Forty years ago, global warming wasn’t a dirty phrase. Thus the sweltering summer of 1976 – which kept setting new records for warmth and days of sunshine – was something just to be enjoyed in Britain and all over Europe.

Few can have enjoyed it quite as much as Barry Sheene.

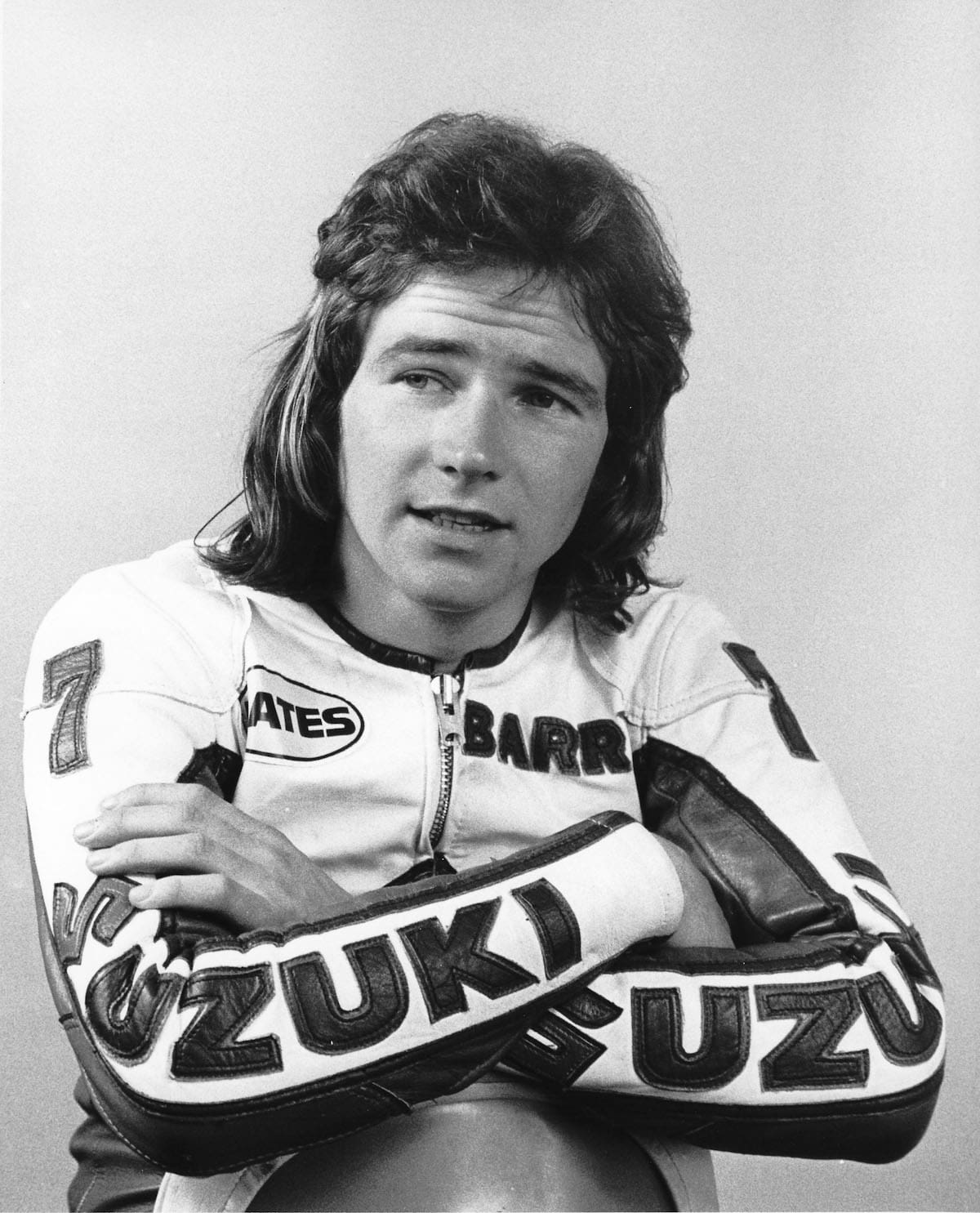

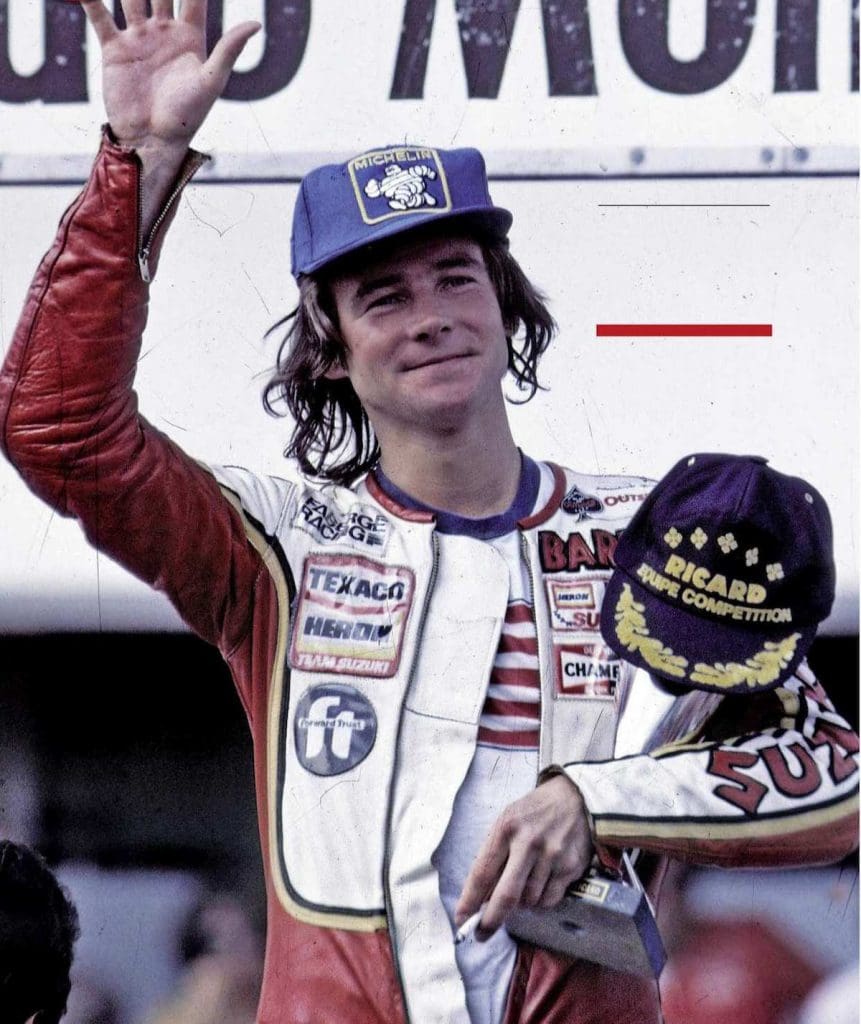

It was the year that a legend was born, as this cheeky charismatic cockney took grand prix racing by storm. He would win just one more championship, in 1977, but his era would last much longer. As Barry Coleman, biographer of Sheene’s nemesis Kenny Roberts, opined: “Sheene was still World Champion long after he’d stopped winning.”

