debatable, but the show probably help psych out the opposition.

When riders set off in pairs at 30-second intervals for the time-trial race it was clear that the Red Dragons were really buzzing. All that practice had paid off and Teruo Okada won the 125cc class with a time of 29 minutes 7 seconds. He crossed the finish line ahead of a Honda Benly, with five more Yamaha riders among the top 10 finishers.

The first Asama Highlands Race – officially called the Japan Motorcycle Endurance Road Race – took place the following November. This four-lapper was for factory bikes, and started at the bottom of Mount Asama with the steep and winding 19.2km dirt track running up to a field on the Asama Ranch, before spinning around in a cloud of dust and returning to the bottom. The course was made more imposing by the sight of the volcano, still smoking after an eruption the previous winter. Soichiro Honda and his team were no match for the Yamaha YA-1 Red Dragonflies and Yamaha claimed the first four places.

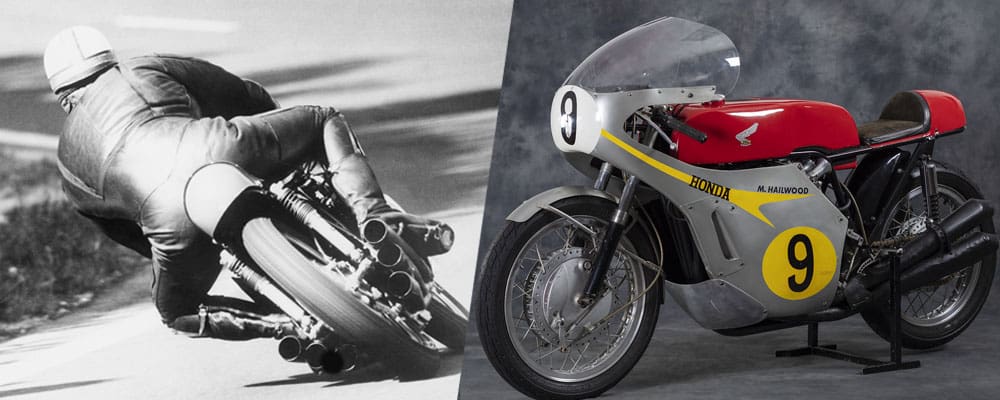

With two major victories and masses of publicity the Yamaha YA-1 Red Dragonfly flew out of the showrooms. From a standing start Yamaha went on to build 2272 in 1955, and when production finished at the end of 1957, that number had grown to 11,088. By 1966 Yamaha was racing a 125cc V4 two-stroke and churning out over 250,000 motorcycles a year.

The tuning fork was humming.