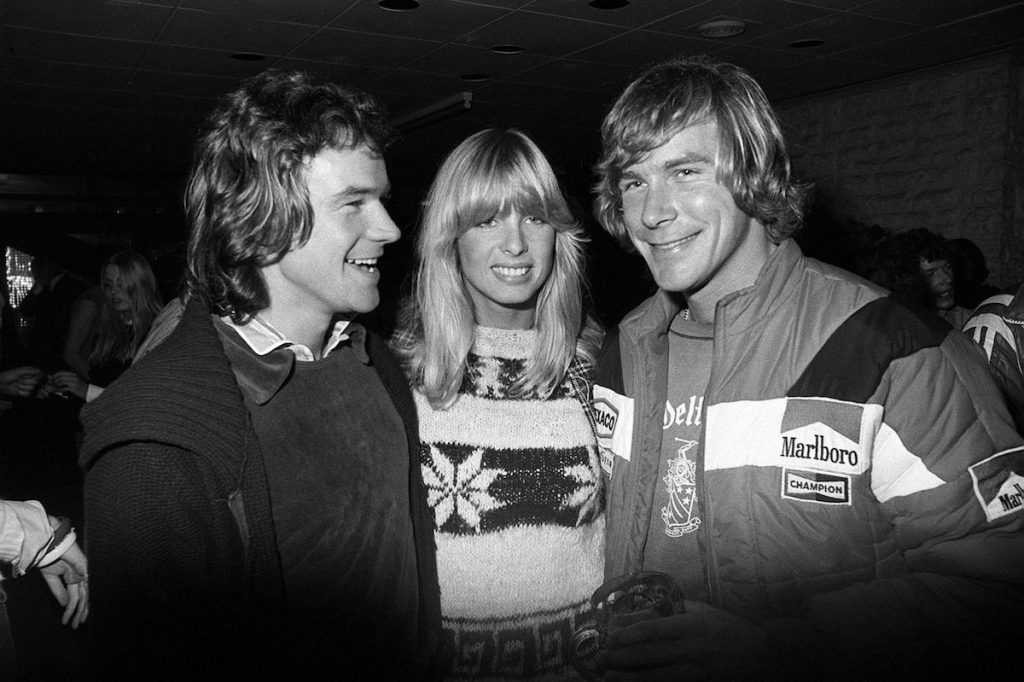

The year was pivotal in many ways, and Sheene was a telling influence. Thanks to his quick wit and knowing charm, his jaunty working-class manner and an unerring instinct for self-promotion, he was making bike racing sexy. At the same time, another playboy from the opposite end of the social scale was doing the same thing in Formula 1. James Hunt won the title that year, by which time the two were firm friends and instantly recognisable in all the fashionable clubs and nightspots of swinging London – shaking their locks to Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody and The Funky Gibbon.

For motorcycle grand prix racing, 1976 marked the final turning point in the battle between traditional four-strokes and the upstart two-strokes. It was the last year an MV Agusta raced, on a grid now the full-time property of Japanese two-strokes. Giacomo Agostini finished a well-beaten seventh overall. Ago did close his and the MV’s careers however with a win in the final round at the old Nürburgring – a race that Sheene did not bother to attend.

It was the year that Suzuki’s seminal square-four RG500 came of age. All six riders in front of Agostini rode RG500s. The bike would win the constructors’ title from 1976 to 1982.

And Sheene’s ascendancy marked an acceleration of a hitherto rather half-hearted move towards full commercialisation of racing. Ever the sharp operator, fully aware of the commercial value of his easy, natural popularity, Sheene ramped up his personal wealth to a hitherto unprecedented degree. Other riders, especially in years to come, would benefit from the massive hike in the scale of fees led by this one-man army.

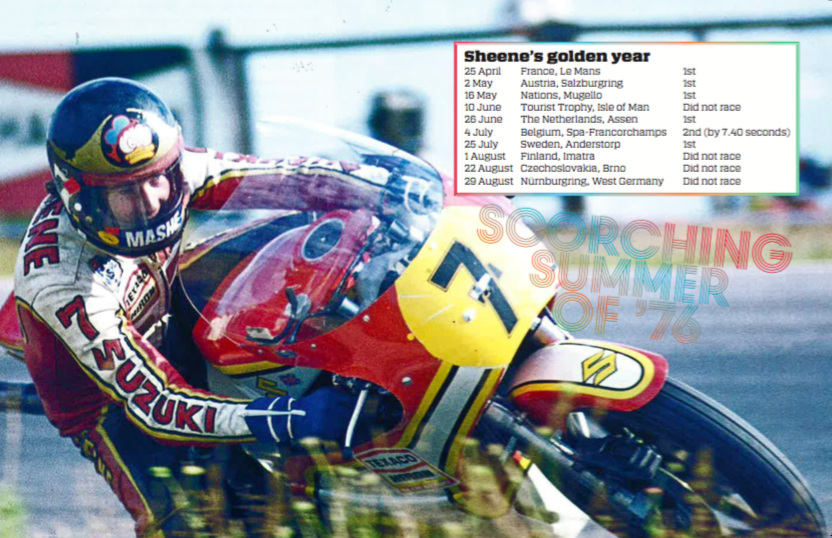

From now on, fairings and riders’ leathers would, like Barry’s, be adorned with commercial logos. On a larger scale, in addition to the traditional technical sponsors like Texaco and Castrol, Sheene virtually single-handedly brought in money from previously undreamed of sources, as diverse as Mashe jeans and perfume giants Faberge (“Nothing,” said Barry on the TV ads, “beats the great smell of Brut.”)

I got to know Barry during these years: I was editing the monthly SuperBike magazine at the time. I found him a tricky customer. Especially after we published a satirical piece mocking the adulation heaped on his every utterance by the rest of a British media slavering at his loins. It was meant to mock the journalists and the magazines; Barry took it personally.

He got over it, though, more or less. Though he never did forgive me for writing an unauthorised biography for an independent publisher a few years later. To him, and never mind legitimate reporting, anybody mentioning his name to make money was “a parasite”. The same epithet he applied to team members he thought were overpaid or supernumerary. (A saving grace: he told me he preferred the warts-and-all biography to a simultaneous official hagiography. Or was he just saying that, in his usual natural way of charming everybody he met?)

Barry’s force and power as a racer was no less than that of his personality. He’d risen rapidly through the domestic ranks on a tide of talent backed by privilege – his father Frank was a well-known racing tuner and entrant, and UK importer of Bultaco motorcycles. Relentless in his quest for publicity, he backed it up with wins. And conspicuous personal courage.

By 1976 he had already achieved unprecedented fame beyond just racing by the uncomfortable means of a ghastly crash. A tyre delamination at more than 280km/h on the Daytona banking at the start of 1975 left him with a comprehensive IC-ward full of injuries ranging from a badly broken femur, wrist and several ribs to the loss of enough skin, as he put it, “to cover a sofa”.

“If I’d been a horse, they would have shot me,” was another smart-aleck remark. The gallows humour was the backdrop to his own determined fight back to race fitness.

As it was Barry, these plucky remarks achieved the widest distribution – it just so happened that a TV film-maker was making a documentary on this new star of racing. The accident, its aftermath, and even the surgery hammering a pin into the broken thighbone, it was all on film and soon broadcast nationally.

It’s a good thing to be heroically brave. Even better when the whole world knows about it. In this way, even the highbrow daily papers followed new media star Barry’s determined recovery, and his return to the racetracks only seven weeks later.

At the same time, Suzuki was building a rocket-ship.

In fact, by 1976 the four-stroke premier-class bastion had already been breached. The first two-stroke 500 champion would undoubtedly have been Finnish racing genius Jarno Saarinen in 1973. Riding Yamaha’s new in-line four, he had easily won two of the first three races, but lost his life in a notorious multiple pile-up in the 250 race at round three at Monza.

Yamaha withdrew out of respect, and MV Agusta won the title, in the hands of multi-champion Agostini’s highly intrusive teammate Phil Read. Ago would storm off to join Yamaha, but Read won again in 1974 as the Italian legend came to terms with the very different riding style required for his first two-stroke. Then in 1975, Ago took four wins to Read’s two, and won the first two-stroke title by eight points. But there was a new name on the winner’s listing with the same number of wins as his compatriot Read: Barry Sheene (Suzuki).

Yamaha’s 500 was, in retrospect, rather simplistic: a pair of 250 twins mounted side by side – an in-line four, although with two crankshafts, joined at the central power take-off. It was rather wide, and used piston-port induction, making it rather tetchy with a narrower power band.

Suzuki borrowed an idea from their own past in the smaller classes, copying a 125 design. The engine was also a pair of 250 twins mounted across the frame, but one behind (and slightly above) the other rather than side by side. (In fact, each cylinder had its own crankshaft, making it effectively a quadrangle of 125cc singles.)

The engine design was compact, and offered another key advantage: each cylinder was accessible to a side-mounted carburettor feeding through a rotary disc valve, making it a more precise and powerful system. The RG500 XR14, the first prototype, was the world’s first genuine 100-horsepower grand prix bike.

Sheene came back from his first tests in 1974 with wide eyes. Later he explained: “It was very fast, and a bit lethal. The prototype was more powerful than the bike I won the title on two years later. It had the power band of a 125.”

Paul Smart was also at the tests, and signed up alongside Sheene and Jack Findlay for the 1974 season. That first version was, he told me recently, terribly unreliable. “Every part of it broke, to start with … everything. The big gears joining the crankshafts, piston seizures … I remember the first race we went to, the grand prix at Clermont Ferrand. Mine did 300 yards – first, second, third, locked solid, with all the pack behind me. And Barry completed the race. [In fact he finished second, just five seconds behind Read’s MV.] Mine seized up every time I got on – never finished a race for the first six or seven races.”

Sheene finished second, third and fourth among many breakdowns; but an improving bike for 1975 brought Sheene’s and the bike’s first 500 GP win at Assen, adjudged victor by a wheel after he and Agostini recorded the same time. A second came in Sweden, beating Read’s MV by miles.

The stage was set for the summer of ‘76.

Yamaha had withdrawn direct factory support, Suzuki wanted to do the same, but the Sheene factor meant British importers Heron Suzuki persuaded a slight policy change. They agreed to supply factory-backed bikes for a British-run team. They were only slightly faster than the production RG500s selling rapidly to privateer riders.

The field was clear for a Suzuki takeover. But which of the many RG500 riders would be the best? There were any number of private Suzukis, including one for Phil Read, as well as rising young Italian Marco Lucchinelli, the well-regarded French rider Michel Rougerie and new American Pat Hennen.

Sheene’s UK team included dad Frank and old-pal mechanic Don Mackay. They would contest not only the GPs, but also Daytona in the USA, the UK-based MCN Superbike and Shellsport 500 series, and selected rounds of the F750 series.

There were ten GPs that year, although only the best six results counted to the final points. Barry and the Texaco Suzukis were able to pick and choose races. In this way, Barry – always a staunch opponent on safety grounds – shunned the Isle of Man TT, in its last year as a championship round.

The grand prix campaign started in France, cold and windy at Le Mans. Pole qualifier Barry’s leg injuries were aching, and the uphill push start worried him. He requested a pusher, and to start from the back, but was denied. Slow away, he forged through to the front, to catch and ultimately pass Cecotto on a lone ex-factory Yamaha.

Sheene was on pole again at Austria, and took another clear win as Cecotto crashed trying to keep up, Lucchinelli was a distant second, Read third.

The summer and the pace were hotting up. Race three was at the then-new track of Mugello, and the layout – one of the most popular today – was, to Sheene, “uninteresting and dangerous”. His third win in a row was a classic, tooth and nail with Read all the way.

Sheene did it all again at Assen, pole and fastest lap as he claimed yet another successive win, his fourth. Sheene was notably the fittest finisher on a day when heat-stroke nearly claimed the life of one sidecar competitor, and overcame several others; Pat Hennen’s Suzuki was an impressive second.

The next race, one week later in the forests of Spa, was pivotal for many reasons. Victory for Barry would have tied up the title with four rounds remaining; instead he came second. The axis was within the team, and an increasingly bitter rivalry with pit companion John Williams came to a head. Williams was determined to prove he could beat Suzuki’s big star. He meant to lead until the last lap, then slow before the line to make it obvious he was letting Barry win. But Barry wasn’t there. He was limping home with fuel vaporisation in the heat. ‘Willy’ waited and waited, before coasting round the final hairpin as reluctant winner by almost 10 seconds.

Barry had to do one more race, in Sweden, and he need finish no better than third to be sure of his first world championship. That is not, however, the style of a champion – a view shared by Valentino Rossi. Barry did it with another fine win, shaking off all challengers to finish streets ahead. It was still only July, with the full heat of the summer still to come. Hunt would have to wait until the end of October before adding the Formula 1 crown to Britain’s tally.

Sheene won a dominant title the next year, but in 1978 came another pivotal change. He would be the last British champion in a class which they had once dominated, for Kenny Roberts arrived and took over, and the era of the tail-sliding Americans had begun.

Sheene himself survived another major crash at Silverstone in 1982, and retired at the end of 1984 with a tally of 19 wins. He moved to Australia where a warmer climate was kinder to the extensive metalwork in his legs, and died of cancer in 2003, aged 52.

Hunt, his playmate in the priapic days of their greatest pomp, had died 10 years earlier of a heart attack, aged just 45.

The last word to Roberts, who ended Sheene’s reign. “If Barry had stayed with Suzuki, he would definitely have won more championships.”

STORY MICHAEL SCOTT